Vanity and Chemo: Cancer Can't Take My Eyebrows

I expect there are very few people who realize how vain I am. I mention it sometimes — literally, I tell people, “I’m really, really vain” — but for the most part this gets minimal to no reaction. Some people counter with “No, you’re not,” which brings me up short. How would they know?

Despite being fairly self-aware where vanity is concerned, I was completely unprepared for my reaction to learning that I’d likely lose my hair, eyebrows, and eyelashes while undergoing treatment for Hodgkin’s lymphoma. For days, I kept stopping to look in the mirror. I’d hold my fingers over my eyebrows and try to imagine my face without them. I was going to look like an alien.

I have thick, wiry, black brows and lashes. I was in middle school during the over-plucked late ’90s, when it was pretty universally agreed upon that my bushy eyebrows constituted a “problem area.” I used to do the same thing at age 12 or 13: stand in front of the bathroom mirror and hold a finger over most of my eyebrows, imagining how much better I’d look if I could manage to pluck them into a thin, even line (I couldn’t). Back then, I would’ve secretly looked forward to a treatment that cost me my eyebrows, the same way some sick women look forward to losing weight. But times changed, thick brows are back in fashion, I’ve had another decade and a half to master basic grooming and get used to my face with its natural features, and oh hell, I am not losing my eyebrows.

As I started to contemplate the hair loss, a strange thing happened. I became much more beautiful. I thought I’d been vain before, but over the course of a few days in late August, I reinvented the concept. Almond eyes, long lashes, defined brows. And not just my own. Everywhere I went, I was completely overwhelmed by beauty. I stared at strangers on the subway long past their first, second, and even eighth what are you looking at looks. It’s not particularly acceptable to walk up to random people, tell them they’re beautiful, and burst into tears, so for the most part I just stuck to staring. I stopped wearing makeup. I stopped appreciating other people’s makeup. Natural features were miraculous enough on their own — hell, they were almost too much, sensory overload. I even stopped brushing my hair. It was thick and brown and a little curly when I woke up from sleep — perfect, right? (Wrong.)

The effect faded. I went back to wearing light eyeliner and straightening my bangs, and I stopped staring so much. I also embarked on a complete freak out about losing my brows and lashes. I scoured message boards looking for an out, but it didn’t sound like there was any hope: on ABDV, the chemotherapy used to treat Hodgkins, almost everyone loses their body hair.

Then, somewhere in the depths of my internet research on chemo and eyebrows, I came across the technique of permanent makeup, which these days is really semi-permanent makeup, or sort-of-temporary tattooing. Some people, it turns out, get their eyebrows tattooed on before chemo. The effect can be a little weird though, like someone drew them on with a sharpie.

After some more research, I discovered a process called microblading. Instead of one continuous eyebrow line, an aesthetician inks on individual strokes, mimicking the look of real hairs. It’s stupidly expensive, but the results look incredible, and having cancer gives you license to do stupidly expensive things for the sake of your vanity. Also, my incredible parents ended up making it a gift — I think they were a little amazed that there was actually something they could buy that would make me feel less shitty and scared about having cancer.

Since tattooing poses a risk of infection, cancer patients are supposed to get their oncologist’s permission before getting semi-permanent makeup. I, however, had only just gotten my official diagnosis and wouldn’t even be meeting my oncologist for another ten days. No one could tell me no. Perfect timing. Or so I thought.

As it turned out, the semi-permanent makeup industry is not set up to help cancer patients out during the brief window between diagnosis and starting chemo. Most salons in New York book microblading months in advance, and were therefore impervious to my not-at-all-subtle attempts to play the cancer card.

Then I found Annie. Her Yelp reviews were all 5 stars. Her prices were slightly less than half of those at most New York salons. And when I called, her assistant said she could fit me in that day at 5:30. Booking that appointment was my first concrete accomplishment since getting diagnosed with cancer the day before. It made me feel bizarrely, disproportionately triumphant, like I’d started crossing things off a to-do list, at the end of which was “beat cancer.”

Annie is an artist, and a perfectionist. When she first saw me she shook her head and said, “But you already have such thick eyebrows!” When I explained that they were probably going to fall out during chemotherapy, she got very quiet and had me sit down while she examined them. Then she came back with her verdict: She couldn’t do the microblading, because my hairs were too thick and plentiful to work around. What she could do was the “powder-effect” tattoo — or, as I called it above, drawing the eyebrows on with a sharpie.

No, no, no. There was no way I was resigning myself to a choice between sharpie eyebrows and no eyebrows. Not when I was so close.

I told her I didn’t mind if the eyebrows didn’t turn out perfect — I could always fill them in with makeup before I went out. But I wanted to go to sleep and wake up with something resembling my normal features on my face.

Finally she nodded. She told me that her father had passed away the year before from cancer. He’d also undergone chemo, and had lost his hair. She would try.

I spent the next three hours lying face-up on a table with soft ambient music playing and a needle scratching lines in between my eyebrow hairs. People keep asking me if it hurt. Yes, it hurt. Numbing cream is a joke. Or maybe I have sensitive skin.

But I’m going to let the oncologist pump poison into my veins, in exchange for which I will likely lose my hair and kill my cancer. What’s 3 hours of getting my eyebrows scratched up in exchange for not looking like an alien while I’m throwing up in the toilet?

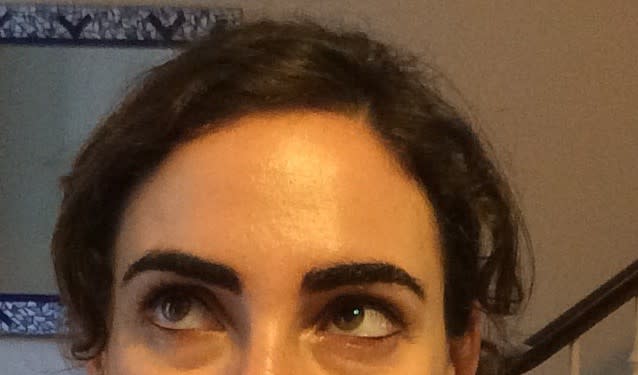

When she finished, Annie showed me the results in a mirror. I was the first person she’d ever worked on pre-chemo, with thick eyebrows firmly in place. And she managed a fantastic job:

She teared up before I left and told me that she’d cried that day on the subway, missing her father. “I’m so glad I got to do this for you,” she said.

I’m so glad too, and I’m also a little less terrified. It’s like I have armor now — semi-permanent makeup armor. Thank you, Annie.