10 Must-Read Stories for Escaping Reality Right Now

We’re in a moment in time where if we’re lucky we’ve nothing but time on our hands—otherwise nobody would be baking sourdough bread for the first time or going half-blind trying to assemble that 4,000-piece puzzle of Monet’s waterlilies. We can document our boredom all we want—here’s me in a mask, me having Zoom cocktails, me baking sourdough bread for the first time—but once that’s exhausted, we’re still hungry for substance. We yearn to feed our head and our souls.

And let’s face it, we’re hungry for that relief, distraction, and inspiration in equal doses. That in mind, we at Esquire just happen to be sitting on 87 years of one of the richest cultural archives in existence. If nothing else, the history of Esquire is crammed with great storytelling—from longform investigative journalism to fiction by some of our finest novelists—and now, more than ever, we need stories. To help entertain us and make us think—and in our case, make us feel.

So now is the perfect moment to take that deep-dive and lose yourself in a past that enriches and informs the present. Here are ten very different kinds of stories—from novellas, to true crime to celebrity profiles, by some of the finest writing talent this country has ever produced—I suggest digging into.

“The Golden Age: Time Past”

by Ralph Ellison.

Anyway you look at it, 1959 was a killer year in Jazz: Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue, John Coletrane’s Giant Steps, and Dave Brubeck’s Time Out are just three of the most famous records to drop that year. They were colossal, influential records decades before they became the ubiquitous soundtrack at Starbucks. And yet for Ralph Ellison, author of the Invisible Man, Jazz was dead by ’59, the scene full of pretenders and wannabes. In his wistful reminiscence of Minton’s Playhouse, the Harlem nightspot where, in the early 1940s, radical innovators like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie created the modern language of jazz, Ellison offers a classic old school vs. new school lament.

Minton’s was to jazz what CBGB was to punk rock, a rendezvous for musicians where “most of the masters of jazz came either to observe or to participate and be influenced and listen to their own discoveries transformed; and the aspiring stars sought to win their approval.” Ellison is wary of the tricks nostalgia plays on us but he evokes Minton’s with the clarity and grace that informed his great novel.

“Breakfast at Tiffany’s”

by Truman Capote.

Few 20th century American writers were as famous as Truman Capote. He was an original—first-rate writer, unforgettable personality, bona fide celebrity, tragic flop—and, incidentally, the first openly gay man to appear on Esquire’s cover. Norman Mailer called him “The most perfect writer of my generation,” after reading Capote’s stinging 1958 novella, “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” originally published in Esquire. “He writes the best sentences word for word, rhythm upon rhythm. I would not have changed two words in Breakfast at Tiffany’s.”

If you’re looking for something juicy to sink your teeth into, this 26,000-word story is the gift that keeps giving. Few short story characters become pop culture icons but the heroine of this story, Holly Golightly, became a household name. Never mind the watered-down movie version, which was never much good and has aged poorly (especially Mickey Rooney’s cringe-worthy performance as the landlord) but the original story is sharp and irresistible, Capote in his prime.

“Mick Jagger, I Love You”

by Helen Lawrenson.

From the days when writers could write about their subjects without fear of reprisal. Helen Lawrenson was one of the Esquire’s most famous writers; her 1936 farce “Latins Are Lousy Lovers” caused a scandal. She was Eve Babitz before Eve Babitz. If she didn’t like a subject, she didn’t care about offending them—or their publicists. Lawrenson was approaching 70 in 1968 when she visited Mick Jagger, then considered the Devil to any God-fearing adult. She expected to hate him but after visiting with Jagger in the studio, where the Stones were recording Beggar’s Banquet, and then on the set of Performance, his film debut, Lawrenson was surprised. He was smart—clearly the brains of the operation—and charming.

“The people who detest him are those for whom he crystallizes their uneasiness over today’s iconoclastic youth and the increasing erosion of orthodox mythology. What makes him so infuriatingly insufferable to them is that he seems to know he’s right—and they’re wrong. Whatever they think of him is, however, irrelevant both to him and to them. He is the present and the future. They are the past.”

“Parker’s Back”

by Flannery O’Connor.

Tommy Lee Jones once said that if he were handing out Flannery O’Connor stories as Christmas gifts he’d give out “A Good Man is Hard to Find”—one of her most famous tales—or “Parker’s Back.” There is a Coen brothers connection at work here and not just because Jones starred in their Oscar-winning drama No Country For Old Men. It’s because as you read “Parker’s Back” it’s hard not to detect the sadistic, deadpan, and bleakly hilarious Coen brother’s sensibility. (Why haven’t they done an O’Connor adaptation yet?) People don’t learn things in her stories, they don’t change, they only march ahead stubbornly to their fate. And it usually ain’t a happy one. Decades before tattoos became mainstream, this story will send chills down your spine but also keep you chuckling.

“Dead Ringers”

by Ron Rosenbaum and Susan Edmiston

Who doesn’t love some true crime, particularly when it is as bizarre as the case of the Cyril and Marcus Stewart, identical twins, and prominent Manhattan gynecologists whose bodies were found rotting away in Cyril’s apartment weeks after they’d died? One twin no longer had a face when they were discovered, his face had decomposed. But their grizzly ending is just the beginning of the weirdness—the Stewart twins not only masqueraded as one another, their practice was full of strange and dangerous decisions. “They called themselves infertility specialists, but in the eyes of many of their grateful patients they were nothing less than fertility gods.” But that soon changed. And the Marcus’ specially-made tools—which are nightmarishly evoked in David Cronenberg’s 1988 movie of the same name (streaming now on Amazon Prime)—are just the most shocking part of the scandal that was the talk of New York in the summer of 1975. Ron Rosenbaum—with the help of Susan Edmiston—is one of the great chroniclers of the evil that lurks just beneath the surface of civilized society, and this story will keep your heart racing throughout.

“The Life and Death of a Comic Genius”

by Robert Sam Anson

A few years back, Will Forte played Dough Kenney in the Netflix movie, A Futile and Stupid Gesture. Kenney was one of the masterminds of post-collegiate, subversive ’70s comedy, first as co-founder of National Lampoon magazine and then the co-writer of Animal House and Caddyshack. Those two movies alone made Kenney rich—at the time Animal House was the highest grossing comedy of all-time—and they helped set the stage for decades of comedy to follow. Kenney was a huge talent, a charismatic if deeply troubled guy who died at age of 33 when he fell, or jumped, off a cliff in Hawaii, depending on who is telling the story.

His vibrant but truncated life and times is documented with flair by Robert Sam Anson this 1981 feature. “Who was Doug Kenney?” his friend Chris Miller asked after they had brought his body home. “Doug was Holden Caulfield, the Catcher in the Rye.” As Anson tells it, “This is his story. It is not funny.”

“The Ballad of Johnny France”

by Richard Ben Cramer.

Another one for you true crime buffs—here’s a yarn for you. All about the Montana sheriff who searches for a woman kidnapped and held prisoner by two mountain men. Kari Swenson was a world-class biathlete in training, running a trail near the Big Sky resort when two men jumped out of the woods, grabbed her and chained her to a tree. They were looking for a wife. Johnny France was the sheriff who understood these men, knew the wilderness, and was the best chance to find Swenson.

Cramer is one of our favorite contributors—and wrote perhaps the best sports profile ever written—and this is one of his most unheralded pieces. Cramer once described his technique: “I’m the guy on the barstool who is telling the story. And they’re in the armchair listening. As long as I can keep them from remembering that they’ve got to go home tonight, we’re good.”

Mission accomplished.

“Jim Morrison is Dead and Living in Hollywood”

by Eve Babitz

Eve Babitz, who has enjoyed a renaissance ever since Lili Anolik’s 2012 profile (and her hugely entertaining 2019 book), was the ultimate L.A. hipster in the ’60s and ’70s (imagine Joan Didion’s more enjoyable and funky friend). She had many famous lovers—including Harrison Ford and Steve Martin and Doors’ front man, Jim Morrison. For a time, Babitz recalls, the future Lizard King was totally uncool because he and his bandmates were film majors. “Even Jack Nicholson wasn’t cool in the ’60s. Being an actor wasn’t cool in the ’60s, because all movies did was get everything all wrong,” she notes. “At least until Easy Rider, being in the movie business was a horrible thing to admit.” The Lizard King was a dork, who knew? Even worse, writes Babitz, was how much Oliver Stone got wrong in his overwrought and moronic, 1991 movie, The Doors. This is Eve at her tart, insightful best.

“You Must”

by James Salter

Sometimes a story is so well-written that you have to pinch yourself to remember it was published in something as ephemeral as a magazine. The December 1992 issue of Esquire featured a handful of amazing pieces, including the charmed cover story by Susan Orlean, “The American Man at Age Ten,” but they all pale in comparison with James Salter’s reminiscence of his time at West Point.

Salter had a distinguished military career after graduating from the Point which he left for the uncertainties of the writing life. Fortunate for us. His prose is lapidary but lyrical in this fascinating meditation on tradition, honor, and duty: “What you had been before meant something—athletic ability mattered, of course, but it was not always enough to see you through. The most important quality was more elusive; I suppose it could be called dignity, but it was not really that. It was closer to endurance. You were never alone. Above all, it was this that marked the life.”

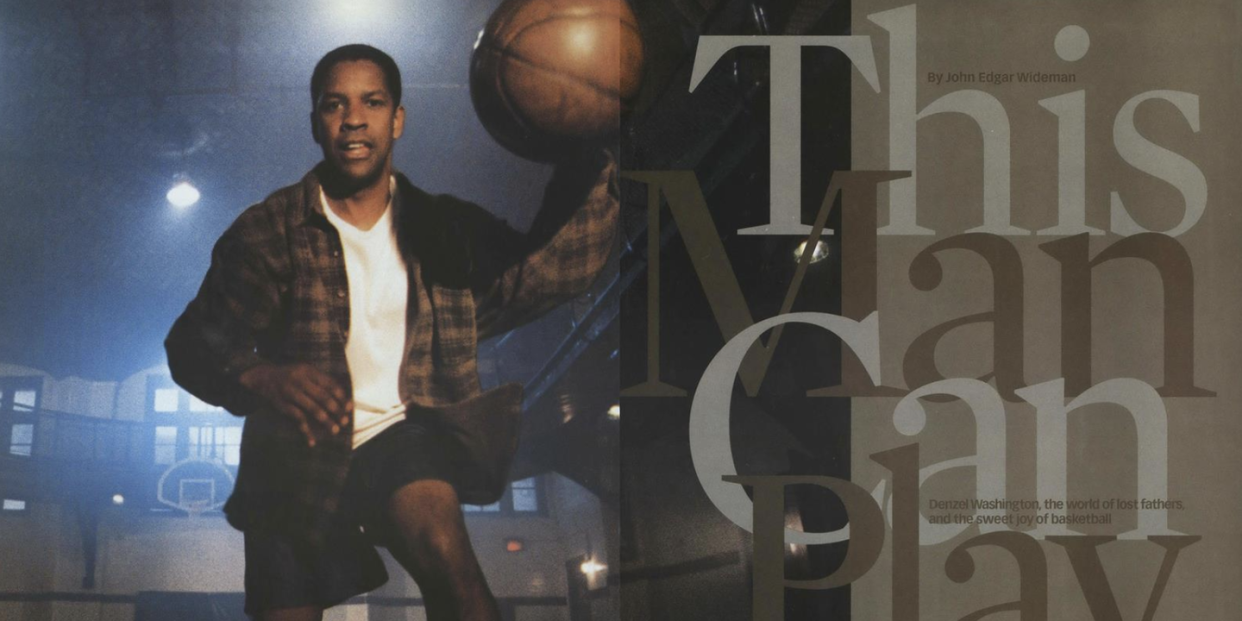

“The Man Can Play”

by John Edgar Wideman

It is a time-honored stunt in the magazine business to get a novelist to write non-fiction. Sometimes, as in the case with Denis Johnson’s dispatches from Saudi Arabia in the early ’90s, it offers brilliant results. Most of the time, the pieces are throwaways or weird curiosities (like James Baldwin’s 1960 profile of Ingmar Bergman), which is what makes the pairing of novelist John Edgar Wideman and Denzel Washington so rewarding.

What could be more trivial to a writer of Wideman’s stature than a celebrity profile? Yet he elevates the form and is an ideal match for Washington, who was filming Spike Lee’s father/son hoops drama, He Got Game at the time. Wideman—no stranger to his own father/son saga— was a standout collegiate hoops star and writes as well about the game as anyone, ever. But in this portrait, he goes deep with Washington on the subject of fathers and sons. And part of what makes it so special is that you can see how much Washington respects, admires and trusts Wideman.

You Might Also Like