The All-Time Greatest Films Directed by Women

[Editor’s note: The below piece was originally published on February 26, 2019. It has been expanded from the 100 greatest films directed by women of all time to the 111 greatest, as of October 3, 2020.]

For as long as there have been movies, there have been women making them. When the Lumière brothers were shocking audiences with their unbelievable depiction of a running train, Alice Guy-Blaché was pioneering her own techniques in the brand-new artform. When D.W. Griffith was pioneering advances in the art, and building his own studio to make his work, Lois Weber was doing, well, the exact same thing.

More from IndieWire

Where to Watch This Week's New Movies, from 'Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret' to 'R.M.N.'

Cannes Breaks Its Own Record for Female Filmmakers in Competition (Again)

When Hollywood was deep in its Golden Age, Dorothy Arzner, Dorothy Davenport, Tressie Souders, and many more women were right there, making their own films. It’s not even a trend that really abated, because it was never a trend. For so long, women being filmmakers was simply part of the norm, and while recent studies have made it clear that the industry needs a wake-up call when it comes to the skills of some of our finest working filmmakers (who just so happen to be women), strides continue to be made.

But the riches are there, and they are decades-deep. The IndieWire staff put together this list of the 100 All-Time Greatest Films Directed by Women to celebrate the work of creators who have been making their mark on cinematic culture since it began. Our writers and editors suggested over 200 titles and then voted on a list of finalists to determine the ultimate ranking.

We hope it’s a list that captures the wide range and diversity of the work women create behind the camera, and a reminder that female directors have put their mark on every decade, genre, and kind of film, and will continue to do just that.

111. “First Cow” (Kelly Reichardt, 2020)

Few filmmakers wrestle with what it means to be American the way Kelly Reichardt has injected that question into all of her movies. In a meticulous fashion typical of her spellbinding approach, “First Cow” consolidates the potent themes of everything leading up to it: It returns her to the nascent America of the 19th century frontier at the center of “Meek’s Cutoff,” touches on the environmental frustrations of “Night Moves,” revels in the glorious isolation of the countryside in “Certain Women,” and the somber travails of vagrancy at the center of “Wendy and Lucy.”

Mostly, though, “First Cow” unfolds like “Old Joy” in the Oregon Territory. Once again, Reichardt has crafted a wondrous little story about two friends roaming the natural splendors of the Pacific Northwest, searching for their place in the world. The appeal of this hypnotic, unpredictable movie comes from how they find that place through mutual failure — which leads them to steal milk from the cow of the title in a desperate attempt to kickstart a bakery business in the woods. Their plight unfolds in an early, untamed America, with rich implications that gradually seep into the frame. Reichardt excels at communing with natural beauty and humankind’s complex relationship to it, but “First Cow” pushes that motif into timeless resonance. —EK

Rent or buy on Amazon.

110. “Atlantics” (Mati Diop, 2019)

Netflix

Several recent movies have explored the refugee crisis as a deadly proposition, from the documentary “Fire at Sea” to “Mediterranean,” both of which focus on dramatic attempts to cross the ocean on rickety boats. The striking distinction of Mati Diop’s “Atlantics” is the way it magnifies the experiences of those left behind. Diop’s gorgeous, mesmerizing feature directorial debut focuses on the experiences of a young woman named Ada (Mama Sané) stuck in repressive circumstances on the coast of Senegal after her boyfriend vanishes en route to Spain. But it’s less fixated on his departure with other locals than its impact on Ada, and the community around her, as it contends with the eerie specter of the boys who went away.

An actress and filmmaker whose experimental shorts touch on similar themes, Diop’s first feature casts a tricky spell that might not click for some viewers on an initial viewing, until they think it over, and it all makes sense: More than a superb neorealist fable, “Atlantics” is in fact a powerful work of fantasy, weaving supernatural conceits into an absorbing vision of alienated seaside life. It’s a ghost story in which everyone’s haunted by the desire to escape, and a beguiling tale of romantic yearning like no other. —EK

Stream on Netflix.

109. “A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood” (Marielle Heller, 2019)

Sony

“A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood” is designed to sneak up on you. In the hands of a lesser storyteller, the saga of a bitter reporter who learns to appreciate life after forging a friendship with Fred Rogers would resort to cheap, maudlin devices. With iconic everyman Tom Hanks as the smiling children’s television host, the formula writes itself, and most people will probably assume they know every beat of the movie sight unseen.

Director Marielle Heller, however, excels at pulling heartstrings from sturdy foundations, injecting smart and insightful details into material that could easily default to sentimentality. Heller works backward by digging into the gooey material and mining for substance in surprising places. As a fictionalized version of journalist Tom Junod, Matthew Rhys plays a new father and disgruntled magazine journalist whose puff piece on Rogers turns into a transcendent, life-changing encounter with pure, unbridled optimism. The movie, which unfolds within the confines of an imaginary “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” episode, lingers in the character’s appeal. The wondrous closing scene, a wordless moment with Rogers after the production wraps up for the day, reminds that this sweet, unassuming movie has deeper sensibilities lurking beneath its surface, just like Rogers himself. —EK

Stream on Hulu via Starz; stream on Amazon via Starz; buy on Amazon.

108. “The Farewell” (Lulu Wang, 2019)

Courtesy of a24

Anyone with a large Chinese family going back several generations will probably appreciate much about the one depicted in tender detail in “The Farewell,” director Lulu Wang’s touching and understated second feature. For everyone else — this critic included — Awkwafina’s performance is a terrific gateway. The rapper-turned-actress’ best performance takes a sharp turn away from her zany supporting roles for a restrained and utterly credible portrait of cross-cultural frustrations. As a Chinese-American grappling with the traditionalism of her past and its impact on the future, she’s the central engine for the movie’s introspective look at a most unusual family reunion.

Based on a 2016 episode of “This American Life” drawn from Wang’s own experiences, “The Farewell” centers on Billi, an out-of-work New York writer who learns from her parents that her beloved grandmother — that is, her “Nai Nai” (Zhao Shuzhen) — has terminal cancer. While this premise could have birthed a quirky dramedy, Wang’s restrained approach instead yields a slow-burn immersion into her character’s life, as she struggles with the conflicting emotions of loyalty and resentment that define her adult life. “The Farewell” delivers a remarkable window into Asian American identity to which future audiences will surely relate, and a welcome introduction to a filmmaker who’s just getting started.

Beyond all that, however, “The Farewell” stands up to the hype because it remains so unclassifiable — defined better by its premise than any single genre, the movie goes from family dramedy to thriller and back again before transforming into something else altogether, a snapshot of cross-cultural confusion utterly in touch with the present moment. —EK

Stream, rent, or buy on Amazon.

107. “Never Rarely Sometimes Always” (Eliza Hittman, 2020)

Angal Field

Three films into her career, filmmaker Eliza Hittman continues to prove herself as one of contemporary cinema’s most empathetic and skilled chroniclers of American youth. Hittman’s trio of features — “It Felt Like Love,” “Beach Rats,” and “Never Rarely Sometimes Always,” her first studio effort — have all zoomed in on blue-collar teens on the edge of sexual awakening, often of the dangerous variety. Hittman’s ability to write and direct such tender films has long been bolstered by her interest in casting them with fresh new talents, all the better to sell the veracity of her stories and introduce moviegoers to emerging actors worthy of big attention.

The bond between cousins Autumn and Skylar (newbies Sidney Flanigan and Talia Ryder) is the beating heart of “Never Rarely Sometimes Always” which, despite its billing as an abortion drama, isn’t just the wrenching heartbreaker many might expect. Yes, it’s a searing examination of the current state of this country’s finicky abortion laws and the medical professionals tasked with enforcing them (from the small-minded to the big-hearted), and if art can have any impact on its consumers, the film will stick with many of its viewers, perhaps even changing long-held beliefs.

But it’s also a singular look at what it means to be a teenage girl today, and with all the joy and pain that comes with it. Autumn and Skylar will never be as vulnerable as they are right now, straddling the line between child and adult, and doing their damnedest to make the right choices for themselves. No one understands that as keenly as Hittman, but perhaps “Never Rarely Sometimes Always” will remind more people of that naked, terrible fragility and what it means. —KE

Stream on Hulu via HBO Max; stream on Amazon via HBO; buy on Amazon.

106. “One Night in Miami” (Regina King, 2020)

Amazon

On a warm February 1964 night in Miami, self-professed “The Greatest” (a distinction that’s still hard to argue with, even so many decades on) Muhammad Ali defeated Sonny Liston to capture his first World Heavyweight Championship. A 7-to-1 underdog, Ali’s win was hardly expected, but it also somehow felt preordained, a necessary step towards his domination of the sport and then the world. Malcolm X, a close friend of Ali’s and his spiritual guide who would lead him to the Nation of Islam soon after the win, was there. So was soul singer Sam Cooke and NFL superstar Jim Brown.

And when it was all over, when Ali became the greatest, the four close friends celebrated the win together at a local Miami hotel. What transpired on that evening — an evening that, yes, really did happen — belongs to both history and its central foursome, but is now vividly imagined in a film that crackles with all the hopes and fears and dreams and possibilities of both the men it tracks and the blossoming filmmaking talent behind the camera.

While first-time feature director Regina King is not attempting to offer a precise historical transcription of whatever happened that fateful night, what “One Night in Miami” provides is something richer: an emotionally accurate telling, one that always endeavors to find the real people underneath the famous gloss. “One Night in Miami” hits so hard because it remains joyfully, often painfully grounded in what makes a person extraordinary, even when the world isn’t ready for them. —KE

105. “Clemency” (Chinonye Chukwu, 2019)

NEON

Burgeoning star Chinonye Chukwu broke some serious barriers when her second feature picked up the Grand Jury Prize at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival, where she became the first Black woman to win the festival’s biggest prize. But Chukwu’s death row drama goes far beyond nifty superlatives, and this decidedly human and deeply considered drama is a meticulously crafted heartbreaker that would sting no matter when it was made.

Chukwu both wrote and directed the drama, which stars an extraordinarily controlled Alfre Woodard as a prison warden struggling with the emotional demands of her job, many of which come to a head as she prepares to execute a prisoner (Aldis Hodge) mounting a desperate last-minute fight for exoneration. The filmmaker boldly tracks these two characters, brought to life by a pair of very talented leads, as they brace for an inevitable tragedy, making sure neither comes off as hero or villain.

Each scene is a challenge Chukwu’s characters fight through, and she ensures the viewer feels the grueling weight of the situation through pacing and editing. It all leads up to a final ten minutes guaranteed to break your heart (deservedly so, given the craft on offer within the entire film), enough to ensure Chukwu’s place in searing cinema for decades to come. —KE

Stream on Hulu; rent or buy on Amazon.

104. “Hustlers” (Lorene Scafaria, 2019)

STX

Lorene Scafaria’s third film is not only her best yet, it’s also a welcome twist on the crime thriller genre (if we must apply genre distinctions here) and the ripped-from-the-headlines, can-you-believe-this-is real drama. And, yes, it’s also a film about strippers, but more than that, it’s about women doing the best they can in a broken system. It’s also funny, empowering, sexy, emotional, and a bit scary, with most of those superlatives coming care of a full-force performance from Jennifer Lopez genuinely deserving of awards consideration.

For all its touchy subjects and ambiguous answers, “Hustlers” is never anything less than energetic, freight-train-fast, and impeccably plotted. Eventually, Lopez’s compatriot Destiny (Constance Wu) shares a persistent nightmare with the journalist trying to commit the duo’s wild story to paper: she’s riding in a car, and realizes no one is driving, and as she attempts to chuck herself at the steering wheel and the pedals, it’s already too late. Nothing in “Hustlers” feels as out of control as that; instead it’s Scafaria and her ladies, one hand on the wheel, one hand throwing up a blinged-out middle finger to the world that doesn’t value them. No one will make that same mistake with “Hustlers.” —KE

Stream on Hulu via Showtime; stream on Amazon via Showtime; buy on Amazon.

103. “Nomadland” (Chloé Zhao, 2020)

“Nomadland” is the kind of movie that could go very wrong. With Frances McDormand as its star alongside a cast of real-life nomads, in lesser hands it might look like cheap wish fulfillment or showboating at its most gratuitous. Instead, director Chloé Zhao works magic with McDormand’s face and the real world around it, delivering a profound rumination on the impulse to leave society in the dust.

Zhao previously directed “The Rider” and “Songs My Brother Taught Me,” dramas that dove into marginalized experiences with indigenous non-actors in South Dakota. “Nomadland” imports that fixation with sweeping natural scenery to a much larger tapestry and a different side of American life. Inspired by Jessica Bruder’s non-fiction book “Nomadland: Surviving America in the 21st Century,” the movie follows McDormand as Fern, a soft-spoken widow in her early 60s who hits the road in her van, and just keeps moving. The movie hovers with her, at times so enmeshed in her travels that it practically becomes a documentary. Anyone waiting for a big moment won’t find one here: As Fern drives on, the movie embodies that line as a mission statement. —EK

102. “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (Celine Sciamma, 2019)

NEON

Over the past 13 years, Céline Sciamma has become one of the most exciting voices in French cinema, with a string of moving dramas focused on young women that deliver new poignant experiences each time out. From “Water Lilies” to “Tomboy” and “Girlhood,” Sciamma has excelled at probing the coming-of-age drama from fresh angles, assessing emerging sexual identity and rebellious instincts while hovering inside the ambiguous emotions they stir up. That constant fixation has yielded her most confident achievement to date, a warm and lush period romance that hails from familiar traditions even as it corrals them in new directions.

Sciamma’s lyrical 18th century lesbian drama finds young painter Marianne (an understated Noémie Merlant) assigned to paint wealthy heiress Hélo?se (the ever-entrancing Adèle Haenel) over a single summer on a remote island. The setting gradually transforms into a painterly achievement of its own, with the rocky landscapes and ocean waves accentuating the gradual bond between the two women and how it defies the linguistic boundaries of their time. Sciamma compensates for that by using the language of cinema to fill in the gaps: An enchanting, fantastic paean to forbidden love, the movie builds to a series of thrilling operatic moments, including a show-stopping musical number that catapults the story from the boundaries of its setting to achieve a timeless ecstasy. —EK

Stream on Hulu; rent or buy on Amazon.

101. “Little Women” (Greta Gerwig, 2019)

Sony

While it’s consumed with questions of ambition, economics, and a woman’s place in the world, “Little Women” is clearly the work of someone steeped in affection for the novel, and keenly aware of how the concerns of Alcott and the March sisters (loosely based on the author’s own family) have never quite abated, no matter the time. In short: it’s the same “Little Women” that has endured for centuries, given new life with an original narrative conceit, and a level of craftsmanship that’s nothing short of stunning.

Gerwig’s brilliant storytelling conceit, slipping between time and place, sister and sister, is aided by editor Nick Houy, who cuts between scenes through brilliant transitions that will reward repeat viewings: As Jo (Saoirse Ronan) mentions that her sister Amy (Florence Pugh) is in Paris, the story finds her there; a visit to eldest sister Meg (Emma Watson) ends with a fade that moves from the front door of her small house to the somewhat grander entryway of the March family abode, as the angelic Beth (Eliza Scanlen) wiles away her time, missing her sisters. There is no Jo without Amy, no Meg without Beth. Everything is connected or, at least, every March is connected, just as it should be.

Gerwig’s elliptical storytelling weaves both past (seven years earlier) and (relative) present with ease — any confusion is swiftly cleared up through her use of different color palettes between the time periods, and occasionally, Jo’s very different haircut — cutting more quickly, and nestling together more closely, as the emotion ramps up. Gerwig’s “Little Women” offers its own delightful storybook polish, in its own unique terms, and what a comfort that is. —KE

Stream on Hulu via Starz; stream on Amazon via Starz; buy on Amazon.

100. “American Psycho” (Mary Harron, 2000)

Lionsgate Films

Mary Harron did something it feels like only she could do: find subtlety in the sensationalism of Bret Easton Ellis’ novel about the murderousness of the upwardly mobile. And this in a movie where a nude, sinewy Christian Bale drops a chainsaw down a spiral staircase to cut short the life of a prostitute. But as with “I Shot Andy Warhol,” she manages this by getting specific. Harron revels in the details of Yuppie Patrick Bateman’s world — the bespoke business cards, self-care rituals involving cold-gel eye masks and herbal facials that would put Narcissus to shame, flaunting your plastic at dinners out, taking pride in a music collection well-stocked with Phil Collins and Huey Lewis & the News, and all manner of other Reagan Era acts of conspicuous consumption. Harron demonstrates a profound understanding that our trajectories through life demand that we “perform” who we are — or, at least, who we think we are. What happens if we lose control of the script? —CB

Rent or buy on Amazon.

99. “Frozen” (Jennifer Lee & Chris Buck, 2013)

Moviestore/REX/Shutterstock

Jennifer Lee’s ascent to becoming Walt Disney Animation’s chief creative officer, the most powerful woman in animation, began with her script contributions to “Wreck-It Ralph.” Lee helped shape the funny, self-determined, yet glitchy Vanellope into a subversive anti-Princess. That led to her writing and co-directing “Frozen” with Chris Buck, transforming the troubled “Snow Queen” adaptation into a warm and witty sibling love story between sisters Anna (Kristen Bell) and Elsa (Idina Menzel).

The Oscar-winning blockbuster solidified the new Disney renaissance, leveraged the studio’s hand-drawn legacy to guide the innovative CG animation, and became the most feminist take yet on the musical princess fairy tale. While Lee puts the finishing touches on “Frozen 2” (out November 22), she’s reshaping the studio with greater inclusion and diversity in storytelling. —BD

Stream on Disney+; rent or buy on Amazon.

98. “I Am Not a Witch” (Rungano Nyoni, 2018)

Film Movement

Zambian-Welsh director Rungano Nyoni’s provocative satire revolves around a young girl sentenced to life imprisonment at a state-run witch camp. Counting Greek filmmaker Yorgos Lanthimos as kindred artistic spirit, Nyoni’s film is an at times unapologetically confounding work that tackles misogyny in Zambia. The film was shot over six weeks in the fall of 2016 around the country’s capital Lusaka, with a cast of largely non-professional local actors, led by a remarkable performance by nine-year-old Margaret Mulubwa.

One of very few Zambian films to ever screen at the Cannes Film Festival, the momentous occasion led to Zambia’s president, Edgar Lungu, issuing a national congratulatory communiqué to the film and filmmaker, as well as an introduction of new film policies influenced by the realization of how important cinema can be in serving as an international postcard for the southern African nation. The stylistically fresh tragicomic film is the debut feature of an artist who clearly has a lot to say, and does so beautifully with this stunning work of magical realism. —TO

Rent or buy on Amazon.

97. “They” (Anahita Ghazvinizadeh, 2017)

Anahita Ghazvinizadeh

Making your Cannes debut before the age of 30 is an almost unbelievable achievement, but when you’ve studied with Abbas Kiarostami and can boast Jane Campion as an executive producer, your bona fides pretty much speak for themselves. In her evocative first feature, Iranian director Anahita Ghazvinizadeh explores the complicated and lately in vogue subject of childhood gender identity with an artful and empathic precision. Ghazvinizadeh leaves the birth gender of her protagonist, J, ambiguous, and surrounds them with an understanding older sister and her Iranian boyfriend. Set in Chicago, with some scenes filmed partly in Farsi, “They” embodies a contemporary international culture that makes the story feel universal, even as J’s journey is achingly specific. —JD

Rent or buy on Amazon.

96. “The Secret Garden” (Agnieszka Holland, 1993)

Murray Close/Am Zoetrope/Warner Bros/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

The versatile Agnieszka Holland has frequently fashioned her films around characters struggling with unfamiliar circumstances. Herself a wanderer, she made this tale of a 10 year-old orphan girl returned to her parents’ England a resonant fable about loneliness and friendship. What other cutting edge, festival-regular director has ever so easily transitioned to a G-rated studio hit? The success of this critic-supported family film sparked a resurgence of intelligent family films like Alfonso Cuaron’s “A Little Princess” and “Babe,” both also G rated. Of a piece with her other films, yet distinctive on its own, this is one of the best examples of a major director seamlessly integrated into a studio production and utilizing top talent — Roger Deakins, the D.P., as well as a production designer who later oversaw “Harry Potter,” and a cast that included Maggie Smith — and it makes one wish she had more opportunities. —TB

Stream, rent, or buy on Amazon.

95. “Rambling Rose” (Martha Coolidge, 1991)

New Line Cinema

Adapted from his Depression-era Georgia novel by “The Graduate” co-screenwriter Calder Willingham, “Rambling Rose” broke out Laura Dern in the title role of a ripe young housemaid bursting with sex appeal, who riles up the father (Robert Duvall) and son (Lukas Haas) in her household as well as many of the men in her vicinity. Charming, flighty Rose earned Dern her first Oscar nomination — along with her mother Diane Ladd. With her seventh feature film, Coolidge scored rave reviews (if not box office) and the Independent Spirit Award for Best Director for capturing just the right sexy, comedic tone for this poignant, impeccably crafted period dramedy. —AT

Buy on Amazon.

94. “Monsoon Wedding” (Mira Nair, 2001)

Mirabai/Delhi Dot Com/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

Harvard grad Mira Nair knows that her best movies are the ones that are the most challenging, independent and personal, such as “Kama Sutra: A Tale of Love,” “Mississippi Masala” and “Monsoon Wedding.” She started her directing career with 1988’s vérité-style “Salaam Bombay!,” her feature debut, which was nominated for a Best Foreign Film Oscar. Next came the steamily sexy multiethnic romance ”Mississippi Masala,” starring Denzel Washington and Sarita Choudhury, which became an arthouse hit.

A decade later Nair returned to her roots with festival hit “Monsoon Wedding.” Nair threads several romances through this tumultuous family drama, which culminates in the traditional Indian-arranged wedding of Aditi (Vasundhara Das) with Texas emigre Hemant (Parvin Dabas), who she comes to know in the weeks leading up to the wedding. She had broken off her relationship with an older man, but impulsively gets together with him just before the wedding. When she tells her fiancé, he forgives her. Nair expertly navigates the colorful subplots and local decor with constantly moving handheld cameras. There is never a dull moment, and we root for the happy couple to finally consummate a successful marriage. —AT

Rent or buy on Amazon.

93. “The Breadwinner” (Nora Twomey, 2017)

StudioCanal

With her debut animated feature, Irish director Nora Twomey of Cartoon Saloon delivered a powerful story of political oppression with sensitivity and hope, earning GKids its 10th nomination. Based on the popular YA novel by Deborah Ellis, “The Breadwinner” concerns a strong-willed 11-year-old Afghan girl who poses as a boy to help her family survive under threat from the Taliban after her father is imprisoned as a dissident. Twomey deftly balanced the personal with the political in exploring new dramatic territory with a naturalistic fervor. She also updated the turbulent events to make it more topical, with the fall and resurgence of the Taliban, and the rise of ISIS. But she rightly keeps the focus on the courageous 11-year-old Parvana (voiced by Canadian newcomer Saara Chaudry), who struggles to reunite her family in a stirring rite of passage. —BD

Rent or buy on Amazon.

92. “Nitrate Kisses” (Barbara Hammer, 1992)

Metrograph/Hammer Archive

Barbara Hammer, one of the most prolific and esteemed lesbian filmmakers, is someone who mainstream filmgoers — and even more discerning cinephiles — probably don’t know. While the term “experimental film” may seem opaque to laypeople, Hammer’s work is marked by provocative playfulness. Her work often explores queer women’s sexuality and sexual subcultures, and her first feature film, “Nitrate Kisses” is a prime example. A consummate film archivist, Hammer intercuts footage from the 1933 homoerotic film “Lot in Sodom” with interviews with both gay and straight couples and images from LGBT history to create a 63-minute meditation on queer history and sexuality. Hammer’s influence, and the act of unearthing and reclaiming queer history, can be felt in countless queer films that followed, most notably Cheryl Dunye’s “The Watermelon Woman.” —JD

91. “Outrage” (Ida Lupino, 1950)

Rko/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

Terse, tense, and tough, Ida Lupino evokes so much of her characters’ anxiety and psychological state with a direct use of the camera. “Outrage” has a slightly wider scope than Lupino’s similarly effective independently-made noirs. Here, in a film where the subject is rape — a taboo topic for the 1950s that Lupino handles with customary bluntness — she uses urban and suburban landscapes to give her character’s situation a societal context. The film is way ahead of its time in terms of the way it handles its subject matter, while the climactic scene is haunting, along with a chase scene that demonstrates Lupino’s skill-set was virtually boundless. –CO

90. “35 Shots of Rum” (Claire Denis, 2008)

Snap Stills/REX/Shutterstock

The endlessly versatile Claire Denis’ attempt at her version of an Ozu family drama is sublime. Early in production, Denis smartly abandoned trying to mirror the Japanese master’s static wide shots, and liberated the camera and cinematographer Agnes Godard to probe the natural loosening of the bond between a father and his young adult daughter. Denis regular Alex Descas is never better as a widowed father coming to terms with his daughter starting a life of her own at the very moment he – an African immigrant, married to a German woman – is also realizing that his entire existence revolves around a public transportation job he’ll likely lose to forced early retirement.

Denis’ eye for the social and historical implications of her story is particularly sharp here, but never didactic or forced. The film contains a dance scene, set to the Commodores’ “Nightshift,” that is incredibly empathetic, sensual, and bittersweet – the essence of the film boiled down to four swaying bodies and averted glances without a word being spoken. In other words, Denis at her purest. –CO

Stream on Amazon via Fandor.

89. “Near Dark” (Kathryn Bigelow, 1987)

Moviestore/REX/Shutterstock

Kathryn Bigelow couldn’t get her revisionist Western funded, so she rode the 1980s vampire wave to make this unique genre hybrid. A gorgeous, gory, and (romantically) gooey film set in a small midwestern town, “Near Dark” is a complicated love story about a vampire Mae (Jenny Wright) and Caleb (Adrian Pasdar), the boy she falls in love with and bites one very eventful evening, but whose essence proves to be non-violent, making her fall for him that much more. Bigelow’s nomadic vampire tribe, however, is violent and the director brings visceral brutality in a bar scene that is anything but romantic. All of this capped off with one of those ’80s-inflected Tangerine Dream scores that transports audiences to an entirely different headspace. For those who wish Bigelow never left genre for prestige, this film is a reminder of how dense her “less serious” films were right from the start. –CO

Buy on Amazon.

88. “Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance” (Alanis Obomsawin, 1993)

Channel Four

The Oka Crisis lasted 78 tense days in 1990, leaving two dead and bringing to light the dispute between the Mohawk people and the Canadian government. Alanis Obomsawin captured it vividly in “Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance,” which was produced by the National Film Board (and remains available to watch in its entirety). Made under difficult conditions — Obomsawin recorded the sound herself, and a police perimeter made it all but impossible to see beyond their barricade — the documentary captured history in the making with a sense of urgency that remains rare in nonfiction filmmaking. —MN

Stream, rent, or buy on Amazon.

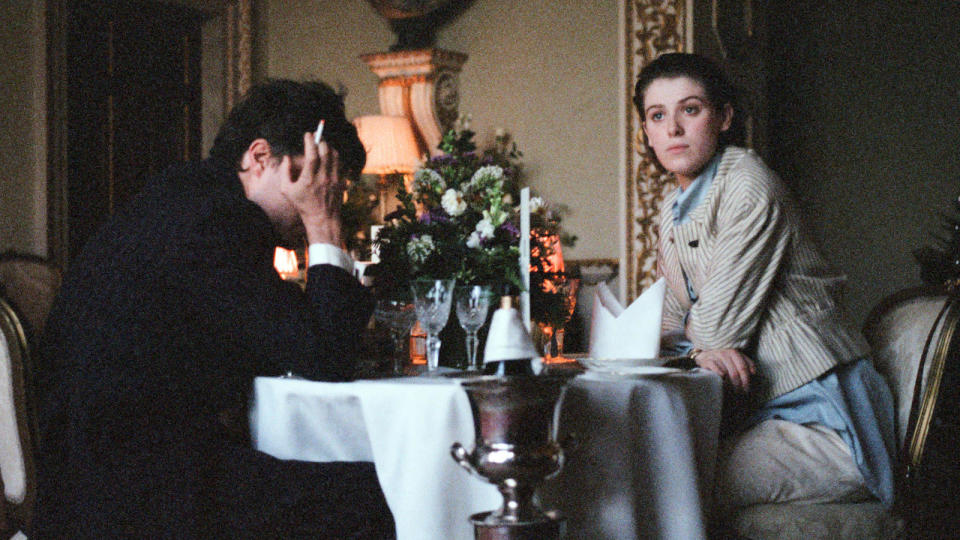

87. “The Souvenir” (Joanna Hogg, 2019)

A24

There isn’t much of a story in Joanna Hogg’s Sundance Grand Jury Prize-winning, and wholly heartfelt and searingly honest, “The Souvenir.” The British director, somehow a breakthrough talent for the last 30 years, has always been less interested in plot than condition. Nevertheless, this elliptical, semi-autobiographical study of creative awakening lands with the weight of an epic. Set in the early 1980s, shot with the gauzy harshness of “Phantom Thread,” and named after an 18th century rococo painting by Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Hogg’s most affecting work to date charts the doomed romance between a young filmmaker (the remarkable Honor Swinton Byrne) and the troubled older man (Tom Burke) who sparks her potential.

More than just a tender self-portrait, “The Souvenir” becomes a diorama-esque dissection of that volatile time in your life when every molecule feels like it’s restlessly vibrating in place, and even a brief encounter with another person has the power to rearrange your basic chemistry; when you’re so desperate to become yourself that you’ll happily believe in anyone else you happen to find along the way. It’s a masterpiece from a filmmaker who’s been major from the start. —DE

Stream, rent, or buy on Amazon.

86. “Gas Food Lodging” (Allison Anders, 1992)

Cineville Inc/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

For her sophomore feature, Anders wrote and directed this charmingly well-observed $1.3 million family drama based on Richard Peck’s young adult novel “Don’t Look and It Won’t Hurt” about Nora, a truck stop waitress (Brooke Adams) raising two teenage daughters, Trudi (Ione Skye) and Shade (Fairuza Balk) in a New Mexico trailer park. Trudi defies her protective mother to drop out of school and waitress, and hooks up with a man (Robert Knepper) who gets her pregnant; she moves away to have the baby. Shade falls in and out of crushes while trying to set her mother up with a man (Chris Mulkey) who she has already dated. “Gas Food Lodging” played Sundance and Berlin and broke out Anders as a filmmaker; Balk took home the 1993 Independent Spirit Award for best female lead. —AT

Rent or buy on Amazon.

85. “Something’s Gotta Give” (Nancy Meyers, 2003)

Columbia Pictures

It’s a testament to the well-furnished, white-turtlenecked genius of Nancy Meyers that the most Nancy Meyers film ever made is also the best Nancy Meyers film ever made; the fact that “Something’s Gotta Give” often feels like a deranged parody of the rom-com writer-director’s ultra-charming wealth porn is part of the reason why it works so well (other reasons include the nuclear-grade chemistry between Jack Nicholson and Diane Keaton, the decision to cast Keanu Reeves as a hunky Hamptons doctor, and a scene where a dozen Nicholson look-alikes flash the camera their prosthetic butts).

All of Meyers’ usual tropes are jacked up to 11: Palatial kitchens, rich people resisting their feelings for each other, zesty lines of dialogue that combine the wit of Billy Wilder with the wisdom of someone who knows why a sixtysomething woman might find herself shouting “I DO like sex!” From the Crazy Town needle drop that opens the film to the Parisian showdown that bids it adieu, “Something’s Gotta Give” takes place in a total fantasyland where love is the only luxury no one can afford, and having sex with someone half your age is just the first step toward finding true happiness with her mother. But the deeper Meyers dives into this alternate dimension, the more sense that it all starts to make. And by the time Nicholson looks Keaton in the eye and says, “Erica, you are a woman to love,” well, you know exactly what he means. —DE

Stream, rent, or buy on Amazon.

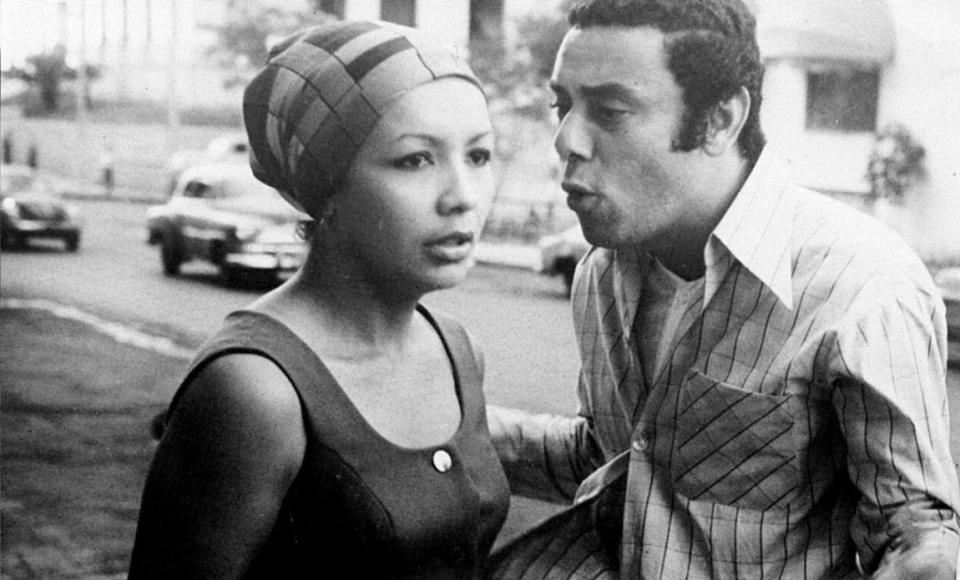

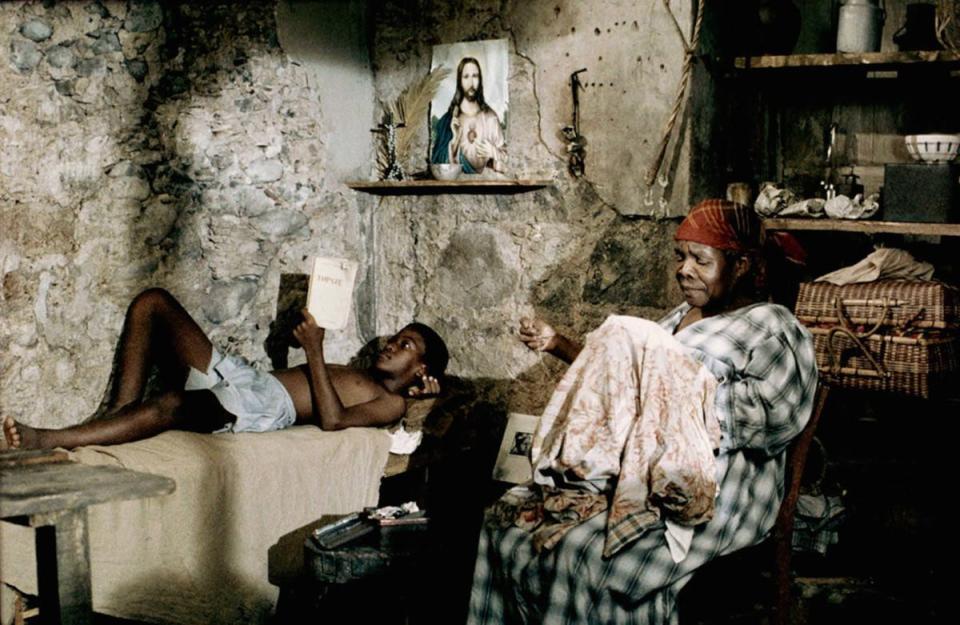

84. “One Way or Another” (Sara Gómez, 1974)

Sara Gómez

A pioneering figure of Cuban cinema, Sara Gómez was one of the first women filmmakers to work under the supervision of Cuba’s post-Revolutionary film bureau. The 16mm “One Way or Another” (“De cierta manera”), her only feature film, was the first by a Cuban woman filmmaker and remains one of very few films made by an Afro-Cuban director.

A romantic drama told docu-drama style, the love story unfolds amid a community of marginalized Afro-Cubans shortly after the Revolution of 1959, while serving as a critique of the Revolution from the point of view of Cubans of African descent, to demonstrate how accepted views of race, class, and gender in Cuban culture pose threats to the far more momentous goal of creating a truly equal society. Sadly, Gómez died during post-production of the film, at age 31, and would not see its full realization. A film that was as provocative in its form as in the subject matter it dared tackle, “One Way or Another” would be finished by colleagues several years later.—TO

83. “Crossing Delancey” (Joan Micklin Silver, 1988)

Getty Images

Nebraskan-turned-New Yorker Silver launched her feature directing career in 1975 with an authentic portrait of 19th-century Jewish immigrants in Lower Manhattan, “Hester Street,” starring Oscar nominee Carol Kane. Silver gives New York Jewish culture an ’80s update in charming romance “Crossing Delancey,” starring Amy Irving as 30ish Upper West Side yuppie Isabelle Grossman, a bookstore staffer with literary pretensions. She loves schlepping down to the Lower East Side to visit her Bubbe (Reiz Bozyk), who insists on hiring a matchmaker (hilarious Sylvia Miles) for her rapidly aging granddaughter. When Isabelle is set up with Sam (Peter Riegert), who inherited his father’s pickle shop in Bubbe’s neighborhood, she finds him charming but backs away from his profession. But Sam won’t take no for an answer when it comes to the woman he loves. —AT

Rent or buy on Amazon.

82. “Appropriate Behavior” (Desiree Akhavan, 2014)

Parkville/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

Loosely based on Desiree Akhavan’s own sexual coming-of-age, the Sundance hit is a startlingly open and honest examination of owning up to one’s desires, even when those same desires threaten pretty much every other facet of life. Written by, directed, and starring Akhavan as the newly single Shirin, “Appropriate Behavior” charts the Brooklynite’s wacky decline back into the dating scene, complicated by reappearances by her beloved ex, a family who is shaken by revelations about her sexuality, and a new (and very odd!) job teaching children.

Oh, and it’s funny. Akhavan’s knack for putting her characters into insane situations and then forcing them out the other side is truly inspired (the film features perhaps the most uncomfortably amusing threesome in modern cinema). It’s shaggy and fun in all the very best ways, but it also gets to the heart about how hard it can be to be yourself, and why it’s always worth it. —KE

Stream, rent, or buy on Amazon.

81. “After the Wedding” (Susanne Bier, 2006)

Zentropa

Denmark’s Susanne Bier has had a titanic impact, with an Oscar for “In a Better World” and her recent “Bird Box” becoming an international sensation. Her initial Danish films brought her to attention, parallel to Lars von Trier’s Dogme movement but with a style of their own. Like many women directors, she focused on family situations with a keen eye. But “After the Wedding” was unconventional and subversive on its own. Mads Mikkelsen played a manager of an Indian orphanage who returns to unexpected personal complications as he tries to sustain funding. The theme of parenthood often seen in female-directed films is in the forefront here, with Bier skillfully subverting it to create a compelling drama that also satirized Danish norms. —TB

Stream on Hulu via Starz; stream on Amazon via Starz; buy on Amazon.

80. “Girlfriends” (Claudia Weill, 1978)

Warner Bros/Courtesy Everett Co.

An American indie director who made the jump to television long before it was cool — though she managed to snag directing gigs on the sort of shows that predicted the so-called Golden Age of Peak TV we’re currently steeped in — Claudia Weill made her bones with her 1978 feature narrative debut “Girlfriends,” which captures the pains and pleasures of deep female friendship (and urban malaise) with a wisdom few filmmakers have been able to match.

A BFF story that’s instantly recognizable, it follows a pair of New York strivers who are pulled apart by ambition, romance, and possibly just wanting different things. It feels lived in and real, and that it doesn’t offer any easy endings or answers speaks to Weill’s ability to capture truth, even when it’s uncomfortable and a little bit heartbreaking. —KE

Rent or buy on Amazon.

79. “Boys Don’t Cry” (Kimberly Peirce, 1999)

Fox Searchlight

Arriving on the tail end of the New Queer Cinema’s boom time, Kimberly Pierce’s wrenching drama based on the true story of Brandon Teena was the first movie told from the perspective of a transgender man, albeit one that ended in tragedy. Before the film’s grisly ending, Brandon shares a sweet romance and is accepted as a man by an affirming group of friends. Told with tenderness and grit, the movie offered a searing critique of a world that violently rejected Brandon for his gender identity.

While Hilary Swank’s casting in her breakout role is not a paragon of representation, the gentle spirit and handsome spark with which she imbued Brandon went a long way to humanizing trans men for mainstream audiences. Pierce straddled the line between the rule-breaking of the New Queer Cinema and an authenticity-seeking contemporary trans audience, which has unfairly villainized Pierce herself, rather than the culture at large, for co-opting trans stories. —JD

Rent or buy on Amazon.

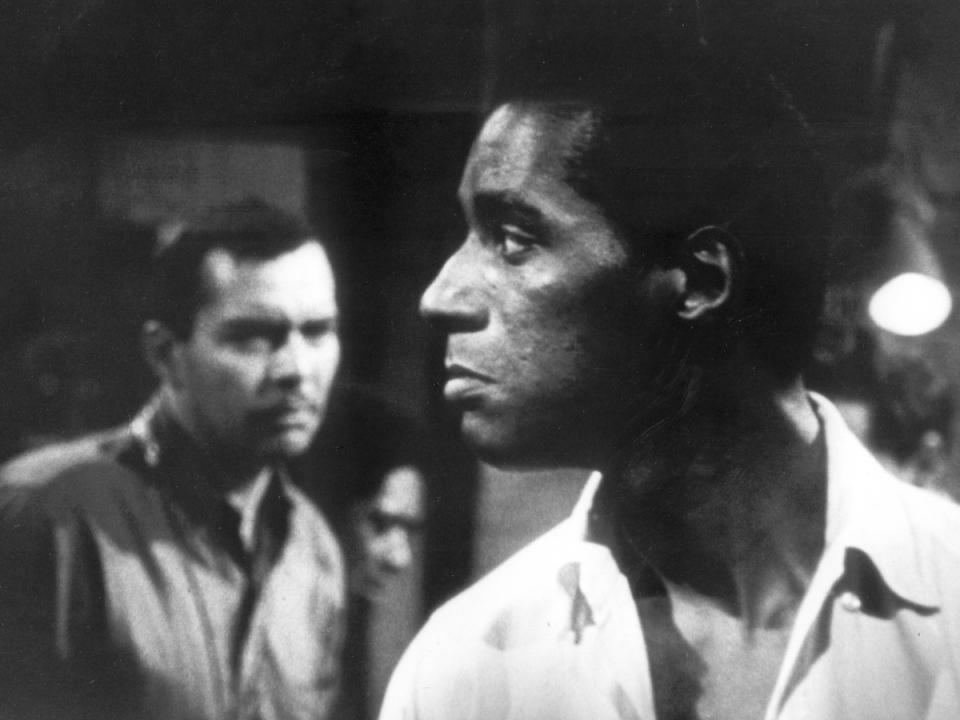

78. “The Connection” (Shirley Clarke, 1961)

Photofest

Shirley Clarke was one of the great American filmmakers of the ‘60s and ‘70s, but the magnitude of her work remains under-appreciated. While documentaries like “Ornette: Made in America” and “Portrait of Jason” are key to understanding her ability to scrutinize underrepresented figures in American culture, her 1961 debut “The Connection” is the most remarkable illustration of her cinematic ambitions: At once a slow-burn chamber piece and a found-footage thriller, the movie finds jazz musicians hanging out in an apartment waiting for their heroin delivery, as the men become cognizant of the camera and the filmmaker behind it.

The scenario grows increasingly frantic once the drugs arrive and the musicians cajole the director into trying drugs with them. Nearly 40 years before “The Blair Witch Project,” Clarke understood the power of using non-fiction cinematic tropes to convey an unsettling degree of authenticity, but she had far greater aims than jump scares. “The Connection” is a riveting social-realist thriller about the travails of addiction, and the dangerous shadow it cast on an underground culture in desperate need of an escape. —EK

77. “Enough Said” (Nicole Holofcener, 2013)

Searchlight

Nicole Holofcener’s movies tend to focus on conflicted women, but the men sure don’t have it any easier. With the tender-hearted “Enough Said,” her first studio production and one of the late James Gandolfini’s final screen credits, Holofcener returns to the terrain of her 1996 debut “Walking and Talking” with another awkward romance threatened by conflicting agendas and poor judgement.

As much as “Enough Said” revolves around single mother and neurotic masseuse Eva (Julia Louis-Dreyfus), it also foregrounds the impact of her romantic confusion on good-natured suitor Albert (Gandolfini), who doesn’t realize that Eva has been treating his ex-wife Marianne (Catherine Keener) and secretly gleaning information from her about Albert’s flaws. The cringe-worthy setup might provide sufficient fodder for an episode of “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” but Holofcener’s unassuming script gives the situation a more delicate balance of understated humor and melancholy. That’s Holofcener’s filmmaking appeal in a nutshell, and “Enough Said” is the perfect conduit to her wonderful body of work. —EK

Rent or buy on Amazon.

76. “Antonia’s Line” (Marleen Gorris, 1995)

Moviestore/REX/Shutterstock

Marleen Gorris’ “Antonia’s Line” was the first (of three to date) female-directed Oscar Foreign Language winners, as well as the most successful 1996 subtitled release in the U.S. (adjusted over $8.5 million). Unabashedly feminist in its multi-decade portrayal of a matriarchal society in an otherwise typical post-World War II Netherlands village, its mixture of joy and tragedy, humor and anger clicked at a time when female directors sometimes felt the need to soften themes in order to make their films more acceptable. “Antonia’s Line” packs a punch while providing pleasure, with an earthiness that celebrated female strength outside of urban or intellectual circles. Gorris had previously gained attention for her debut “A Question of Silence” which saw limited release but was seen as an important film in the early 1980s. She went on to film Virginia Woolf’s “Mrs. Dalloway” with Vanessa Redgrave. —TB

Rent or buy on Amazon.

75. “Thirteen” (Catherine Hardwick, 2003)

Fox Searchlight Pictures

Catherine Hardwicke won best director honors at the 2003 Sundance Film Festival for her tough-as-nails approach to the coming-of-age drama in “Thirteen.” The film stars Evan Rachel Wood as a 13 year old who begins dabbling in sex, drugs, and partying after befriending a popular girl at school (Nikki Reed), much to the detriment of her relationship with her mother (Holly Hunter, Oscar nominated). Shot almost entirely with handled cameras, Hardwicke unleashes her character’s rage and free fall through a cinéma vérité visual approach that turns the narrative into a visceral roller coaster of emotion. Few coming of age movies are as hard hitting as “Thirteen.”—ZS

Rent or buy on Amazon.

74. “High Art” (Lisa Cholodenko, 1998)

October/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

Lisa Cholodenko’s feature film debut is as alluring and mature as any of her subsequent works, a fully formed dip into a toxic relationship that also feels ripped from reality. It’s a tricky film, but it doesn’t ever try to evade its audience, instead gracefully moving viewers from one stop to the next, until it’s all so clear, so unavoidable. Featuring a revelatory Radha Mitchell as a twentysomething feeling her way through the world and a second-act Ally Sheedy as her unexpected inspiration, mentor, and ultimate entry into a wholly different world, it’s the kind of whip-smart drama that isn’t afraid of the erotic, but that also revels in the intellectual and the emotional. —KE

Rent or buy on Amazon.

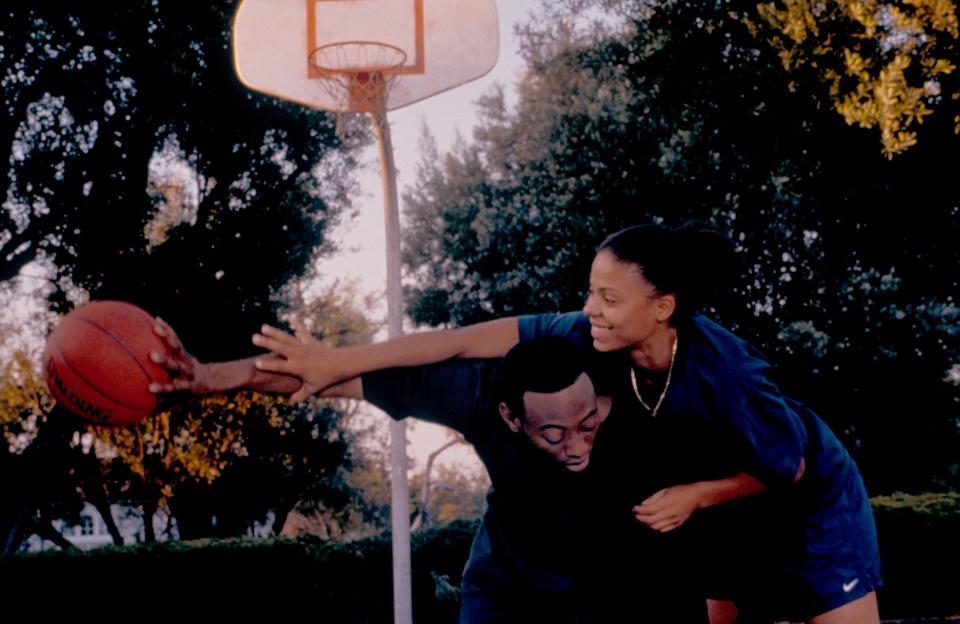

73. “Love & Basketball” (Gina Prince-Bythewood, 2000)

Moviestore/REX/Shutterstock

All’s fair in love and basketball, but that doesn’t make it any easier when you lose — whether on or off the court. Gina Prince-Bythewood made her directorial debut with this film, which she also wrote, with Sanaa Lathan and Omar Epps playing next-door neighbors in Los Angeles who fall for the game just as surely as they fall for each other. Basketball has traditionally proven more difficult for filmmakers to romanticize than baseball and even football, but Prince-Bythewood’s hoop dream is easy to get lost in: Sexy and swooning, it was a promising first act for the “Beyond the Lights” helmer. —MN

Rent or buy on Amazon.

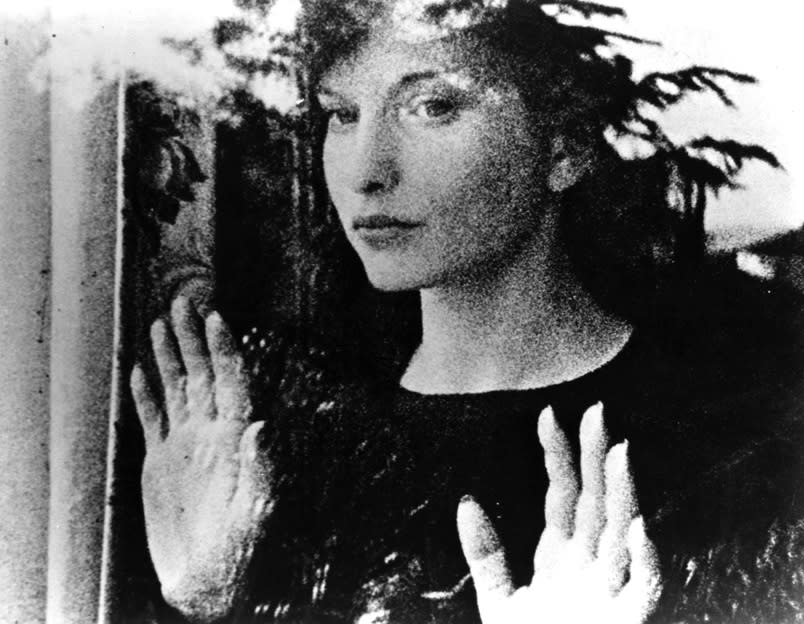

72. “Orlando” (Sally Potter)

Sony Pictures Classics

Tilda Swinton had been working in film for almost a decade before she landed the title role in “Orlando,” but Sally Potter’s sweeping Virginia Woolf adaptation — about a young nobleman who obeys her queen’s order to never grow old, and then abruptly transforms into a woman a couple hundred years later — is the movie that forever crystallized her screen presence. Allowing her star to take a step back from the story (and speak directly to the audience) while also leading it with her heart, Potter found a way to weaponize the elemental quality that Swinton had first expressed in her collaborations with Derek Jarman.

Her movie captures the duality of its star. It’s sexual, but never objectifying. Voracious, but never desperate. Marrow-deep, but never less than beguiling on its surface (how else to describe a movie whose protagonist is born in the 17th century, and finds themselves in bed with Billy Zane at the turn of the millennium?). Unlike Woolf’s novel, Potter’s version offers an explanation for why Orlando doesn’t age, but this strange and entrancing fable is the rare film that feels truly timeless. —DE

Rent or buy on Amazon.

71. “Wendy and Lucy” (Kelly Reichardt, 2008)

Field Guide/Film Science/Glass Eye/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

Kelly Reichardt’s work has always displayed a keen knack for the capturing the intimacies and heartbreaks of the working class, and while later works like “Certain Women” (a triptych story told with some remarkable actresses) and “Meek’s Cutoff” (Reichardt goes period, with startling results) continue in that tradition, nothing else is as deeply felt as her first collaboration with star Michelle Williams.

The Cannes premiere follows Williams as the eponymous Wendy, a young woman hoping for a better life and losing nearly everything — namely, her beloved dog Lucy — along the way. Reichardt never revels in the fear or shame of her characters, and her deep humanism only makes Wendy’s plight all the more compelling. The small-scale feature is big on emotion, and it subverts any uncomfortable sense of “poverty porn,” instead honing in on realism without judgement, finely crafted at every turn. —KE

Buy on Amazon.

70. “Pariah” (Dee Rees, 2011)

Chicken And Egg/Mbk/Northstar/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

This Brooklyn-set coming out film arrived ahead of its time, but as director Dee Rees’ career has flourished, her remarkable debut has been given its rightful due. Humming with the electricity of repressed sexuality finally unbridled, “Pariah” follows teenage Alike (Adepero Oduye) on a journey toward queerness and masculine gender expression. We witness Alike quietly change out of her baseball hat and t-shirt on the train home to Brooklyn, donning a girly sweater in order to calm her parents’ suspicions (Kim Wayans and Charles Parnell). We melt alongside her as she lights up with the first tingles of love, seeing herself as desirable for the first time through the sparkling eyes of Bina (Aasha Davis). Dripping in rich, saturated jewel tones that became de rigueur in the years that followed, “Pariah” pulses with the rhythm of first love and the cost of self-discovery. —JD

Rent or buy on Amazon.

69. “Portrait of Jason” (Shirley Clarke, 1967)

Shirley Clarke

A landmark non-fiction achievement, Shirley Clarke’s portrait centers on Jason Holliday (real name: Aaron Payne) – a flamboyant gay cabaret performer. Filmed over the course of one night at the Chelsea Hotel in New York City, Holliday dished on a myriad of topics — racism, homophobia, parental abuse, show business, drugs, sex, prostitution, the law, and more — as he told the story of his life. With each passing minute, he becomes increasingly intoxicated, and his revelations become increasingly raw, culminating in an emotionally vulnerable state. The result is a mesmerizing portrait of a complex man, who weaves tales that are collectively hilarious and heartbreaking. It’s a riveting, must-see “confessional” that the late great Ingmar Bergman called “the most extraordinary film I’ve seen in my life.” The transgressive work was restored and re-released in 2012. —TO

Rent or buy on Amazon.

68. “Cameraperson” (Kirsten Johnson, 2016)

Sundance

Kirsten Johnson opens “Cameraperson” with a note describing the project as “my memoir,” but it’s safe to say there’s never been a memoir quite like this one. Cobbling together footage from her 25 years of experience as a documentary cinematographer, “Cameraperson” offers a freewheeling overview of the people and places Johnson has captured over the course of a diverse career. More than that, the two dozen projects showcased here alongside original footage confront the process of creation.

This is a collage-like guide to a life of looking. And she has seen a lot: a birthing center in Nigeria, a detainment center for Al Qaeda prisoners, Michael Moore antics, and so much more. “Cameraperson” would be a riveting embodiment of life itself even if the filmmaker didn’t take the next step and personalize the material, but the footage of her Alzheimer’s-stricken mother gives the movie an additional poignance. “Cameraperson” is as much about the complexity of the world around us as it is an illustration of its universal fragility. —EK

Rent or buy on Amazon.

67. “Morvern Callar” (Lynne Ramsey, 2002)

Company/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

Picking a favorite Lynne Ramsay film is exceedingly difficult, even when accounting for the fact that she’s only made four features, but “Morvern Callar” stands out even among a one-of-a-kind filmography that began with “Ratcatcher” and took on new dimensions in last year’s “You Were Never Really Here.”

A never-better Samantha Morton (and that’s saying something) plays the title character, a young Scottish woman dealing with the aftermath of her boyfriend’s suicide — a transformative event that brings out a heretofore unseen side of herself as she passes off his unpublished novel as her own and goes on holiday in Spain. Ramsay and Morton ensure that it’s nowhere near as glamorous as that description might make it sound, of course, but “Morvern Callar” remains as intoxicating now as it was in 2002.—MN

Stream on Amazon.

66. “Girlfight” (Karyn Kusama, 2000)

Sony

Karyn Kusama’s 2000 debut would be worthy of celebration if its main accomplishment was presenting Michelle Rodriguez to the world for the first time, but this tough-as-nails depiction of a Brooklyn teen boxer matches her hardened screen presence with extraordinary energy and attitude.

A neorealist “Rocky,” the movie follows moody Diana Guzman from her high school skirmishes to the new outlet for her rage that she discovers at the gym. Forced to argue her way into the ring, Diana fights through an uneasy relationship with Adrian (Santiago Douglas), who also becomes her opponent in a climactic battle. Kusama’s jittery, naturalistic filmmaking style gets into the center of these showdowns with visceral intensity, and presents the battle of a young woman in a man’s world as the ultimate success story. Its ferocity still resonates nearly 20 years later. —EK

Buy on Amazon.

65. “A New Leaf” (Elaine May, 1971)

Paramount Pictures

Elaine May’s directorial debut should be frustrating and maybe even reprehensible. Instead, it’s charming and life-affirming. Walter Matthau plays a gentleman in the Old World Continental sense – he has money, so he doesn’t want to work. He wants to spend his life driving his sports car, ordering around his butler, and completely avoiding real-world practicalities. When it becomes clear he’s lost all his money, he decides to take a wealthy bride. He finds the perfect sap in a millionaire horticulturalist played by May.

He plans to marry her, then kill her and keep her money. He’s abominable — but, though still committed to his plan, he ends up defending her from all the parasitic individuals in her life who are bleeding her finances dry. At first it’s just so he can have the money for himself, but as he keeps protecting her from the villains in her life, he ends up, in fact, falling for her. She’s even more incapable of dealing with life than him, and in learning to defend her he’s developed the skills to actually deal with the world. It’s romance as self-actualization, the most romantic kind of film. Hilarious, sweet, and a little sad, it’s vintage Elaine May. —CB

Rent or buy on Amazon.

64. “Can You Ever Forgive Me?” (Marielle Heller, 2018)

M Cybulski/20thCenturyFox/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

Three years after breaking out with her indelible “The Diary of a Teenage Girl,” Marielle Heller returned to the big screen with the utterly charming true story “Can You Ever Forgive Me?” (co-written by fellow female filmmaker Nicole Holofcener, no less). The dramedy, based on the insane real-life exploits of author and forger Lee Israel, stars Melissa McCarthy as Lee and Richard E. Grant as her unlikely best pal (and literal partner in crime) Jack Hock.

The film is many things: a love letter to a bygone New York City, a story of a truly complex female character, a heist thriller, and a tale about the corrosive power of loneliness and failure. The stakes are both low-scale and of the utmost importance, because the only thing on the line is Lee’s livelihood — but Heller makes the case that it’s not just her job and finances on the line, it’s her very sense of self. What could possibly be more important? Bittersweet and funny and even a bit scary, it’s also true. —KE

Stream on Hulu via Cinemax; stream on Amazon via Cinemax; rent, or buy on Amazon.

63. “Real Women Have Curves” (Patricia Cardoso, 2002)

HBO

Patricia Cardoso’s Sundance-winning “Real Women Have Curves” is a crowd pleaser in the best sense of the word. The film stars then-discovery America Ferrera as an 18 year old caught in the middle of tradition (staying in Los Angeles to work at a sewing factory and provide for her family) and her own personal ambitions (leaving Los Angeles for college in New York City). Cardoso’s relaxed directing style invites the viewer to explore the film’s Latin American culture and themes with open arms, and its messages of family and self-love are never handled in didactic terms. Every character rings true (especially Lupe Ontiveros as the family matriarch) and makes a traditional narrative pop with irresistible authenticity. —ZS

Stream on Hulu via HBO Max; stream on Amazon via HBO; buy on Amazon.

62. “Bend It Like Beckham” (Gurinder Chadha, 2003)

Bend It/Film Council/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

David Beckham is no longer the soccer star du jour, having long since been eclipsed by Messi and Ronaldo, but “Bend It Like Beckham” remains as warm and uplifting as it was when Becks was scoring goals at Old Trafford. Directed by Gurinder Chadha (whose earlier “Bhaji on the Beach” is also worth seeking out and who just scored a huge Sundance hit with “Blinded by the Light”), it goes beyond the pitch as it delves into the plight of Punjabi Sikhs in England and other issues of the day — all while maintaining a loose spirit that keeps it firmly in the feel-good realm. Parminder Nagra and Keira Knightley are great teammates and even better castmates, keeping things fleet of foot even as they and their director ensure that “Bend It Like Beckham” is never a mere trifle. Chadha, who grew up in London as part of the Indian diaspora, finds both pain and beauty in her heroine’s attempt to please her traditional parents while forging her own duel identity.—MN

Stream on Disney+; rent or buy on Amazon.

61. “Reassemblage” (Trinh T. Minh-ha, 1983)

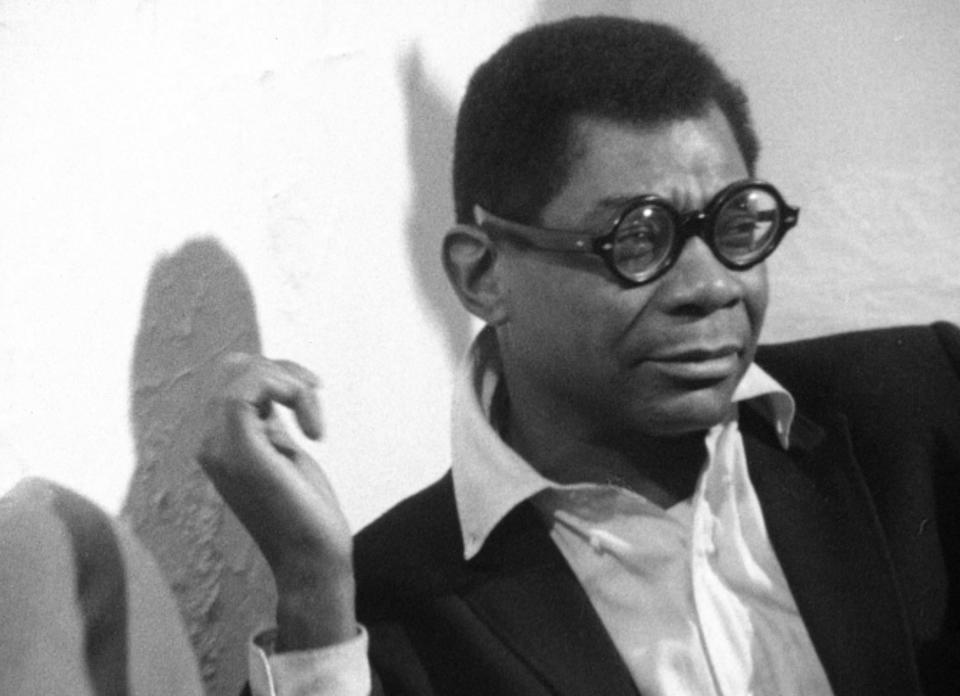

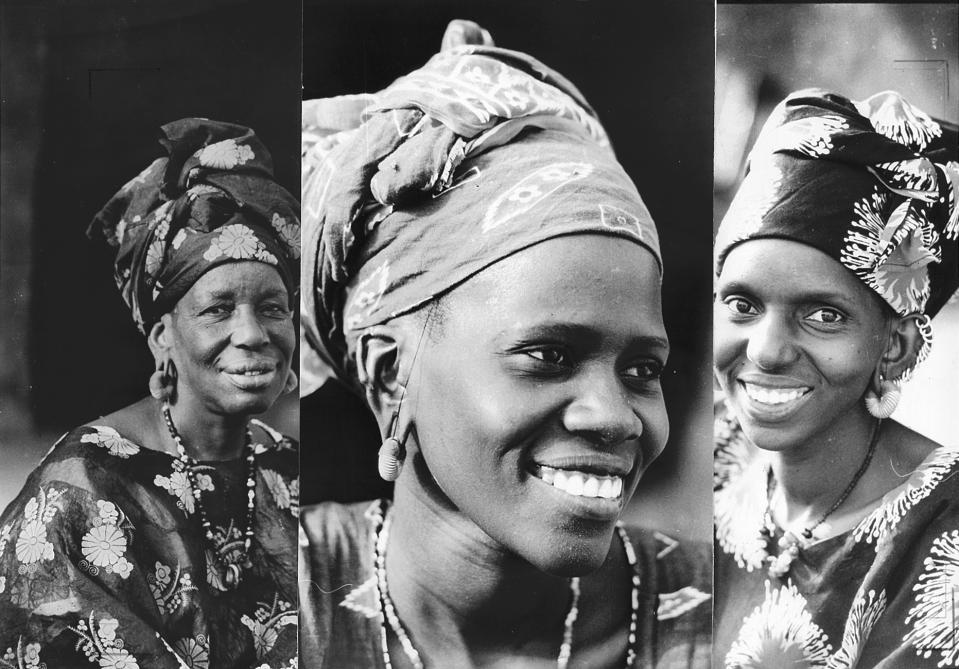

Trinh T. Minh-ha

Trinh T. Minh-ha’s first film is a thorny visual essay on women of rural Senegal. Shunning more conventional ethnographic documentary tropes, the film captures scenes about the daily life of its subjects, waiving the use of an expected narration, as the women themselves tell their own stories. Additionally, the filmmaker foregoes the long takes typical of observational style filmmaking, and at times completely extricates sound from image, for what, as its title suggests, is a more disjointed construction.

For Trinh, who is Vietnamese, it was important to avoid the othering and exoticization that often plagues ethnographic cinema. In that sense, playing with the attributes of a certain kind of filmmaking, “Reassemblage” doubly functions as a work of film criticism itself, critiquing both western biases and documentary convention. Audiences are also challenged by what is ultimately a rather stimulating experiment that demands multiple viewings. —TO

60. “Big” (Penny Marshall, 1988)

Brian Hamill/20th Century Fox/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

Penny Marshall left an unparalleled legacy when she passed away late last year, coming to fame on “Laverne & Shirley” before embarking on a second act behind the camera for which we’re all the better. “Big” was the first film directed by a woman to gross more than $100 million at the box office (it eventually topped out at $151.7 million), making it as important to Hollywood decision-makers as it was to so many viewers’ childhoods. Anyone who can resist the sight of Tom Hanks and Robert Loggia on the walking piano at FAO Schwarz deserves a grim fortune from Zoltar, not that Marshall would allow such an outcome — as “Big” showed us, she was too kind a filmmaker to give viewers anything but a happy ending. —MN

Rent or buy on Amazon.

59. “My Brilliant Career” (Gillian Armstrong, 1979)

Melbourne filmmaker Gillian Armstrong launched her long feature directing career (“High Tide,” “Mrs. Soffel,” “Little Women”) with gorgeous feminist drama “My Brilliant Career,” which played in Competition at Cannes and the New York Film Festival. Based on Miles Franklin’s turn-of-the-century classic and nominated for a Best Costume Design Oscar, the movie broke out Judy Davis, who won the Best Actress BAFTA for playing scrappy aspiring writer Sybylla Melvyn, who turns down her two suitors (who could spurn the young Sam Neill?) in order to hang onto her independence in New South Wales. “I make no apology for being egotistical,” she declares, “because I am!” —AT

Buy on Amazon.

58. Zora Neale Hurston’s Early Ethnographic Films (1920s-30s)

Shutterstock

Beginning in the 1920s, Zora Neale Hurston developed fluency in several fields, including filmmaking, where she played a pioneering role, arguably becoming the first African-American woman filmmaker. On an expedition to perform ethnographic research in the rural south in 1928, Hurston shot over a dozen reels of films, as a method of preserving the heritage of African-American culture in the south. Of the reels that survived is grainy black-and-white footage capturing children at play (“Children’s Games,” 1928), a baptism in a river (“Baptism,” 1929), a logging camp (“Logging,” 1928), and footage of octogenarian Cudjo Lewis, the final survivor from The Clotilde, the last arriving slave ship to America (in 1859) — also the subject of Hurston’s “Barracoon,” which was published 87 years after it was written. The clips are without intertitles, although there is musical accompaniment comprised of spirituals and bluegrass music. Considered fundamental works of visual anthropology, Hurston’s films provide very rare examples of the everyday lives of ordinary black people in the South during the era. —TO

57. “Little Women” (Gillian Armstrong, 1994)

Joseph Lederer/Di Novi/Columbia/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

Louisa May Alcott’s 1868 novel has long been popular cinema fodder (Greta Gerwig is directing a sixth adaptation, which will be out in 2019), but it’s the meticulously-crafted fifth iteration that has become a classic. Directed by Gillian Armstrong and featuring an all-star cast that included Winona Ryder, Claire Danes, Susan Sarandon, Kirsten Dunst, and Christian Bale, to name a few, the 1994 drama tells the story of the March sisters: beautiful Meg, tempestuous Jo, kindhearted Beth, and amorous Amy, who are growing up in Concord, Massachusetts, during and after the American Civil War. With their father away fighting in the war, the girls struggle under the guidance of their strong-willed mother, Marmee. As the sisters’ external obligations clash with their personal desires, what is an otherwise charming children’s tale is upgraded to a centerpiece of feminist cinema. —TO

Stream, rent, or buy on Amazon.

56. “Girlhood” (Celine Sciama, 2014)

Pyramide Distribution

Céline Sciamma’s “Girlhood” is, hands down, one of the best coming-of-age movies of the decade. The film stars Karidja Touré as a young woman who joins a girl gang outside of Paris in order to escape her toxic personal life. The group gives her a sense of self-worth, and it’s in the near-Hitchcockian way Sciamma visualizes her character’s growth that “Girlhood” gets its power. Sciamma marks each new transition in the character’s behavior with a telling fade to black, tracking her emerging consciousness in bursts of interconnected experiences that avoid forcing her to process it into a single tidy narrative. The steady progression of images, from the girl pocketing a knife from her family kitchen to, several scenes later, joining her gang in sing-a-long to Rihanna’s “Diamonds,” evocatively convey a traditional character arc in fresh and exciting terms. —ZS

Rent or buy on Amazon.

55. “You Were Never Really Here” (Lynne Ramsay, 2018)

Alison Cohen Rosa | Amazon Studios

Lynne Ramsay’s remarkable “You Were Never Really Here” is a postmodern action film that serves as both a character study on the psychological toll violence takes on a person and a litmus test for the viewer’s own craving for violence in action cinema. A never-better Joaquin Phoenix stars as a war veteran suffering from PTSD who is assigned to rescue a young girl from a high-end prostitution ring. The mission allows Ramsay to meditate on the nature of violence. Her challenging directorial choices eliminate graphic violence in order to heighten Joe and the viewer’s emotional torture. “You Were Never Really Here” runs 89 minutes and is hardly grotesque, and yet most viewers leave thinking they’ve watched one of the most violent films of the decade. Through editing and suggestion, Ramsay leaves you floored. —ZS

Stream on Amazon.

54. “The Savages” (Tamara Jenkins, 2007)

Fox Searchlight Pictures

Tamara Jenkins has directed only three features in two decades, but each made its mark and left audiences wishing for more. As talented an original (and solo) screenplay writer as director of her three features (the others are “Slums of Beverly Hills” and last year’s “Private Life”), “The Savages” illustrated her ability to capture corners of family life that resonate with perceptiveness and originality. Here, she united the complications that arise when two strong-willed, long-separated siblings are forced by parental care issues to find common ground. She also scored near-career best performances from both Laura Linney (who along with the script was an Oscar nominee) and Philip Seymour Hoffman. One of the hallmarks of Jenkins’ work is that, while she has kept to contemporary domestic narratives, she has delved into distinct situations and relationships, discovering truths in each of them that go beyond many of the cliches in similar stories. —TB

Rent or buy on Amazon.

53. “Paris Is Burning” (Jennie Livingston, 1990)

Off White Prod/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

Jennie Livingston’s smash hit documentary has weathered a storm of criticism and controversy over the years, but its legacy remains stubbornly intact. Filmed in the mid-to-late 1980s and released in 1990, the film introduced the drag queens and transgender women who populated New York City’s drag-ball scene to the culture at large, forever altering its fabric. Serving executive realness while dressed to the nines, the subjects of Livingston’s film are larger than life and vibrating on their own electric frequencies. At the time, the film was praised for addressing intersecting issues of race, class, and sexuality, but Livingston’s whiteness eventually became problematic for many critics of film history.

The subject has been taken up by feminist thinkers such as bell hooks to Judith Butler, even as the film was added to the National Film Registry in 2016. Ball culture and its undeniable power to ignite the screen have inspired other projects, including 2016’s “Kiki” and the FX series “Pose,” but the enduring power of “Paris Is Burning” ensures that these are always in conversation with this foundational work. —JD

Buy on Amazon.

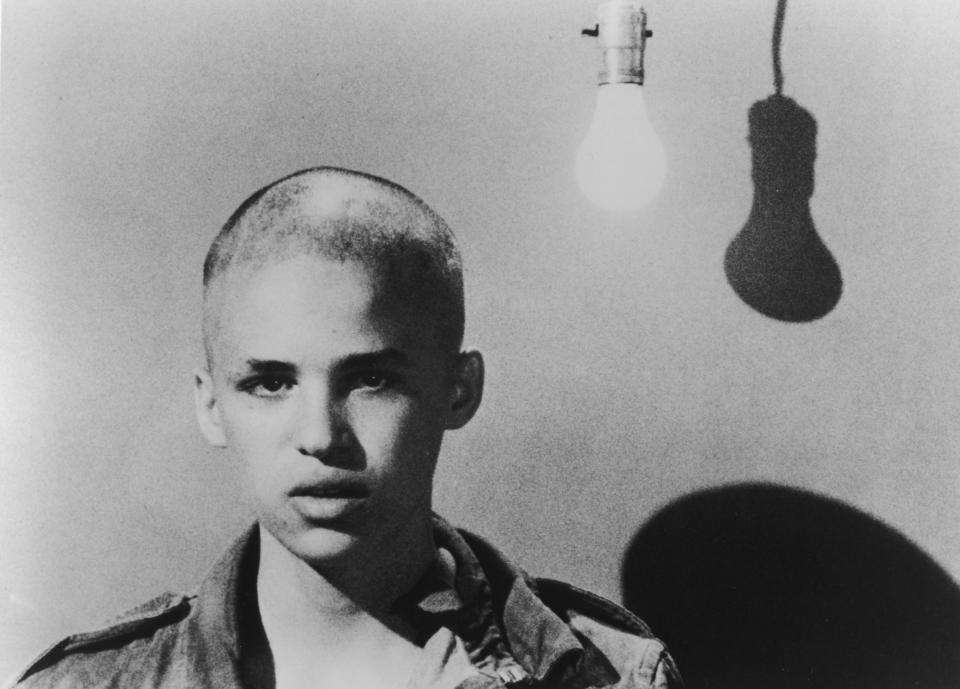

52. “Breathe” (Mélanie Laurent, 2014)

Shutterstock

From her film’s turbulent first scene to its De Palma-level long-take and the shocking finale that follows, the multi-talented Mélanie Laurent shot the utter hell out of her second feature. A shrewd thriller about teenage insecurities, psychosexual violence, and the general turbulence of growing up, “Breathe” tells a twisted story of female friendship with the nuance and know-how of someone who still remembers what it feels like to be suffocated by teenage thirsts. There’s something indivisibly intimate and elemental about the bond that forms between a mousy child of divorce (Joséphine Japy) and the mysterious new girl at school (an unforgettable Lou de Laage), and something just as true about the terrible ways in which it tears apart. Does passion set people free, or are people imprisoned by their desires? It’s a hard question to answer, but few movies have ever asked it with such relish. —DE

Stream, rent, or buy on Amazon.

51. “Mabel’s Blunder” (Mabel Normand, 1914)

Mabel Normand, from the start, defied the idealized femininity seen in D.W. Griffith’s pure-as-the-driven snow heroines, or fragile beauty portrayed in the “Gibson Girl” portraits of the time. She was the pie-throwing, athletic, devious, endlessly inventive ring leader of Mack Sennett’s chaotic Keystone slapstick troupe. Keystone was, in part, built on the spirit of Normand, so it made sense that Sennett allowed Normand to start making her own films – especially when the alternative likely was losing her (and he eventually did), like he did Chaplin and Arbuckle, to the larger studios. The shift in the director’s chair resulted in Normand’s films just becoming more Mabel, including being seen more directly from her character’s perspective. With “Mabel’s Blunder,” Normand takes a mistaken identity premise and drives it off the cliff into a gender-bending delight. In the hands of Normand, the farce became a freedom that shattered society’s shackles. –CO

50. “Sink or Swim” (Su Friedrich, 1990)

Su Friedrich via YouTube screenshot

Since Maya Deren established an alternative film language in the 1940s with “Meshes of the Afternoon,” “Ritual in Transfigured Time,” and other films that mixed formalist experiment with ethnography, women have been among the most important drivers of American avant-garde and experimental cinema: Marie Menken, with her mastery of immersive sound; Carolee Schneemann, with her daring excursions into sexuality and symbolism; Gunvor Nelson, with bold exercises in repetition like “My Name Is Oona”; Michelle Citron, who pioneered a kind of diary cinema to express feminist concerns; and Su Friedrich, who built off their work and pushed the avant-garde in even more provocative directions.

Friedrich’s “Sink or Swim” is an impressionistic 48-minute inquiry into the inescapability of memory: it’s a collection of 26 short stories, each given a title like “Virginity” or “Pedagogy,” related in voiceover (and in the third person) by a young girl about incidents from her childhood and all juxtaposed with seemingly unrelated but symbolically significant imagery: a story about the childhood discovery of a book of Greek mythology is set against images of female bodybuilders going through poses; she relates the experience of seeing a film version of “The Time Machine” and what it says about humanity’s devolution while the camera sits on the front of a wooden roller-coaster car and films the entirety of the ride.

“Covering her eyes, she begged to leave the theater. Her father reached over, pulled the hands from her face, and insisted she watch the rest of the movie.” Those kind of moments stick with you forever and can sneak up on you in the most unlikely settings – even when on a rollercoaster. The genius of Friedrich’s film is that its memories come to feel like your own. —CB

Stream on Amazon via Fandor.

49. “The Hurt Locker” (Kathryn Bigelow, 2009)

Summit Entertainment

The first entry in the most exciting period of Kathryn Bigelow’s career finds her transforming the experiences of a bomb detonation unit in Iraq into a remarkable feat of suspenseful filmmaking. Bigelow broke the Academy’s glass ceiling by becoming the first (and so far only) woman to win an Oscar for best directing, but no one could argue that a progressive agenda pushed her to the top; the accomplishment stems from the sheer brilliance of her direction, as she takes the familiar circumstances of straight-faced men risking their lives in dreary, dusty landscapes and turning that risk into a deeply involving experience.

The gut-punch of the finale suggests that, for a select few in the heat of the action, the intensity of risking one’s life for dubious reasons is an addictive drug. It’s an astonishing slow-burn thriller with real ideas. Mark Boal’s journalistic screenplay gives each scene an undercurrent of realism that cuts deep, but “Hurt Locker” is especially gratifying for the way it consolidates decades of Bigelow’s filmmaking mastery even while pushing it in a fresh direction. —EK

Stream on Hulu; stream, rent, or buy on Amazon.

48. “The Decline of Western Civilization” (Penelope Spheeris, 1981)

Spheeris Inc/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

The image of W.A.S.P. guitarist Chris Holmes drinking vodka in a pool, feet away from his aghast mother, may be the most indelible from Penelope Spheeris’ “The Decline of Western Civilization” trilogy, but it’s far from the only one. The 1981 original chronicles the punk-rock scene in L.A. circa 1980, when bands like X and Black Flag were making a name for themselves in the underground — and, thanks to Spheeris, beyond. A mosh pit of a documentary, it’s as raw and unadorned as the music; functioning as a concert film in one scene, a behind-the-scenes exposé in the next, and a portrait of disaffected 20-somethings in another, “The Decline of Western Civilization” is also an essential time capsule. The Library of Congress would appear to agree, as it selected Spheeris’ film for preservation in the National Film Registry three years ago. —MN

Stream, rent, or buy on Amazon.

47. “The House Is Black” (Forough Farrokhzad, 1963)

Forough Farrokhzad

Forough Farrokhzad was only 27 years old when she made this poetic 22-minute documentary about an Iranian leper colony. She displays a radical empathy in her engagement of her subjects, who she shows going about daily tasks, receiving treatment, and attending school. The title comes from a sentence a young student suffering leprosy writes across a blackboard. Throughout, sayings from the Koran and the Old Testament are spoken as voiceover – as are some of Farrokhzad’s own poems. She’s best known for her poetry, which provide a unique window into a woman’s life in mid-century Iran and transcendent glimpses beyond. This one film of hers is so beautiful, so poetic that it does come close to aestheticizing suffering, but Farrokhzad showed her empathy was not for show — the making of this film greatly affected her and she adopted a young boy featured in it. Tragically, Farrokhzad died at age 32 in a car accident. —CB

Buy on Amazon.

46. “Mikey and Nicky” (Elaine May, 1976)

Criterion Channel

Peter Falk and John Cassavetes in front of the camera, Elaine May behind it — really, what more can you ask for? A two-time Oscar nominee for writing “Heaven Can Wait” and “Primary Colors,” May was truly on a roll in the 1970s: “Mikey and Nicky” was preceded by “A New Leaf” (which she wrote, directed, and starred in) and “The Heartbreak Kid,” and followed immediately by “Heaven Can Wait.” In this, a two-hander for the ages, Mikey (Falk) is constantly bailing Nicky (Cassavetes) out of his trouble and struggling to figure out how seriously he should take his best friend’s repeated insistence that “they’re gonna kill me.” It never quite got its due, but that may be beginning to change: The Criterion Channel recently gave it pride of place as the new streaming service’s inaugural Movie of the Week.—MN

Buy on Amazon.

45. “The Hitch-hiker” (Ida Lupino, 1953)

Alamo Drafthouse

Ida Lupino was the first mainstream American female filmmaker to make movies within the Hollywood studio system in the 1950s. “The Hitch-hiker” is her crowning achievement, a film noir that daringly rewrites the visual style of the genre and injects it with the frightening suspense of the serial killer movie. Lupino also served as co-writer, using the real American killing spree by Billy Cook as the basis for her story about two fishermen who pick up an escaped convict. Lupino shot on location in the Alabama Hills of California and uses the contrast between the car’s claustrophobic interior and the vastness of her location to create an uneasy push and pull that gives every moment an effective sense of dread and suspense. For as much of a breakthrough as Lupino was to the history of female directors, so too was “The Hitch-hiker” for film noir. —ZS

Stream, rent, or buy on Amazon.

44. “Stories We Tell” (Sarah Polley, 2012)

Moviestore/REX/Shutterstock

Sarah Polley tries to piece together a family secret surrounding her deceased mother, and the narrative the family has crafted to mask themselves from the truth, which could have a profound affect on the filmmaker’s identity. Polley’s generosity of spirit is beautiful. Her ability to structure and create a film that embodies that spirit is remarkable – a piece of filmmaking worthy of a Renoir-of-nonfiction comparison. The result is a frank, tender family portrait that uses cinema to capture the emotional fuzziness of memory — which, if it wasn’t for the deeply personal nature of the story, would be the ideal meditation on the nature of images themselves. A perfect film. —CO

Stream on Amazon.

43. “The Watermelon Woman” (Cheryl Dunye, 1996)

Metrograph

In 1996, there were only so many images of black women onscreen, not to mention black queer women. Which is exactly why, when Cheryl Dunye cast herself as a documentarian in her feature debut, this clever meta-theatrical device added another layer to what still would have been a charming micro-budget love story. Set in Philadelphia, the character Cheryl becomes obsessed with learning about a mysterious and beautiful black actress from the 1930s, whom she dubs The Watermelon Woman. In yet another meta-layer, Dunye worked with lesbian artist Zoe Leonard to invent The Watermelon Woman, since she couldn’t find a black actresses from the era. The oh-so-90s-it-hurts aesthetic extends to Cheryl’s plum job as a video store clerk, where she picks up Diana (Guinevere Turner) and takes dating advice from her hilarious butch buddy, Tamara (Valarie Walker). With cameos from Camille Paglia, Toshi Reagon, and Sarah Schulman, the movie is a feminist lesbian wet dream, and a pioneering model of an underrepresented artist making the film she wanted to see in the world.—JD

Stream on Amazon via Fandor.

42. “The Virgin Suicides” (Sofia Coppola, 1999)

American Zoetrope/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock