14 peace anthems and the stories behind them

Most of us could use more peace in our lives. Whether it’s ongoing conflict across the world we’re considering, or the many little wars we fight on a daily basis – with each other, with ourselves – it’s not difficult to see how fraught the modern age can feel.

Our battles are different in nature to those of bygone generations, and in a lot of ways they’re more complicated. More insidious. Horrors, issues and disagreements that get under our skin. Music can hold a mirror up to this. Historically, the ‘protest song’ tends to get more airtime.

Heavy music in its politically inclined forms (from early blues and folk to punk and metal) has often taken an oppositional approach: identifying wrong and rallying against it; calling listeners to arms; or just providing an outlet for anger. Some of the most powerful statements in music have stemmed from such sources, from Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit to Rage Against The Machine’s Killing In The Name.

But in this age of information (and, increasingly, misinformation), perhaps a call for acceptance is just as useful? And, for that matter, aren’t some of the greatest ‘protest songs’ (for example Edwin Starr’s immortal War) really pacifist anthems at heart? We highlight some of the finest peace songs recorded, from soul stars to hard rockers and beyond, from the 1940s to the present day.

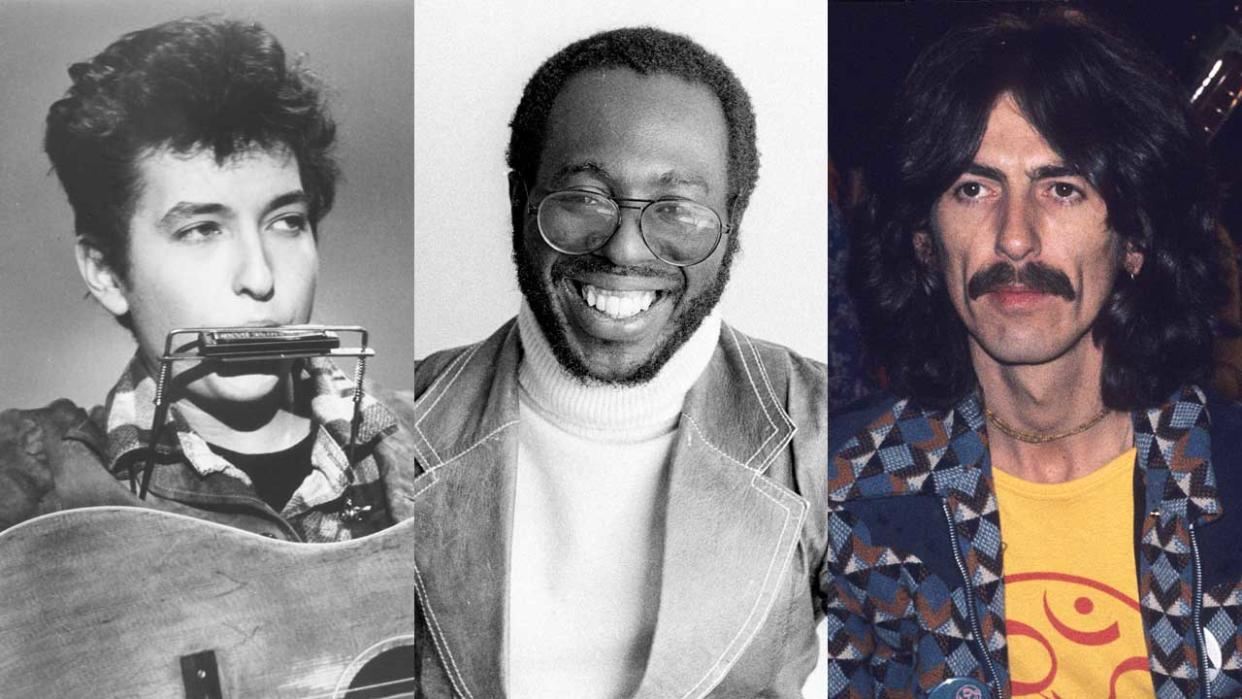

George Harrison Give Me Love (Give Me Peace On Earth)

George Harrison’s spiritual antennae was raised high in his earliest post-Beatles years, with the guitarist announcing an ambition to be “God-conscious”, and 1973’s Give Me Love (Give Me Peace On Earth) flowing from him as though written by a higher power.

“Sometimes you open your mouth and you don’t know what you are going to say, and whatever comes out is the starting point,” he wrote in his 1980 autobiography I, Me, Mine. “This song is a prayer and personal statement between me, the Lord, and whoever likes it.”

Give Me Love was no act of remote handwringing from a grief-tourist rock star. Harrison knew all about the human cost of conflict, having recently waded into the Bangladesh Liberation War with his famous New York benefit shows of ’71. Yet where a Bruce Springsteen or a Neil Young might have bitten harder, Harrison’s song painted a soundscape that sounded like peace already achieved, with a benevolent acoustic strum joined by a slide riff evoking a Honolulu sunset. The only possible note of conflict was the fact that Give Me Love knocked Wings’ My Love off the top of the US singles chart.

Sam Cooke - A Change Is Gonna Come

One of the most influential voices in soul, Sam Cooke brought gospel music to the masses in 50s America before becoming a superstar of pop-R&B with sweet songs such as You Send Me and Cupid. Cooke was working in a time of the Jim Crow segregation laws, one of many successful black artists unwelcome in white-only spaces around the US.

The night that Cooke, his wife and his entourage were told by a Louisiana hotel that there were no vacancies – even though they’d pre-booked – became musical grist, with Bob Dylan’s Blowin’ In The Wind as a touchstone. Cooke went back to his musical roots for the deeply moving A Change Is Gonna Come.

“When he came out with that song we needed black people to do something for black people, and Sam Cooke was at the top,” Mavis Staples told CBS News on the single’s 50th anniversary in 2014. Cooke died tragically two weeks before its release in December 1964, but the song gained popularity with the thriving equal rights movement and was referenced by Barack Obama on the night of his 2008 presidential election.

Buffalo Springfield - For What It’s Worth (Stop, Hey, What’s That Sound)

Buffalo Springfield guitarist Stephen Stills’s military background laid the foundation for this December 1966 release. Moving around between North, South and Central Americas, Stills and his father witnessed oppression and violence, surrounded by gunshots during experiences that Stills would later reflect on as a young musician living in LA.

In the mid-60s a different kind of oppression loomed there; his countercultural brethren in the city were barred from visiting the clubs and music venues of Sunset Strip because they caused “traffic congestion” and their presence was “bad for business”. Curfews were applied, and small groups of out-late hippie revellers would be piled on by busloads of law enforcement. A peaceful demonstration against the measures led to clashes with the LAPD.

The moment captured in song, Neil Young’s two-note guitar signature rang out as Stills’s cool, jazzy observation called for calm and rationality in the face of fear and paranoia. ‘Young people speaking their minds, getting so much resistance from behind’ would soon translate to Vietnam War dissent and beyond, and For What It’s Worth became one of the most covered and quoted peace songs of all time.

Lenny Kravitz - We Want Peace

Perhaps there was more substance than styling behind Lenny Kravitz’s peace-shaman vibe: he had been named after an uncle killed in the Korean War, and was already calling for tolerance on his 1989 debut album (tellingly titled Let Love Rule) and through his involvement with the 1991 Peace Choir protests against the Gulf War.

“Writing songs about unity, about God and about change has always been a part of me,” he said. Kravitz would release better-known peace songs (‘So tell me why we got to die, and kill each other one by one,’ demanded Are You Gonna Go My Way, his biggest hit). But for connoisseurs, We Want Peace remains a lost gem, released in 2003 as a download-only single in protest at the US invasion of Iraq.

The track is now unavailable on Spotify, and therefore largely forgotten. Which is a shame. With its choppy dirty-soul guitar, an instantly catchy gang-chant lyric that left nothing to metaphor (‘We want peace, we want it, yes!’) and a haunting contribution from Iraqi singer Kadim Al Sahir that evoked a mullah calling the faithful to prayer, We Want Peace could have been a high point in the Kravitz catalogue.

The Byrds - Turn! Turn! Turn!

Without the tumble of harmonies and the crystalline cascade of Roger McGuinn’s 12-string Rickenbacker, The Byrds’ 1965 single Turn! Turn! Turn! would surely never have scaled the Billboard chart and become a classic. But by their own admission, the West Coast band had stood on the shoulders of giants to record it.

Six years before, the folk singer Pete Seeger had nominally written the song (in truth, even his credit was hanging on by its fingernails, as the lyric was taken almost word-for-word from the Book Of Ecclesiastes). But while Seeger’s lyrical contributions were mostly limited to punctuating the Bible text with ‘turn, turn, turn’, one addition made a powerful impression: ‘A time for peace… I swear it’s not too late’.

With The Byrds at the microphone, it was that final line that resonated, concluding a song that is as close to a bottling of the 60s zeitgeist as exists on record. In that same spirit of harmony, Seeger wrote a letter to express his thanks. As The Byrds’ David Crosby remembered: “It said: ‘You know, they used to do everything but burn crosses on my lawn for being a communist. Now they come around and ask for my autograph.’”

Bryan Adams - What If There Were No Sides At All

Released in May 2023, Bryan Adams’s musical call for peace sadly wasn’t short of material – not least the ongoing war in Ukraine. Co-written by Adams and Nashville songwriter Gretchen Peters, it acts as an umbrella for the myriad conflicts across the world, rather than homing in on one in particular. The result is one of his most potent songs of recent times, with one foot in the gauzy popscapes of The Beatles and the other in the feeling of lostness caused by divided times. It’s a heartfelt plea for understanding and tolerance, framed in a dreamy yet searing pop song.

“This is an anti-war peace song written with the aim to provoke thought and perhaps even encourage governments to sit down and talk peace,” Adams says. “At the moment, there is only escalating division and death – a result of the billions of dollars spent by governments to fund these endless wars, not just in Ukraine but around the world. Why?” Some 52 years on from John Lennon’s Imagine, it’s tragic that such familiar sentiments are still so prescient

Scorpions - Wind Of Change

Although it is often associated with the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall, this towering ballad was inspired by the Scorpions’ first tour of the Soviet Union a year earlier. “We wanted to show the people in Russia that here is a new generation of Germans, and they’re not coming with tanks and guns, they’re coming with guitars and rock’n’roll, bringing love,” guitarist Rudolph Schenker said.

Despite those good intentions, Moscow officials cancelled the band’s dates in their city, due to fear that it might provoke riots. But when the Scorpions returned a year later, they performed in front of a huge crowd of 300,000 people at the Moscow Music Peace Festival, and the country’s new mood of glasnost spurred singer Klaus Meine to write Wind Of Change.

The whistling intro – a poetic way to say that change begins with one person – opens up to a melody as soaring and inclusive as a national anthem. The band’s highest-charting single, it still holds the record for best-selling single by a German artist. When the Scorpions perform it now, the lyric has been changed to: ‘Now listen to my heart, it says Ukraine, waiting for the wind to change.'

Creedence Clearwater Revival - Fortunate Son

In the late 60s, as he watched a generation of working-class Americans return from Vietnam in boxes draped with the Stars and Stripes, John Fogerty sat with a guitar and questioned why some kids were able to duck the conflict, while others were destined to be cannon fodder.

“The thoughts behind Fortunate Son, it was a lot of anger,” he said in 2015. “So it was the Vietnam War going on. Now, I was drafted and they’re making me fight, and no one has actually defined why. So this was all boiling inside of me and out came ‘It ain’t me, it ain’t me, I ain’t no senator’s son.’”

By never specifying Vietnam in the lyric, the CCR track has echoed through the ages, soundtracking the pushback against rolling generations of military conflict. Except Donald Trump didn’t get the subtext, and used the song at a 2020 rally despite his own draft deferment. “He’s absolutely that person I wrote the song about,” noted a bemused Fogerty, and issued a cease-and-desist letter.

Curtis Mayfield - We Got To Have Peace

Looking up to his hero Sam Cooke, budding Chicago singer-songwriter-guitarist Curtis Mayfield also started out on the 50s gospel scene. As he and his group The Impressions moved through the 60s, his songs such as People Get Ready and Move On Up soundtracked US civil rights and Black Pride.

By 1968, Mayfield and his manager created their own record label, Curtom and Mayfield had allied with the Black Panther Party, which encouraged self-governance and liberation for African-Americans. His son Todd told Reverb: “Curtom made him a titan. He’d done what a black man in America wasn’t supposed to do – snatched control from a system designed to subjugate him.”

Mayfield’s songwriting could have political bite or be as tender as his graceful falsetto. His upbeat 1971 track We Got To Have Peace continued the narrative that had inspired Bob Marley: ‘And the people in the neighbourhood, who would if they only could/Meet and shake the other’s hand, work together for the good of the land.’ Peace was for everyone, and to ‘save the children’, for future generations.

John Lennon - Imagine

A half-century on from its initial release, it’s arguable that Lennon’s Imagine has been blunted by overexposure. But whether you played this soft-focus ballad in ’71, as the doomed Vietnam War neared its bloody endgame, or right now, as Russian military boots tramp through Ukraine, you can’t deny that Lennon’s vision is something to reach for: a borderless world without violence, famine, material greed or organised religion, underpinned by the knowledge that today is all we have.

One assumes the Beatles-era snark would have torn Imagine to shreds, but solo-period Lennon was growing fast through his association with Yoko Ono. Indeed, he admitted he would have credited her 1964 conceptual art book Grapefruit as a core inspiration, were it not for a mean streak of machismo: “In those days I was more selfish and I sort of omitted her contribution, but it was right out of Grapefruit.”

Bob Dylan - Blowin’ In The Wind

On the third track on Dylan’s 1963 album The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, the young songwriter squared up to the Masters Of War, practically pledging to throw the dirt down onto their coffins himself. But Blowin’ In The Wind, the opener of his second album, was less a viperous protest song, more a note of contemplative disbelief that the world’s brightest minds couldn’t see the cost of war.

As Dylan noted upon the song’s release: “I’m only twenty-one years old and I know that there’s been too many wars.” Dylan couldn’t – and didn’t – claim sole authorship of the song that died in the chart upon release but has come to be seen as his defining moment (“I took it off a song called No More Auction Block,” he said. “That’s a spiritual and Blowin’ In The Wind follows the same feeling”).

But ultimately the simple strum was secondary, serving as a framework on which to hang a series of impossible questions (‘How many times must the cannonballs fly, before they’re forever banned?’) to which the answer was always a feather on the breeze, spinning forever out of reach.

Dub Pistols feat. Rhoda Dakar - Stand Together

South London duo Barry Ashworth and Jason O’Bryan met in the mid-to-late 90s when frontman Ashworth would DJ parties and clubs “making a right fucking racket”, jamming with musicians. Since then the Dub Pistols’ MO was to bring block-rockin’ big beats to the worlds of rocksteady, ska and jungle. Alongside The Prodigy, Dub Pistols brought punk ’tude to dance music, often inviting heroes from 2-Tone and Trojan records, such as The Specials and Horace Andy, to join their rambunctious ranks.

At the tail-end of the 2010s, O’Bryan and Ashworth recorded a backing track and sent it to former Bodysnatchers frontwoman Rhoda Dakar. Dakar wrote the lyrics and recorded the vocal for this “message of unity”, Stand Together, which was scheduled for release in June 2020.

No one would have predicted a global pandemic, let alone an activism uprising following the murder of George Floyd in the US that summer. Accordingly Stand Together became even more significant as a head-bobbing, horn-section-boosted cry for us to deal with racism, intolerance and cultural polarisation as one: ‘It’s our intent to right wrong, we’ll stand together’.

Woody Guthrie - This Land Is Your Land

Borrowing a childlike Carter Family melody, the version of This Land Is Your Land released in 1945 deceived at first glance as a benevolent acoustic strum. But it had started as something far fierier. In 1940, riled by Irving Berlin’s blindly patriotic God Bless America (sung by Kate Smith), Guthrie had written This Land Is Your Land as a barbed retort, titling his first draft God Blessed America For Me, and with early verses that would have changed its atmosphere entirely.

One proposed couplet attacked the haves from the standpoint of a have-not (‘There was a big high wall there that tried to stop me/The sign was painted, said Private Property’), while a second punctured the American dream (‘By the relief office I saw my people, as they stood hungry’).

Guthrie ultimately dropped both of those early-draft verses, but perhaps the song functioned better as a thing of beauty, ensuring that it travelled further and mobilised future generations of firebrands. “This song was originally written as an angry song,” Bruce Springsteen once said before covering it live. “But this is just about one of the most beautiful songs ever written.

Cat Stevens - Peace Train

In 1971, folk-fusion troubadour Cat Stevens (now Yusuf, after his conversion to Islam in 1977) followed up Tea For The Tillerman, his most successful album to date, with the even bigger international smash Teaser And The Firecat. Moonshadow and his version of the Christian hymn Morning Has Broken brought him hits, but at the end of Teaser And The Firecat sits Yusuf’s defining message of hope, Peace Train.

Rolling Stone enthused at the time about the vivacious track, saying: “Peace Train has a healthy dose of Cat’s characteristic calypso funk, but what puts you through the windshield those first few times is all that hand-clapping and bass-drum pedal.”

All true. But also dig the gorgeous strings and delicate guitar playing that fades out as we jump on board, bound for a (hopefully) better world. Significantly, after the 9/11 terrorist attack, Yusuf – who had stepped back from public life for over 20 years – performed by video link an a-cappella version of Peace Train for a victims’ support charity show in New York, making his feelings known that those responsible were not following the principles of Islam.

“Peace begins in the playground,” Yusuf later stated. And following his work as a UNICEF/children’s charity activist since the 70s, a children’s book called Peace Train was published to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the track. Meanwhile, in 2020 the Yusuf Islam Foundation was set up, and his division aiming to relieve hunger, nurture education and cultivate respect across all borders was named Peace Train.