15 essential Robbie Robertson songs

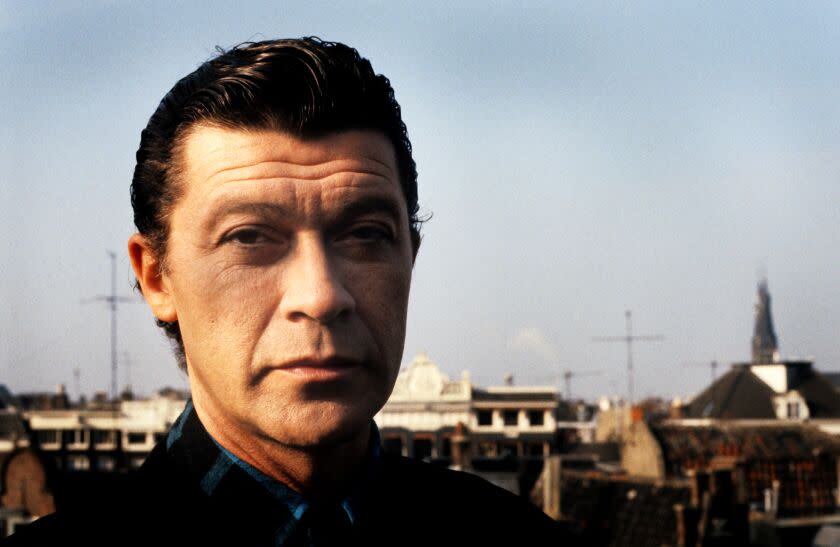

Robbie Robertson, the leader of the pioneering Americana group the Band, entered the pantheon of great rock songwriters early in his career.

By the time the group released its self-titled second album in 1969, it was clear that the Canadian-born singer and guitarist was a masterful storyteller with an exceptional sense of time and space, able to tie together various strands of American music into a sound that felt rooted in tradition yet never beholden to it.

Read more: Robbie Robertson, driving force behind roots-rock icons the Band, dies at 80

The Band was blessed with three exceptional vocalists in Richard Manuel, Rick Danko and Levon Helm (keyboardist Garth Hudson, now the group's only living member, rounded out the quintet). Robertson lacked a graceful voice and rarely sang on Band albums, but as a solo act he figured out how to smartly deploy his low rumble in musical settings that were increasingly adventurous. Such latter-day albums as "Contact from the Underworld of Redboy" are admirable efforts that deserve to be heard in full, but Robertson's legacy resides in his songbook, filled with tunes that have only gained in stature as they recede into history.

Over the course of his career, Robertson, who died on Wednesday at age 80, released seven studio albums with the Band, two live records and five solo LPs. From those, here are 15 of his finest songs:

1. "Yazoo Street Scandal" (1968)

An outtake from the "Music from Big Pink" sessions, "Yazoo Street Scandal" originally surfaced on "The Basement Tapes," the 1975 double-LP that was the first official release of music Bob Dylan and the Band recorded at the Woodstock house they dubbed "Big Pink." Perhaps adding this outtake to "The Basement Tapes" was an act of obfuscation, yet this thick, thundering garage rocker certainly seems like the beginning of something.

2. "The Weight" (1968)

Embraced as a standard almost immediately upon its release, "The Weight" transcended countless cover versions and FM radio spins because ambiguity lurks in its tale of a traveler who finds no comfort in a strange town. There's an undeniable religious undercurrent flowing through the song — the city is named as Nazareth, Carmen is walking side by side with the Devil, Luke is waiting on the Judgment Day — yet "The Weight" finds sustenance in community, a connection that's conveyed through the Band's empathetic harmonies.

3. "Chest Fever" (1968)

If "The Weight" contained traces of ambiguity, "Chest Fever" is where Robertson embraces an enigma. Much of the mystery derives from Hudson, the organist who provides an overwhelming cascade of sound at the song's intro that crests in waves throughout the recording (whenever the Band played it live, it was preceded by an instrumental Hudson showcase called "The Genetic Method"). Robertson's clenched guitar vies for space with Manuel's pained lead vocal, creating a dense tapestry of sound sometimes punctured by a stray lyrical phrase — "she drinks from a bitter cup," "a viper in shock" — that only adds to the song's spell.

4. "Rag Mama Rag" (1969)

Ostensibly a backwoods hoedown, "Rag Mama Rag" is a prime example of Robertson and the Band as American music alchemists. Danko's sawing fiddle suggests that the song is rooted in Appalachian folk, but the number takes some unexpected turns, such as the bass line played on tuba by producer John Simon.

5. "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" (1969)

Written from the perspective of a poor Southerner watching his life and home getting wrecked in the waning days of the Civil War, "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" demonstrates a keen sense of nuance on songwriter Robertson's part. Deftly sidestepping any sympathy for the Confederate, he shows great empathy for the plight of Virgil Kane, his invented Southerner who mourned the losses incurred in the war without celebrating the lost cause. It's a masterful work that carries the weight of the best short fiction.

6. "Up on Cripple Creek" (1969)

Sometimes stereotyped as roots music Puritans, the Band often incorporated modern flair into their rock 'n' roll. Take “Up on Cripple Creek,” an ode to a Lake Charles woman beloved by the song’s roaming narrator. Robertson’s lyrics are teasingly playful but they’re nearly overshadowed by a lithe clavinet part by Hudson that places the song among the funkiest records by a rock band in the late 1960s.

7. "King Harvest (Has Surely Come)" (1969)

A masterful piece of Americana storytelling, “King Harvest (Has Surely Come)” tells the tale of a poor farmer who joined a union after suffering a disastrous season. Robertson doesn’t follow a linear structure — he opens with the farmer starting his allegiance to the union, then works backward to the moment he was compelled to join — and the song has a similarly unconventional musical path. Opening with a nearly hymnal chorus, it rushes through its agitated verses, ending at the point where the narrator is told he has to go on strike, a decision that turns this into a rallying call of sorts.

8. "Strawberry Wine" (1970)

Robertson and Helm concocted a drunkard's love letter to his poison of choice. It’s one of Robertson’s best attempts at writing a roadhouse rocker, a song where the playfulness of the music matched the lyric. It wound up as a showcase for Helm, who gave this a sinewy swing as he milked such evocative turns of phrase as “I could chase a bounty into another county.”

9. "Stage Fright" (1970)

The Band didn’t handle fame particularly well. Several members developed substance abuse problems that made finishing their third album a difficult process. Robertson channeled all this turmoil and nervous energy into “Stage Fright,” a remarkable portrayal of a man compelled to perform despite the anxiety it causes in his soul.

10. "Ophelia" (1976)

A song about a lost lover, "Ophelia" captures Robertson and the Band in particularly high spirits, crossing the elegant New Orleans funk of Allen Toussaint with the deft rhymes of Chuck Berry.

11. "Acadian Driftwood" (1976)

Throughout the Band's heyday, Robertson spun myths and legends about the United States. On "Acadian Driftwood," he turns his attention to his native Canada, writing about the expulsion of the Acadians by the British in Nova Scotia during the 1750s. Robertson's lyric carries the weight of considered history yet his melody is light, adding a bittersweet dimension to one of his loveliest songs.

12. "It Makes No Difference" (1976)

Sung by Danko, who seems wrecked with heartbreak, "It Makes No Difference" ranks among Robertson's saddest songs. There may be abject hopelessness in Robertson's desolate lyrics, but Danko's aching performance and the Band's supple support turn the melancholy into something lovely.

13. "Somewhere Down the Crazy River" (1987)

Robertson may have written the lion's share of the Band's songs but he barely sang on the group's records. When he finally went solo in 1987, ten years after the Band's breakup, he wrapped his voice it in a setting so murky it qualified as noir. That's especially true of "Somewhere Down the Crazy River," where he speaks the verses and lets Sammy BoDean soar on the chorus. It doesn't quite feel like a song so much as a short film filled with shadows and fog.

14. "Broken Arrow" (1987)

Among the songs on his solo debut, "Broken Arrow" had a separate life. Robertson delivered an effective enough performance, but when Rod Stewart covered the song in 1991, he offered a reminder of how other singers could discover depths in Robertson's songs that often eluded the author himself.

15. "I Hear You Paint Houses" (2019)

Since working together on "The Last Waltz," the 1978 documentary of the Band's farewell concert, Robertson and director Martin Scorsese cultivated a lifelong friendship and creative partnership. Robertson scored "Killers of the Flower Moon," the Scorsese film scheduled to be released this fall, repeating a role that he played for many of the director's movies over the years. For "The Irishman," Robertson recruited his old "Last Waltz" friend Van Morrison to duet on "I Hear You Paint Houses," a slow-burning, evocative blues.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.