'2001: A Space Odyssey' turns 50: 5 ways Kubrick classic forever changed sci-fi cinema

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey premiered in theaters nationwide 50 years ago today, and upon that April 3, 1968, bow, it was greeted by both effusive praise and cutting condemnation — a schism epitomized by the dual reviews of the Village Voice’s Andrew Sarris. Initially, Sarris opined,“2001: A Space Odyssey is a thoroughly uninteresting failure and the most damning demonstration yet of Stanley Kubrick’s inability to tell a story coherently and with a consistent point of view.” However, two years later (after catching it again while stoned), he reversed course, stating, “2001 is indeed a major work by a major artist. For what it is — and I am still not exactly enchanted by what it is — 2001 is beautifully modulated and controlled to express its director’s vision of a world to come seen through the sensibility of a world past. Even the dull, expressionless acting seems perfectly attuned to a setting in which human feelings are diffused by inhuman distances.”

Though some critics and audiences didn’t initially know quite know how to process Kubrick’s masterpiece, it soon attained its rightful reputation as one of the medium’s crowning achievements. And in the ensuing decades, no science-fiction film has matched its towering greatness. That’s not to say, however, that many haven’t tried, as Kubrick’s opus naturally inspired generations of futuristic sagas. Between its grand treatment of space exploration, its authentic conception of advanced technology and interstellar travel, and its heady mix of the mundane and the metaphysical, 2001 set a new bar for both science-fiction cinema in particular and big-screen spectaculars in general. To see it now — ideally on a big screen (Warners recruited noted Kubrick acolyte Christopher Nolan to oversee a 70 mm print that is going to be screened theatrically) — is to witness a work that, no matter what today’s calendar says, remains far ahead of its time. In honor of 2001’s legacy as a genre-legitimizing pioneer, we present a rundown of five key ways it helped shape so much science fiction that followed in its wake.

A philosophical soul

To be sure, quality cinematic science fiction existed before 2001. Yet Kubrick’s film (scripted in collaboration with Arthur C. Clarke, who was simultaneously writing a companion novel based on his short story “The Sentinel”) took a headier approach to the genre. Anything but a classical adventure story (or one concerned with straightforward interaction, or conflict, with aliens), it was an operatic cosmic investigation of man’s inherent beastly (and evolutionary) nature — topics that granted it an intellectual weightiness possessed by few of its predecessors. Unsurprisingly, many of its own descendants would take a similar tack, most notably Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris and Stalker, Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, James Cameron’s The Abyss, the Wachowskis’ The Matrix, Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, and Shane Carruth’s Primer, all of which used out-there concepts for more philosophical ruminations about time, space, and consciousness.

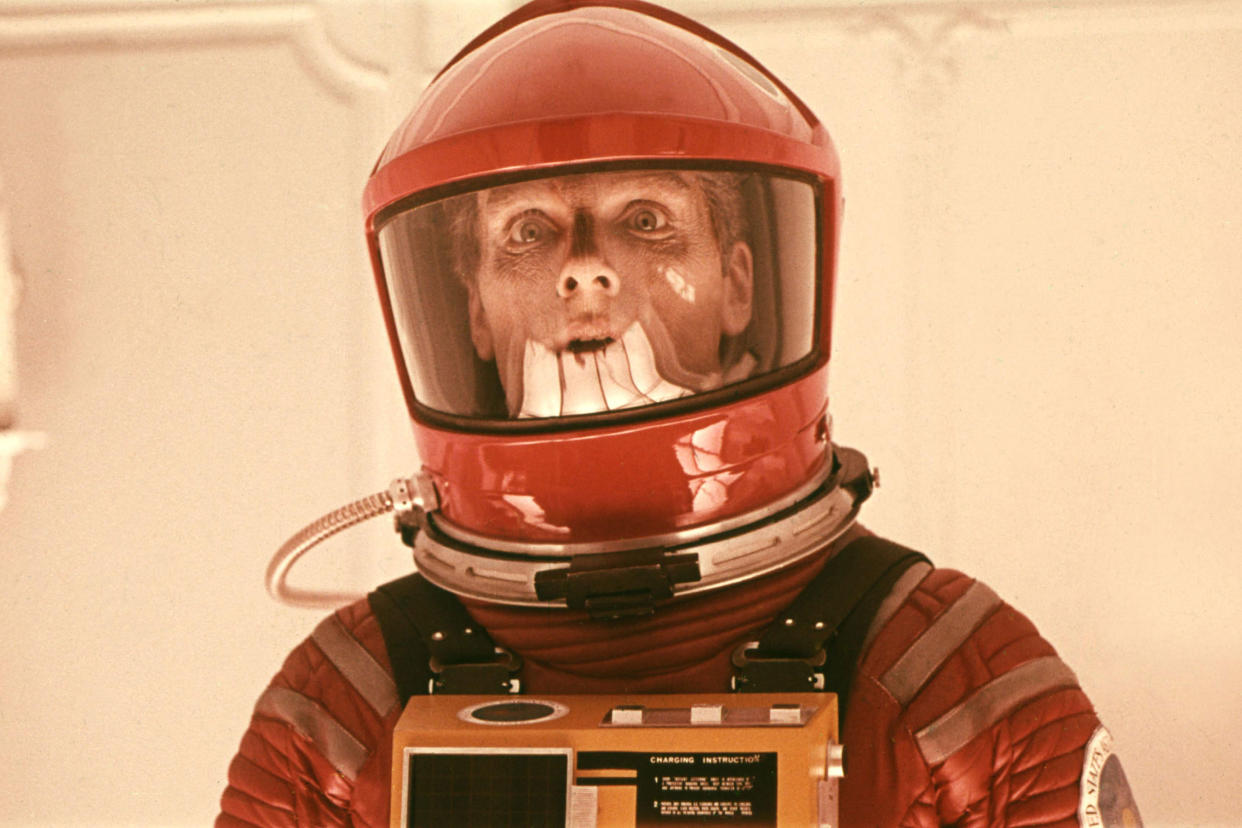

Technophobia

2001 wasn’t the first movie to posit technology as a simultaneous boon to humanity and a potential threat to its continued existence — Fritz Lang’s Metropolis had traversed that territory back in 1927. Nonetheless, Kubrick’s HAL 9000, the calm-speaking artificial-intelligence system that runs the astronauts’ ship, Discovery One, set the standard for villainous sci-fi tech and gave birth to everything that followed, including Westworld’s robot cowboys, The Terminator’s cyborg, The Matrix’s Mr. Smith, and WALL-E’s AUTO — the latter a direct homage to the red-eyed HAL.

Future real

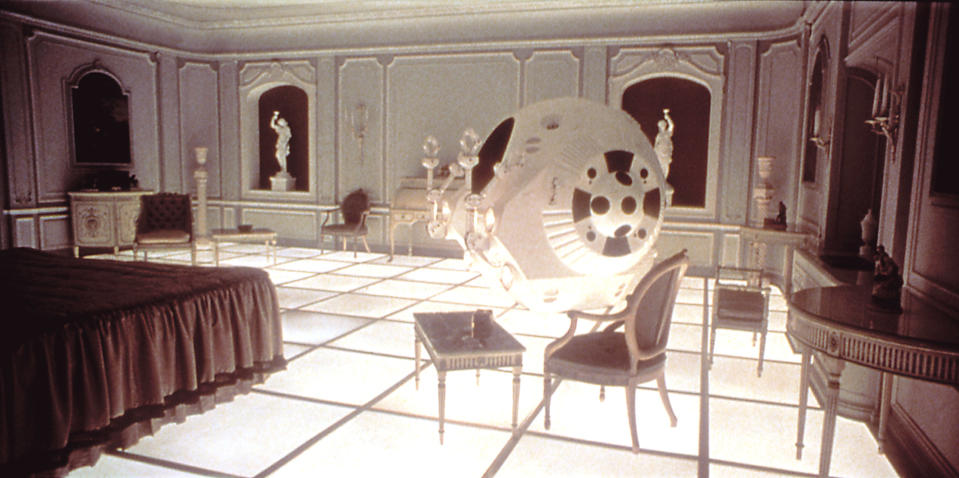

Rather than casting his material as pure fantasy, Kubrick employed numerous experts to help him realistically realize his sci-fi universe. From HAL and the interiors of the Discovery One (including its unforgettable centripetal force set, viewable above) to outer space’s endless silence and stillness, 2001 takes great pains to render its concepts in believable terms. Divorced from the corniness of so much preceding sci-fi, the film’s authenticity was nothing short of bracing, and would become the guiding template for the likes of Robert Wise’s bacteria-fixated The Andromeda Strain, Ridley Scott’s truckers-in-space Alien, Robert Zemeckis’s science-heavy Contact, Steven Spielberg’s future-tech Minority Report, and Alfonso Cuarón’s space-explosion-free Gravity — to name only a few.

Sound and light extravaganza

Kubrick’s attention to scientific accuracy went hand in hand with his meticulous dedication to crafting convincing special effects, such that every moment in 2001 — the towering monolith, the Discovery One, the astronauts’ suits, and the final mind-bending voyage through the cosmos — looks as if it might actually exist in the real world. Its prop, model, and overall production design were second to none. And by raising the bar to such peerless heights, it compelled every sci-fi effort that came afterward to strive for a similar level of effects excellence — including, most notably, 1977’s Star Wars, whose creator, George Lucas, called 2001 “hugely influencing” and “the ultimate science-fiction movie. It is going to be very hard for someone to come along and make a better movie, as far as I’m concerned.”

Furthermore, if 2001’s visuals ignited the imagination of countless filmmakers, so too did its soundtrack of classical and orchestral arrangements — most famously, Johann Strauss II’s “The Blue Danube Waltz” and Richard Strauss’s “Also sprach Zarathustra” — which granted the material a sweeping majesty. Be it John Williams with Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and E.T.; Jerry Goldsmith with Alien and Star Trek: The Motion Picture; or Mica Levi with Under the Skin, ambitious sci-fi has since habitually sought the sort of sonic grandeur found in 2001.

Hallucinatory trippiness

2001’s hallucinatory “Star Gate” sequence (above) became a landmark in psychedelic cinema — and a favorite of counterculture drug users worldwide — for its confounding journey through the farthest reaches of the galaxy. Like nothing that had come before, it paved the way for just about every movie that subsequently tried to bewilder and enlighten through magnificent displays of light and sound. Works such as Ken Russell’s Altered States, Gaspar Noe’s Enter the Void, Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin, Nolan’s Interstellar, David Lynch’s recent Twin Peaks: The Return (see, in particular, Episode 8), and Alex Garland’s Annihilation were all influenced by the far-out artistry of 2001’s signature centerpiece — even if 50 years later, the scene, like the film itself, remains the pinnacle of awe-inspiring sci-fi spectacle.

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment: