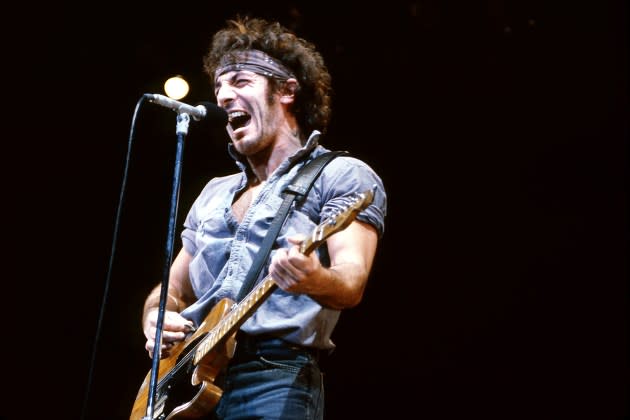

40 Years of ‘Born in the U.S.A.’: The E Street Band Looks Back at Bruce Springsteen’s Biggest Album

Sometime in 1984, when E Street Band drummer Max Weinberg saw a bunch of potential covers for Bruce Springsteen’s next album, he instantly noticed the Annie Leibovitz shot of the singer’s jeans-clad rear end. “My comment, jokingly, was ‘I like that one because that’s the view I always have,'” Weinberg says in the new episode of our Rolling Stone Music Now podcast. “Everybody laughed, and then they picked that shot. And it was a steamroller after that.”

In the new episode, Weinberg and E Street Band keyboardist Roy Bittan take an in-depth look back at the making of Springsteen’s biggest album, Born in the U.S.A. — released June 4, 1984 — and the Brucemania that followed, including the making of the “Dancing of the Dark” video with Courteney Cox. Go here for the podcast provider of your choice, listen on Apple Podcasts or Spotify, or just press play below — a few highlights from the interviews follow.

More from Rolling Stone

See Courteney Cox Reenact Moves From Bruce Springsteen's 'Dancing in the Dark' Video

The E Street Band Wants the World to Hear Bruce Springsteen's 'Electric Nebraska'

See Trailer for New Documentary Focused on E Street Band's Steven Van Zandt

Both Bittan and Weinberg have fond memories of the still-unheard full-band versions of Nebraska songs, in sessions that were entwined with the recording of Born in the U.S.A. “The interesting thing to me about the sort of legend that has grown up around that material is that [the full-band versions] weren’t very good,” says Weinberg. “It’s actually incredibly good! It was just completely wrong for what Bruce wanted to do. And I remember recording all of that material, and it was very much in the E Street Band style, and very similar to what we do now when we play those songs. It was great, and it was a rock record.” (That said, Weinberg makes it clear that there were — obviously — no hard-rocking versions of ballads like “Used Cars,” which were played in a restrained style, a la Bob Dylan’s John Wesley Harding.)

Bittan is proud of the simplicity of the album’s title track. “The song is only two chords,” he says. “Sometimes you can’t be afraid to be primitive, so to speak … To be able to just get down right down into your gut, and just lay into two chords and one riff, it’s elemental rock & roll. Now the fact that I was using a synthesizer is almost irrelevant. I could have been playing that on the piano the same way.”

Steve Van Zandt’s acoustic rhythm parts were more important to the album than they might seem. “I can’t emphasize enough how important Steve was to the rhythmic thrust the songs that eventually came out got,” says Weinberg. “His acoustic guitar, which I was listening to a lot as we were recording, provided a very similar framework as Keith Richards did on, for example, ‘Street Fighting Man.'”

The band was convinced that the best outtakes from the album — songs like “My Love Will Not Let You Down” — were potential smashes. “We used to say, ‘Oh, these are all Number One songs,'” says Bittan. “I think Bruce would write in a direction and then something else would come out and he’d write in that [other] direction. And then eventually he would find the thing that he wanted to say and damn the rest of the songs, whether they were Number One hits or not.”

Weinberg was the first person ever to hear “My Hometown.” “One of the times I was staying at his house,” he recalls, “there were two bedrooms and mine was next to his. Late at night, I remember him writing, and I could hear literally through the door, him writing ‘My Hometown’ on his acoustic guitar. And that I remember distinctly. When he came to record it, he had done it with a Linn drum, just with the beat that ended up on the record. But he wanted me to replace the drum machine. And I overdubbed to what he had pretty much laid down in his house.”

It’s almost impossible to precisely recapture the precise keyboard sounds on the album, due to the quirks of the analog Yamaha CS-80 synthesizer Bittan used (though he switched to a digital synth on “Dancing in the Dark”). “In some ways it was a crude instrument,” Bittan says, “because it had these toggle switches. I think there was four toggle switches, and it opened and closed filters. And that’s how you adjust or change your sound. The funny part about it, it wasn’t a stepped toggle switch. You just moved it, and good luck getting it back to where it was the day before, because there was no way to know. It’s actually a very funny thing that they did. I’ll never understand how they could create an instrument that was so advanced, but yet they couldn’t figure out how to make the dial work.”

Download and subscribe to Rolling Stone‘s weekly podcast, Rolling Stone Music Now, hosted by Brian Hiatt, on Apple Podcasts or Spotify (or wherever you get your podcasts). Check out six years’ worth of episodes in the archive, including in-depth interviews with Mariah Carey, Bruce Springsteen, Questlove, Halsey, Neil Young, Snoop Dogg, Brandi Carlile, Phoebe Bridgers, Rick Ross, Alicia Keys, the National, Ice Cube, Taylor Hawkins, Willow, Keith Richards, Robert Plant, Dua Lipa, Killer Mike, Julian Casablancas, Sheryl Crow, Johnny Marr, Scott Weiland, Liam Gallagher, Alice Cooper, Fleetwood Mac, Elvis Costello, John Legend, Donald Fagen, Charlie Puth, Phil Collins, Justin Townes Earle, Stephen Malkmus, Sebastian Bach, Tom Petty, Eddie Van Halen, Kelly Clarkson, Pete Townshend, Bob Seger, the Zombies, and Gary Clark Jr. And look for dozens of episodes featuring genre-spanning discussions, debates, and explainers with Rolling Stone’s critics and reporters.

Best of Rolling Stone