The 5 best Jean-Luc Godard movies to begin with

The film world lurched today with the news of Jean-Luc Godard's death at 91. Even if the revolution he inspired has faded from public memory (ironically, Godard was once the most fashionably chic of directors), his towering influence will always keep him major. You may not know the movies, but you know the pose: liberated, stylish, defiant, in love with life and its reflection on screen. If you ever wanted to dive into the work of this sometimes thorny but most nourishing of artists, now's the time. Here's a quick beginner's guide detailing the way in.

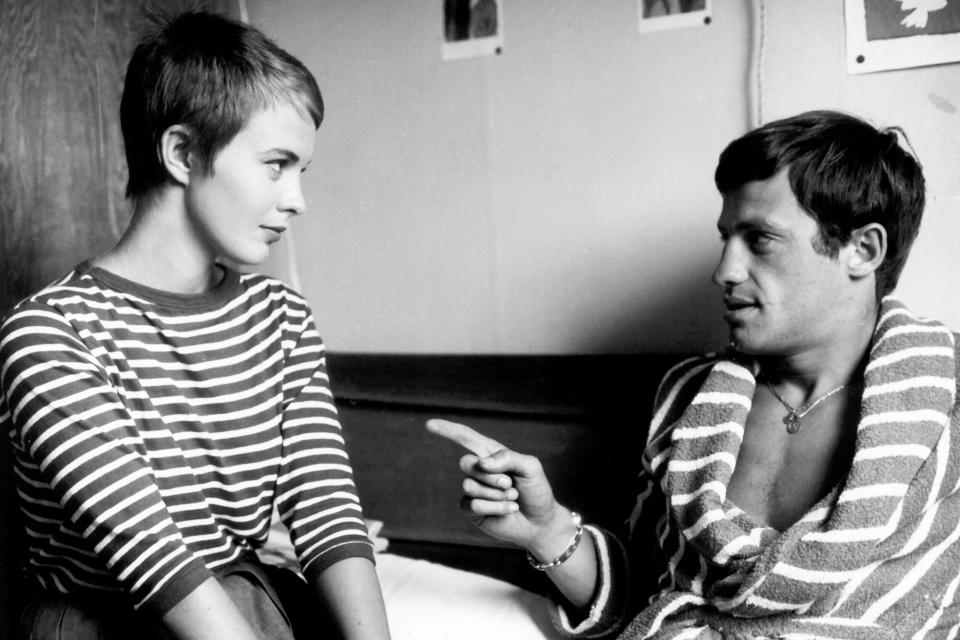

Breathless (1960)

Everett Collection

After a handful of scrappy shorts, Godard got his first feature together, no less rough-and-tumble. But Breathless is the kind of breakthrough that thrives on energy, not polish. Here — for the first time, really — was a film that shuddered with movie obsession. Jean-Paul Belmondo's Bogart-loving half-gangster and Jean Seberg's pixie-cut American in Paris are creations both for the screen and of the screen. Godard's intentional use of skipping jump cuts drew attention to the watching of films, at a moment when such glitches were considered mistakes. If you thrill to Tarantino and the idea of cinema in gabby conversation with itself, here's where that whole thing started.

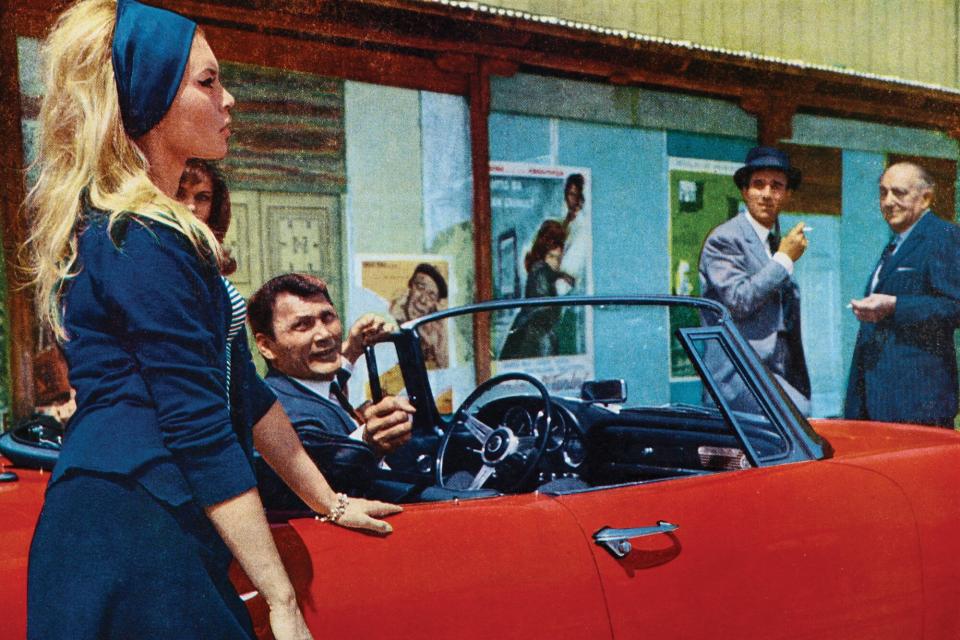

Contempt (1963)

Everett Collection

Godard's technique got better in a hurry, and this romantic tragedy remains his most perfect concoction of self-awareness and pure entertainment. You still get the sudden shifts of color and in-jokes (M's Fritz Lang appears as himself), but essentially, it's a story about a screenwriter (Michel Piccoli, a clear stand-in for Godard) whose tunnel vision blinds him to the fact that his wife (Brigitte Bardot) is drifting away from him. Graced by an aching orchestral score by Georges Delerue that drenches everything in fatalistic gloom, Contempt is the one that will turn you into a convert.

Pierrot le Fou (1965)

Criterion

If you somehow added those first two titles together, you'd get this one, enlivened by impulsive faux-criminality but also struck by a truly gorgeous use of color and style. Belmondo is back, shaggy and likable, but also there's Godard's wife and muse Anna Karina, whose explosive energy made her the iconic Charlie Chaplin of the French New Wave. Much of the movie takes place on the run, which could be interpreted as Godard himself suggesting that he was always rushing toward something, hoping to never get rooted in sameness. For the moment, he is free.

Masculin Féminin (1966)

Everett Collection

Like the Beatles' playful apotheosis Revolver (released the same year), Godard's Masculin Féminin feels like the beginning of a new era: a drifting, electrifying ode to pop lifestyles. Madeline (Chantal Goya) hopes to make a yé-yé record. Her dream comes true; there's also a gun, some political protesting, sex, and several to-the-camera interviews, a device that felt extremely fresh at the time, especially for fictional characters. In an intertitle, Godard calls them the "children of Marx and Coca-Cola." A former critic, he turned his films into cultural statements.

Goodbye to Language (2014)

Everett Collection

Common wisdom (not wrong in this case) has it that Godard settled down after his first decade of explosive work, if not fully relaxing then drilling down into his political preoccupations at the expense of fun. But it would be a shame to write off his subsequent decades of heavy experimentation. Take a taste with this 3D movie — yes, even Godard made one — that blurs boundaries, and includes plenty of visual tricks that have yet to be fully explored. Let its ideas flow over you; grab the ones you like. Godard wanted us to enter movies as co-creators. That's a notion we should never forget.

Related content: