What is Afrofuturism and why should you be reading it? We explain.

It has been called a movement, a genre, a cultural aesthetic.

Afrofuturism is all of those, but it's also more than a promise that Black people exist in the future. It's more complex than taking Afro-centric concepts and infusing them with technology or futuristic imaginations.

Its literary roots run deep, and books that might now be labeled as Afrofuturism have been around for decades. From the 1920 short story "The Comet" by W.E.B. Du Bois to the short stories and novels by Samuel Delany published as early as 1960, the genre has long been evolving.

The movement is so wide-reaching that it has extended beyond literature to music, movies, art, television and fashion.

Octavia E. Butler, author of award-winning novels such as "Parable of the Sower" and "Kindred," is often called the mother Afrofuturism. The term "Afrofuturism" may not have been as widely used when Butler was writing, but her work certainly has influenced the movement and decades of film, television, books, art and music.

Amanda Gorman: Debut poetry collection 'Call Us What We Carry' inspires fellow WriteGirls

Key themes in her writing are race, feminism, class and reclaiming identity, often wrapped in historical or apocalyptical settings. Butler, who died in 2006, was the first science fiction writer to receive a MacArthur "Genius" Grant and won Hugo and Nebula awards, the top science fiction and fantasy awards. But her books also seemed to be bigger than just one literary genre.

If Afrofuturism is an aesthetic, what are its underlying characteristics?

What is Afrofuturism?

Author and culture critic Mark Dery is credited with coining the term "Afrofuturism" in his 1993 essay, "Black to the Future," which was published in a 1994 anthology, "Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture."

"Speculative fiction that treats African-American themes and addresses African-American concerns in the context of twentieth-century techno culture – and more generally, African-American signification that appropriates images of technology, and a prosthetically enhanced future – might, for want of a better term, be called 'Afrofuturism,'" Dery writes in the essay.

The definition of Afrofuturism that author and educator Tananarive Due uses is "the speculative arts of the African diaspora."

Due, who teaches Afrofuturism at UCLA and also has an online course, acknowledges that this definition is very broad and that it includes "science fiction, which is what most people think of because of the word futurism, but also fantasy, horror – which is a form of fantasy – magical realism, comics – the list goes on."

When it comes to Afrofuturism, there are "degrees," says illustrator and Afrofuturist Tim Fielder.

"Some Afrofuturism I think is much more directly Afrofuturist, and then there are those that lean toward the science fiction element and just the presence of people of color are enough to make it Afrofuturism," Fielder says.

When he wrote and illustrated his graphic novel "INFINITUM: An Afrofuturist Tale" (Amistad, 288 pp.), about a king who is "gifted" with immortality and faces many events in history, Fielder said he used the trope of immortality to bring in more fantasy and contemporary elements "to cover the entire spectrum" of Afrofuturism.

And the boundaries of Afrofuturism may be changing.

Culture journalist, host and author Karama Horne, also known as "theblerdgurl," points to how generational differences might be influencing changes within the movement: Gen-X and older often lean toward a more rigid definition, while millennials and younger fans tend to mix the labels.

"I remember having conversations years ago about Afrofuturism and what it meant – the meaning, the philosophy," Horne says. "And then I feel like the internet came and it exploded and now, internationally, everybody has different definitions of it. It's morphed and become – with time and this digital injection – something else."

Afrofuturism can feel like a "vibe," says author Tochi Onyebuchi, but it aims at "using the intersection of African diasporic culture and melding it with science and technological imaginations in an effort to repair the primordial wounding caused by chattel slavery."

Author Walter Mosley wrote a column in The New York Times in 1998 exploring why science fiction may be appealing to Black people, how it allows history to be rewritten and the promise it holds – "a literary genre made to rail against the status quo." But Mosley, in praising more mainstream writers like Butler and Delany, wondered "where are the Black science fiction writers?"

Mosley predicted a literary movement would be coming, and there would be an explosion of science fiction from the Black community.

In the midst of an Afrofuturism renaissance

When Marvel's film "Black Panther" – set in futuristic fictional African country Wakanda, its themes blending African diaspora, superheroes and social issues in the Black community – was released in 2018, it sparked new interest in Afrofuturist art.

Due also credits "Get Out" (2017), and Horne credits The CW's "Black Lightning" (2018) and the animated film "Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse" (2018) for adding to the heightened interest.

Alongside the movies and show, the reemergence of Butler's prescient works during the coronavirus pandemic and the rise of award-winning author N. K. Jemisin added to the literary movement.

"We're in the midst of a renaissance right now," Due says. "Writers are arising in public consciousness because they're doing such excellent work that speaks to so many readers."

And young writers have continued to be inspired.

"Some writers like me and Octavia Butler and my husband, Steven Barnes, we've had experiences where white characters were put on the covers of our books because editors didn't think they would sell," Due says. "Now we're in a world where there are beautiful Black faces on these book covers, especially in young adult fiction."

Says Onyebuchi: "In Afrofuturism, I think there can be this sense of hope and possibility in centering Black Americans in the story and the story world, even if the tale itself is dystopian or the world in which the tale is set is dystopian. "That's very powerful, the centering of Black people."

"And Afrofuturism as a vibe – that concept is new, and I think that's come out of the 'mainstream-ification' of just about everything Black," Horne says.

"Labels, genre labels, subgenre labels more generally are aids for readers than they are for writers," Onyebuchi says. If they help readers find new works and new writers to enjoy, all the better.

Black to the Future

The future will be here before we know it.

"One of the things that I wanted to do with 'Riot Baby' was show some of the ways in which the future can kind of creep up on you," Onyebuchi says. His 2020 science-fiction novella (Tor, 176 pp.), which starts during the Los Angeles riots, follows two siblings as they develop superpowers and deal with generational pain. It was nominated for several awards, including the Nebula and Hugo awards.

What's next for Afrofuturism, and how might the genre change?

"So philosophically, I think it's literally important to open up society's imagination to worlds of possibility that are coming outside of the same creators we have celebrated in the past," Due says. "There's great work in science fiction and fantasy by all kinds of writers. But the joy of embracing Afrofuturism is a new vision and new voices. That's just good for everyone."

"It'll be interesting seeing all the different ways in which Afrofuturism as aesthetic makes itself more expansive in literature," Onyebuchi says.

"I would like to see even more empowerment and inroads in cinema and television, especially television, and of course, more, even more parity in publishing," Due says.

"I just think it's going to take us to claim it, reclaim it for it to really take root and be able to move into the future," says Horne, whose book on the Dora Milaje of "Black Panther" fame is set to publish in September 2022. "Just like we're seeing across between the music and gaming, we're going to see more intersectionality between genres. I mean, how amazing would the Janelle Monáe cinematic universe be?"

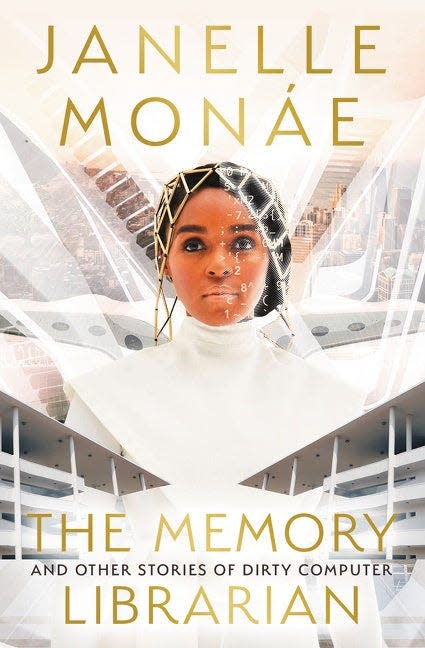

Monáe, the actress, singer, fashion icon and self-described "android" known for roles in the films "Hidden Figures" and "Antebellum" and her neo-soul/pop rock sound on her albums, including 2018's "Dirty Computer," made her literary debut in 2022 with "The Memory Librarian: And Other Stories of Dirty Computer" (HarperCollins, 316 pp.). The short story collection is a collaboration with nonbinary and female writers of color set in the dystopian world from "Dirty Computer" and accompanying short film.

Onyebuchi looks forward to seeing how intentionally expansive Afrofuturism becomes.

"I think at the moment there's an Afrofuturism that intersects themes and concerns of the African diaspora with technoculture and speculative fiction, but a lot of it can throw itself at examination of social issues in a very particular way," Onyebuchi says. "It'll be interesting seeing a strand of Afrofuturism that doesn't do that, or that strays away from that, or doesn't necessarily seem to be that immediate impulse towards social critique."

"Afrofuturism is not just about works related to showing the future," says Due. "It also tends to hold the past, present and future in the same space."

As we look to the future, the truth is, it may already be here.

Afrofuturism: A beginner's reading list

"The Memory Librarian: And Other Stories of Dirty Computer," by Janelle Monáe and other authors (2022)

"Kindred," by Octavia E. Butler (1979)

"Parable of the Sower," by Octavia E. Butler (1993)

"Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora," edited by Sheree Renée Thomas (2000)

"Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture," by Ytasha L. Womack (2013)

"The Fifth Season," by N. K. Jemisin (2015)

"How Long 'til Black Future Month?" by N.K. Jemisin (2018)

"The Between," by Tananarive Due (1995)

"War Girls," by Tochi Onyebuchi (2019)

"The Deep," by Rivers Solomon (2019)

"Elysium," by Jennifer Marie Brissett (2014)

"The Blood Trials" by N.E. Davenport (2022)

"Children of Blood and Bone," by Tomi Adeyemi (2018)

"Binti," by Nnedi Okorafor (2015)

"Zone One," by Colson Whitehead (2011)

"INFINITUM: An Afrofuturist Tale," by Tim Fielder (2021)

"Tales of Wakanda," edited by Jesse J. Holland (2021)

"Devil's Wake," by Steven Barnes and Tananarive Due (2012)

"Nova," by Samuel R. Delany (1968)

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Afrofuturism: Black writers explain the important literary genre