Alan Parsons is a punk with no regrets – well, not many

In 2014, the release of The Complete Albums Collection box set offered Alan Parsons the opportunity to reflect on the highs and lows of the Alan Parsons Project – including the defiant act of recording a contractual obligation album in three days.

It takes a certain aptitude and self-assurance to turn down Pink Floyd – yet after masterfully engineering The Dark Side Of The Moon in 1974, Alan Parsons declined an offer that most of his contemporaries would have gleefully accepted.

“It was a difficult decision and they made me a very good offer to work with them full time, not just to work on Wish You Were Here,” he reveals. “They asked me to do all their live and recorded sound but, by the time that offer came, I was already having success as a producer with the likes of Pilot and Cockney Rebel. So I decided to pass and continue on my path, as I felt I was doing something right at the time.”

For all the plaudits and everlasting recognition Parsons has received for one of the Floyd’s pivotal recordings, there have been a few niggles that have surfaced over the intervening years – not least David Gilmour’s one-time assertion that they “would have got there with any engineer operating the knobs and buttons.”

“Yes, occasionally it was upsetting that David Gilmour would say that the album would have been just the same no matter who’d engineered it,” says Parsons with a tinge of sadness. “He later retracted that remark and both Roger and Nick have always been very complimentary. Of course the biggest blow of all was when I wasn’t asked to do the surround sound version. That was unforgivable.”

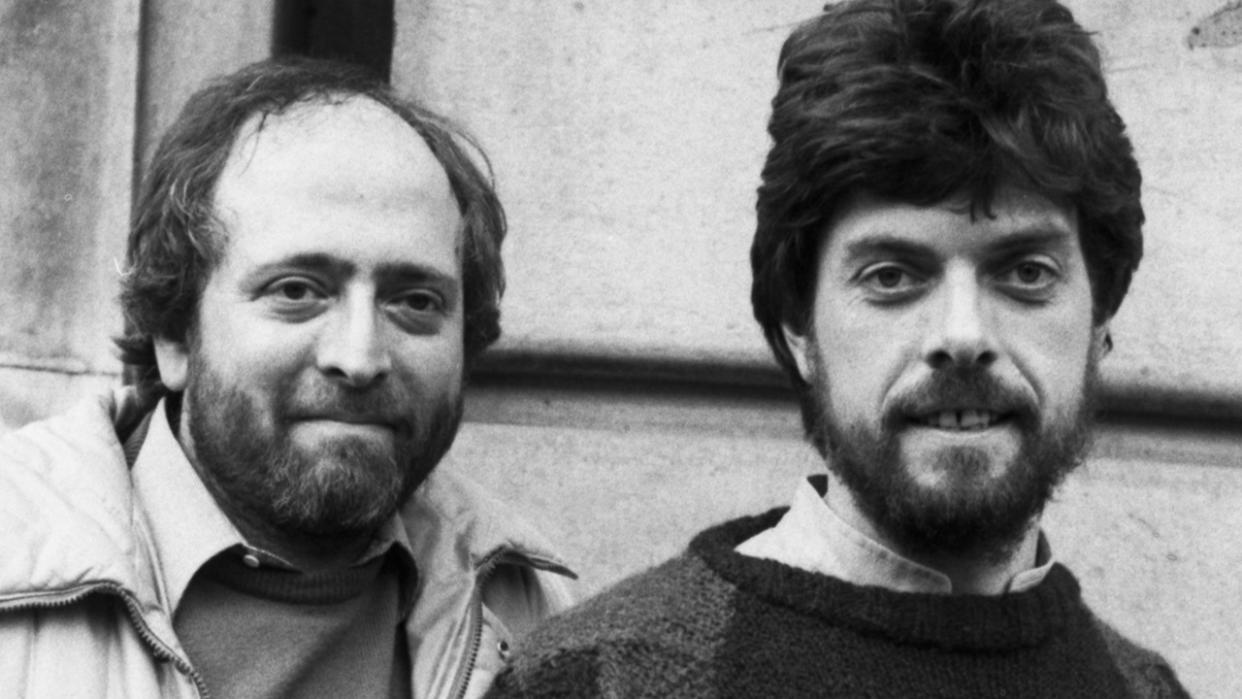

Venturing away from Floyd at least gave Parsons the opportunity to form his intensely successful partnership with Eric Woolfson in the Alan Parsons Project. Adopting a revolving-door approach to using other musicians and vocalists – in excess of 30 musicians appeared on their albums – they created ten hugely successful records between 1976 and 1987.

The recent release of The Complete Albums Collection box set collating these recordings has given Parsons the opportunity to critically review the material. So has time provided him with a positive perspective and a renewed sense of pride?

“There was that feeling on occasion; but there was also the feeling of, ‘Why did we do that?’” he laughs. “But yes, it was nice to be able to listen to them all the way through again, as I really hadn’t done that in a long time.

”I have certain favourite songs such as Limelight, and Stereotomy was a good album, but I still maintain that the first album, Tales Of Mystery And Imagination (Edgar Allan Poe) is the one. It was the time when I could get the most ideas off my chest. That remains the one that I’m most proud of.”

The set also includes their mysterious Sicilian Defence album, which until now had remained in the vaults of the record label. This “contractual obligation” album was recorded in three days as the ultimate statement of petulance at the label’s insistence that they provide another album.

I was surprised when we were called progressive rock; I think progressive pop would have been better. There is very little in the way of the lengthy solos and only occasional odd time signatures

Yet for all the anticipation, Parson’s reveals that the legend of this missing album may not quite live up to the hype generated over the last two decades. “People may think that it wasn’t justifiably long awaited,” he laughs, self-deprecatingly.

“It’s a piece of history. It was a contractual obligation album and wasn’t meant to be a serious release. I mean, it’s not totally crap, and it’s a collection of instrumental demos that may one day have seen the light as proper songs. So they’re pretty unpolished, shall we say.

”It’s okay and not as bad as I thought it was going to be when I first heard it again after 30 years. I really didn’t think it would emerge again, but it was something that would crop up in interviews.”

Eric Woolfson died in 2009. His daughter Sally says: “It’s a very interesting bonus album. Dad listened to it before he died and it rather amused him remembering back to the circumstances in which they made it. They were at odds with the record label and said, ‘Well, you want an album, we’ll give you an album,’ and then doing it in three days. It was a little tongue in cheek in places; I think he would be very amused and pleased that it has ended up in this box set.”

With the band avoiding live performances until the 1990s, The Alan Parsons Project were a pretty faceless act, relying on album success to drive their immense popularity. Indeed, with hindsight, it’s a remarkable feat that an act with such a low public profile and the moniker of their producer managed to amass such a huge level of support. When you consider they came to prominence at the height of punk, their achievement is even more inspiring. So how does Parsons explain that success?

“I think we were punk rebellion,” he says, without any hint of irony. “Concept albums had been proved to be de rigueur at the time. We really struck gold by releasing I Robot at the same time as Star Wars, which helped. There was just a corner of the market that we fitted into on progressive rock radio. Pink Floyd, Genesis and Yes were getting lots of play on certain radio stations and back then radio really sold records.”

Timing aside, they were also able to tap into contemporary music of the time, whether that was with the aforementioned sci-fi tones of I Robot or the new wave influences that infiltrated Pyramid. They had the grand concepts which fitted the progressive mould – but pop was as much as part of their sound. It’s not lost on Parsons.

“I was kind of surprised when we were called progressive rock as I think progressive pop would have been better,” he considers. “There is very little in the way of the lengthy solos which prog rock became famous for and only occasionally were there odd time signatures. Songs like The Games People Play and Eye In The Sky were pure pop. What made it progressive was the epic sound and the orchestration which very few people were doing that at the time.”

Sally Woolfson adds: “My dad always tried not to be pigeonholed. The Alan Parsons Project was an interesting idea in itself, where you could hand-pick the musicians and you were marketing it based on the producer and engineer. They had the freedom to pick lead singers depending on the material and weren’t trying to mould it for the artist. Many of the musicians really enjoyed it, as there wasn’t the pressure of it being their solo album. They could just come in, do their thing, and go off and do whatever else they were doing.”

If we toured we could have become as big as anybody, and been a stadium act. We just felt that the orchestral sounds could not be faithfully produced enough

There is, however, a palpable sense of regret that the band delayed touring for the best part of 20 years. Parsons does now embark on lengthy Alan Parsons Live Project tours, but there had previously been a reticence to perform live that seems to have been rooted in a belief that the records could not be faithfully reproduced.

“We should have done it and gone out there, as even with a small orchestra it would have been fine,” he sighs. “I deeply regret not doing that. If we toured we could have become as big as anybody, and been a stadium act. We just felt that the orchestral sounds could not be faithfully produced enough; by the time we did start playing live, synthesizer technology was such that you could record and reproduce sounds. That was the first time it had happened.”

Sally Woolfson also points out that, by having a producer as the band leader, who at that time rarely played on albums or live, would have been a hindrance. “Alan would perform only small amounts on the odd track – his role was really behind the mixing desk. So how could you tour something called The Alan Parsons Project? The idea that you would have musicians on stage and a spotlight on Alan at a sound desk, in the back of the theatre, didn’t really work.

“The other aspect was that dad didn’t crave the limelight and was very nervous of fame. So there was a level of protection that came as a result of not playing live. He could enjoy the success without the fame. He saw what fame did to other people in the industry and their children and the invasion of privacy. He was a very private man and didn’t want to give that up.”

Parsons is set to continue touring in South America and Europe during this year, once again eschewing any UK dates. So when can British fans expect to see him? “To be honest, I’m waiting for the phone to ring and we haven’t found the right promoter in the UK yet,” he explains. “But I’d love to do it…”