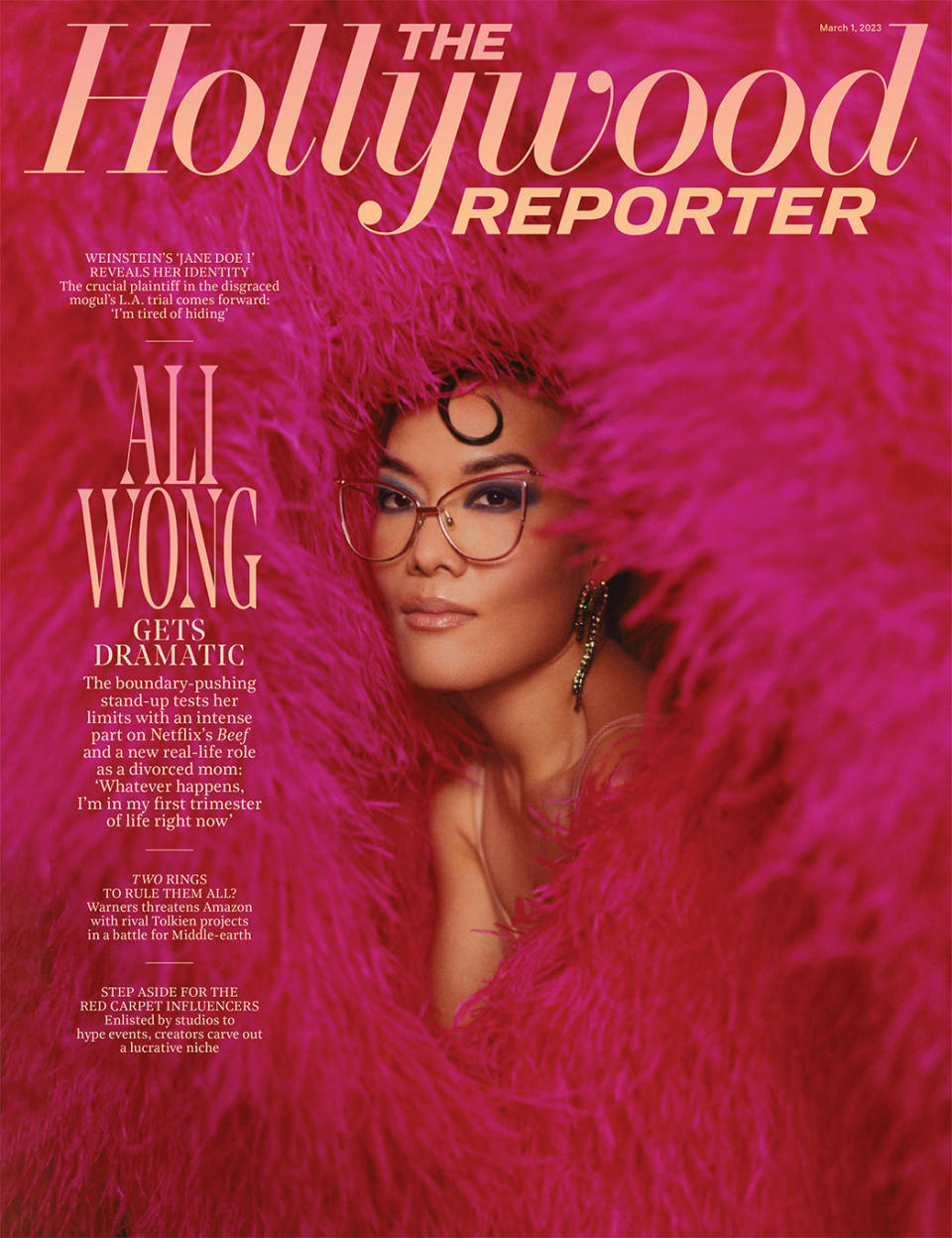

Ali Wong Gets Dramatic

“Do you have a breast pump?”

This is how Ali Wong greets my visibly third-trimester self when we meet up at Etta in Culver City for lunch in February. By the time we make it to our table, she is already whipping out her phone to text her assistant to deliver a pump to my apartment, and she spends the first 15 minutes of her interview focused on my pregnancy: how many weeks I’m along, how I felt during my glucose test (she’s the only person who’s ever asked me about that often-nauseating experience) and her three must-brings to the hospital for delivery (a breastfeeding pillow, a nice blanket from home and a pack of Depends).

More from The Hollywood Reporter

'Beef' Creator Lee Sung Jin on his Original Ending, "Life-Affirming" Feedback and Season 2 Plan

Annette Bening on Meeting a "Dire" Moment, From Hollywood Strikes to Attacks on LBGTQ Rights

“I really miss being pregnant,” sighs Wong, 40, who famously was with child for each of her first two stand-up specials, 2016’s Baby Cobra and 2018’s Hard Knock Wife. “Sometimes it feels a little lonely to be onstage without them,” she says.

Her career, too, is growing up. On April 6, Netflix will premiere A24’s dark comedy series Beef, in which she stars opposite Oscar nominee Steven Yeun as Amy, a high-achieving working wife and mother whose road-rage encounter pushes her into increasingly destructive territory. Her first dramatic lead, it’s a career milestone, and a personal one.

“For me — and I’ll leave it up for interpretation what this means — it was a way to say what I’ve been wanting to say about relationships and being a working mom that I haven’t found a way to talk about onstage,” Wong says.

She recently watched the first two episodes with her ex-husband, Justin Hakuta — the two announced their divorce in April 2022, while she was filming Beef. ” ‘Ali, it’s really good,’ ” she recalls him saying. ” ‘And I also feel like our lives might change again.’ “

***

The last time Wong’s life changed dramatically was seven years ago (“Not that long,” she muses), when Netflix released Baby Cobra. Although the streamer remains frustratingly tight-lipped about viewership metrics, there’s no shortage of evidence of how Wong’s profile shot up after the special landed on the platform on Mother’s Day 2016. The raunchy, revelatory hour launched her from offering discount shows on Groupon in her hometown of San Francisco to selling out an eight-date stand at the SF Masonic Auditorium a year later, to regularly sold-out residencies in cities from New York to Chicago to Los Angeles. Her very pregnant performance ensemble was memefied as a Halloween costume and immortalized by the Smithsonian, which has her $8 striped H&M dress on display at the National Museum of American History.

Sex, motherhood and the gender double standards faced by successful women are recurrent themes in Wong’s work, from her comedy specials (she followed up Baby Cobra two years later with Hard Knock Wife and then 2022’s Don Wong) to her 2019 New York Times best-selling comedic memoir Dear Girls to her semi-autobiographical characters in the Netflix rom-com Always Be My Maybe and now Beef. “I think that everything that I am talking about, even though it’s not specifically about my kids, is still rooted in motherhood,” says Wong, whose daughters are now 5 and 7. “And like being a woman and being Asian American, it’s something that is always inherent and that I never feel the need to speak to overtly but also am never scared to hide from.”

Despite, or perhaps given, her meteoric rise to the comedy A-list, Wong felt humbled by the challenge of her new project, whose deceptively simple and potentially silly logline (“Two strangers take a road-rage incident too far”) belies an escalating existential undoing.

“I’m guessing that Steven could probably sense that I was a little intimidated and nervous about co-leading with him, because at this point he’s like an icon,” she says. “Before filming he looked me in the eye and said, ‘I don’t know anything you don’t know.’ And either he’s a really good actor or he meant it, because it really leveled the playing field. If he hadn’t said that to me, I don’t know if I would have been able to perform the way I did.”

The two didn’t know each other well before this project — despite voicing literal lovebirds on Netflix’s animated Tuca & Bertie, on which Beef creator Lee Sung Jin was a co-executive producer — but Yeun was a fan. “I was still working on Walking Dead, and I had just seen [Baby Cobra] on my laptop in my trailer,” he says. “And I rarely ever do this, but I DM’d her on Twitter and was like, ‘You’re so awesome. Thanks for putting this out.’ ” (In a 2016 Reddit AMA interview to promote the special, Wong cited his as the most meaningful celebrity endorsement: “I JUST ABOUT DIED,” she wrote.)

“We always knew that [Beef] was going to be asking to dig into sides of ourselves that maybe we don’t normally dig into,” says Yeun, who plays Danny, a down-on-his-luck contractor on the other side of the titular feud. “And so it was really cool to see her go there and be willing to be so courageous and just hang in that pocket.”

Lee originally envisioned his two protagonists as more literal stand-ins for the real-life motorist conflict he experienced with a middle-aged white man. “Our heads went to a Stanley Tucci type,” he said of a very early pitch he was mulling with Yeun, when Wong called to chat about an unrelated matter. “It gave us an opportunity to catch up, and she’s so funny in the way she describes tougher things. She can be describing something that is emotionally painful and it’s just cracking me up. So in that moment on the call I was like, ‘Man, this is interesting.’ “

Lee pitched the reimagined role to Yeun and A24 and then Wong, who agreed to come on board. Beef quickly became a hot package in March 2021, with Netflix prevailing in the weeklong bidding war that ensued.

For Lee, there was never a doubt that Wong could pull off the complicated character of Amy, whose enviably perfect exterior masks a void of self-loathing and despair. “I know she hadn’t shown this range before, but I could just feel in her work and onstage that she has a great command over her voice and body and how to elicit a reaction from an audience. She’s so precise,” says the first-time showrunner, whose TV writing credits include It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia and Silicon Valley. “It almost felt like it was a leap of faith on her part to trust me, because nothing I’d written so far would indicate I can actually do this. So I’m pitching her all these wild things, and if I was unsure of a scene, she would push me to go further.”

Wong’s finely tuned sense of observation helped shape the development of her character’s mother-in-law (“She told me a lot of stories that were basically a composite of some of her exes’ mothers,” Lee says), and she even pitched what became the closing shot of the entire series. And one revealing scene in the pilot that establishes Amy’s interior life came out of a brainstorming session between the two friends: “Amy’s this repressed character. I wanted her to have her private thing that she could funnel [her emotions] into,” Lee recalls. “We were talking about how much we love The Sopranos, and there’s that very funny scene where Richie Aprile and Janice are having sex and he’s pointing a gun at her head. And so we fully dove down and landed on gun masturbation.”

Wong notched a lot of new experiences making Beef -— tearing through forests in the dead of night, shooting her first sex scenes on camera — but none was more daunting than a decidedly nonphysical scene when Amy goes to therapy to discuss her crumbling marriage, her insecurities about motherhood and her fears about conditional love. “It’s a nervous scene to shoot, an extreme close-up, and the camera’s moving at the same time. We were curious how it was going to go, and she went there take two,” Lee recalls. “You could see the emotion bubbling up in her eyes and the tears forming, and it’s no surprise that the hives came out because there was no separation between her and the character when she was in it.”

Says Wong of the scene, “It was a long speech I gave that [Lee] wrote. He didn’t say, ‘You have to cry.’ I just ended up crying. Now when I watch it, I can’t believe that happened. Like, who is that person? I really don’t recognize that person.”

Wong and Yeun both broke out into hives after filming ended around May of last year. “I think I saw it throughout the whole shoot — this was taking a toll on them physically because these characters, there’s a lot going on. The pain is heavy,” says Lee. “Once we wrapped, we all cried, but Ali cried for a long time. I think she was holding a lot of the pain of that character in, and it all came pouring out.”

***

Wong’s fearlessness in her stand-up toward speaking out loud the unspoken resentments and impolite desires of the modern multitasking woman has led many viewers to feel like intimate witnesses to her personal life, especially her marriage, which was often explicitly mined for material. It is perhaps why the April 2022 announcement of her divorce from Hakuta, a tech executive who became her tour manager, landed with more impact than the typical celebrity-civilian split.

“I did not expect the announcement to be so widespread, but by far the hardest part about getting divorced was my mother’s reaction,” she says. “I had told her before that I thought we might get divorced, and she was really upset. She looked me in the eye and asked, ‘Can you just wait until I die?’ She was literally asking me to not live a life for myself. But she’s 82, what do I expect? She hasn’t had her period in 40 years. She’s in the sha-ha-hallows of senior citizenship. But it was still really fucking hard dealing with all her fear of the shame it would bring her.

“But then, what was kind of cool about the announcement was that she didn’t have to tell any of her friends. All of them found out because it made it to a bunch of the Chinese and Vietnamese newspapers — I still can’t believe why on earth they would be interested in me — and they all called her. She died a million deaths in one day and then woke up the next day and was like, ‘I survived.’ She still sees Justin a ton.”

Wong’s most recent special, Don Wong, premiered just two months before news of the split and has thus been dissected for its many riffs in which the comic fantasizes about cheating on her husband and returning to the single life (even though the set ended, in a typical Wongian full-circle twist, with an affirmation of all the attributes she appreciates about him). Her Beef character, incidentally, is also married to a hot, doting Japanese man and cracking under the pressures of being the household breadwinner. But when asked whether she’s concerned about how people might read into her work and make assumptions about her personal life, she answers right away: “I can’t help that. Not really.”

“All of those things that she brings to the stage, they’re a part of her and inside of her, but on a real-life level, she’s very grounded and I think protective of the things that matter most to her, which are her family and her friend group,” says Randall Park, who has known Wong since she was an undergraduate at UCLA and starred opposite her in Always Be My Maybe, which they co-wrote with Michael Golamco. “She’s able to separate her life from her art.”

Says Wong, “I don’t put the pressure of ‘this is the whole me’ [on my work]. All of this — my stand-up, Beef, Always Be My Maybe, how I am with my friends, how they relay a conversation I had with them — is never going to be the whole truth. It is always going to be an abstraction of truth, and I think that’s very comforting. I can’t help what people expect. I don’t try to control what they think or take away at all. That’s not the goal. The goal is to surprise them and make them laugh and make myself laugh and have fun.”

At least part of Wong’s truth — which indeed can be gleaned from her stand-up monologues, which have laced ironic affection for her family amid the profanely comedic laments — is that she and Hakuta are not just co-parents but still friends.

“We’re really, really close; we’re best friends. We’ve been through so much together. It’s a very unconventional divorce,” says Wong, who played pickleball with her ex-husband on this very morning and will travel with him and their daughters when she goes back on tour in June with new material about her post-divorce dating life (she was briefly linked to Bill Hader late last year). “I’m still workshopping it, but the bones are there and it came to me very fast. This is the first hour I’m doing since I started where I’m single. I think we’re going to call it the Single Lady tour.”

***

“I probably should think about it more, but it’s so hard to come up with a funny joke that I don’t edit [myself] and think about things as much as you think I do or should,” Wong says of her approach to writing, which she notes hasn’t changed despite the dramatic transformations in her life — and the increased attention that has come with them. “I’m very blessed, I think, because of how I grew up. Other Asian American people in entertainment have spoken to this when they’re like, ‘You just seem very free.’ I haven’t known any other way. I have my [family] and the communities that I grew up in to thank for that.”

Her maternal grandfather sent her mother from Vietnam in 1960 to study in the United States, where she met Wong’s father, a first-generation Chinese American anesthesiologist. Wong credits her parents for immersing her and her three older siblings in the Asian American community as well as for nurturing their creative expression from a young age. She majored in Asian American Studies at UCLA — which she often refers to by its insider nickname “University of Caucasians Lost among Asians” — and joined Lapu, the Coyote That Cares, co-founded by Park and now the largest Asian American college theater company in the nation. Amid her inner circle are seven college girlfriends with whom she remains very close. “With the exception of one, we all live in Los Angeles within five to 10 minutes of each other. We had kids at the same time,” says Wong. “They’re lawyers, graphic designers, doctors, pharmacists, and I’m the third-funniest woman in that group. And yes, they’re all Asian American.”

Although Wong wrote “big shot lawyer” (in addition to “have a million babies”) under “Career Aspirations” in her LCC bio, after graduation she moved back to San Francisco to embark on life as a stand-up. “She was basically ready to go from the beginning,” says fellow comic Sheng Wang, who met and befriended Wong on the San Francisco open-mic scene around 20 years ago (and whose own debut special, Netflix’s Sweet and Juicy, was directed by her). “She’s always been unafraid to share without any filtering, and she was able to say no to opportunities she was not personally interested in doing or that didn’t align with her style, even when a lot of us younger folks in the business were afraid to walk away from opportunities that might give exposure or money.”

Nahnatchka Khan, who hired Wong for the Fresh Off the Boat writers room and later directed her in Always Be My Maybe, says that Wong’s commitment to her authenticity hasn’t faltered under the brighter spotlight. “Some performers put on a persona, but she’s very similar [on- and offstage],” says Khan, another industry collaborator turned friend. “She’s never filtered and will always give you the real.”

Adds Nick Kroll, “What people don’t know about Ali is when you talk to her, she really wants to dig in deep. There’s no small-talk bullshit, and only her dear friends know that part of her. The transparency she shares onstage in a funny way, she shares in real life as an emotional being.”

For Wong, “it all goes back to my instinct and what I find to be funny. I never play to an audience, because if I reverse-engineer it, that’s not where inspiration comes from,” she says. That said, “I could probably do a whole hour on Hello Kitty, but an audience helps tell me what’s too specific and what’s not. That’s why it’s important for me to do sets every night. It’s like doing a table read every day, and that’s the most beautiful part of the process.”

Although her routinely sold-out residencies indicate she has the potential to pack arenas, she continues to pick more intimate venues like theaters. “For me, 3,500 [capacity] just feels too big,” she has said. “You really lose intimacy with the audience.”

Getting her reps in as a comic is part of the rhythm of daily life that she cherishes. “Every single morning I make my kids lunch. I pick them up every day after school. And I go out every night and do a set,” says Wong, who adds that while she may riff on motherhood, she’s not interested in telling jokes specifically about her kids. “I do feel like I’d have to get their permission, and they’re 5 and 7; they still don’t fully understand what I do. And also, there was a lot to complain about when they were infants and it was so hard, but now it’s so corny because I love them so much and love spending time with them, and anything I would complain about would feel cliché and contrived.”

After the Beef press tour, Wong intends to focus on stand-up for the next year and a half, but she remains open to acting, given the right opportunity. “I would have died to be in Fargo or True Detective seasons one or two. Something in those genres scares me a little in a good way,” she says.

“The goal is not to have an incredible career. The goal is to have an incredible life,” she continues. She loves going on tour in part because stand-up remains her “favorite thing in the world” and because at this stage in her daughters’ lives, it provides an almost ideal work-life balance. “Taking kids on the road is so beautiful. It’s the opposite of film and television where I’m just gone all day. It’s a really fun family adventure because basically at night I’m performing, and then during the day, we go on adventures to the children’s museum or the gardens or we see family friends. It’s really cool that they’ve seen so much of America.”

And even if her personal and professional lives continue to evolve in unforeseen ways, Wong isn’t fazed. “Stand-up is a mature person’s game. So I will welcome every single year I have lovingly and tenderly and with so much graciousness and humor because as I grow, so will my stand-up. Everything that seemingly could be devastating careerwise for a woman is nothing but additive for me, no matter what,” Wong says. “I’ve always joked I’m going to live until I’m like a thousand. Whatever happens, I’m in my first trimester of life right now.”

This story first appeared in the March 1 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter