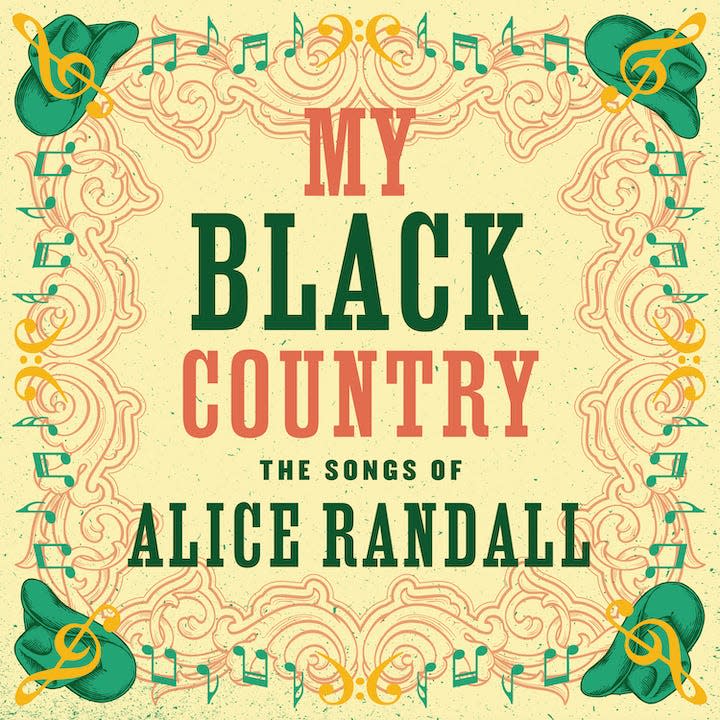

Alice Randall on her album, memoir 'My Black Country,' 'Cowboy Carter,' more

Unbeknownst to Alice Randall, Beyoncé Knowles-Carter had similarly been spending the past half-decade plumbing through the history of Black artistry in country music.

Because of a force that can only be qualified as destiny, the April 9 and 12 releases of Randall's album compilation and memoir, "My Black Country," arrive as Queen Bey's over two-dozen-track "Act II: Cowboy Carter" album occupies Billboard's all-genre Hot 100 charts. She already had a No. 1 pop hit and a No. 1 country chart album from the same release.

Randall has a four-decade-long legacy as one of Nashville's ultimate multi-hyphenates: chart-topping country songwriter, legendary music publisher, award-winning author, and Vanderbilt University's Andrew W. Mellon Chair in the Humanities.

After a decade in Nashville as a Harvard-graduated and "Black punk hippie" (as she describes herself in conversation with The Tennessean), songwriter and publisher Randall co-wrote Trisha Yearwood's 1994 hit "XXX's and OOO's (An American Girl)" with Matraca Berg.

However, 2024 is a different time. Banjo reclaimer and renowned veteran country performer Rhiannon Giddens is featured on both "Cowboy Carter" and "My Black Country." Linda Martell's influence inhabits "My Black Country," and she's a vocal contributor and spiritual influence for Beyoncé's latest album. Between both projects, nearly two dozen Black female artists and creators in the country music space are currently in their artistic primes and being featured in critical and widespread cultural and musical conversations.

'Liberation is an act of art and imagination'

"As much as it is an act related to economics or politics, liberation is an act of art and imagination," Randall says when asked to crystallize what her album and book signify in the larger culture.

Randall's work required the belief in the essence of a deified avatar.

In her case, it was Lil Hardin Armstrong, an American arranger, bandleader, composer, jazz pianist, and singer who was married to Louis Armstrong from 1924 to 1938.

In 1930, Armstrong accompanied her husband as the first Black woman to play on a record that sold a million copies, Rodgers' "Blue Yodel #9" ("Standin' on the Corner").

While briefly surrounded by Detroit's hip, swinging Motown pop and R&B society as a child, Randall's father made her aware of Armstrong and Anna Gordy, Motown founder Berry Gordy's older sister. Gordy herself was already a successful record executive and distributor in the mid-to-late 1950s before Motown's arrival.

Gordy's influence led Randall to open Mid-Summer Music — her own publishing company- two years into her time in Music City — and become an unexpected but valuable fixture on Music Row.

"Brilliance requires taking ambitious risks. So, like my inspiration, Anna Gordy, I had the audacious, self-made determination to become a female creative and executive who was also a songwriter. I also wanted to show and spotlight Black people taking up space in the Nashville-based country music industry, plus support feminine, but feminist, political statements couched in country music," Randall stated in a March 2023 Tennessean feature.

Hardin's influence guides her album and memoir being rooted in "truth-telling" work that occupies multiple levels of an interracial mix of genres, people, and traditions.

The Black first-family of country music

"My work invites Black people back into country's mythologized traditions to construct a not imagined, but rather a real-life first-family of Black creatives in country music that stands performers like DeFord Bailey, Ray Charles, Lil Hardin, (jazz singer) Herb Jeffries and Charley Pride alongside the Carters, Jimmie Rodgers, Willie Nelson, Dolly Parton, Miley Cyrus and more," she says.

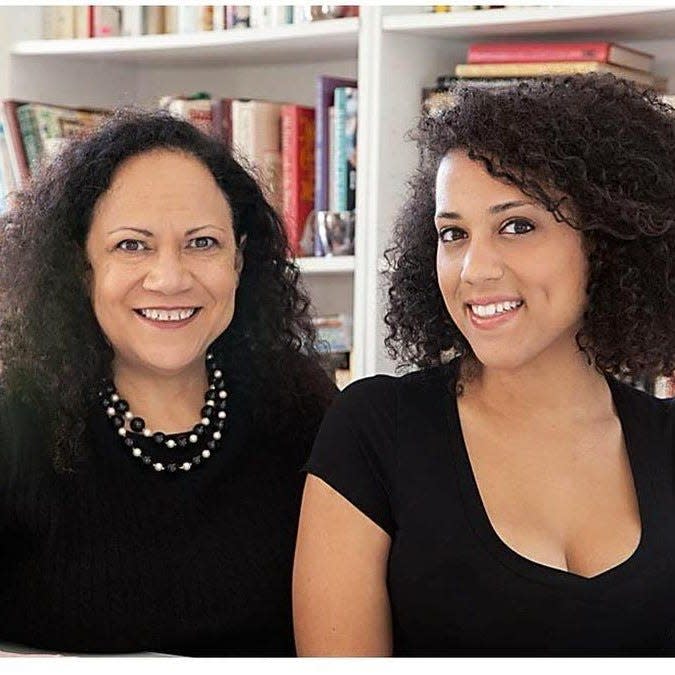

Randall then dives deeper into how events of the past 18 years have impacted her sense of Black family in country music. These include conversations with Giddens, time spent with Pride, her daughter Caroline Randall Williams becoming a respected artist, her work with Vanderbilt University curating collections preserving Dom Flemons and Rissi Palmer's histories and being called upon by Giddens and Allison Russell to create an album compilation reinterpreting her songwriting by Black female voices.

The maddening work of creating and documenting a racially and socially siloed history has weighed heavily on Randall's soul for her four decades in Nashville.

Prior to then, her teenage years were spent in Washington, D.C.'s suburbs, where she was introduced to the music of Glen Campbell, Loretta Lynn, Joni Mitchell, John Prine and Kenny Rogers. There, she lacked a Black community broad enough to engage in multitudes of conversations about those artists' work in comparison to that of acts like Solomon Burke, Roberta Flack, The Supremes and Stevie Wonder.

Couple that with her time at Harvard, which introduced her to the bold complexities of European metaphysical poetry.

"Surviving will give you the blues, grind you down, and make you want to die," writes Randall.

"Country music is hard music for people going through hard times," Randall says. "But it's also a genre that creates art and stories in conversation with my family's Alabama-based Southern roots."

"Adia Victoria ate Easter dinner at my house," Randall also gushes, explaining that the Americana Music Association-nominated singer-songwriter who appears on her album is also a cousin-of-sorts always welcome to sit and eat at her dinner table.

'Is there Blackness that you refused to see and hear?'

In Randall's book, she notes that "country music is three chords and four very particular truths: life is hard, God is real, whiskey and roads and family provide worthy compensations and the past is better than the present."

First, she dates Black country — and now country music's unified — family back through the histories of people like abolitionist Frederick Douglass. He was fond enough of country music's foundational sounds to quote songs in his second autobiography, 1855's "My Bondage and My Freedom."

"Even with complex gatekeeping around knowing its roots, Black country is a big tent with many entry points," Randall says. "My checklist is not a litmus test. It's a likeliness test. It's a way to educate your ears and your eyes. Is there Blackness that you refused to see and hear?"

When asked to contextualize the power of "My Black Country" in conversation with "Cowboy Carter" and American life in 2024, Randall makes a sweeping statement.

"It's different now," she says. "Black genius in country music is no longer hidden in plain sight. Black artists and creatives are consciously rising from history's footnotes to the present's forefront."

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Alice Randall on her album, memoir 'My Black Country,' 'Cowboy Carter,' more