An Imaginary Boy, Reimagined: Lol Tolhurst Reflects on His Life in The Cure

Laurence “Lol” Tolhurst — the drummer/keyboardist who met Robert Smith at age 5 in the West Sussex suburb of Crawley and went on to co-found one of Britain’s most influential bands, the Cure — has come a long way. Twenty-seven years ago, Smith booted Tolhurst from the Cure at the height of their fame, just as they were about to release their most iconic and acclaimed album, Disintegration. Five years later, Tolhurst waged an ultimately losing battle in court against his childhood friend and bandmate over Cure royalties. His life then continued to spiral downward due to a messy divorce, the alcoholism that led to his band firing in the first place, and his struggle to figure out his place in a post-Cure world.

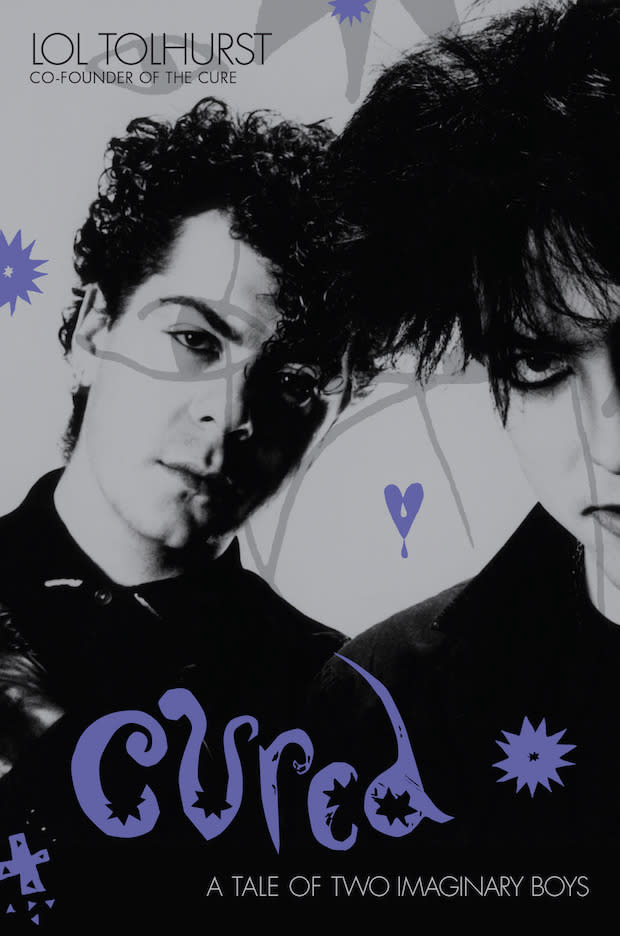

But now, sitting with Yahoo Music at a chic health-food eatery in sunny Santa Monica, California, where he has lived since the early ‘90s, Tolhurst is a changed man: sober for more than 25 years, the proud father of musician/poet Gray Tolhurst, happily remarried, and back on good terms with Smith (with whom he reunited in 2011 for the brief “Reflections” tour comprising the Cure’s first three landmark albums). And Tolhurst reflects on all of this in his compulsively readable new memoir, Cured: The Tale of Two Imaginary Boys, which he’s here to discuss today over a very healthy, very Californian meal of grilled avocado and Tuscan kale.

Cured begins with Tolhurst’s bleak boyhood in dreary Crawley with an aloof and alcoholic father, and climaxes roughly 250 pages and three decades later in California’s Joshua Tree desert, where he experiences a post-rehab, post-Cure, mid-life-crisis epiphany. Along the way, Tolhurst is unflinchingly honest about his journey — as raw, complex, and dark as the Cure’s music itself.

The book is a fascinating chronicle not only of one man’s disintegration (no pun intended) and renewal, not only of two boys’ unique friendship, but also of an incredibly important era in music, when the Cure basically set the template for alternative rock. In true Los Angeles style, there’s already talk of Cured being adapted into a motion picture (Tolhurst suggests Robert Downey Jr. to play himself, and jokes that maybe Sean Penn could reprise his This Must Be the Place role to portray Smith). Until then, check out Tolhurst’s wide-ranging, career-spanning conversation with Yahoo Music.

YAHOO MUSIC: After hearing about the lawsuit between you and Robert Smith, I thought your book would be more bitter. But you are very kind to Robert throughout, and you definitely take responsibility for your actions. You’re also very frank about your alcoholism.

LOL TOLHURST: That’s what I wanted. First, I wanted there to be a story of a friendship, because that’s what it is. Robert is the person I’ve known the longest my whole life, because both my parents are dead now. I’ve known him longer than I’ve known anybody on this planet. I wanted it to kind of be like Patti Smith’s book with Robert Mapplethorpe [Just Kids]; I wanted to put it in that framework. But also I wanted it to be — well, “self-help” is the wrong word, but I wanted it to be a guide to growing up. I’m not ashamed; if somebody has lung cancer, you don’t go, “Oh, you should be ashamed having lung cancer,” or whatever. So no, I’m not ashamed [of the disease of addiction]. I wanted to use [the book] as a tool to help people, and that’s really why it couldn’t be a scandalous drag through the dirt. I know where the bodies are buried, but it’s not going to be in this book.

In the book, you refer to the Cure as your second family that you lost.

Probably my only family, in lots of ways, to be honest.

So you still feel that way?

My relationship with them is definitely still like a family… Every time I see Robert, the first thing that we talk about — probably the only thing that we talk about — is family, because I’ve known him for 52 years and I’m the only person he can talk to about all these other people that nobody knows anything about. I know his whole story from the very beginning. When we get together, we talk about personal stuff, not business or music. So, yes, they’re my family, no matter what.

I was surprised to read that all of you grew up in middle-class, suburban comfort, and that Robert had a particularly nice upbringing, with a happy family life. Where does all of the Cure’s angst come from?

I remember what Beavis and Butthead said: “Why does he sound like he’s crying?” [laughs] It came from being born into Crawley… We had some stability in that way, yes, but we were also growing up in a place that was very anti-anything. That was the dichotomy of living in Crawley, really — that it was the English countryside, but it was a very dangerous, kind of violent place as well. So you mix those two things, and I think there’s a lot of people who identify with that. And the fact that there were a lot of mental hospitals nearby us — we would see [the patients] there and say, “If something goes a little strange, this is how you end up.”

You’re not exactly the ambassador or spokesperson for Crawley.

They’re not going to give me the key to the city any time, that’s for certain. But Crawley shaped our ambition because we wanted to get the hell out of there, and that’s the truth of it. And it’s funny because I know the guys in Depeche Mode really well, and they lived in the same kind of “new town” on the other side of London, Basildon. It’s the same place; it even looks the same! I have this Book of Really Boring Postcards and it has Crawley and then it has Basildon, and they look the same. So I understand completely how Depeche Mode did music like that too. For us, music was our only way out. It was completely a defense against living in a place like that. We knew we were either going to be football stars — Robert had a little bit of a chance at that, because he was quite good — or we were going to form a band and get out of there. Because otherwise… I still know a couple of people who still live there, and it’s very depressing. So yeah, Crawley was a breeding ground because, if you have any intelligence, at some point you notice: “Oh my God, we could end up like that sad guy sitting at the pub.”

So your hometown was key in shaping the Cure’s sound?

I’m absolutely certain of it. A couple years ago I was looking for something on the web, and Google Maps is great, because you can go somewhere [virtually] and look down streets. I was “walking” down some streets I remember from being a child, and I wrote to Robert: “Oh my God, it’s so clear to me now, looking at these places, why we sounded like we did.” Because there’s the gray skies, the clouds and the drizzle, the overwhelming sort of dankness of the place. It’s so obvious why we created the sound that we did.

So are the Cure hometown heroes in Crawley? Not many bands or celebrities ever came from there.

You would think so, wouldn’t you? But a few years ago I was back there, and [original Cure member] Mike Dempsey — he lives like 13 miles from there — he took me on a little trip to go down memory lane, and we drove around some of the old haunts. And we went into the Rocket club, where we first played, there’s nothing of us in there.

What? It should be a Cure museum!

It should be! The only thing that hadn’t changed, though, is that it was still depressing as f—. It was Sunday evening, and everybody was sitting with their half-pints of beer, looking down at the table. It was horrible.

The other takeaway I got from your book, with regards to how your upbringing and environment affected the Cure’s sound, was how bleak everything was in the 1970s in England.

Yes, very true. With this whole Brexit thing now, people don’t remember what it was like back in the early ‘70s. And I do. I remember going to the post office with my mother and seeing the schedule up on the wall, like: “This is your electricity for this week, you get it for three days this week.” There were all these strikes. There was nothing in stores. It was very gloomy, you know? And people have forgotten that. They just sort of see Brussels interfering with them, and it’s just a knee-jerk reaction: “Oh, we gotta leave!” But I remember what it was like before we were in the European market. It’s a bit sad.

Do you predict another musical British invasion happening, in light of Brexit? Great U.K. music seems to come out of dark times.

One can hope. I think you’re right. I think oppression and gloominess definitely makes for a creative melting pot and some kind of crucible to want to do something.

I think the Cure were sort of spokesmen for middle-class, suburban teen angst. That’s my theory why you were so successful in America, the land of suburbia.

Yes, by living here [in Los Angeles], I understand fully why the Cure were very big in California. Although we grew up in a different kind of suburbia, there’s an identification people have here. Yes, [California] is this bright, sunny place, but a lot of the same characters exist. A lot of the same sort of oppressive forces are still there. And that’s what [American kids] identify with, definitely. Plus, we were pretty stylish!

What would you say it is that fans get out of the Cure’s music?

It’s not to do with the sound, per se. I think very much when we started, we made it possible for young men especially to have feelings, and not ignore their feelings. We made that possible for them, even though we didn’t know it ourselves. We made it possible for ourselves first. Therefore, that’s really the thing for me to get across — that it’s OK to be who you are and have that be your driving force, rather than all this other stuff that the world tells you it has to be.

Do you think the Cure was a precursor to emo? I do.

I think people who are into emo think that, yes. It’s like Goth. People say the Cure was a precursor to Goth, but I never really saw that. I understand why people say that, but then when I look at our output, I don’t think of us as a Goth band. I don’t think of us as pre-emo. I don’t think of us as pre-anything.

A lot of people actually think the Cure were the godfathers of Goth. You disagree?

I don’t feel that. I feel we’re the fertile ground that made that possible. I think we gave people permission to have that happen. But even with some of our darker stuff, it doesn’t strike me as Goth, particularly. Saying that, I’m not anti-Goth at all. It’s just that I don’t feel like that’s encompassing it.

There’s this stereotype that music with dark lyrics or themes encourages people to behave violently or suicidally. But I would argue that the Cure’s music has actually helped fans.

I know for a fact that it’s helped people. People have sent us letters saying, “I was going to kill myself, and then I heard your songs, and they explained to me a bit about what I feel.” That’s oversimplifying it, but it’s the truth. To me, the fact that we had those similar feelings ourselves, and were able to channel it into our art, that’s the grace of being able to have that, to put it out there. I know it helped people in that way. Even nowadays with Cure fans, it’s their tribe, and they identify with each other. To share that gives them a sense of identity and makes them healthy. I’ve never thought walking around a Cure show that there was anything other than love and understanding. I’ve never felt any kind of violent or destructive tension… It’s supportive and not aggressive in the slightest.

What would you say is the biggest misunderstanding about the Cure?

That people probably thought we sat backstage crying in candlelit rooms. That’s obviously not the case! We never took ourselves seriously. We took what we did seriously, yes. But if you believe the hype, and if you believe your own fame, that’s not a good place to be in.

How did the peak of the Cure’s fame mess with your head?

I think in some ways, my [getting fired from the Cure] was actually a saving grace for me. Because without that, I probably wouldn’t be alive. I would have gone to the furthest realms of excess, and I’d be dead. So the destruction that I caused, and having it basically alienate me from my family — as in, the Cure exiling me — it’s become my greatest asset. I remember [when I was in the Cure] I was kind of detached from reality, literally, in my rock-star mansion in the countryside. I had no control over anything, because I didn’t care about anything. I was just existing. My world came tumbling down, and it was probably the best thing that happened to me, because it brought me back to me. Robert said to me one night, when we did the “Reflections” tour, “You’re back to who you are.” That’s what a real friend will tell you. And it’s true.

Do you regret the lawsuit — like, if that had not happened, do you think you would have returned to the band after successfully completing rehab?

I like to be like Edith Piaf — I regret nothing. Because you can’t regret stuff. It’s your life. I mean, I do know that in the period, between me leaving the Cure and before I decided the lawsuit would be a great idea, relationships were pretty good still. We were still talking and it was OK. So maybe if I’d gotten myself better then, things might have changed and it might have gone that way. But it is what it is. That’s a horrible expression, really, because it doesn’t mean anything.

Is there any lingering tension between you and Robert, or are you cool now?

I don’t think there’s any discomfort. I think things are all patched up… When I lost the court case, it was a heck of a low, and I probably haven’t said anything about this, but there were a lot of legal bills to be paid, and I ended up having to give away certain rights with the Cure to pay for it. Once that all got paid off, Robert called me up and said, “You should have this all back. This is your stuff.” And he didn’t need to do that. It’s like a legal thing that could have stayed that way. But he always said, “I’m like my mother; I want to keep everybody together.”

You write a lot about your father’s drinking in your book, and about how you got blackout-drunk the very first time you tried booze at age 13. Did you ever put two and two together and think you might be genetically predisposed to alcoholism?

No, not then, because we’re much more evolved here [in the U.S.] in terms of looking at people’s relationships to alcohol and drugs. In England, there was always this sort of assumption: “Oh, just change from drinking whiskey to beer and you’ll be fine!” Because everybody drinks [in England]… It never really occurred to me with my father that that was what wrong with him. Until I got here, I never really thought to myself, “Oh yeah, that’s probably what he died from.”

When you were in the studio and not sober yet, you said Disintegration wasn’t a good album when the band played it back. Most Cure fans and music critics think that is the Cure’s best work! Do you still think that?

No, Disintegration is a marvelous album! It wasn’t that I thought Disintegration was crap, because I didn’t. What I thought was — and this in the book — I was so upset that I couldn’t do anything [in the studio, because I was too out-of-it], so that was me lashing out. Any kind of input I had [in the music] was drifting away; I was clutching at straws and I thought I was going mad. I just thought, “OK, I have to say something,” and that’s what I ended up saying. But it was not what I think at all.

Are there any Cure albums that are difficult for you to listen to now?

No, they’re all great for me to listen to. Disintegration has some wistfulness about it for me, because I know I could have made it even more, I don’t know… But, no. For a long time I didn’t listen to anything, because I couldn’t. But as my soul got repaired, it all comes back and you realize how nice it is, and how wonderful it is, and then you start to feel acceptance and you start to feel proud of what you did.

Some of the gloomier Cure records came out of difficult times for you. Faith and Pornography, for instance, were made around the time of your mother’s death from lung cancer.

Yes, I was the muse of the Cure, really. I say that half-jokingly, but it’s probably true. Like also, during Disintegration, I was disintegrating. Music doesn’t exist in a vacuum, you know.

Does it bother you to see the Cure continue to have success without you, doing things like headlining three sold-out nights at the Hollywood Bowl? I know you went to those shows.

No, it does not bother me at all. I want to be successful too, of course, but I’m happy for them, because I know what it’s taken for them to get where they are. And I like to watch them play live. I’m not that keen, obviously, on some of the newer stuff that I was not on, because I don’t have any emotional attachment to it.

Was it surreal playing in the Cure that first time at the Sydney Opera House, for the “Reflections” shows, after you hadn’t performed with them in 22 years?

It was a surreal experience in the fact that I’m fifty-whatever, and here I am, back with my band — but it was absolutely natural. The second I stepped onstage with everybody, it clicked and it was like riding a bicycle. I know people say that all the time, but it’s true. It felt just exactly the same as always. I looked out and there’s [bassist] Simon [Gallup] in front of me, there’s Robert, and having the three of us like that, I knew exactly what was going to happen. I knew exactly how it was going to go. So did they. What was there to be scared of? Nothing. And it was very lovely.

A “Reflections” mini-tour followed, but you didn’t rejoin the band permanently after that. How come that was just a one-off?

You know, the Cure has always been about going forward. So I’m sure that at some point there’s other things that will happen. But right now I think it’s better to have it as it was, which was a time to reflect. That’s really what I wanted to get across in the book. Yes, I would love to do something again with all the other guys, because Robert and Simon are my lifelong friends. But it doesn’t matter if we don’t for a while.

The Cure hasn’t put out a new album in eight years. Do you think they ever will, with any lineup?

My gut feeling is, there’s life in the old dog yet. [laughs] That’s what I’m gonna say.

Robert has been crying wolf for a long time, claiming over and over, with pretty much every album and every tour, that the Cure are going to retire.

He’s been saying that forever. Forever! But he’s never going to stop. He’s going to stop the day they put him in the ground — that’s the day Robert’s going to stop.

I would love for the Cure to do a similar trilogy show that they did for ”Reflections,” but doing The Head on the Door, Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me, and Disintegration.

Somebody told me the other day that era is called the “Imperial Cure.” I was like, “What? What is that?” That sounds a little pompous for me, but maybe.

Tell Robert you should do an “Imperial Cure” tour!

OK, sure. I’ll set that word in his head. I’ll say it’ll work really well if we do that.

What did you think of Robert saying the Cure’s 2000 album Bloodflowers was part of some sort of unofficial trilogy alongside Pornography and Disintegration?

It’s not how I would have framed it. But he’s welcome to frame it the way he likes.

So now that you’ve had time to reflect on your life in the Cure via this memoir, what is your proudest achievement with the band? What should the Cure be remembered for?

That’s very hard to answer. I think we made some kind of cultural change. I think it’s more than just selling records or filling concerts. I think that we made it allowable for people to be who they were — we made it possible for people to have pink hair, wear black clothes or funny shoes or whatever, and not be chased out of town. People say that to me, and I’m flattered and humbled every time I hear it. There’s at least 500 Goth kids in every city in this country — I know, because I’ve met most of them. It’s nice to have that, because you know, normally I’m like Groucho Marx: I wouldn’t be in a club that would have me as a member. But I think we created our own club, and that’s nice.

Follow Lyndsey on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Google+, Amazon, Tumblr, Vine, Spotify