'Go Ask Alice' Is a Lie. But Bookstores Won't Stop Selling It.

As a teenager in the late 90s and early 2000s, my older sister Sarah struggled with drugs. It began with a prescription to Adderall. “All the positive reinforcement I got when I was on Adderall,” she says, “and then when I wasn’t, all the negative.” Soon she moved to stronger uppers like meth, which she always took in pill form because smoking it made her “feel like a drug addict.” As is often the case, her behavior changed, her grades fell, she quit the soccer team, and she began hanging out with “the druggies.” From my perspective—two years younger, much less adventurous, more nerdy—Sarah’s life frightened me, in part because I knew absolutely nothing about it.

During this time, I noticed a book in my sister’s stuff—a black cover with only a glimpse of a girl’s face, as if she were photographed in a dimly lit dungeon, and the words Go Ask Alice text-wrapping around her eye. I somehow ascertained the premise of the book: the diary of a young girl grappling with drugs. Even by junior high, I’d seen enough “very special episodes” to be cynical and dismissive of these types of stories, but something about Go Ask Alice’s adjacency to my sister, whose problems (while still vague and mysterious to young me) were all too real, gave it the hue and heft of legitimacy.

The book scared me, is what I’m trying to say. But it also provided me with unexpected comfort. That Sarah could find something that spoke to her experiences, that she could commiserate with art in ways she wasn’t able to with anyone else at that time, temporarily relieved me of the guilt I felt over my inability to engage with that part of her problems—to even know the details, let alone do anything to help. And truthfully, I didn’t want to know. Sarah’s life, or at least what I imagined was her life, scared the shit out of me. But that didn’t mean I wanted her to struggle alone. With Go Ask Alice, I hoped that she could learn Alice’s secrets, and Alice could learn hers.

But what if Alice’s secrets weren’t secrets at all? What if they were lies?

Go Ask Alice was published in 1971. It tells the story of an unnamed fifteen-year-old in an unnamed suburb. On July 9, she attends a party at a popular girl’s house, and the kids play a version of “Button, Button, Who’s Got the Button?” in which ten of fourteen glasses of Coke are spiked with LSD, and no one knows which is which. The ones who drink the unlaced soda, we learn, will “baby-sit” the trippers. Alice (as the nameless diarist is often called) does not know about the acid in the Cokes. Unwilling to “appear too stupid,” she goes along with the game until, having consumed one of the tainted drinks, she starts to feel the effects, like “I looked at the magazine on the table, and I could see it in 100 dimensions,” and “I had found the perfect and true and original language, used by Adam and Eve, but when I tried to explain, the words I used had little to do with my thinking.” After dancing and laughing and feeling “completely uninhibited,” she comes down after, I’m guessing, a couple of hours (the only time reference we get is “after what seemed eternities”), learns that she’s just tripped on LSD, and goes home elated.

Then, literally five days later, this girl who has never tried drugs before, whose first experience with them was LSD that she wasn’t aware she was taking, is injecting speed into her arm with a needle. She’s also trying something called a “torpedo,” which Google tells me is a mix of marijuana and crack (!). But then her grandfather suffers a heart attack, sending Alice into an existential crisis, and she vows she “won’t ever again” use the drugs she started, like, two weeks ago. She avoids her new druggie friends, using her grandfather’s brush with death as an excuse. By August 2, she sounds like a grizzled veteran; after her grandmother “insists” that she get out of the house, she writes, “I guess I’ll go with [Bill, the boy who introduced her to torpedoes and speed] but I’ll just baby-sit if he wants to trip.” But then of course she doesn’t quit; in fact, she drops acid that very night, and even has sex for the first time too! By October 17, she’s dating an older dealer who “restocks my acid supply and gives me enough grass and barbs to last me until I see him again,” and selling “ten stamps of LSD to a little kid at the grade school who was not even nine years old, I’m sure.” By December 3, Alice has run away to San Francisco and tried heroin. The following winter, Alice is dead.

Um, a couple things. First of all, the idea that someone’s gateway drug experience is being unknowingly dosed with LSD is absurd. If you didn’t know you were dropping acid, it would not be a good trip, and you would probably swear off all drugs forever. Secondly, acid doesn’t last for a couple of hours hanging in your friend’s basement. There’s no way Alice would return home later that same night totally fine, especially given that, based on the trip she described, she must have taken a fair amount. Moreover, her descent into torpedo-smoking, drug-peddling, dealer-banging runaway happens way, way too quickly. It simply doesn’t ring true. Hardly any of the writing feels wholly authentic. For a teenager like my sister, who sought commensurate camaraderie, authenticity was the whole game, even though she suspected the publishers may have “elaborated on” the true story. Does the narrative recounted above sound like the story of a real teenage girl? Or does it sound like the uninformed paranoia of a worried parent?

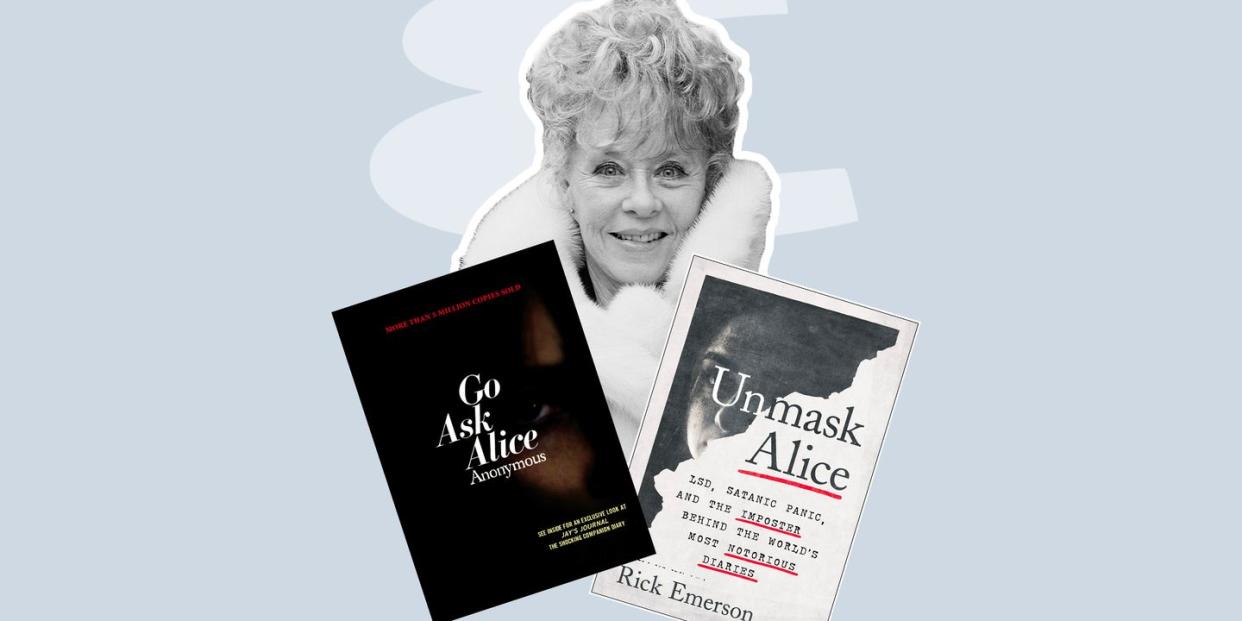

To answer these questions, enter Rick Emerson’s Unmask Alice: LSD, Satanic Panic, and the Imposter Behind the World’s Most Notorious Diaries, a fascinating new book that exposes the fraudulence behind Go Ask Alice and Jay’s Journal, another “real” diary about a kid who succumbs to witchcraft. Emerson’s subject is the person behind these books: Beatrice Sparks. You may recognize this name if you’ve read Jay’s Journal; even though the author is “Anonymous,” it was “edited by Dr. Beatrice Sparks, who also discovered Go Ask Alice.”

So who was Beatrice Sparks? According to Emerson, she wasn’t a doctor or an editor, but rather an enterprising writer and member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from rural Utah. Born in 1917, Sparks (née Mathews) dropped out of school at seventeen and headed for San Francisco. In California she met LaVorn Sparks, married him six weeks later, and eventually had two children with him. The couple moved to Texas, where LaVorn opened a dry-cleaning business while Beatrice stayed home with the children and began to try her hand at writing. LaVorn got lucky investing in oil, and the Sparks family found financial stability.

Emerson intertwines the story of Beatrice Sparks with brief forays into the history of LSD, Nixon’s war on drugs, and, later, the Satanic Panic. As Sparks vies for whatever writing opportunities she can—including writing an advice column in a Joseph Barbera comic book, during which she received more letters seeking counsel than was possible based on sales (meaning, Emerson suggests, she mailed in the questions to herself)—we learn about the fate of broadcaster Art Linkletter’s daughter Diane, who jumped out a window to her death. Convinced it was LSD’s fault (she’d told the last person to see her alive that she’d taken some), Linkletter went on a public campaign against drugs, including meeting with Richard Nixon. But because no LSD was found in her system (the autopsy didn’t check for it), Linkletter came to believe that his daughter “was having involuntary flashbacks,” and that “it was in one of these flashbacks that she killed herself.”

Linkletter, in addition to being the genial host of People Are Funny, which became the inspiration for Kids Say the Darndest Things, endorsed numerous products with his celebrity, including the Family Achievement Institute, a multi-level marketing scheme involving vinyl albums of “parenting advice, uplifting stories, and bland spiritual wisdom.” Sparks was hired to write some of these pieces, and even though FAI was a “colossal flop,” she now had an in with Linkletter, who was influential and involved in myriad business interests. Shortly after the death of his 20-year-old daughter, it was to Linkletter that Sparks pitched her idea for what eventually became Go Ask Alice. She signed with Linkletter’s literary agency, and the book sold to Prentice-Hall. She was 53.

When speaking to my sister about the book’s veracity, she points out something ironic about it: “I feel like the people who were going to do those kinds of drugs, a book wouldn’t have stopped them.” I think she’s right. Sure, there are probably a handful of kids who read Go Ask Alice and vowed to remain drug-free, but the people affected by Sparks’ work the most were not the ostensible audience, but their parents and politicians. A friend of mine told me that their mother, who never cared much about the art they consumed, positively flipped out when she saw a copy of Go Ask Alice in her child’s hands and forbade them to read it. The War on Drugs is like a macrocosmic example of this type of authoritative overreaction. I’m reminded of a line from another diary, this time a fictional one: in Chuck Pahlanuik’s novel Diary, there is a refrain: “What you don’t understand you can make mean anything.”

Little is known about the source material behind Go Ask Alice. Sparks’s own account of obtaining the diary, according to Emerson, “changed with every telling.” Emerson provides a probable inspiration: a young girl staying at a Mormon summer camp at Brigham Young University. Sparks had a long history of presenting herself as a psychologist or a youth counselor, though she had no degree or license. Despite this, her unverified claims were printed in numerous stories about her. A worried counselor in the camp called Sparks when a girl Emerson calls Brenda (she doesn’t want her real name printed) suffered a breakdown. Sparks, Emerson suggests, spoke to the girl and then kept up with her for some time afterward.

The story behind Jay’s Journal is much clearer, and much more horrific. Alden Barrett was a smart but difficult kid raised in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Utah. He struggled with depression, didn’t fit in his conservative community, and stole pills from his father. Perpetually at odds with his parents, Barrett briefly ran away from home to San Francisco, just like Sparks and Alice, before returning home and trying to kick the drugs. After a relapse led to an arrest, Barrett met and fell in love with Theresa, a classmate one year older than him. When her parents discovered Barrett’s lurid past, they forced the couple to split. Distraught over the breakup and his jealous paranoia that Theresa would get back together with her ex-boyfriend, Barrett shot himself with his father’s gun. He died in 1971, the same year Go Ask Alice hit bookshelves.

For the last six months of his life, Barrett kept a journal. It contained 67 entries. In 1977, Barrett’s mother read an interview with Sparks about her role in bringing Go Ask Alice to millions of readers. Barrett’s mother sent Sparks the diary, which became Jay’s Journal. Sparks’s version, however, contains 212 entries taking place over eighteen months—and, worse, suddenly Barrett (as Jay) isn’t merely struggling with mental illness; he’s a full-on Satan worshipper, replete with rituals, sacrifices, orgies, demons, animal mutilations, and all manner of morbid and melodramatic miscellany. Barrett’s diary never mentions any such nonsense, but that didn’t stop Sparks from publishing it as the truth, warning parents about the dangers of Satanism.

That Go Ask Alice played a part in the disinformation campaign against drugs in the 70s and beyond, and that Jay’s Journal contributed to the Satanic Panic of the 80s, are incontrovertible facts. That they are both based on tiny kernels of reality, but are mostly the fabrications of a religious woman in her 50s and 60s, also seems pretty inarguable. Just read the books; the parts dealing with drugs or witchcraft (or, in other Sparks titles like It Happened to Nancy or Annie’s Baby, AIDs and teen pregnancy, respectively) would be laughable if their consequences weren’t so dire. It’s hard to believe that anyone bought into this stuff—particularly the press, which welcomed both books with glowing recommendations, including banal hyperbole like, “A book that all teenagers and parents of teenagers should really read,” from the Boston Globe. But then I remember myself as a kid, watching my sister struggle. I didn’t know the details of her world at all, so any source claiming to let me in on the secrets would probably have convinced me. Had I read Go Ask Alice as a teen, I might have worried myself sick that Sarah was going to sell acid to babies and die in a year.

But that didn’t happen. Instead, the less dramatic but more common things occurred: Sarah eventually kicked the meth habit via some major life changes, including a move to a new state and a halfway house. The trouble, however, is never really over. She will struggle with addiction for the rest of her life—warding it off, keeping it at bay—a battle about which Go Ask Alice has nothing to say.

These books are untrue, and any subtle or unsubtle hint otherwise is patently dishonest. The copyright page of Go Ask Alice states that it’s a work of fiction, whereas Jay’s Journal, by means of not staking a claim one way or the other, still purports to be true. Go Ask Alice has sold over five million copies; meanwhile, Simon & Schuster recently published a 50th anniversary edition. In the YA section of Barnes & Noble, you’ll find a bunch of Sparks’s books, all designed with similarly sinister covers. The publishers are still profiting from these lies.

This is why the debate over who gets to tell stories is so vital. It isn’t about limiting the creativity of storytellers or challenging anyone’s empathetic capabilities. Rather, it’sabout what can occur when someone who hasn’t experienced something writes about it, and when readers who also haven’t experienced it read that writing and believe it. The mistakes a misinformed narrator can make are often ones they aren’t even aware they’re making. Beatrice Sparks didn’t know what it was really like to struggle with drugs, and probably felt that her end (warning children off drugs and sin) justified her means. But her ignorance inadvertently contributed to a culture that was too frightened of what it didn’t understand to productively deal with it. The war on drugs did more damage than good, focused as it was on eradicating symptoms while neglecting the disease. Drug use wasn’t the problem; systemic oppression, poverty, depression, sexuality, gender identity, abuse—those are the reasons there was such a high suicide rate for teens in the 70s and 80s. It was not because Satan was on the hunt.

“It’s like everything we were ever told turned out to be bullshit,” Sarah says. Lying to children, while perhaps temporarily effective, eventually turns them distrustful once the deception is revealed. A messy, hard-to-explain truth is always preferable to a tidy deceit.

The publishing industry likes to posture as if it has a no-tolerance policy regarding dishonesty from writers, but somehow, the publishers themselves never seem to take any blame. Consider Kaavya Viswanathan, a Harvard sophomore whose debut novel, How Opal Mehta Got Kissed, Got Wild, and Got a Life was pulled from shelves in 2006 because Viswanathan copied from Megan McCafferty’s novels Sloppy Firsts and Second Helpings. Or Jonah Lehrer’s Imagine: How Creativity Works, which suffered a similar fate when it was revealed that Lehrer had attributed quotes to Bob Dylan that he’d never actually said. The ensuing scandal unearthed other instances in which Lehrer had published dubious work, including some self-plagiarism. And who can forget James Frey, the author of A Million Little Pieces, who sat in front of Oprah and millions of viewers while she lambasted him for embellishing and lying in his memoir?

But what are we to do with books that have been on bookstore shelves for decades, sold millions of copies, and greatly influenced not just publishing but culture in general? What happens when we discover that stories purported to be true turn out to be lies? Should those books remain available to readers? Can the damage ever be undone?

Stories are effective weapons, so our usage of them must come with responsibility. This is particularly true of the stories we tell to young people. And if we aren’t more actively selective about who is doing the telling, if we don’t continuously consider the possible ramifications of false authority, we play a part in the problem we’re hoping to fix. Millions of people have read Go Ask Alice, many of them kids who picked the book up because they were dealing with problems their communities didn’t talk about or believe in or understand, and for lack of options, they grabbed for what they could. They had no one else to ask.

You Might Also Like