The Assassin Next Door: He Tried to Murder Reagan So Jodie Foster Would Love Him & Now Lives 'Symptom-Free' with His Mom

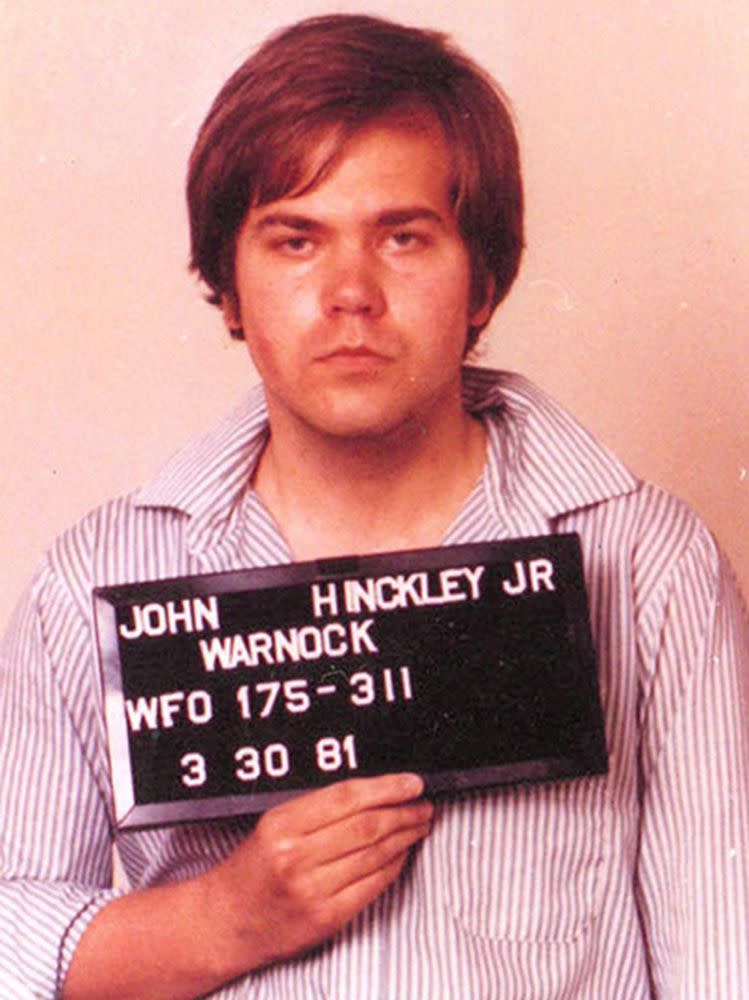

Thirty-eight years after John Warnock Hinckley Jr. attempted to assassinate President Ronald Reagan in a mad bid to impress Jodie Foster, he is — mostly — a free man. Many people in the Virginia town where he lives with his mother and older brother don’t even recognize him.

“No one gives me a second look,” Hinckley, now 63, told a psychiatrist in a recent evaluation.

Last March, Hinckley struck up a conversation with a neighbor walking her dog in their gated community in the Williamsburg area. He introduced himself as “John.” When he wanted to connect with her again, he and his social worker decided it would be a bad idea for him to knock on her door or leave a note. Instead, he sent a letter asking her out for coffee.

He signed his full name, but when the woman realized who he was, she called the police and they contacted the Secret Service. (Hinckley’s social worker later acknowledged Hinckley’s treatment team might have pressed him a little too hard to be social. He has since been more cautious approaching women.)

Hinckley left Saint Elizabeths in Washington, D.C., three years ago following a 34-year hospitalization — a release that Reagan’s family strongly opposed.

But his doctors and therapists agreed that he has long been mentally healthy, his depression and psychosis long in remission, and his attorney argued he should be granted a life outside of the hospital.

“He’s doing exquisitely,” Hinckley’s lawyer Barry Levine said in court in November. The evaluations, he said, “find no mental disease. They find no danger.”

“He can live a normal life like any of us,” Levine told the court. “That’s the objective.”

In 2016, the federal judge overseeing Hinckley’s case agreed to his discharge, with restrictions. He did not travel far outside D.C., settling with his family in his mom’s two-bedroom patio home in a gated resort and residential community in Williamsburg. (His father, a wealthy oil executive, reportedly died in 2008.)

Hinckley’s day-to-day life is like that of many other men in their 60s: He has arthritis, high blood pressure, a bad back and a right knee that has been giving him some trouble. He drives his mother to doctor appointments, goes grocery shopping, does laundry, cleans out the gutters. He works or volunteers three days a week, as required by the court.

“They’re living a quiet life,” says Jack Garrow, 87, who lives about five houses away on the same street. “We don’t see him — I don’t even remember the last time I saw him.”

Hinckley was not set free, not entirely: His September 2016 release came with a list of 34 conditions, one of which was that after 18 months he would undergo full psychiatric and psychological evaluations and another risk assessment.

A review of these records — which were filed in federal court in March, obtained by PEOPLE and first reported by the Los Angeles Times — as well as interviews with eight community members provide this portrait of Hinckley’s life now.

He is the rarest kind of rarities: a living, would-be presidential assassin who is out and about in the world.

“My name is well known,” he explained to a court-appointed psychiatrist during an evaluation in October, “but not my persona.”

Forgiving but Not Forgetting

It all started with Taxi Driver.

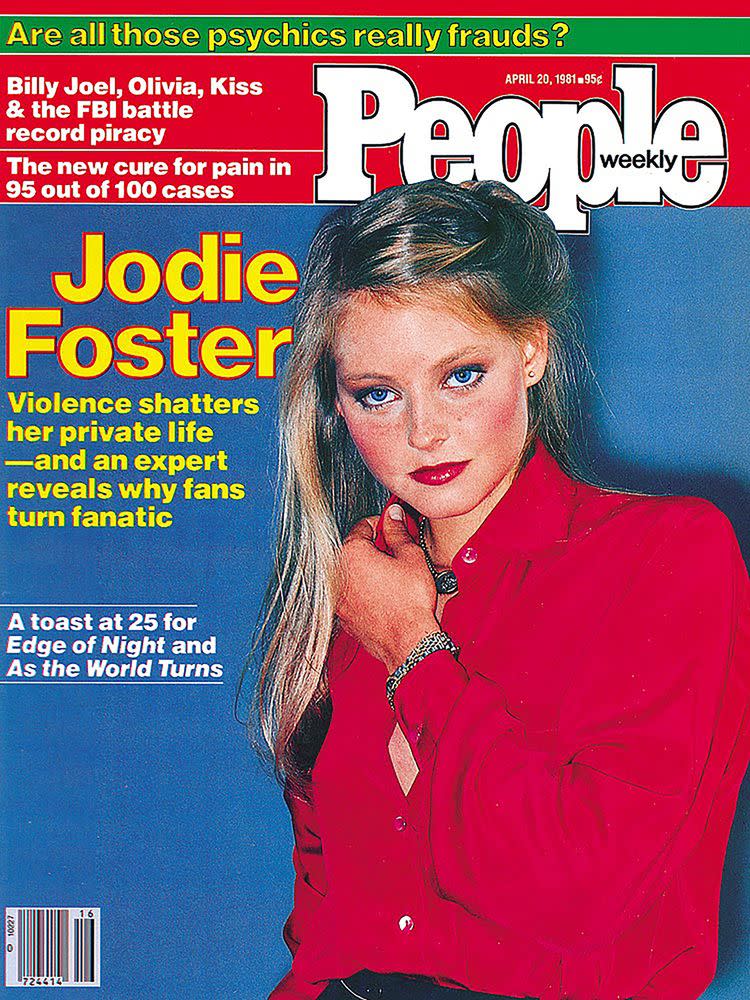

Hinckley saw the 1976 Martin Scorsese drama, starring Robert De Niro and Foster, more than 15 times. Hinckley became obsessed with Foster, who played a teenage prostitute with whom De Niro’s character, Travis, became fixated as he descended to vigilantism.

Hinckley, then a 25-year-old college dropout from Texas, modeled himself after Travis, gathering the same arsenal and devising the same plot to kill a politician. He stalked Foster, repeatedly driving to Yale University where she was a student. He called her dorm room numerous times and recorded their conversations.

In his hotel room on the day he shot President Reagan, on March 30, 1981, Hinckley left behind a love letter for Foster.

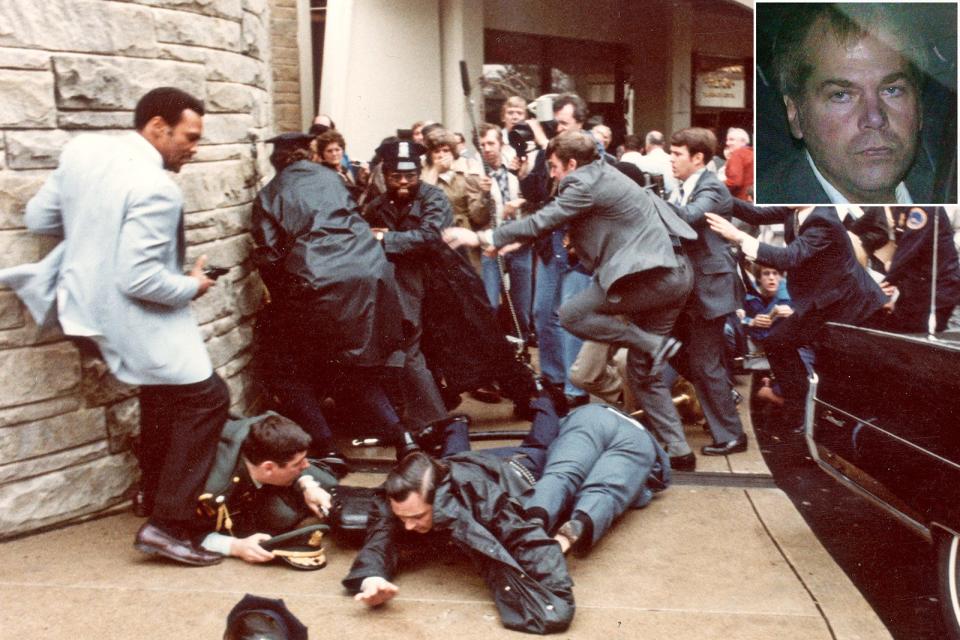

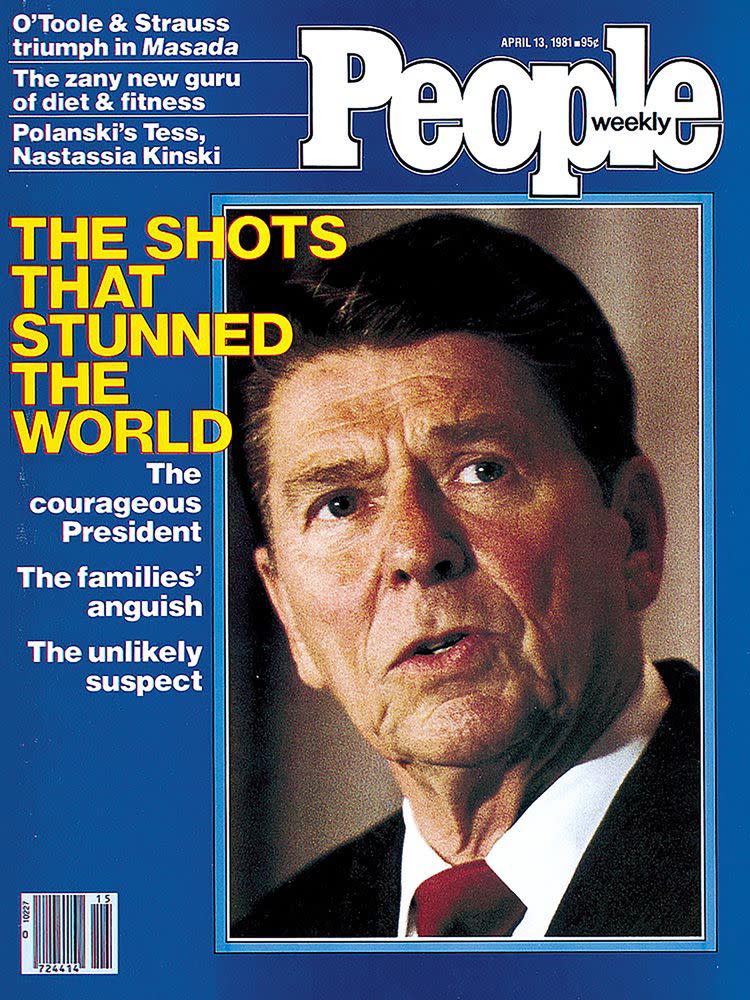

Then he opened fire six times outside the Washington Hilton. A bullet punctured Reagan’s left lung and another struck Press Secretary James Brady in the head. A Secret Service agent was shot in the stomach and a police officer was shot in the neck. Brady died in August 2014 in what the coroner’s office said was a homicide because of his injuries in the assassination attempt.

During Hinckley’s seven-week trial, defense psychiatrists testified that he was extremely mentally ill, driven by an internal frenzy to kill the president and magically gain Foster’s love, the Washington Post reported.

The prosecution argued that Hinckley knew what was he was doing and asked the jury to hold him responsible.

Jurors disagreed and found Hinckley not guilty by reason of insanity. He was committed to Saint Elizabeths Hospital in D.C.

In the subsequent 34 years, Hinckley underwent intensive treatment. He was prescribed an antipsychotic, Risperdal, and the antidepressant Zoloft, which he continues to take. With time, he was permitted supervised visits with his family and then gradually was given more and more privileges. He eventually went on numerous unsupervised visits without incident, living with relatives for days at a time before returning to Saint Elizabeths.

During these trips, he began working with his current, tight-knit treatment team. In December 2014, Saint Elizabeths proposed in a letter to the court that Hinckley be transitioned from 17-day visits with family to full-time leave. Three years ago he left the hospital. He was barred from contacting the Reagan family or Foster and he and his family can never speak to the media. (His attorney did not return PEOPLE’s request for comment for this article.)

“Mr. Hinckley has displayed no symptoms of active mental illness, exhibited no violent behavior and shown no interest in weapons,” United States District Judge Paul L. Friedman wrote in July 2016. “The court finds by a preponderance of evidence that Mr. Hinckley presents no danger to himself or to others.”

In a July 2016 post on her website, Reagan’s daughter Patti Davis said she was not surprised that Hinckley had at last been let out.

“But my heart is sickened,” she wrote. “When my father was lying in a hospital bed recovering from the gunshots that nearly killed him, he said, ‘I know my ability to heal depends on my willingness to forgive John Hinckley.’ “

“I, too, believe in forgiveness,” Davis continued. “But forgiving someone in your heart doesn’t mean that you let them loose in Virginia to pursue whatever dark agendas they may still hold dear.”

Davis is not the only one who is suspicious of Hinckley, despite the medical consensus on his recovery. Local police, however, stress to PEOPLE that they have had no problems with him.

Three times the Secret Service has contacted Hinckley’s social worker about him since he left the hospital, but none of them were about a possible threat.

Last year, agents were alerted after his letter to the woman he had met that March, and they in turn contacted the social worker. They reached out again when Vice President Mike Pence was speaking in Virginia and they wanted to know Hinckley’s whereabouts. The third time was after Hinckley called 911 in August when his mom fell and broke her hip in the middle of the night.

When he was first released, Hinckley was “quiet and shy,” his social worker said, according to the court records. But he worked hard, made steady, positive progress and exceeded all the goals his treatment team set for him.

His social worker described him as “a continuing success story.”

Still, neighbor Joe Mann, like Reagan’s daughter, is skeptical. He says he also forgave Hinckley because it was the “righteous” thing to do — “but forgetting is putting everyone in danger.”

“The gentleman tried to kill the president. He put Jim Brady into a life of pure hell the way he wounded him,” says Mann, 77, who hasn’t seen Hinckley at all in the last few years. “Jim died living a fraction of the life he would have lived.”

Conservative talk radio host Andrew Langer, 48, says his teenage children are often at the same bookstore which Hinckley sometimes visits. He warned his kids to leave if they see anyone doing anything suspicious.

“You have the uncomfortable conversation about who this is, why he is here and why he is able to roam about,” Langer tells PEOPLE. “The question that a lot of folks are wondering about is: Is he really well enough to be out on his own?”

Realtor John Womeldorf says he sees Hinckley taking walks around the neighborhood, usually wearing a baseball hat.

“He seems to want to stay to himself — I just leave him alone, and I think everyone else does as well. Most people I don’t think would even recognize him,” says Womeldorf, 56.

Whenever Womeldorf shows a home in the neighborhood, he tells his clients that Hinckley is a resident and points out his house.

“You never know how people might react,” he says. “I’d rather they know it up front and be aware of it.”

A Small Life but Hope For More

A lot is forbidden to Hinckley.

He is a musician and songwriter but cannot perform in public and cannot share his music online — even anonymously — without pre-approval from his Williamsburg treatment team. He cannot earn any money from his music or have any interaction with people who hear or comment on it. The same restrictions apply to his paintings and photography.

He cannot have accounts on Facebook, Twitter or YouTube and cannot Google himself or his crimes.

But his life is not empty. He lives with his 93-year-old mother, his brother and his cat, named Theo, whom he adopted from the Humane Society. He plays guitar and the keyboard and his music therapist described his lyrics as “thoughtful and sweet.”

He volunteered at the local Unitarian Universalist Church, where he built birdhouses and gardened. But he wasn’t very good at either task. He loves books, so church officials instead showed him how to sell donated copies online.

Les Solomon, a past president of the church, mentored Hinckley and invited him into his home where Solomon explained how to input the books, price them and taught Hinckley customer service and business skills.

“I was learning along with him,” says Solomon, 76.

Hinckley did so well that he soon took over the church’s online book sales, then created an Amazon account and started his own online used book business. Because profit margins were low on books, he obtained a consignment space and began selling antiques, Solomon tells PEOPLE.

“He’s doing wonderful,” Solomon says of Hinckley. “I’m very pleased.”

He says Hinckley, despite the fixed image of him from the assassination attempt nearly 40 years ago, is actually a “quiet, caring person” and a wonderful conversationalist.

Hinckley’s therapist’s goal is to keep him medicated and to prevent him from becoming isolated and depressed. He keeps a daily log, per the court’s orders. His team calls him predictable and reliable.

“John does everything we ask him to do,” his forensic psychiatrist said.

In Williamsburg, the Hinckley family has paid out of pocket for his continued mental health care, including group and individual psychotherapy, psychiatry and music therapy. The court mandated that he drive to D.C. monthly to meet with a psychiatrist at the hospital.

Someday, when his mother is no longer able to live in her home, Hinckley and his brother hope to move into an apartment together. Because he’s done so well adhering to the court’s conditions after his release, the judge has lifted a few restrictions, including approving a potential change in his living situation.

Hinckley can also now drive 75 miles from his home, allowing him to pick up his sister at the airport in Richmond or go to a concert in Newport News.

Six months ago, Hinckley told a psychiatrist that this is the happiest — the most content — that he has ever been. He feels fantastic. “I’m symptom-free,” he said.

As the two spoke, Hinckley “looked out the back window and said, ‘It is so peaceful, just look at what I have here.’ “

He added: “What a life.”