Author Francesca Royster on Black country music fandom in the modern era

The revolutionary fervor surrounding Black country music artists has achieved an unprecedented fever pitch. Though African-American country music fans may see more of themselves reflected under spotlights, they are still small in number in audiences in spaces and venues showcasing Black artists.

The tenor of this moment was set in June 2022 when Country Music Association CEO Sarah Trahern told The Tennessean before CMA Fest, "From traditionalists and modernists to Americana, I'm proud that country music's the biggest tent."

However, though it's the biggest tent, striving for solving for feeling like it's perpetually the most welcoming environment is another story altogether.

Ten years have elapsed since Francesca Royster -- a Professor of English and Chair of the English Department at Chicago's DePaul University -- attended the 2014 edition of the mainstream country music beloved Windy City Smokeout Festival.

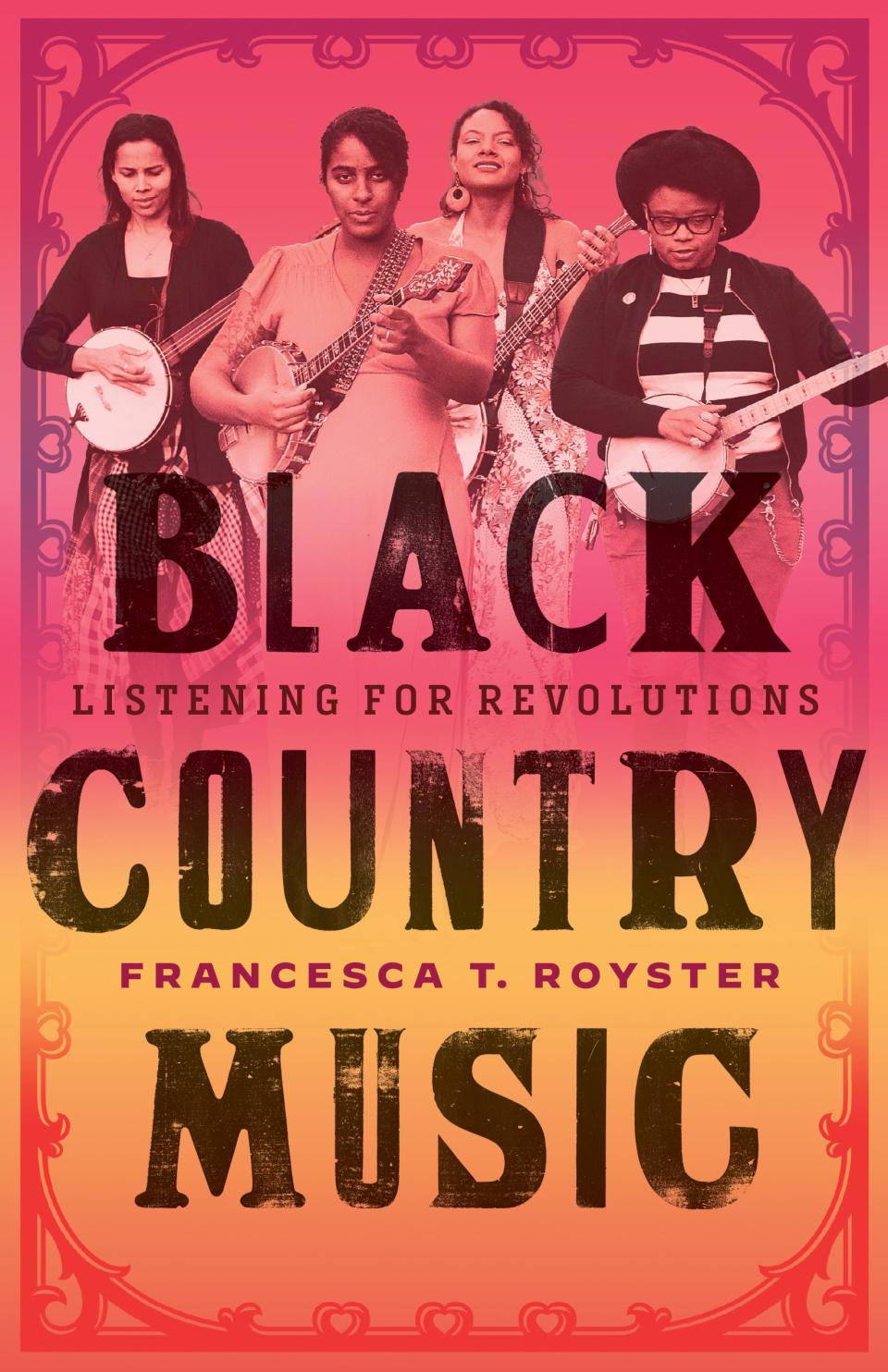

A decade later, she's the author of the 2022-released "Black Country Music: Listening for Revolutions," a compendium that studies the history and future of African-American achievement in the genre.

Her year-old book's introduction discusses her wandering around the 20,000 attendee festival, attempting to ask the few other Black attendees why they enjoyed the genre and were attending the event.

"I'm just here for the barbecue," answered one person.

Birkenstock-clad, dreadlocked and looking very "professorly," Royster describes her look as "smartly dressed for comfort," which, at a country festival at the height of the "bro-country" era, certainly did not see her fitting in well, if at all.

"I didn't organize myself smartly. I was a fan without a press badge, just asking questions of the few Black and Brown people I saw."

Royster reveals a fact about the event not present in her book.

"I was asked to leave [the Windy City Smokeout]. I was polite, but because I was taking notes [without press access], it was evident that I wasn't just a fan having fun."

A conversation about Black music, Black people and Black comfort in modern country music begins best by hoping that a time wherein a Black fan of the genre needn't "organize smartly" by having to wear a costume or planning to offer photographic or written journalism to support the proceedings occurs quickly.

Do Black mainstream stars deny country's Black stars greater renown?

Moreover, the conversation can be framed by considering that a glass ceiling regarding Black success in the space has been artificially placed on the genre -- possibly in a manner most unaware -- by the genre's all-white ruling class of final decision-making executives.

1995-2005 marked an era where popular music sold more physical units than at any other time in the music industry's history. The plethora of southern and midwestern Black artists who achieved success is intrinsic to this movement.

Southern and midwestern artists, being marked by history as the most famous artists of all time, worked incredibly in favor of predominantly southern and midwestern population-based country music

Ever wanted to supersede Charley Pride's 29 No. 1 singles in country music? Well, add the era's dominant superstar bookends -- Charleston, South Carolina-born Hootie and the Blowfish frontman Darius Rucker and St. Louis-born rap star Nelly -- to country music by 2010. By 2020, both artists' peaks in country music (Nelly's collaboration with Florida Georgia Line for "Cruise" is a 14-time platinum seller, plus Rucker is a 10-time chart-topper and member of the Grand Ole Opry) set them among the genre's most peerless icons.

With Nelly's pairing with Florida Georgia Line, a fascinating transferrence emerges under the lens of Royster's scholarship. The line where white performers once used blackface minstrelsy to portray Black culture dissolves. Instead, what appears is a place where white acts, sans makeup, routinely achieve something both authentically Black and authentically country.

"Appropriation has become an everyday part of how America addresses Black culture," says Royster. "Therefore, the inclusion of Blackface minstrelsy in conversations about white performers appropriating Black styles to achieve success is important."

Artists not named Pride, Nelly, or Rucker attempting to reach the types of acclaim that the trio have in the past sixty years are troubled by the idea that they're double-bound -- according to Royster -- by having to "play catch up" to legendary Black artists by having to reclaim roots once soaked in their own culture that are now "expertly" also held in white hands.

Royster feels that African-American country music fans gravitating towards the two-decade-long work done in the country-adjacent Americana genre makes sense because, as she highlights, the allyship and historical re-framing happening in that space as fostering voices inspired by "looking backward to fix the future."

Country's mainstream spaces are defined less by historical re-framing and more by a commerce-first "what have you done for me lately" attitude driven by charts, concerts, festivals, plus radio and streaming airplay.

Royster does not see similar movements occurring in these areas with a comparable organic groundswell of support.

Can Black country fans ever entirely fit comfortably in predominantly white spaces?

The fan-level trickle-down is fascinating to consider.

Royster, when framing her thoughts on this notion, draws them along lines similar to ideas formed in Billboard and Country Music Association research released in 2011 (adjusted for inflation) which notes that 52% of the genre's fans are generally white female college graduates earning six figures who are married in their mid-30s with two children and live in $300,000 homes.

By comparison, according to 2013 research (adjusted for inflation), the average Black female American resident earned 13 cents less to the dollar and was nine percent less likely to graduate college, 50 percent less likely to be married and 25 percent less likely to own a home.

"The average Black female country music fan has to walk a narrow path to mirror the genre's standard. She has to achieve a flawless, beauty queen level of attractiveness and presentation," says Royster.

"To fit in, we're supposed to be wearing an envious level of blinged-out country couture -- belts, buckles, boots, hats, you name it -- and whooping it up with our [predominantly white] friends, like we're at a bridesmaids party. Of course, if you're Black and don't look like that, you can make eye contact and smile, but it's intimidating to feel like you're a part of the culture, for sure."

Royster discusses what playing October 2008's Windy City Smokeout predecessor, the Chicago Country Music Festival at Soldier Field Parkland, felt like for current CMT TV correspondent and Apple Music Radio Color Me Country host Rissi Palmer.

"Rissi looked out at the crowd and felt the discomfort and isolation of what it was like to be Black and not fitting stereotypes in that space."

What are sustainable methods to ensure Black fan comfort in country music?

Country music and related genres are a top-down space where .1 percent of stakeholders hold the greatest controlling interest in the broadest movements garnering the most enormous interest for almost 99.9% of the fanbase.

Thus, the idea that Mickey Guyton can have four Grammy nominations and perform on the Grammy Awards stage, while Rucker, Jimmy Allen, Blanco Brown, BRELAND, and Kane Brown can have No. 1 hits, Allison Russell can win the Americana Music Association's 2022 Album of the Year award -- plus also having multiple Black acts appearing on the Grand Ole Opry is important.

However, the Academy of Country Music and Country Music Association -- by not more fully acknowledging the top-tier, prime-time, wholesale movement of Black art at the genre's pinnacle -- now appear like holdouts, waiting for Blackness in the craft to crack an artificial glass ceiling.

Canadian musicologist Dr. Jada Watson's 2021 research noting that BIPOC artist representation -- including airplay, CMA and ACM Awards nominations, record deals and charting singles -- makes up less than 4% of the commercial country music industry is "shocking," says Royster.

Royster chuckles with an annoyed tone when asked to dig deeper and contemplate solutions after the "somehow" that she throws out, exasperatedly, regarding changing that figure.

She correctly highlights the success of the allyship for Black artists practiced by Brandi Carlile and Jason Isbell in Americana. She also notes the work done by CMT and Philadelphia's nationally-renowned independent radio station WXPN in aiding the platforming of the roots and pop-aimed Black Opry touring organization.

Does the adoption of progressive idealism govern Black country's future?

Regarding the flawed, yet fighting mainstream country space, she's heartened by the success of Black male No. 1 artists. But she's also "fearful" that their success represents a larger quota for Black success similar to the "one and done" idea that appeared to govern commercial country music during eras where Pride and Rucker achieved chart-topping status.

But ask her to dig to her most authentic truth -- that of being a Black queer scholar with a Ph.D. earned in 1995 from the University of California at Berkeley -- and a new, nuanced and dynamic answer for how Black art can inspire the most significant number of Black fans of country music fans becomes apparent.

"Ruinage, fugitivity, and radical utopian arguments from the forefront of modern African-American and queer studies curriculums are all about creating strong underground movements of freedom, collaboration and connection that eventually go mainstream and promote freedom in all spaces," says Royster.

"Empowering marginalized spaces to assess country music's mainstream and developing integrity-driven strategies for integration is key. While Black faces in the public eye are necessary, their work already drains them of the resources required across all levels of the industry."

In an ideal world, Royster imagines synergy between marginalized voice-driven, left-of-center organizations blending with more center-right-leaning mainstream country music to arrive at a middle ground where the genre reflects a vast array of influences, people and sounds.

For Royster, she turns to her 2022 text as her best, most comprehensive answer for all questions she's answered -- and will continue to answer.

["Black Country Music"] is evidence as a weapon, available at people's fingertips for teaching the country music establishment how to engage with a diverse country music fanbase."

"I'm still waiting for that friendly, comfortable group of Black country music listeners at all these events. Instead -- as it has been for the past decade -- I still feel self-aware and like I'm under surveillance whenever I attend anything," laments Royster. "I think we all just want to be seen in a mainstream world we want to be seen within."

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Author Francesca Royster on Black country music fandom in the modern era

Solve the daily Crossword