Author James Patterson talks ‘The Last Days of John Lennon’ book and what could have been: ‘I just think he had room to grow’

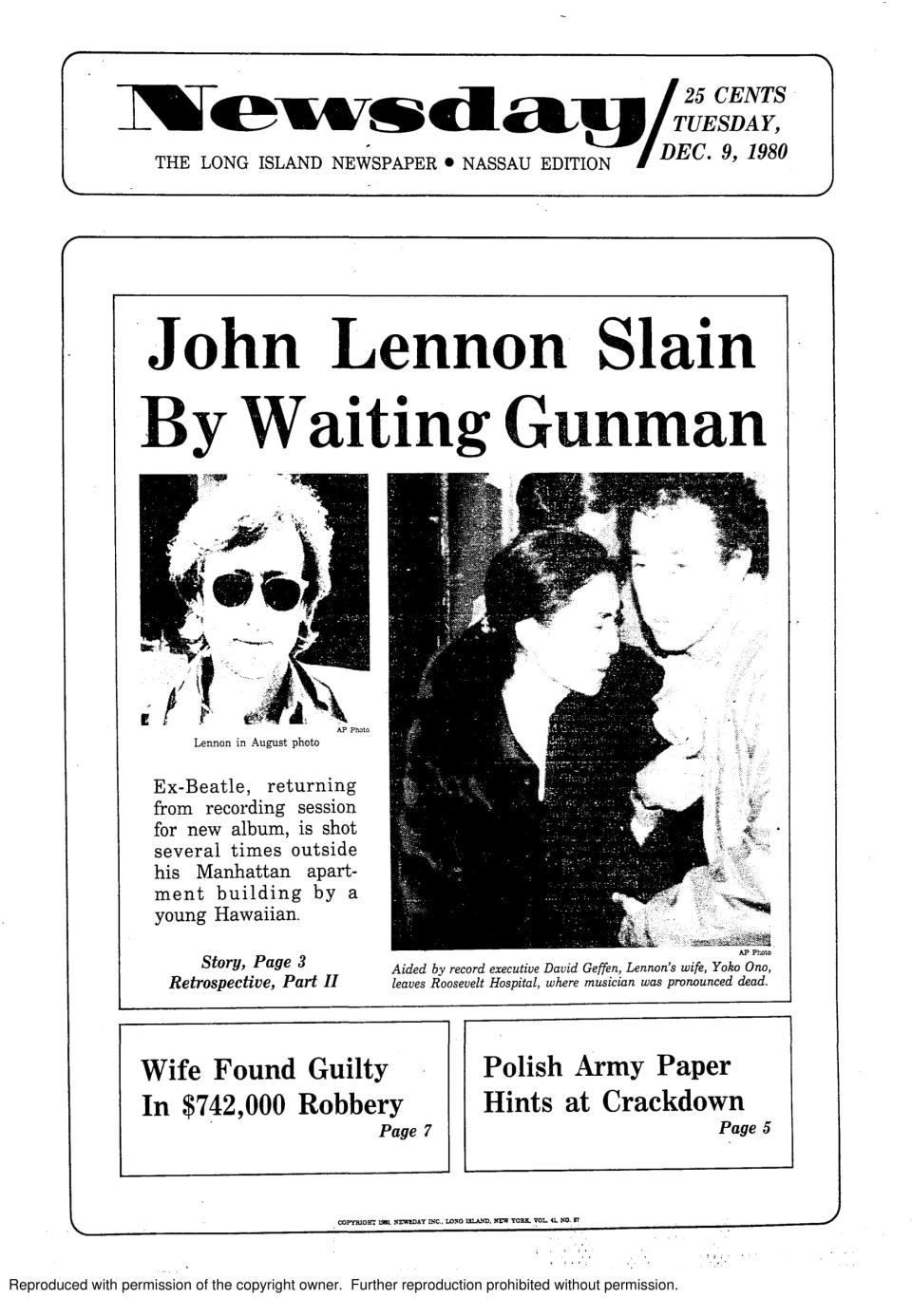

Forty years ago, on Dec. 8, 1980, John Lennon was shot dead in the archway of his Dakota apartment building by a “fan” named Mark David Chapman, who had traveled to New York City from Hawaii, with a .38 special revolver concealed in his luggage, specifically with this deadly mission in mind. One of rock ‘n’ roll’s greatest tragedies, the story of the former Beatle’s murder has been told many times. But it’s never been laid out quite as methodically as in the new book The Last Days of John Lennon, penned by best-selling author James Patterson (who lived in New York back in 1980 and actually rushed to the scene of the crime that horrible night) with the help of co-writer Casey Sherman and Dave Wedge.

In The Last Days of John Lennon, Patterson, known for his psychological-thriller novels like Kiss the Girls and Along Came a Spider and non-fiction true-crime works like The House of Kennedy and All-American Murder: The Rise and Fall of Aaron Hernandez, the Superstar Whose Life Ended on Murderers' Row, turns his investigative eye toward the events leading up Lennon’s tragic murder at age 40 — including chilling glimpses of the internal dialogue running through the mind of Lennon’s killer. But Patterson, ever the consummate storyteller, ultimately focuses much more on Lennon’s legacy as a musician, humanitarian, husband, and father than on Chapman, because, as he puts it, “As a character, [Chapman’s] not the most interesting. … He doesn't come off as a hero in [the book], I’ll tell you that.”

In the conversation with Yahoo Entertainment/SiriusXM Volume below, Patterson discusses how he uniquely – and carefully and respectfully — approached the saga of Lennon’s life and death, how Lennon’s assassination changed (or, sadly, didn’t change) opinions about gun control in America, what he learned from interviewing everyone from Paul McCartney to Geraldo Rivera during the course of his research, and what he thinks Lennon would be doing now if he were still alive.

Yahoo Entertainment: I understand you were actually at the scene the night of John Lennon’s murder.

James Patterson: Yeah, I lived on Central Park West. This is in 1980. I was nine blocks away from the Dakota, where John was killed. When I heard [the news], I went up there, and there were already a hundred people outside of the Dakota at that point, mostly playing songs on tape recorders — Beatles songs, Lennon songs — singing “Give Peace a Chance” and “Working Class Hero” and “love, love, love.” And then a few days later, that big [Dec. 14 candlelight vigil] in Central Park, I also went to. One of the weirder things, though, in terms of the Lennon connections, is at my [current] house in Florida, there’s a bridge that connects this house next door. John and Yoko owned that house and were refurbishing it when he was killed, and they were expecting to live there. … So, there's all these weird, spooky things.

Obviously there have been many books about the Beatles or Lennon, and a couple specifically about Mark David Chapman. As someone who’s written many psychological thrillers, how did you apply that true-crime approach to this story?

My notion was to write a book that would cover the murder a little like the way Versace was covered when they did [The Assassination of Gianni Versace] on Netflix. We would expose people to the Beatles’ story first. It's funny how people don't know as much as you think they know. … I mean, a lot of people, especially people under 40, they know the Beatles songs, but they don't necessarily know the story, which is pretty amazing. So there's that, and then the thing that I don't think has been dealt with much is John and Yoko. That love story at the time bothered a lot of people. They didn't think Yoko was the right choice. But they were really in love. They had a bad patch, but especially in the end, they were in love. It was kind of a beautiful love story, a very different kind of love story. And I think now we're a little more open to love stories like that than we once were. So in terms of the book, it's those three elements.

I'm very curious how you got into the mindset of Mark David Chapman, in the chapters that focus on him in the days leading up to Lennon’s murder. There are a lot of internal monologues, which obviously had to be imagined, but you must've based that on the research you did.

Well, Chapman wrote some things; things have been written about Chapman. But I wasn't as interested in Chapman. The first draft of the book had a lot of Chapman; I didn't like it, and I cut it way back. He’s an obsessive personality, and you’re definitely with him [in the book] when he arrives in New York and he takes a cab ride in — which has been documented — from the airport, and he says something to the cab driver to the effect of, “My name is Mark Chapman. Remember if you hear it.” He knew what he wanted to do.

Did you cut down the Chapman stuff because you didn’t, essentially, want to give him what he wanted, which was notoriety and fame? It’s always a slippery slope to writer about a killer without glorifying the person.

That's part of the reason. I don't think Chapman's going to care one way or the other, and I don't think [the book] makes him famous. I don't even want to think about getting it to his [current] brain. I'm not too concerned about it. He's going to stay in jail now. ... He doesn't come off as a hero in it, I’ll tell you that. But I'm aware of the issue, and it's a legit one.

I know you have written about JFK, in The House of Kennedy. There are definitely some JFK/Lennon connections. A lot of people have talked about how, when the Beatles first came over to the U.S., one of the reasons they were so successful was because the country was in mourning and needed something to get excited about again. Any many people look at Lennon's assassination as being as just as seismic a tragedy as JFK’s.

Not just JFK! I mean, for my generation, it was JFK, Bobby Kennedy, Martin Luther King, even to some extent Reagan. [America was] the assassination capital. Even when the band came over here, the Beatles were afraid for their lives because they'd had that controversy where John had said, ‘We're more popular than Jesus now.” And he wasn't bragging; he actually thought it was kind of outrageous and silly. But it didn't go over well, especially in parts of the South, and there were a lot of threats on their lives. We [Americans] do that. We threaten people's lives. It's bizarre.

The gun stuff is very chilling to me, throughout the book, going back to the JFK link — the fact that Lennon knew guns were rampant in America, and that the JFK assassination coincided with the Beatles’ beginning, and that Lennon always worried that he would get shot, that this would happen to him too. The famous, very disturbing image of John Lennon's round glasses, cracked with blood splatters on them, has been used a lot to promote gun control. Yoko Ono has actually used it on social media to protest gun violence and bring up the issue. How do think John Lennon's murder factors into the ongoing gun control debate?

Obviously it doesn't, unfortunately. It just doesn't. I don't get the gun thing. … I never even hear somebody say something that's kind of intelligent about it. You go, “Well, I want to understand, so tell me, explain to me, the gun thing.” I had a gun briefly, for about six months in New York City, and then I just went and turned it into the police station. I just didn't want to have it in the house. I wasn’t comfortable with it.

Yet it seems like Lennon wasn’t that paranoid once he actually took up permanent residence in New York City himself.

Yes, I spoke to Geraldo Rivera [for the book], and he had been spooked because he ran into John and Yoko at one point, and they were just wandering around in New York. John didn’t have a bodyguard! I think for some reason, John thought — which is not accurate — that he was a little more anonymous in New York, certainly more than he was in London. He felt safer in New York, and he did feel that he wouldn't be recognized quite as readily. And so he wandered around. I think it was his nature to think, “I'm just a working class hero. What's the big deal?”

Charles Manson is brought up in your book, obviously because of “Helter Skelter,” but we all know the story of how Manson may have had it in for Dennis Wilson or Terry Melcher, because he was a failed, frustrated musician and his recordings had been rejected. That made me think of a similar revelation in your book: that Chapman had sent a mocked-up album cover of himself to John and Yoko, which was found later in a pile of “fan” mail. Was Mark a frustrated wannabe rock star too?

I don't know about that, but the thing with Chapman is, there’s just this incredible upsetting way people are with obsessions. And he was obsessed. And the whole notion of that connection to Catcher in the Rye — at one point, he thought that John was in a sense kind of a catcher in the rye. And then he got disappointed in John. It was partly the religious thing. He didn't appreciate that [the Beatles] were “more important than Jesus.” But Chapman then somehow, in his head, thought he would be the one saving kids from going over the cliff. He would be the catcher in the rye. And one of the things about obsessed people, which is also interesting given the current political climate, is people who think differently from other people therefore think they're smarter than everybody else… not to fill in any names there, but, that's what Chapman was. Obviously he did feel that he thought differently, and so that was proof that he was a “genius.”

One thing that struck me while reading this book is that even though Chapman went to New York with a certain mission, which was to target Lennon, at some point he did consider maybe, if he couldn't get to Lennon, achieving his goal by murdering another celebrity instead. He almost did that at this random party with Leslie Nielsen and Robert Goulet that he wandered into….

He had a couple [public figures] that he had his eyes on. He had his eyes on Nixon for some reason, maybe a good reason. … I mean, there were a couple of interesting things that happened. He ran into James Taylor [in a subway station] during those two days in New York. And interestingly, I'm sort of a big rock ‘n’ roll guy, believe it or not. Like, I was an usher at the Fillmore East, and then I worked at the McLean [psychiatric] hospital outside of Belmont. And James Taylor was a patient there. So I knew James a bit, when he was in the hospital. He wasn't famous yet, but he had written several of the songs – “Fire and Rain,” “Sweet Baby James,” et cetera — and he would go in the coffee shop in the hospital and play the songs. I would sit like 10 feet away, and there's James Taylor. So that's another little hook into this thing.

Well, maybe Chapman once considered going after another celebrity, but it seems he had a real personal hatred, a vendetta, against Lennon — almost like he felt he had been betrayed personally by Lennon. Where did that come from? Was it mainly that “bigger than Jesus” comment?

I think that was a piece of it. I think the way Lennon was acting… I'm not exactly sure what [Chapman] wanted [Lennon] to be, but what Lennon was when he was just a “rock star,” a Beatle, that somehow worked for Chapman. And then as Lennon evolved, that wasn't working [for Chapman] at all. I'm sure the Yoko thing didn't work for him either. Obviously with John and Yoko, they were doing a lot of things that people were scratching their heads about — the photography, the music they were making. A lot of people just felt like you're not allowed to change, for some reason.

As you said, you were particularly interested in writing about John and Yoko’s relationship. And you mention that the public perception of Yoko has improved over the years, become kinder. What are your thoughts on how she was just so vilified at the time?

It's awful. I think it's unfortunate. But they were so different. And I think that's one of the reasons that they fit together. They both had a very unusual, poetic, artistic view of the world in their lives, and they wanted to live that way. And a lot of people couldn't accept the art that they created together. I mean, the night John was shot, they were just returning from working on one of Yoko's tracks in the studio.

Yes, “Walking on Thin Ice.” Your book says that the producer, Jack Douglas at the Hit Factory, wiped clean those session tapes dated Dec. 8, because John was acting strangely that night. Any insight into why Jack did that?

I don't know the answer to that, but I mean, it'd be kind of cool if he didn't want that to be the last musical thing about John Lennon.

Where do you think Lennon would be, musically or personally, if he hadn’t died in 1980? He was only 40 years old, and he was having this big resurgence commercially and creatively—

And humanly, as a man and as a father! … I think that one of the tragedies here is that at age 40, John was a good father, a much better father than he had been earlier in his life. I think — and Yoko has said this as well — that he was a much better husband. He was a good husband, a loving husband. And he had just done his first album, Double Fantasy, in five years. I don't know what the right word is, but I think he was rediscovering himself as an artist, which is hard when you've had that kind of fame. I mean, what do you do? You're “Jesus.” And you come back from the dead at 38: “What's my next act?”

In terms of today’s politics, what do you think John would make of all the craziness that’s going on right now?

John was the one who somehow wanted to take what people were doing and make a bigger dent in terms of the world — you know, do something to help with the Vietnam War, get people's heads turned around a little differently. … I think he always wanted to combine that [with music], and it rubbed off in society in a good way. So I think he would have kept trying to do things like that. He wasn't highly educated. I think he became more of a reader. I think he was more of a thinker. I just think he had room to grow.

I know you interviewed a lot of big names for this book, like Elton John and Billy Joel, but most fascinatingly, you also spoke with Paul McCartney. What insight did you get from him?

That was interesting, because all through their seven years — and that's all it was, seven years, the Beatles, a couple of hundred songs, which is amazing — they both wanted to be the leader of the band. They both wanted to be Billy Shears. So, there was always some competitiveness between the two of them. And then after the breakup, it got nasty for a while; they would write about each other in their songs. And so it was very unpleasant toward the closure to John's death. They started communicating more, and I think Paul was concerned about John for a while. And I think at this stage, Paul just misses his friend. He regrets what happened. He wishes they could have patched it up.

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment:

· Julian Lennon's afterlife Earth Day message from father gave him 'goosebumps for days'

· John Lennon: rocker's troubled muse, 40 years on

· Sir Paul McCartney looks back 'like a fan' on first time he met John Lennon

The above interview is taken from James Patterson’s appearance on the SiriusXM show “Volume West.” Full audio of that conversation is available on the SiriusXM app.

Follow Lyndsey on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Amazon, Spotify.