“When you’re the bass player and it’s time for the solo, you go nuts, because you’ve been playing rhythm for everyone else for so long!” Tony Visconti on David Bowie’s The Man Who Sold The World

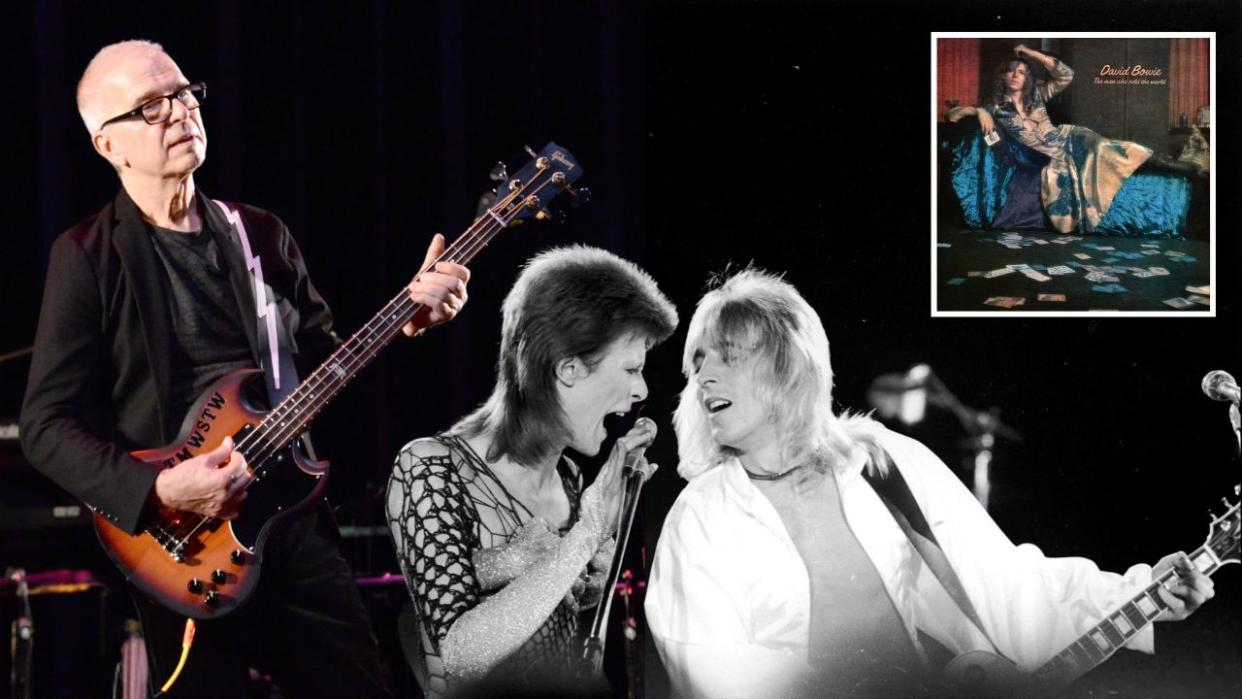

In September 2014, fans of a certain glittering era in British rock music were treated to four unique concerts in which David Bowie's 1970 album The Man Who Sold The World was performed in its entirety. The album's producer and bassist, Tony Visconti, was there, as was original drummer Woody Woodmansey, while vocals came from Heaven 17 singer Glenn Gregory and guitar was supplied by Steve Norman of Spandau Ballet in the absence of the late Mick Ronson. Bowie himself didn't take part, but gave the dates his blessing.

Visconti, who we spoke to just before the shows, had a long and creative relationship with Bowie that extended to the great man’s final studio album, Blackstar, which was released in January 2016, just two days before his death.

Asked about his extravagant bass playing on The Man Who Sold The World, Visconti told BP: “I can still play like that now, but there's not much call for it. When I started out playing bass I was a jazz bassist on the double bass – so I was playing far-out solos when I was 16 or 17. When you're the bass player and it's time for the solo, you go nuts, because you've been playing rhythm for everyone else for so long, but the person who really spurred me an was Mick Ronson.”

“David and l adored Mick and looked to him for advice and guidance, and Mick said I had to listen to Jack Bruce playing with Cream. That was the style he wanted me to play. Jack's style was lead bass, which was similar to mine. I was also influenced by Noel Redding, who was a friend of mine: I adored the Jimi Hendrix Experience and saw them live several times. So this style of playing was in the air at the time, and I loved it!”

Visconti's memories of recording the album remained clear. “I was working hand in hand with the engineers to get a sonic identification for the band. We worked as an arranging team: I wasn't exclusively calling all the shots just because I was the producer. The song Black Country Rock has my bassline, and Width Of A Circle has David's melody, and the opening riff is his. We had such a ball making that album, because we were a real band, and the tragedy is that we never got to perform it live.”

So what happened, we ask? “We had every intention of going out on the road as David Bowie & The Hype. It never happened because David had his hit, Space Oddity, and he met Tony DeFries, who he adored and wanted to manage him because he was parting ways with his previous manager, Ken Pitt. It was a changing of the guard, and I had some business with Tony DeFries of my own, before David even met him, because he worked for the accountancy firm that I used. I didn't trust Tony, and David and I fell out over him.

“Plus Tony didn't like the idea of the band: he told David, ‘You don't need these guys.’ Mick and Woody went back to Hull for a whole year before they made Hunky Dory together, and then went on to do Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars. So Tony DeFries was the catalyst that foiled all our plans, really!”

It's all ancient history now, of course, and the zest with which Visconti and drummer Woodmansey attacked the old material spoke volumes about the quality of the music. Listen to pretty much any song on the record and you'll encounter some fairly complex bass parts; how did Visconti address them when he came to rehearse again after all these years?

“I started practising on my Fender P-Bass, because I played that bass on a few songs on the album. But when I came to do Black Country Rock, I didn't remember the main bassline being that hard to play. You have to stretch from the E to the G# on the A string. I realised that I'd played a Gibson EB-3 on that track, so I went and bought myself a new Gibson SG bass. The SG has about the same scale as the EB-3, like a 30.25-inch scale, so all of a sudden I found myself playing notes that I couldn't play on the P-Bass.

“That was the Jack Bruce style of playing, on a little bass, with real fast runs. There's a triplet run when it goes to the D boogie section on Width Of A Circle, and I'm playing a very fast G triad. It's GBD, then F#DA, very high on the neck – and that would be impossible on a P-Bass with my size hands. I don't have big hands. I could play it on the SG though!”

Like the petty hacks we are, we spotted a bum note and felt the need to tell Visconti about it. It's at 06:58 on Width Of A Circle. When this is pointed out, rather than telling us to get stuffed as we deserved, Visconti merely laughed and said, “Oh, towards the end? That's an old musician's trick. If you make a mistake, do it twice and it sounds like you did it on purpose. I think I played a D when it was an F, but you could play a D against an F chord, certainly in jazz.”

Visconti's bass tone is to die for on the album – fat, overdriven and falling off the rails especially towards the end of She Shook Me Cold. How did he achieve it in the days when effects for bass were almost unknown? “I had a very powerful valve bass amp, a 200 watt WEM, with two 2x15 cabinets. I did what Mick did and just turned everything up to 10: those speaker cabinet were vibrating heavily and dancing round the studio! I only had one effect in those days and that was a Fuzz Face, so possibly I put it in there for a little overdrive, but it wasn't turned up much, because a lot of the distortion was coming from the amp.”