The Beach Boys Look Back on Their Story of Survival in New Doc (Exclusive)

Six decades into their reign as America's Band, the iconic group reflect on riding the waves of rock 'n' roll chaos and crafting their timeless pop masterpieces.

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty

For those who were around for the early days of rock & roll, the first image they probably saw of the Beach Boys was on the cover of their 1962 debut album Surfin’ Safari. Clutching a surfboard on the sands of Malibu’s Paradise Cove, their eager teenage faces gleefully survey the horizon and a future they could scarcely imagine.

Last September, over 60 years later, the surviving members reunited at the very same spot to raise a toast to their remarkable legacy. The scene is the centerpiece of the new Disney+ documentary The Beach Boys. Directed by Frank Marshall and Thom Zimny, the film details how family ties kept the band together throughout tumultuous ups and downs as they penned a new chapter in Americana with their canon of ‘60s classics. Mike Love served as the longtime lyrical laureate, igniting fantasies of a beach utopia for generations of landlocked listeners across the globe, while his cousin Brian Wilson evolved into a Mozart for the transistor radio era, crafting symphonic pop that goes down easy thanks to honey-soaked harmonies.

“It really brought me back to those days with the boys, the fun and the music,” Wilson tells PEOPLE of the documentary. The 81-year-old rock icon attended the LA premiere at TCL’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood on May 21st, flanked by his children and bandmates. The occasion marked his first public appearance since a judge granted a conservatorship due to an unspecified neurocognitive disorder. Despite his health struggles, and the death of his wife Melinda Ledbetter at age 77 in January, those close to Brian say he’s staying healthy with physical therapy — and he’s still singing.

Alberto E. Rodriguez/Getty Images

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA - MAY 21: (L-R) Al Jardine, David Marks, Frank Marshall, Brian Wilson, Blondie Chaplin, Mike Love and Bruce Johnston attend the world premiere of Disney+ documentary "The Beach Boys" at the TLC Chinese Theatre in Hollywood, California on May 21, 2024. (Photo by Alberto E. Rodriguez/Getty Images for Disney)It’s been a time of reflection for the group, who published a new oral history book in April. Culled from new interviews and archival material — including hundreds of never-before-seen photos, the 400-page tome is the first time the Beach Boys have told their own story in print. The surviving members recently spoke to PEOPLE about their unlikely story of survival and how they’ve managed to keep summer alive for six decades.

FAMILY HARMONY

The Beach Boys were born in the back of the Wilson family car as young brothers Brian, Dennis and Carl sang to pass the time on drives through their hometown of Hawthorne, California in the early ‘50s. During holidays they showcased their talents at regular get-togethers held at the upscale home of their cousin Mike Love. “We had a big, beautiful living room with a grand piano and a harp,” he tells PEOPLE. “We had all our parties there: birthdays, Thanksgiving, Christmas, New Years — you name it. We would get together and harmonize and sing. Music was it for us. It was a family hobby.”

Love and Brian bonded over a shared love of doo-wop and harmony groups like the Everly Brothers, Frankie Lymon & the Teenagers, and the Olympics. This passion quickly blossomed into an obsession for Brian, whose childhood fascination with the majestic sweep of George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” was now rivaled by a jazzy singing quartet called The Four Freshmen. He sat at the family piano for hours painstakingly dissecting their complex vocal arrangements by ear before enlisting his parents — and his reluctant kid brothers — in elaborate singalongs.

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty

Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys gather around the piano, 1964His efforts helped bring harmony to an unhappy home. Wilson patriarch Murry was a strict disciplinarian prone to angry outbursts and punishments that frequently veered towards the sadistic. “At times he was extremely frightening,” Carl Wilson recalls in an archival interview included in the documentary. (Both Dennis Wilson and Brian would accuse Murry of physical abuse on numerous occasions throughout the years.) An aspiring songwriter with a modest hit to his name, the quickest way to Murry’s heart was through music, and these gatherings around the piano were cherished moments of peace in the otherwise tense household.

In addition to his brothers and cousin, Brian soon recruited Al Jardine, a friend he met on the high school football team. Their early encounter on the grid-iron wasn’t exactly auspicious as Brian (the QB) made a sloppy throw that resulted in a broken leg for Jardine. “So we never say ‘Break a leg!’ to each other!” Jardine laughs. His career as a halfback was over, but his musical journey was just beginning. “Brian and I reconnected later and started singing around the campus piano at El Camino College. Then he introduced me to his brothers. We clicked immediately. We had a band and a new family: the Beach Boy family.”

CALIFORNIA DREAMS

A crucial catalyst for the young group came one weekend in 1961 when the Wilson parents took a vacation to Mexico. Using money left behind for emergencies, the teenagers rented instruments to record early compositions by Brian and Love. “We were desperate to begin to play our stuff,” recalled Jardine, who persuaded his mother Virginia to chip in a whopping $300 after a brief audition. (It helped that they sang an a capella version of “Their Hearts Were Full of Spring,” an old standard guaranteed to bring a tear to the eye of any parent.)

One of the tracks they recorded was inspired by a new coastal fad suggested by brother Dennis: ”Surfin’.” It would earn them their first record deal and provide the group with an identity — though none but Dennis surfed with any regularity. “I was into cutting class and sneaking off to the beach,” he says in an archival clip included in the documentary. “I love the ocean.” Brian, meanwhile, wiped out during his one and only attempt and was nearly struck in the head by his board. Jardine had a similarly disastrous experience. “I almost drowned,” he admits in the film. “We were landlubbers.”

Other songs were more true to their own experiences as teens. “It was just a phenomenal time growing up in Southern California,” recalled Love, who penned the lyrics to many of these formative tunes. “The beach was important and our cars were important. You had the El in Chicago, or the subways in New York, but California didn't have that. Southern California had freeways. Our environment gave rise to the subject matter that we put in our songs: surf and cars.”

Love’s lyrics for 1964’s “Fun Fun Fun” were set at the local Fosters Freeze hamburger stand where they often hung out. “That song has an energy to it,” he says. “Every kid that gets their learners permit wants to borrow the car, right? It's just so classic. They want to hang out to see and be seen, you know? It’s classic Americana, you know?”

The familiar subject matter helped the songs instantly connect with their peers, and within a year of recording their first demos, the young band (Love the oldest at 21, and Carl Wilson only 15) left school and set out on tours of Southern California. The Wilson brothers’ father Murry acted as manager and sheriff, keeping his teenage charges in line with a much-loathed fine system — docking their pay for swearing, missing bed check, or showing up late for rehearsal.

“We would get in our station wagon with a U-Haul trailer and go a couple hundred miles up to Bakersfield and play on the top of a radio station in hundred-degree weather,” remembers Love. “Our tennies were sticking to the asphalt on the roof! It was just real hardcore work.” But the pay-offs were obvious and immediate. “I can remember the first time we heard girls scream,” Dennis recalls in the documentary. “We thought there was a fire! It was fun.”

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty

It wasn’t long before the Beach Boys graduated from a local act to national stars. Their run of early hits sold a fantasy vision of California to the rest of America through Love’s lusty and exuberant poetry and Brian’s lush and inventive music. “The way it started out was real fast, we didn’t have a chance to sit around and think, ‘Hey, what happened?’” Brian observes in the documentary. “We were already heading towards something without really knowing it.”

RIDING THE WAVE

Brian blossomed in his role as the Beach Boys’ chief musical creator. At a time when even the Beatles and Bob Dylan — his nearest peers and friendly rivals — relied on studio professionals to translate their musical visions, Wilson pioneered the multi-hyphenate role of writer-performer-producer essentially by himself. In the space of two years he crafted an astonishing five albums packed with 10 Top 40 hits. Even his bandmates were in awe of his almost supernatural ability to hear full arrangements in his head. “Brian always knew what he wanted and would assign certain parts,” Jardine explains. “When you're in the presence of genius, it's pretty heavy.”

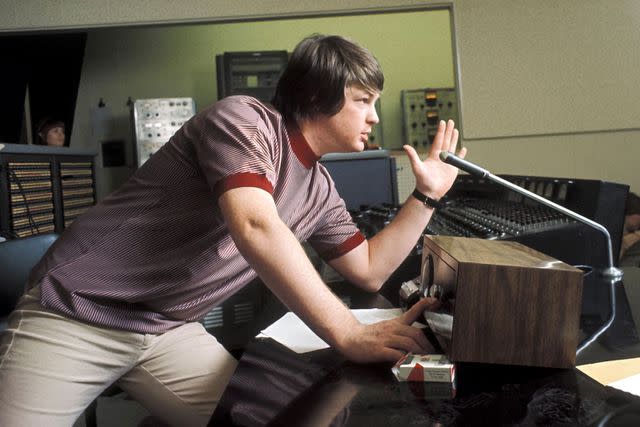

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

LOS ANGELES - 1966: Singer and mastermind Brian Wilson of the rock and roll band "The Beach Boys" directs from the control room while recording the album "Pet Sounds" in 1966 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)Love believes the interlocking vocal blend was the key to the band’s success. “That's the thing that distinguished the Beach Boys from so many other groups: those sophisticated four-part harmonies were in the background of all these rock themes.”

By 1964, the strain of the workload began to take its toll on Brian. After suffering a panic attack during a flight while on tour that December, he retired from the road to focus on developing his skills as a composer and arranger with increasingly daring studio productions. The evolution was clear mere months later with the release of “California Girls,” with its glorious orchestral prelude — a musical manifestation of the first rays of a summer sunrise — evoking works of classical composers like Aaron Copland and Brian’s boyhood hero, George Gershwin.

But his ambitions kicked into overdrive after hearing the Beatles new album Rubber Soul in December 1965. Stunned by its sonic and thematic unity, it inspired him to expand his canvas from three-minute pop singles to a full album. “I wanted to grow musically,” he told PEOPLE in 2018. “I thought we’d do something experimental and with a lot of love. We had worked together for a long time and we were ready.”

The result was Pet Sounds, a stunning work of musical mastery and lyrical maturity, frequently ranked as one of the greatest albums of all time. “I'd say Brian was one step below God,” says Bruce Johnston, the self proclaimed “new guy” who joined the Beach Boys in 1965 as a touring replacement for Wilson and quickly became an integral full-time member of the band. “He’s pure music. I'll never meet anyone again like Brian. His harmonies are beyond perfection.”

Johnson took copies of the album to England soon after its release in the spring of 1966, where he played it to the Beach Boys’ friendly rivals: the Beatles. “Lennon and McCartney showed up in a Rolls-Royce with their Edwardian suits on,” he says. “They listened to the album twice and just totally flipped out. They were raving like crazy about it.” In the immediate aftermath, McCartney went home and wrote the ballad “Here, There and Everywhere” for the album the Beatles were recording at the time, Revolver. “Paul distilled the harmonies and the sweetness from Pet Sounds into that,” says Johnston. (McCartney would later credit the album as an inspiration for the Beatles’ groundbreaking Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart Club Band, and cite “God Only Knows” as one of his all-time favorite songs.)

The Beach Boys topped Pet Sounds commercially and creatively that autumn with “Good Vibrations.” Their most adventurous work to date took 90 hours of sessions stretched over six months to complete, making it the most expensive single ever made at the time. Brian employed the innovative approach of stitching together short musical fragments — sometimes recorded weeks apart, often in different studios — the way a filmmaker would edit a film. The finished product was a modular pop symphony unlike anything that had ever been heard before.

“That was the top,” admits Love, who wrote the lyrics to “Good Vibrations” on his drive to the studio following a last-minute request from Brian. “It’s a true collaboration with my cousin.” Despite the tight turnaround, the words crystalized both the spirit of the age and the ethos of the band. “It was all about peace, love and harmony,” he says. “Good Vibrations” was the Beach Boys’ next No. 1 — and their last for 22 years.

TRANSITION AND BETRAYAL

Brian grew increasingly overwhelmed by the mental health challenges that would side-line him for much of the next few decades. “It’s a struggle like any struggle,” he says in the Beach Boys oral history book. “It’s something I’ve had to carry around most of my life and something that really kept me off balance until I learned how to get my head around it.” His follow-up to Pet Sounds, the hugely ambitious “teenage symphony to God” known as SMiLE, would be abandoned for the next 37 years, attaining mythic status as one of the great unfinished masterpieces in modern history.

The creative setback rocked Brian’s fragile confidence, and by the early ‘70s, the man who’d written “In My Room” had largely confined himself to bed while his band soldiered on in his home studio downstairs. “Brian was a recluse for a while,” says Love. “Other people came forward with more songs. It became more of a democratic process.” Despite a string of strong albums, the band’s fortunes continued to flounder as their fun-in-the-sun reputation rendered them passé in an era when psychedelia, protest anthems and hard rock ruled the airwaves. “The band was being considered — so wrongly! — as surfing Doris Days,” says Johnston. Their 1970 album Sunflower, a skillful group effort regarded today as one of the strongest works of their career, only reached #151 on Billboard. It was a long fall from the top of the charts.

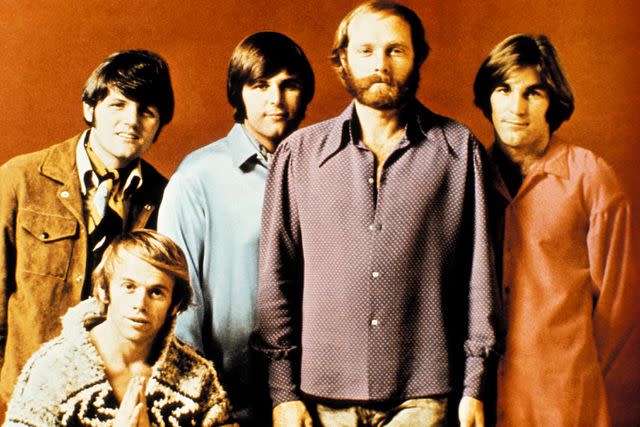

RB/Redferns

The Beach Boys circa 1969Wilson patriarch Murry believed the Beach Boys’ moment was up. His heavy-handed management style led to Brian firing him as the band’s manager at the peak of their career in 1964 — causing a rift between father and his three sons that would never be fully healed. Despite his dismissal, Murry’s paternal status meant that they could never fully be rid of him, and he remained an uneasy presence in their lives.

The documentary features audio of Murry, worse for the wear after a few drinks, crashing the recording session for the future No. 1 smash “Help Me Rhonda.” After his unsolicited critiques of their vocal phrasing are not well received (“Brian, I’m a genius too.”) he begins hectoring his eldest boy, telling him he’s going “downhill” in front of the band and assembled studio staff, and reminding him of their family motto: “Fight for success.” Though Murry would deny physically abusing his sons, the audio is a troubling peek into their family dynamic.

Even after his ouster as the band’s manager, Murry continued to control the band’s publishing. Without consulting his sons or his nephew, he sold their catalog of hits in 1969 for $700,000— roughly $6 million when adjusted for inflation. Today, Bloomberg reports its value at upwards of $100 million. The move became the source of several inter-family legal squabbles, notably when Love discovered that his uncle left him uncredited on dozens of hits he’d co-written. “Mike never was paid or got credited for writing songs like ‘California Girls’ — not so good,” Johnston says. The only way to remedy the situation was for Love to take the heartbreaking step of filing a lawsuit against his cousin Brian. (In 1994, a U.S. District Court awarded him credits on 35 Beach Boys classics — including hits like “I Get Around,” “All Summer Long,” “Dance, Dance, Dance,” “Help Me Rhonda” and “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” — and $13 million in unpaid royalties.) “Even though it's fixed, it's not really fixed,” Johnston continues. “It was his uncle! The dishonesty of it was just insane.”

Johnston speculates that the root of the ugly incident is a family feud that long predates the band. “The Loves were the prosperous side of the family, because they had a very successful sheet metal business. Back in the day, Mike's dad used to buy a new Cadillac every year and they had a big house. Maybe he [Murry] resented them.” Regardless, the real reason for the betrayal will never be known. Murry died of a heart attack in 1973 at age 55, before making peace with his family, or seeing the band’s legacy flourish.

DEATH OF A BEACH BOY

Murry sadly wasn’t the only member of the Beach Boys family to die young. “Mortality affected us and drugs affected us,” says Love. “My cousin Dennis died in 1983. He couldn't get off the alcohol and the drugs.” From the outset, the drummer was the soul of the Beach Boys. “Dennis was an animal,” Jardine adds. “He was a good guy, and talented. He was the surfer in the band. That's how we came up with the idea to do a song about surfing in the first place. He was the one out there doing what we were singing about.” Enthusiastic about cars, girls and the beach, he embodied the free-spirited nature of the ‘60s — and the risks that it entailed.

One day in 1968 he brought a pair of female hitchhikers back to his Hollywood home. After leaving for a recording session, he returned to discover that they’d moved in with the rest of their hippie commune, headed by a self-styled guru named Charles Manson. The collective lived with Dennis for several months, costing him upwards of $100,000. Manson attempted to pay Dennis back by giving him a song, which the Beach Boys recorded for their 1969 album 20/20 under the title “Never Learn Not to Love.”

“Dennis got kidnapped, basically, by Manson and the Family,” claims Johnston. Ultimately Dennis abandoned his own home to put some distance between himself and the group, who would go on their murderous rampage mere months later.

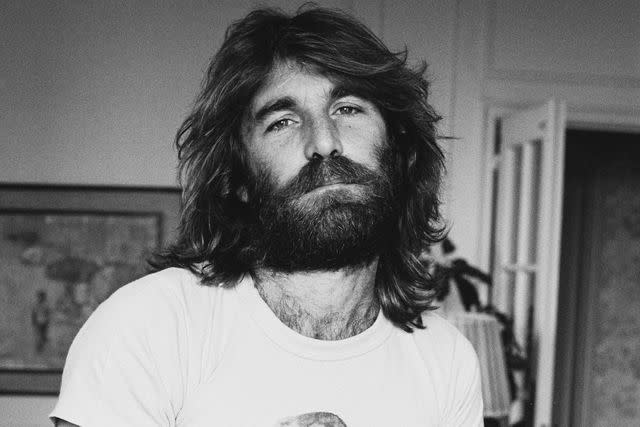

Michael Putland/Getty

Dennis Wilson in New York on September 6, 1977.The harrowing experience contributed to his worsening substance abuse problem that would undermine his promising future as a songwriter. He’d been drinking when, three days after Christmas in 1983, he drowned while diving at the Marina del Rey pier where his yacht was formerly docked. He was 39 years old. Fittingly for the only Beach Boy who surfed, he was buried at sea following special dispensation from President Ronald Reagan.

AMERICA’S BAND

The former California governor had grown close to his home state’s favorite sons and frequently invited the Beach Boys to perform Fourth of July concerts on the National Mall throughout the ‘80s. The semi-regular gigs attracted hundreds of thousands and cemented their status as America’s Band. “The D C. concerts were quite amazing,” say Jardine. “Huge, huge deal. We were at our pinnacle with respect to crowd appreciation."

The multi-platinum success of 1974’s Endless Summer compilation introduced the band to a new generation of fans, and 1988’s “Kokomo” made them unlikely chart-toppers more than 25 years after their first hit. The boost in popularity made them one of the hottest live acts on the planet. Johnston marvels at the multiple generations of fans he sees at the sold-out shows they continue to play across the country. “The Beach Boys are a kind of a musical Disneyland,” he says.

While on tour recently, Mike heard one of the band’s songs on the radio. Listening to his younger self harmonizing with his old friends and cousins — including Carl Wilson, who died of cancer in 1998 — evoked a sense of wonder. To him, “it sounded like angels.”

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.