'Beauty and the Beast' Lyricist Howard Ashman's Loved Ones Recall How He Brought Story to Life — and Changed Disney Films Forever

Beauty and the Beast is about an enchanted world where spells transform ordinary objects, characters burst into song, and hope blooms even in the darkest shadows. This was the vision of Howard Ashman, the lyricist and executive producer of Disney’s 1991 animated film: a man who, in the words of his sister Sarah Ashman Gillespie, “saw the world as a musical.” Tragically, Ashman died of AIDS after completing work on Beauty and the Beast and never saw the finished film. But his work has lived on, remaining essential to both the long-running Broadway stage adaptation, and now director Bill Condon’s blockbuster live-action remake.

“He really was the heart and soul of that original film, he brought it its wit and also its depth of emotion,” Condon said of Ashman, speaking to Yahoo Movies at the 2017 film’s press junket. “I think he’s in every frame of this new movie too.”

Moreover, Ashman’s approach to Beauty and the Beast’s music and characters created a template for every Disney fairy-tale musical to come. With the Beauty and the Beast remake entering its second week in theaters (and having earned more than $200 million in the U.S. in just five days), Yahoo Movies spoke to some of the people who were closest to Ashman, including his sister (who created the Howard Ashman website) and his former partner Bill Lauch, about Ashman’s contributions to the original Beauty and the Beast and the Disney legacy.

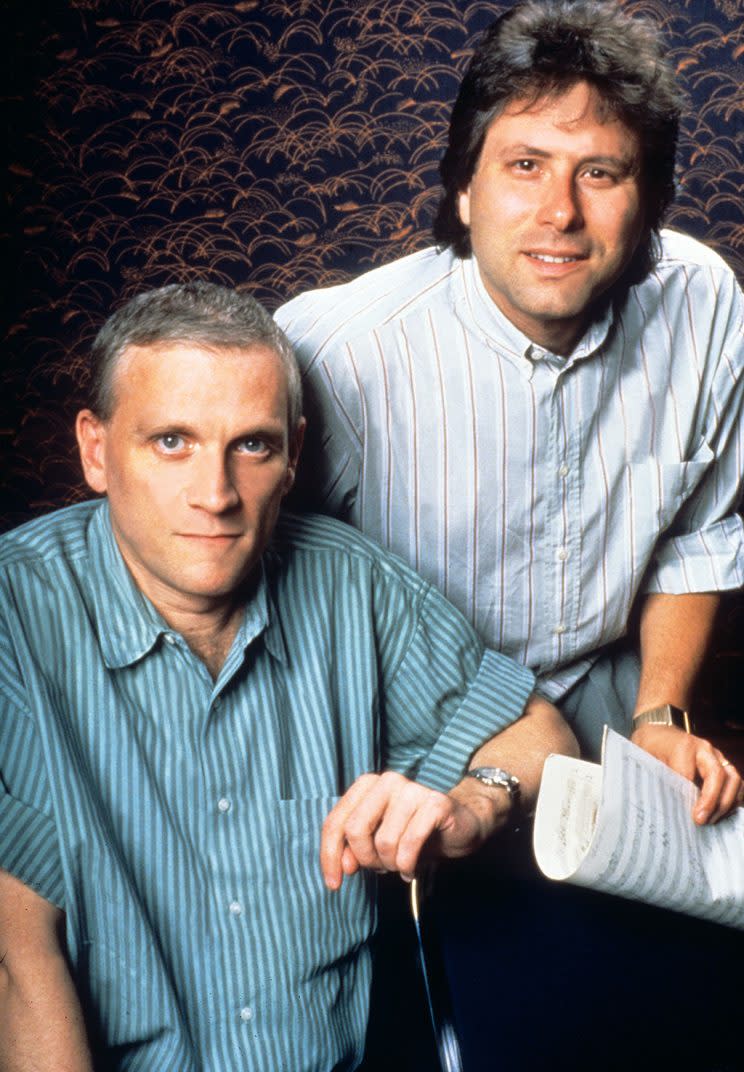

When Disney first approached Ashman, CEO Jeffrey Katzenberg was looking for ways to revitalize Disney’s signature animated unit (whose films had experienced a decline in quality and profitability after Walt Disney’s death in 1966). Ashman hit Katzenberg’s radar via Little Shop of Horrors, the hit off-Broadway show he wrote with composer Alan Menken (and which he later adapted into the 1986 film musical directed by Frank Oz). Ashman next wrote and directed the 1986 beauty-pageant musical Smile, which flopped on Broadway — and gave Katzenberg a chance to swoop in. “Howard was devastated, but Jeffrey came immediately to him and said, ‘We think you’re great, come out here and do what you want with us,’” says Gillespie.

After writing a song for the animated film Oliver and Company, Ashman (along with his Little Shop of Horrors collaborator Menken) was hired to write the score for The Little Mermaid, Disney’s first fairy tale adaptation in decades. Because of his theater background, Ashman consciously approached the film like a stage musical, teaching the Disney team about “I want” songs (of which Ariel’s “Part of Your World” became a classic example) and other Broadway storytelling tropes. “Because the studio was struggling, I think that they were very open to a new idea… and a new way to move forward in their animation,” Gillespie observes. “And so that was a beautiful opening for Howard.” Ashman also delighted in his job as lyricist. Gillespie remembers him asking his assistant to make a list of “every fish name” when he was writing Under the Sea, the song for which he and Menken were awarded an Oscar in 1990.

Watch Howard Ashman explain ‘I want’ songs in a clip from the documentary ‘Waking Sleeping Beauty’:

The Little Mermaid was an enormous hit, bringing Disney’s animated films back into cultural relevance and kicking off what is now known as the “Disney Renaissance” period. Thanks to that success, Ashman and Menken were given a crack at another animated film: Beauty and the Beast, a project that had already seen a few false starts at Disney. It was Ashman’s vision that songs should drive the story more fully than in any previous Disney film. “They were doing a Broadway musical as a movie,” says Gillespie. With that in mind, Ashman wanted to start the film with a big opening number, an idea that had been shot down when he and Menken pitched it for The Little Mermaid.

“He and Alan actually wrote a demo of a much longer opening for Mermaid and the execs were apprehensive,” says Lauch. “It was like, ‘This is a kid’s movie and attention might be lost right at the beginning if you give them something they’re not familiar with.’ It was out of the box for them.”

For Beauty and the Beast, he and Menken were determined to write an opening number that Disney would approve. The result is “Belle,” a seven-minute musical sequence (watch it below) that brings the audience directly into the heroine’s world. “They worked very hard on that song,” says Lauch. “And when you look at it analytically, you see that it incorporates many things: you get information about characters, and it gives you a tour of the town, and except for the beast, it pretty much introduces all the central characters that you’re going to follow through the film. And so it was very well crafted. But yeah, it was a bit of a sell!”

The opening song was just one of the crucial ways that Ashman shaped Beauty and the Beast’s story and characters. The enchanted household objects were always part of the film’s concept, as Gillespie remembers it, but it was Ashman’s idea to turn them into fully developed characters. He also came up with the notion that they were servants transformed by the Beast’s spell — a decision that, as Gillespie puts it, “gave them more skin in the game.”

Ashman also had a major role in developing the film’s brainy, spirited protagonist, along with screenwriter Linda Woolverton. “Howard and I really conjured up Belle,” Woolverton told Yahoo Movies’ Kevin Polowy in an interview last year. “We were just trying to create a new Disney heroine that was representative of her age and certainly relevant to the time. We just didn’t want her to feel like a throwback.” Gillespie recalls the pride that Ashman took in Belle being “a different kind of heroine — I think he very much liked her being bookish and feisty, which actually Ariel is as well. Howard liked feisty heroines.”

One of Ashman’s major story contributions is something that most of the audience has probably never thought twice about. “You would assume it is the story of Belle, but I think the thing that Howard recognized is that it’s actually the Beast’s story, and the story of redemption, and how a person who makes a mistake and is a bad person can be rescued,” says Lauch. “And I think that’s what kind of gave the film heart and depth, that you witness his transformation. And it happens on both sides of that romance also — she’s horrified, but then comes to see the inner beauty in the beast. But that’s something that Howard thought was important, and I think changed how they wrote the film.”

Along with his strong sense of story and his gift for crafting unforgettable lyrics, Ashman had a knack for helping actors develop their characters. On Beauty and the Beast, he worked with Angela Lansbury, who was surprisingly nervous about her ability to sing the role of Mrs. Potts. “I think she was happy to do the voice, and really liked the role, but was very apprehensive about singing the title song,” Lauch recalls. Several years removed at that point from her musical theater career, Lansbury worried that she wouldn’t do justice to the film’s central song. “And so Howard convinced her that she was capable of this by singing the song for her,” says Lauch. “And Howard was a great mimic. He didn’t do this in a way that he was impersonating Angela Lansbury, but he did it in the character of Mrs. Potts. They had a private session together and she came out of it with the confidence that she would be able to handle this song. “

Sadly, while Ashman was putting his heart and soul into Beauty and the Beast, his body was starting to fail him. The AIDS crisis in the United States was approaching its peak, and gay men like Ashman were disproportionately affected. As Menken said in an interview for the Howard Ashman website, “The period from 1981 thru 1995 was like living through a war, with unthinkable casualties and no end in sight.” In the early 1980s, Ashman had written a song, “Sheridan Square,” about all the friends he had already lost to AIDS. His own diagnosis came during production on The Little Mermaid. Because of the shame and fear that still surrounded the epidemic (which the Reagan administration had almost entirely refused to acknowledge, even as thousands were dying), Ashman kept his HIV status a secret from all but the people closest to him until shortly before his death.

By the time Ashman was hired to write Beauty and the Beast, his health had deteriorated to the point where he didn’t feel comfortable traveling back and forth from New York to Los Angeles. Katzenberg (whom Ashman had told about his diagnosis, along with Menken) arranged to have the production team stay for several weeks at a hotel in Fishkill, New York, close to Howard and Bill’s home, while they developed the story. After the film was completed, Ashman was able to see a work-in-progress screening, but he didn’t live to see the film open in theaters. Not until the 1992 Oscars, when Lauch gave an emotional tribute to Ashman, would Disney’s massive audience know that the most beloved film in the world was written by a gay man with AIDS.

Watch Bill Lauch accept the Best Original Song Oscar for “Beauty and the Beast” on behalf of Howard Ashman in 1992:

Ashman died on March 14, 1991, at the age of 40, but Beauty and the Beast — which includes a dedication to Ashman in the closing credits — cemented his legacy. The film not only doubled The Little Mermaid’s box office, it became the first animated movie to receive an Academy Award nomination for Best Picture and won Ashman his second Oscar for Best Original Song (watch Lauch accept the award on his late partner’s behalf above). Inspired by Broadway musicals, Disney’s Beauty and the Beast subsequently became one itself. The stage version ran on Broadway from 1994 to 2007 and included an Ashman song, “Human Again,” that had been cut from the film (though it was included in the film’s 2002 home video re-release). In 2014, Disney hired Condon to direct its live-action remake of Beauty and the Beast, which was initially conceived as a non-musical, until Condon insisted on including the original film’s classic songs. The new movie includes some of Ashman’s alternate lyrics for the song “Gaston,” of which there were many. (“I think Howard just had fun with the pattern, and sat down and wrote dozens of verses, and then they picked which ones they liked best and put them in the film,” says Lauch.) Like its animated predecessor, the remake has already broken box office records and sent thousands of people home humming “Be Our Guest.”

Ashman’s surviving friends and family say that they see Ashman everywhere in Beauty and the Beast: in the wit and charm of Lumiere, the kindness of Mrs. Potts, and the risk-taking spirit of Belle. For them, the film’s success will always be bittersweet: a reminder of a creative visionary lost to AIDS, along with so many others. Had Ashman lived, his influence on the film and stage worlds might have been even more profound. “I always think, Oh God, what would he have done with this or that?” says Lauch. “But that just isn’t possible, and I’m grateful that he did the work he did do at Disney, and that it has had this incredible life beyond his. Whether it’s changed or altered or it evolves into other things, it still comes from what he did — and the things that actually have his fingerprints on them are still there for people to come back and look at. And I think Beauty and the Beast will stand as a classic for many, many years.”

‘Beauty and the Beast’ star Luke Evans on bringing Gaston to life:

Read More from Yahoo Movies: