Beetlejuice and cake in the rain: The wild story behind MacArthur Park

In 1967, the American songwriter Jimmy Webb received a call from record producer Bones Howe requesting a song for the American pop group The Association. Envisaging “a kind of climactic tour de force”, Howe asked for a majestic marriage of pop and classical music comprising “different movements and tempos” and a melody that would prove irresistible to Top 40 radio. As if that wasn’t enough, the track, which could be up to 10 minutes long, should also feature harmonic vocal parts for the band’s six members, various solo spots – oh, and the strings and bows of a full symphony orchestra.

“It comes with the usual caveat,” the producer explained. “I need it yesterday.”

With this, the timeless MacArthur Park was born. Almost six decades after bursting onto the scene, this week the song provides the soundtrack to the memorable climax of Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, Tim Burton’s hit sequel to his classic 1988 horror-comedy extravaganza. Elsewhere, its seven minutes and 30 seconds of splendour have been covered by artists including Donna Summer, Waylon Jennings, Tony Bennett, The Four Tops, Andy Williams, Beggars Opera, and many more. So many, in fact, that one notable database lists almost 200 different versions of the song.

For a tune of such longevity, its composition was fast and furious. Back in 1967, Jimmy Webb went to work for three restless days. “When I surfaced, I looked around, stunned by the storm of dirty Kleenex and rancid beer cans, the dozens of busy, unkempt pages half-stuck together by Scotch tape so they looped over the grand [piano] and touched the floor on both sides,” Webb wrote in his autobiography The Cake And The Rain. “I hadn’t eaten. I had fallen asleep a couple of times at the keyboard and awakened with my face playing a G13 with a demented fourth… I was deep into the score, writing French horn parts and strings, woodwinds, and percussion. During the entire process, I took no drugs of any kind.”

At the end of all that, though, upon performing his magnum opus for The Association the following night, Webb learned that the band didn’t much like the track. But he was unperturbed: “I’ve never cried over a turndown,” he said. “Ninety percent of all songs ever submitted were turned down at least once. Bones Howe was p–ssed [off]. I just went out and bought new jeans.”

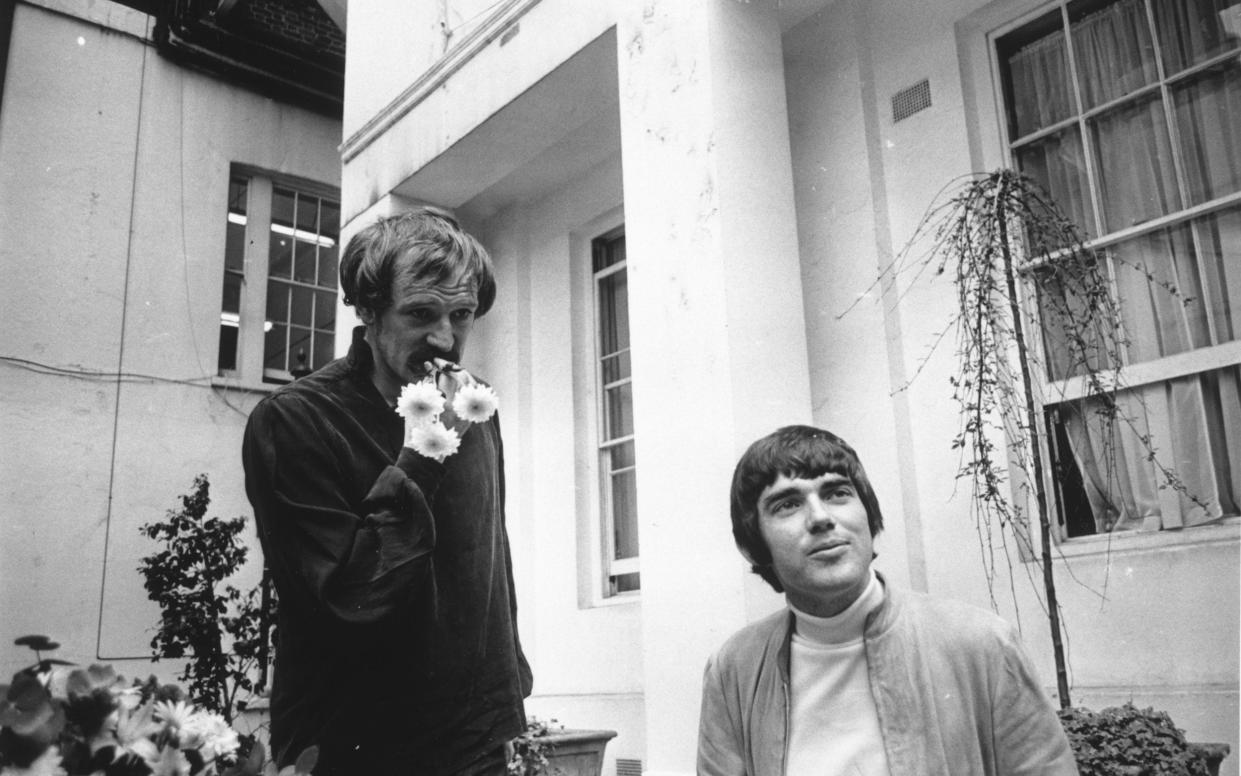

Truth is, though, you can’t keep a good song down. That same year, Webb had made the acquaintance of the Irish actor Richard Harris, a Celtic firebrand with a heart of caramel who smothered the bewildered composer with hugs and kisses at their first meeting. Just weeks after MacArthur Park had been shown the door by The Association, Webb received a telegram from Harris. It read, “DEAR JIMMYWEBB [sic] (STOP) COME TO LONDON (STOP) WILL MAKE GREAT RECORD (STOP) LOVE RICHARD”.

The result of this hectic communique was Richard Harris’s 1968 solo album A Tramp Shining. Comprising nine tracks, each composed, arranged and produced by Jimmy Webb, the LP featured the first ever recording of MacArthur Park. Released as a single in April 1968, the song would go on to top the charts in Australia and Canada, while hitting the number two and number four spots in the United States and Canada respectively. In 1978, Donna Summer’s disco version sold more than a million copies in the US alone.

MacArthur Park itself is that rarest of things – an area of green public space in the City of Angels. Situated between 6th and 7th Street, at the northern border of south Los Angeles, it was here that Webb, a then-penniless songwriter, would meet his girlfriend, Susie Horton, during her lunch break from a job at the Aetna insurance offices across the street. The painful fracture of this romance, at the same spot in 1965, provided the song with its emotional spine. In a lyric resplendent with vivid detail, the opening line – “spring was never waiting for us, girl, it ran one step ahead” – set the tone.

“Everything in the song was visible,” Webb told Newsday magazine in an interview in 2014. “There’s nothing in it that’s fabricated. The old men playing checkers by the trees, the cake that was left out in the rain, all of the things that are talked about in the song are things I actually saw. And so it’s a kind of musical collage of this whole love affair that kind of went down in MacArthur Park. Back then, I was kind of like an emotional machine, like whatever was going on inside me would bubble out of the piano and onto paper.”

Jimmy Webb attributed this lyrical eye for detail to the influence of The Beatles. In 1967, while living in the home of Johnny Rivers (who had signed him to a publishing deal after recording the song By The Time I Get To Phoenix), the pair’s minds were atomised after listening to Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band while flying high on LSD. As the album ended, the house began to reverberate to the sound of a nearby Los Angeles Police Department helicopter. Believing they were about to be raided – incorrectly, as it goes – the panicked young men flushed their not inconsiderable stash down the toilet.

Six years later, Webb went one better – or worse – when an overdose of PCP put him in a coma for 24 hours. “When I woke up, I couldn’t remember how to play the piano,” he told the Big Issue in 2022. “It took me a month to remember.”

Embracing the countercultural Sixties, Webb was rather taken with the idea of being a rock and roller. Attending the pivotal Monterey International Pop Festival, in 1967, he felt a kinship with artists such as Jimi Hendrix, The Who and the Grateful Dead. Critics who misinterpreted his own melancholic and melodic music as being representative of “straight” America propelled him up the wall. In fact, the very first words spoken to him by Glen Campbell, for whom he wrote the monster hits Wichita Lineman and Galveston, were, “When are you gonna get a haircut?”

“The truth is I was a heavy pot smoker, a sexual adventurer, and a hopelessly liberal Democrat who hated the war in Vietnam,” Webb said. “Meanwhile, just like every other kid, my favourite bands were The Beatles and the Stones.” He even declined an offer from the singer and Capitol Records co-founder Johnny Mercer to curate a library of his favourite recordings for the President and his family. “I didn’t think the Nixons would appreciate Frank Zappa’s Live At The Fillmore East, or Little Feat’s Sailin’ Shoes, or Sticky Fingers by the Rolling Stones,” he explained.

But Webb knew that his skill lay not in little red roosters or rolling over Beethoven, but in plucking at the strings of hearts the world over with songs that were lonesome, fractured and evocative. And with Richard Harris as his vessel, he’d found himself yet another perfect foil. The actor had a good ear. In 1967, following a rehearsal for a benefit concert for the American Theatre of Being, at the Coronet Theatre on La Cienega Boulevard in Los Angeles, the pair had retired to a hostelry at which the Irishman taught his new friend a selection of Celtic ballads on the piano.

Their most famous moment, though, might easily have gone unheard. Believing MacArthur Park too cumbersome for an artist best known for speaking rather than singing, Webb came close to deciding against transporting the song’s chunky manuscript of lyrics, charts and sheet music all the way to London. It was only after first whirling through a portfolio of songs he thought might suit the Irishman’s voice that he even bothered to play his as-yet-unrecorded masterpiece. Straight away, Harris began pacing the room. “F–cking tremendous!” he shouted. “Now, Jimmywebb” – he would always call the composer by his full name, as if it was one word – “that’s a song fit for a bloody king! I’ll have that!”

“He made me play it 40 times if he made me play it once,” Webb wrote in his autobiography. “I was shredding my nails. He insisted I tape it instrumentally and then he sang it 40 times.”

Along with 10 other tracks, eight of which can be heard on A Tramp Shining, MacArthur Park was laid down at Sound Recorders studio, in Hollywood, during the festive period of 1967. Alongside a full orchestra, its personnel featured members of the Wrecking Crew, the crack team of session players responsible for (among many other things) Phil Spector’s famed “wall of sound”. Remarkably for a song that lacked corporate funding – after being rejected by numerous labels, the finished album and its towering leadoff single was eventually bought and released by Dunhill Records – there was no cutting corners. Webb and Harris simply picked up the tab: a whopping $90,000.

Yet the recording wasn’t smooth sailing. Recording his parts in January of 1968, in London, Harris sat at the microphone with a pitcher of Pimm’s and one notable technical deficiency. No matter how many times he was asked to deliver the words “MacArthur Park”, he sang the plural – MacArthur’s Park. Despite hours of coaching, not to mention the extensive application of technical sleight of hand, Webb was unable to scrub the pesky, extraneous “s” from the master tape. The possessive would have to stay.

Upon hearing various mixes of the song, Harris also succumbed to a bout of Lead Singer Disease. Enveloped in self-consciousness, at first, the actor believed that his voice towered over MacArthur Park to an unnecessarily dominant degree. As was his wont, he then changed his mind. After listening to the final mix, the opinion came that, no, it was the swells of the orchestra that were drowning him out. This inconsistency continued right to the bitter end; even after the track had been mastered, the actor busied himself requesting changes.

Surprisingly, during the process of recording A Tramp Shining, Richard Harris lost his notoriously diminutive temper with Jimmy Webb only once. Venturing the opinion that Paul McCartney was the chief architect of The Beatles’ success, the composer was met with the outburst, “Bollocks! I hate people who say that! Every c___ in the world thinks he has some insight into The Beatles”. Overwhelmingly, though, the pair shared a warm and collaborative relationship, despite plans to record six albums together eventually coming to naught.

Flush with success, in Los Angeles, Webb bought a mansion in the Valley furnished with grand pianos, a handmade billiards table, and six acres of pools and water features. After recording one more album of Jimmy Webb originals (1968’s The Yard Went On Forever), the four tracks the composer contributed to Harris’s next LP (My Boy, from 1971) would signal the end of their time together.

Despite being remembered by history as the men responsible for a song that spans decades and oceans, to its composer, the strange majesty of MacArthur Park could at times seem like a jewel-encrusted millstone.

For a time he couldn’t seem to escape it. One night at an old LA haunt he was asked the inevitable question: “Would he ever again write anything of the same stature?”

“Never,” he replied. “I’ll never write another MacArthur Park.”