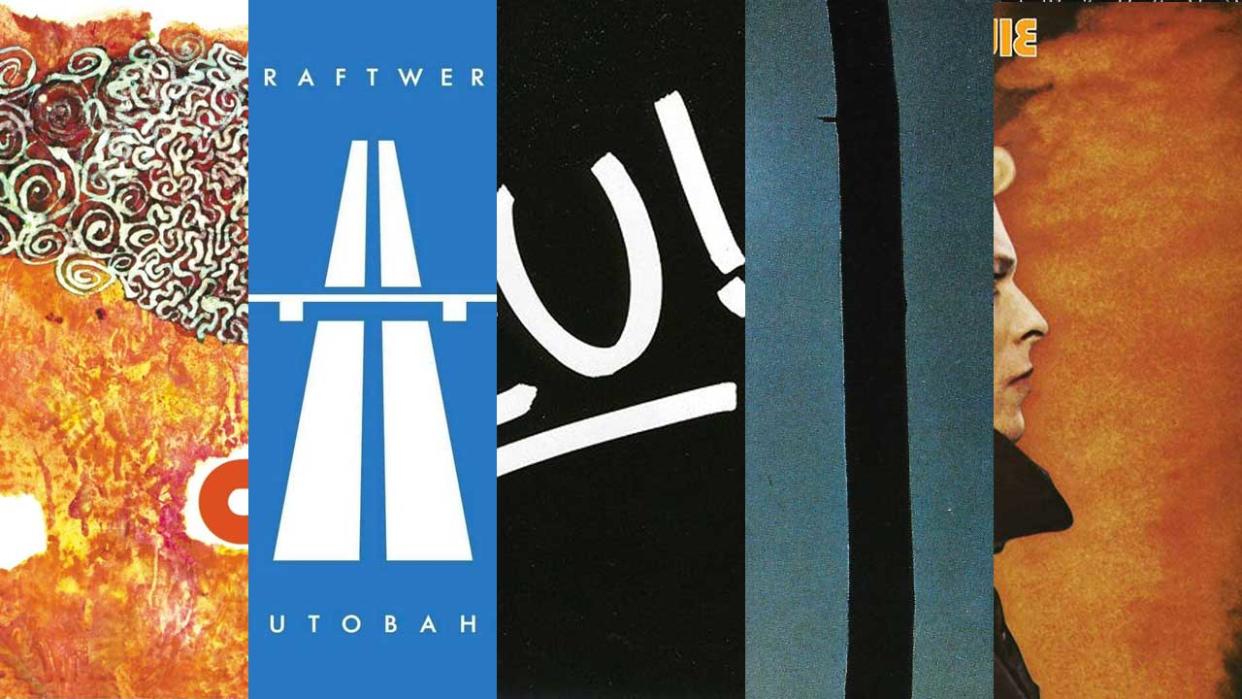

A beginner’s guide to Krautrock in five essential albums

It first crept into Britain in the early Seventies, a little baffled at its reception. When Faust named a 1974 track Krautrock, they were throwing shade at how idiotic the Brits must be to have given a genre that reductive name.

“We thought they were just taking the piss”, they shrugged. Germans preferred the word “kosmische”. And yet the tackier name has stuck, even though the music ranged wildly from prog-adjacent space rock to electronic loops to mantra-like motorik momentum. Kraftwerk didn’t sound like Can; Neu! didn’t sound like Tangerine Dream. Roedelius didn’t sound like La Dusseldorf.

What these bands did share was a keenness to forsake obvious Americanised blues and rock’n’roll cliches and forge a more European, exploratory sound. Aligned to the student protests of 1968, wishing to rebel against traditional German music, they weren’t fussed about song structures, melodies, choruses. They were more impressed/inspired by Moe Tucker’s minimalist beats for The Velvet Underground, and the drone-driven aspects of that band.

Then, as Krautrock’s leading lights ate up the miles across that decade’s autobahn, the declarations of fandom by David Bowie and Brian Eno around 1977 raised the genre’s profile mightily, and a generation, loving Low, dug back into the hypnotic constructs of these radical new roadbuilders.

Can - Tago Mago (1971)

Debate will continue over which is the essential Can album, but their 73-minute-long second covers the most diverse territory and is often cited as one of the most influential albums ever made. That’s not always a good thing: you can hear where Happy Mondays and Primal Scream lazily nicked a few of their baggy grooves from. But Tago Mago’s leaps from loping funk to musique concrete serve as perhaps the closest thing one strain of this thing we call Krautrock has as a manifesto. “It sounds only like itself”, wrote Julian Cope.

Damo Suzuki, Holger Czukay, Michael Karoli, Jaki Liebezeit and Irmin Schmidt improvised marathon sessions in a lofty castle near Cologne; Czukay then cut it into shape. Liebezeit’s drum focus across Halleluhwah is now so familiar (from copyists) that it’s easy to forget how fresh and weird it then was. When an album has drawn awestruck plaudits from both Marc Bolan and Mark Hollis (and Radiohead), you know it must be pinballing around peripatetically.

Kraftwerk - Autobahn (1974)

An unlikely crossover single edit of the 22-minute title track saw Krautrock infiltrating the UK pop charts. A year earlier, Faust’s The Faust Tapes had visited us like a more eccentric John The Baptist (Branson’s Virgin had evangelically charm-bombed Blighty with that album, flogging 50,000 copies at a loss-leading 49p each). For Kraftwerk, this fourth album was transitional, as they shifted personnel and embraced synthesisers and drum machines.

It’s not their best album, but it’s probably their most significant. Little did they realise what a game-changing influence it would prove to be. Reviews at the time dismissed Autobahn as inferior to Mike Oldfield and Wendy Carlos. A Chicago radio station then picked up on the Autobahn single; others called it “sound poetry”. The ultimate sonic road movie had Bowie saying, “The preponderance of electronic instruments convinced me this was an area that I had to investigate further”. More than a diversion, it redirected modern music.

Neu! - Neu! 75 (1975)

Any Neu! album is key to Krautrock’s ascent, but it was their white hot third which nailed the way the genre can use repetition to hypnotise you higher and higher. Michael Rother and Klaus Dinger were both giants in the story of these sounds (their other outlets like Harmonia, Kluster and La Dusseldorf were important players). Now they built a record with one side going ambient and reflective and the other surging and sawing with marvellous motorik and rhythm as a texture.

The tracks E. Muzik and Hero plainly influenced Bowie’s Berlin period and PIL’s best grooves. An album which both worked up a fire and seemed at the same time to be clinically, objectively, looking at that fire and raising an eyebrow – a trope which brighter Brits adopted to knowingly transform pop in the Eighties.

Tangerine Dream - Ricochet (1975)

Rippling out from the West Berlin underground art scene, Tangerine Dream, led by Edgar Froese, had been making strange subterranean noises since the late Sixties. They seemed no more of a solid commercial prospect than, say, Popol Vuh or Amon Duul, but Virgin Records’ backing saw them making waves across the Seventies. Their use of Moog and sequencers was a highly resonant tangent of Krautrock, influencing film scores for decades.

Phaedra and Rubycon were commercially successful, and Ricochet put complex, multi-layered rhythms into the mainstream. It counterbalanced the overt pop bubbliness of Giorgio Moroder, and foreshadowed more recent big-league electronica. A pair of live (with studio tweaks), lengthy, haunting compositions, it sounds remarkably pure even today.

David Bowie – Low (1977)

So OK, it’s only very loosely a Krautrock album, but the evangelism of Bowie and Eno around this era of his work – which took in Iggy Pop’s The Idiot, and of course the frequent references to German culture on Heroes – casts Low as a monolith in the movement’s history. In a nutshell, we’d barely be talking about Krautrock now if the thin white duke and his boffin mate Brian hadn’t banged on about it, converting the impressionable young to its cathartic crescendos.

Station To Station had copped a nugget of Neu!; The Idiot tested the waters further. Low, a watershed record, split itself between concise, fragmentary anti-songs and instrumental synth sighs. From Joy Division to PIL’s Metal Box, from goth to post-rock to techno, the colours of Krautrock thereafter ran through music like veins in a leaf, discernible in all corners from LCD Soundsystem to Stereolab to The War On Drugs. Low was a moment of discovery, a breaking of glass, and that was always the essence and motivation of Krautrock.