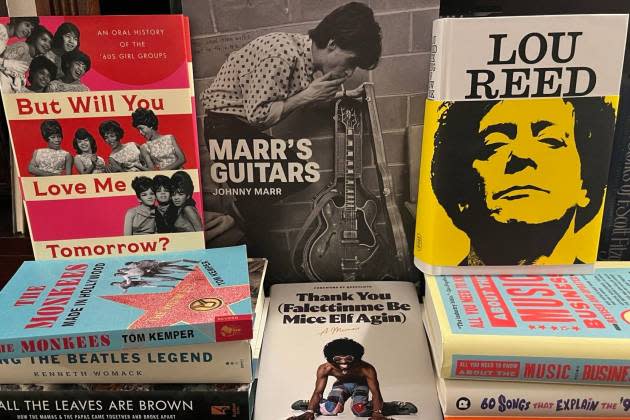

The Best Music Books of 2023: Lou Reed, Britney Spears, Sly Stone, Girl Groups and More

Every year we start off this column in the same way, with a “so many books, so little time” caveat and noting that it represents just a fraction of the fine music tomes released over the past year. And every year, we hope to spread the word on the excellent volumes that we actually managed to finish. The art of the music book is more alive than ever: Dig in…

(Additional contributors: A.D. Amorosi, Steven J. Horowitz and Chris Willman)

More from Variety

“Lou Reed: The King of New York” Will Hermes — Longtime Lou Reed and Velvet Underground fans may take one look at this dauntingly heavy, 500-plus page tome and wonder whether they need to read another book on the subjects — happily, the answer is an unequivocal yes. Despite its heft this volume moves along at a well-paced clip, wisely focusing on Reed’s peak years and moving relatively quickly through his later decades without skimping on them. Hermes dug deep into Reed’s past — interviewing family members, childhood friends, college classmates and others — but the real value here is in his critical insights on the artist’s work and its influence. There are fresh perspectives on the formidable literary merits of Reed’s work — particularly a well-observed passage on the wide range of offbeat characters inhabiting his songs — and his impact on the normalization of musicians in advertising (via his still-cool Honda motorcycle commercial from the mid-’80s). But the greatest insights here are on his towering influence on LGBTQ culture and his huge role in advancing it by pure example — not only in his songs but in his life, from his longtime relationship with a trans woman, the late Rachel Humphreys, to his authentically camp clothing in the 1970s (as opposed to the garishness of the glam-rock stars); that many of the things he did and said at the time seem tame today is a testament to that influence. Some ten years in the making, and citing a dizzying array of other materials, this masterful work is the definitive Reed history.

Britney Spears “The Woman in Me” — For thrill-seekers, this book is filled with all those salacious tidbits that often make celebrity memoirs so juicy and clickable. But there’s so much more beyond the headlines that dominated the press cycle around its release. Written with clarity and self-actualization, the book portrays a much more sympathetic Spears — one who has been consistently beaten down, mercilessly manipulated and, above all, punished by those closest to her. It’s a tale of an American tragedy in which its heroine overcomes the struggle of a broken home to become one of the world’s biggest stars, only to realize that a dream to succeed isn’t enough to shield you from the insidious agendas at play. But in the end, it’s a lesson in redemption and finding freedom in a life pocked by hardship. It’s hard not to see Spears as a victim, and she consistently guides the reader to once again interrogate why the world complacently watched as she suffered. After recounting the horrors of her conservatorship, she ends on a note of hope and as a survivor, one who’s figuring out what it means to finally live life on your own terms. — Steven J. Horowitz

“But Will You Love Me Tomorrow?” Laura Flam and Emily Sieu Liebowitz — Girl group fans, stop what you’re doing right now and order this masterfully reported and compiled oral history of the era and the sound. Named, of course, after the Gerry Goffin-Carole King-penned Shirelles song that was their first hit and a prototype of the sound, the book starts off with the dawn of the girl groups — the Chantels, the the Clickettes — but quickly moves into the Bacharach-David hits of the Shirelles and of course the boom, the Shangri-Las and the Phil Spector-produced hits by the Crystals, the Ronettes, and especially Darlene Love, whose voice is one of the defining sounds of girl groups but was often buried (with characteristic controlling behavior) by Spector under a variety of different names. But what comes across most in these stories is how young these singers were — many were just out of if not still in high school — and the abusive behavior they endured in the brutal music business of the era. All of them were cheated; most were treated horribly; many were Black performers facing the perils of traveling through the segregated South on tour; some were sexually assaulted, and nearly all of them were too young or na?ve to understand how that what was happening was wrong. Also uncovered is the story of Florence Greenberg, possibly the first female modern label owner and A&R person, who founded Scepter Records and steered the Shirelles’ career. Props and a resounding heavenly sha-la-la chorus to Flam and Liebowitz for getting so many of these people — not just singers but songwriters, producers, business executives and more — to tell their stories, and preserving them for the ages.

“Thank You (Falettin Me Be Mice Elf Agin)” Sly Stone — Of all the fallen stars of the rock era, Sly Stone is definitely in the top 5 who seemed least likely to be writing an autobiography at 80 years old. As the founder and guiding light of Sly and the Family Stone, he was one of the most brilliant stars of the Sixties, but as the decade turned, things grew dark when drugs, guns and violence entered the picture; the music got darker too. Sly managed to keep his star aloft for a few more years, but the long downhill slide had begun, and by the late ‘70s he was broke, addicted and adrift — and for the most part, he remained that way. There have been several aborted comebacks, all of them disasters entirely of his own making. So this book, written by a recently-sober Stone with the New Yorker’s Ben Greenman (and the first release from Questlove’s AUWA Books), is not only a welcome surprise, it’s written in a voice that will be so familiar to fans that its first few chapters are like a visit from a long-absent friend. Sly writes like his lyrics — the offhand rhymes and playful turns of phrase, some of which are funky but quaintly dated (“How many bellboys got their bells rung”), others timeless (“When I was old enough to not be too young anymore…”). As exciting and life-affirming as the book’s early chapters are, the second half is tough — first watching him lose everything, then reading his dry accounts of addiction, multiple stints in jail and peripatetic existence.

“My Name Is Barbra” Barbra Streisand — You can’t exactly say Streisand didn’t stretch herself across disciplines over the course of her six-decade-plus career — concert performer, recording artist, actor, director, producer — but the surety of the prose in “My Name Is Barbra” suggests she undertapped herself in at least one area: as a (non-screen) writer. When in the past she took pen to paper — literally; Streisand says she can’t type, so she writes in longhand, it’s been an occasional dip into topical events (see her Variety essay “Why Trump Must Be Defeated in 2020”), but that kind of commentary carried the solemnity you’d expect from her uber-diva rep. Not to say that her autobiography is then completely a barrel of levity. But her sly sense of humor is just one of the disarming things about a book so charmingly conversational, you’d swear that implicit within it is an invitation to come over for a game of Rummikub and some McConnell’s Brazilian ice cream. (Don’t try this at home, of course.) Come for the hundreds or thousands of fairly down-to-earth asides within its 970 pages, then stay for the erudite commentary on movies and music… that just happen to be mostly her own. She offers full, satisfying chapters on films that are as essential to the 20th century canon as “The Way We Were” or as relatively obscure as “Up the Sandbox” that — maybe surprisingly to some — prove once and for all that she was paying as much close attention to her colleagues’ contributions as her own. On the music side, she’s just as objective and candid, offering fascinating assessments of how an “Evergreen” or “Way We Were” came to be… and also admitting she had no idea what the hell Laura Nyro’s “Stoney End” was about. Yes, the sheer heft of the physical edition is daunting, but you won’t wish it was only 600 pages, or 800, or even 960. — Chris Willman

“All You Need to Know About the Music Business: 11th Edition” Donald Passman — Now in its 11 th edition, this book, written by one of the industry’s most prominent and experienced attorneys, remains the single best one-stop for learning about the music business. This latest edition updates many elements of the streaming business, and also includes a very clear-eyed take on AI and music and the still developing legalities around it. Passman’s tone is conversational but also no-nonsense — his conciseness and clarity, as always, break down the complexities of an extremely complex business into understandable elements without speaking down to the reader. Its very nature dictates that it’s hardly a page-turner, but Passman’s style is engaging and his expertise near-unimpeachable.

“Marr’s Guitars” Johnny Marr— Guitar porn of the highest order, this massive, imaginatively rendered and lavishly illustrated coffee-table book is centered around the legendary Smiths/ The The/ Modest Mouse guitarist’s fanatical guitar collection. Marr remembers not only when and where he acquired nearly each of his hundred-plus guitars, but which songs he wrote on them: Although he doesn’t always connect these dots, it’s clear that the tremolo bar on the gorgeous Gibson ES-355 that Sire Records chief Seymour Stein bought him played a huge role in the sound of “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now” and “Girl Afraid” (the first two songs he wrote on it), and the beautiful Gibson electric 12-string almost definitely spawned such janglefests as “Paint a Vulgar Picture” and “You Just Haven’t Earned It Yet Baby.” Non guitar geeks will be fascinated by the memoir and the period photos of Marr through the years — he changed his look as often as his guitars — but photographer Pat Graham has taken a refreshing approach, combining guitar-geek-satisfying full-body shots of the decades-old instruments with close-ups of their rustic details: cracked varnish, tarnished metal hardware, worn wood. What’s almost as striking is Marr’s generosity with his near-priceless collection: While gifting guitars is a traditional act of respect between musicians, he’s loaned out or given away some of the most mouth-watering instruments in his arsenal, including a couple that figure heavily in Smiths lore.

“World Within a Song: Music That Changed My Life and Life That Changed My Music” Jeff Tweedy — The eternal darling of rock critics turns out to be an awfully good one himself. It would be self-serving, of course, to imagine that Tweedy took any lessons from the reams of rave reviews that have been written about his band or solo efforts over the years. This is as (almost) as much personal memoir as it is music criticism, holding in balance autobiographical elements and the truths about pop music we or he hold to be self-evident. You probably won’t even have to be a Tweedy fan in the slightest — although nothing about Wilco devotion will hurt — to find delight in his thoughtful but pithy chapters about why songs as disparate as “Both Sides Now,” “Dancing Queen,” “Takin’ Care of Business,” “I’ll Take You There,” “My Sharona,” Wings’ “Mull of Kintyre,” Rosalia’s “Bizcochito,” Billie Eilish’s “I Love You” and the Replacements’ “God Damn Job” mean something to him. This is a “favorite songs” book that belongs on the shelf next to Dylan’s “The Philosophy of Modern Song,” notwithstanding how Tweedy embraces the first-person approach as much as Dylan avoided it. If anything, Tweedy actually has more of an actual philosophy about songs than his admitted idol: “Loving one thing completely becomes a love for all things, somehow,” he contends — and as sweepingly optimistic a statement as that may be, damn if Tweedy doesn’t make you believe it, or at least aspire to it. — Chris Willman

“Silhouettes and Shadows: The Secret History of David Bowie’s Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)” Adam Steiner — Before discussing Steiner’s focus on Bowie’s antics in Berlin and New York City during the years before his platinum-plated “Let’s Dance” album it’s important to know that he usually writes and edits within the field of poetry. Aching lyricism has given Steiner an unusual edge when it comes to topics such as Bowie and Nick Cave (“Darker with the Dawn: Nick Cave’s Songs of Love and Death”). Here, the biographical history comes via interviews with Bowie’s closest still-living collaborators of that era, but also through an appreciation of his lyrical process, from a poet who knows one when he sees one. Bowie’s noisiest and last truly innovative album before 2016’s “Blackstar,” “Scary Monsters” was ripe with Bowie’s usual insect paranoia and cut-and-paste workmanship. That same album, however, also showed Bowie in a mood to compete and put put “the New Wave boys” and the “same old thing in brand new drag” in their place. Steiner writes potently and poignantly of the artist’s late-‘70s personal turmoil, and comes up with a workaholic inventor at a crossroads who deals with inner madness by spewing bile, grief, the tenants of unrequited love and a goodbye to Major Tom across one tight avant-post-punk-electronic classic. That’s a lot to chew on, and Steiner does so nobly. — A. D. Amorosi

“Living the Beatles Legend: The Untold Story of Mal Evans” Kenneth Womack — The Fab Four had more than a few fifth Beatles (notably producer George Martin), yet none no one was as much of a constant in their lives, or for as long, as Mal Evans, their road manager, confidante, fixer and occasional musical contributor. Womack knows his stuff as a chronicler of Beatles lore with past volumes such as “John Lennon 1980: The Last Days in the Life” and “All Things Must Pass Away: Harrison, Clapton, and Other Assorted Love Songs.” But Womack is also a novelist and gives the little-known biography of this unlikely Beatles bud a sense of epic sweep, examining how a married-with-kids telecommunications engineer with zero music biz background became the Liverpudians’ go-to guy. Even Evans’ last year of life is the stuff of a novel: His wealth of unpublished archives, journal entries and other reminiscences were scheduled for his own book, titled “Living the Beatles’ Legend,” until he met a tragic end so strange that you have to read Womack’s account. Through Evans’ mind’s eye and recollections, and a wealth of fresh interviews, Womack pieces together the days in the life of one of the music business’ most colorful and previously unheralded characters. — A.D. Amorosi

“All the Leaves Are Brown: How the Mamas & the Papas Came Together and Broke Apart” Scott G. Shea — As the friendly face of hippiedom, the Mamas & the Papas blazed across the TV screens and transistor radios of mid-‘60s America in a wash of glorious harmonies and good vibes, but it all turned dark very quickly. After the group’s origins in folk-era Greenwich Village, they found a welcome home in the burgeoning Los Angeles music scene and burned bright for a few vivid months — John Phillips penned some of the most distinctive songs of the era (from “California Dreamin’” to Scott McKenzie’s “San Francisco”) and helped produce the groundbreaking Monterey Pop Festival; Cass Elliott was one of its most distinctive singers and Phillips’ wife Michelle was one of the most beautiful. But it all began falling apart almost as quickly as it came together — Michelle and bandmate Denny Doherty began an affair right when the group’s debut album was released — and it all spiraled in a cascade of jealousy and drugs, and John Phillips went on to become one of the most odious drug casualties in music history. The trainwreck of the group’s existence is recounted in vivid detail in Shea’s excellent history.

“The Monkees: Made in Hollywood” Tom Kemper — What a difference a half-century can make: The Monkees were one of the most successful pop acts of the 1960s but were viciously maligned as a prefabricated Beatles knockoff created purely to populate a weekly sitcom — all of which was true. But in the process the group made some of the most memorable pop songs of a vibrant era and also had one of its most distinctive singers in Mickey Dolenz. Now, in an era where such qualities are an unequivocal benefit if not a virtue, it’s hard to imagine the extent of puritanism the group faced, but Kemper places it all in refreshingly contemporary and judgment-free context, viewing the group’s history through a clear-eyed artistic angle as well as a business one.

“Loaded: The Life (and Afterlife) of the Velvet Underground” Dylan Jones — In capturing such a wrenchingly unsentimental band, English journalist Dylan Jones manages to tenderly capture the love (then lore) that existed with all whom the Velvet Underground touched during their brief existence, the author included. Like many listeners who caught onto the Velvets’ mythology of hard drugs, S&M, discordant music and mercurial poetry at an age when they should still be riding bicycles, Jones found Reed, Cale and company through his youthful devotion to David Bowie, a subject on which the Brit has authored several books. While Nico, Andy Warhol and Edie Sedgewick are given a rarely seen openness, lesser-known names, such as actress Mary Woronov and the late visual artist Duncan Hannah, are so quick-witted and cattily humorous when recounting their personal recollections of the band, you almost don’t care if Jones also uses choice interview elements with actual Velvets, living (Mo Tucker) and deceased (Reed) to tell this full-figured literary tale. — A.D. Amorosi

“Prine on Prine: Interviews and Encounters With John Prine” Holly Gleason, editor — Gleason, a now-Nashville-based journalist, gets started with this collection of published conversations that Prine had over his five-decade career by noting that the revered singer-songwriter actually hated doing interviews. Thankfully, you’d never know it from this compendium, and maybe the man did protest too much: His sometimes acerbic songwriting not to the contrary, Prine came off as a Will Rogers-esque figure who never met a man he didn’t like, and that didn’t exclude the many interrogators that came to his door from the early ‘70s up until his untimely COVID-era passing. A few of the interviewers Gleason rescues from festering in moldy print or lost oxide are celebrities in themselves: Studs Terkel, Cameron Crowe. But he always gave even better than he got from the press, whether he was sharing the secrets of unassuming master-class songwriting or his pork roast recipe. Reading this book of his collected musings is the next best thing to getting just one more song. — Chris Willman

“Leon Russell” Bill Janovitz — To call this exhaustively researched history of a major but often-overlooked rocker definitive is a vast understatement: it’s so thoroughly and masterfully detailed that it’s borderline exhausting, but Janovitz’s work on Russell’s peak years is impressively thorough and illuminating. It begins with his upbringing — and the polio that played a role in his deeply distinctive piano playing style — and moves gradually to his years working with Phil Spector (including an uproarious segment where an uncharacteristically drunk Russell told off the famously abusive producer and disrupted a session for half an hour), and then moves into his peak years as a producer, bandleader and solo artist. The peak years — particularly the chaotic Joe Cocker and “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” tour in 1970 and the horror of drummer Jim Gordon’s mental breakdown — are recounted in such detail that it’s really almost like being there. Janovitz is unsparing in his recounting of Russell’s remoteness and insensitivity as it is to his deep talent and underappreciated influence, and there’s plenty of great, relatively unknown music along the way — especially a fascinating 1967 slab of vintage pop-psychedelia produced, arranged and co-written by Russell called “Land of Oz” by his stable of studio musicians (under the name Le Cirque) that’s not even on streaming services. Truthfully, the book is so thorough that we ran out of steam in the mid-‘70s (around the same time as Russell’s solo career), but it’s a worthy and Phd.-level history.

“60 Songs That Explain the ’90s” Rob Harvilla — This veteran of the Ringer and the Village Voice curates a Spotify music podcast based on the multi-cultural mien that made the ‘90s iconic, tying its tunes to culture, both then and in the present. Harvilla knows what made the mess and minutiae of the 90s tick and twitch, and brings his humorous yet incisive storytelling to Britney Spears, Guns N’ Roses and the sad and broken legends of Tupac Shakur and Kurt Cobain. If you never really knew the correct lyrics to Hole’s “Doll Parts,” Harvilla rights that wrong; if you never really appreciated “I Will Always Love You,” he explains why you’re wrong not to adore Whitney Houston. If you ever forgot the deep spiritual bliss and interpersonal connection you got rattling through somebody’s CD collection or making a lover a mixtape, Harvilla brings it all back home, tenderly. — A.D. Amorosi

“Magic: A Journal of Song” Paul Weller with Dylan Jones — Weller, founder of the Jam and the Style Council, has a niche but fanatical following that will find a wealth of catnip in this lavishly illustrated book, which combines photographs from across his career with reminisces of the songs, the lyrics and their context. More of a career history than a personal one, Weller keeps his focus on the songs and the musicians, and the photographs show that the look of Swinging London, which he experienced as a child from the distance of suburban Woking, has never left him.

“Sondheim: His Life, His Shows, His Legacy” Stephen M. Silverman — Since his passing in 2021, Stephen Sondheim has had no shortage of tributes. Along with his final, posthumous work, “Here We Are” (currently playing off Broadway), Sondheim musicals such as “Merrily We Roll Along” and “Sweeney Todd” are smash, sell-out hits on Broadway. “Stephen Sondheim’s Old Friends,” with Bernadette Peters, is running on London’s West End. Throw a rock in many major cities, and you’ll hit a revival or road tour of “Assassins” or “Company.” Beyond spending thousands of dollars to see these shows, the next best thing is this glamorous coffee table biography from Silverman, who knows the lay of the land and puts Sondheim in only the best light. This large volume offers some critical dissection of the composer-lyricist’s life and work, peering into the process of lesser-known Sondheim musicals such as “Anyone Can Whistle,” “Passion” and “Pacific Overtures.” Mostly though, the volume brims with archival photos of an artist who most shied from the camera, along with rare snaps of past productions such as “Follies,” “A Little Night Music” and his earliest Broadway triumphs, “West Side Story” and “Gypsy.” — A. D. Amorosi

“Material Wealth: Mining the Personal Archive of Allen Ginsberg” Pat Thomas — Along with having witnessed the best minds of his generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked and burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night (yes, I read “Howl” a million times), Allen Ginsberg was something of a packrat who kept seemingly everything that passed through his hands. Along with being an archival music producer and liner-note writer, Pat Thomas has delved deep into the psychedelic culture of Ginsberg’s angel-headed hipsters by penning books like “Listen, Whitey! The Sights & Sounds of Black Power 1965–1975” and a Jerry Rubin biography. Here, he has dug deep into Stanford University’s Ginsberg collection and came up with a wealth of worthy goods. That means everything from a 1974 concert ticket for Bob Dylan and the Band — with Yoko Ono’s telephone number scrawled on the back — to a poster for Patti Smith’s first-ever poetry reading from 1971 at St. Mark’s Church. There are corny but still-relevant Yippie political rants, from John Sinclair of the MC5 to a rare dissertation on Dylan’s “Idiot Wind.” As Ginsberg was something of an amateur photographer and all-around gadfly, there are photos of Iggy Pop, Marianne Faithfull, Lou Reed and more among his souvenirs. And because Thomas can’t resist a good CD tie-in, he produced and is releasing (in March 2024) “Material Wealth: Allen’s voice in poems and songs 1956-1996” featuring Ginsberg backed by Dylan on “Do the Meditation Rock” (1982), by Paul McCartney, Lenny Kaye and Philip Glass on “The Ballad of The Skeletons” (1996), and more. — A. D. Amorosi

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.