'Big Mama' Thornton's Rock Hall induction highlights influence of Black female performers

Rock 'n' roll's godmother, Willie Mae "Big Mama" Thornton, will finally be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame on Oct. 19.

The event will be held at Cleveland's Rocket Mortgage Fieldhouse and will stream live on Disney+, on Hulu the next day and, eventually, as a separate ABC special.

By 2025, many influential Black women in rock's history, including Elizabeth Cotten, Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Thornton, will have been enshrined in rock's Hall of Fame.

Over 40% of the Hall's inductees since 2020 have been African-American acts and executives.

The move represents how representational equity spurred by 2020's racial and social upheaval, more so than a cyclical swing of interest in Black contributions to rock 'n' roll's lineage, is keying an era of Hall inductions.

Seen through the lens of evolutions occurring on the ground in Music City during the same time frame, it has fostered an unexpected set of benefits highlighting exactly what John Sykes, chairperson of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Foundation, means when he notes that "Rock & Roll is an ever-evolving amalgam of sounds that impacts culture and moves generations."

How Nashville benefits from the Rock Hall's inclusionary practices

Foremost, in Nashville, the past decade has seen rock- and stringed-instrument-inspired Black female performers familiar to Music City, such as Rhiannon Giddens, Brittany Howard, Allison Russell, Adia Victoria and Yola, become bellwethers of excellence in the music industry.

In a July 2023 Tennessean feature, Victoria stated that she viewed the blues as "the most valuable heirloom passed down to (her) as a Southern Black woman. The appropriations of the blues that have and continue to happen over the past 50 years symbolize colonizers getting too comfortable and familiar with (the blues). Replication of Jimi Hendrix and Robert Johnson's guitar licks and solos does make you proficient and copying styles — it does not equate with being a 'blues person.'"

"The blues occupies a sacred cultural place in my body that comes from other Southern Black folk's blood, sweat and tears, refining a sound and style for centuries," she says. "White people are audacious to believe there should be any ease in claiming (the blues). They claim it because they have — in many ways — removed Black autonomy from artistic genius."

Reclaiming that excellence couples with a fascinating historical note about the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame's inductions to present an intriguing new dynamic.

Creating a restorative moment

The Hall of Fame's only eligibility prerequisites for induction are that 25 years must have elapsed since the release of the nominee's first record and that the recording artist and bands have "influence and significance to the development and perpetuation of rock and roll."

For the first two decades of the Hall's existence, its inclusion of Black musicians and executives mirrored that of the present era. However, the institution's own regulations caused the shift in popular Black acts' musical tastes around 1975 from rock-inspired sounds while retaining the genre's visual aesthetics — and embracing disco and rap instead of new wave, punk and other rock subgenres — perhaps making those artists' contributions feel worthy of induction.

With groundbreaking performances of songs like 1968's "Ball and Chain" and 1952's "Hound Dog," Thornton not being included alongside Elvis Presley, James Brown, Little Richard, Fats Domino, Ray Charles, Chuck Berry, Sam Cooke, the Everly Brothers, Buddy Holly and Jerry Lee Lewis in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame's inaugural 1986 induction class feels incomplete.

Rock's Black female progenitors are not available to discuss the power of the moment. They were all inducted posthumously. Sister Rosetta Tharpe passed away in 1973, Thornton died in 1984 and Elizabeth Cotten died in 1987.

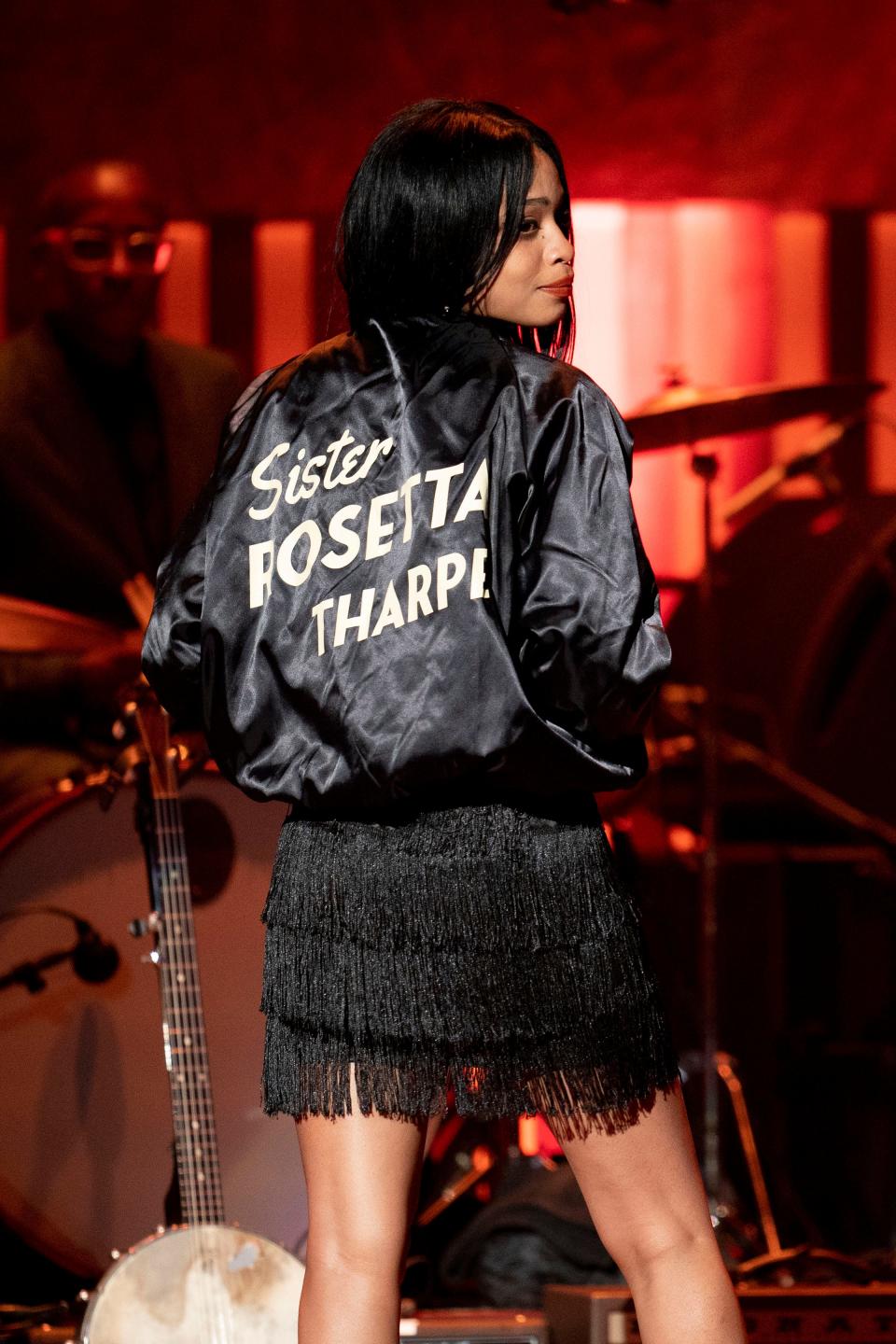

Bittersweetly, through the magic of celluloid and method acting, 2022's Baz Luhrmann-directed "Elvis" biopic saw now-deceased Nashville-based actress and blues performer Shonka Dukureh portray Thornton, while the previously mentioned Yola played Sister Rosetta Tharpe.

Thus, The Tennessean can create a decisive multi-generational and restorative moment by having Yola discuss artists like Thornton and Tharpe, mainly because of their quasi first-person knowledge and lived experience.

The 'difference between appreciation and appropriation'

Yola finds it "fascinating" that four decades have elapsed between the induction of the Rock Hall's inaugural class and the unification of the genre with its "seminal foundation" via acts like Thornton.

"There's a difference between appreciation and appropriation," she says. "Add in that 'Big Mama' Thornton had a No. 1 single and that level of influence but died penniless and it's even worse. It's essential to canonize and commemorate people as much as we profit from their art and music."

Rock is a genre and inspiration that intersects secular and spiritual influences. Thus, it is best when presented as a musical conversation about contradictions and social conflicts. Comfort, via race, in understanding and appreciating lucrative approaches to those creative conflicts has benefitted more white artists than Black ones in recent years' Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductions.

However, if the Hall was less intrigued by how danceable R&B and hip-hop offered answers to America's social decline, to Yola the 2000s could've easily been an era where timeless Black female rock inspirations were considered for induction.

In relationship to this point, Big Mama Thornton was a Black Christian woman who wore a suit jacket, tie and cowboy boots and was often associated with coarse language, lewd behavior and public intoxication.

To Yola, the unwillingness to be inclusive earlier presents a situation where the "gargantuan and profound foundational erasure" of Black contributions and a "foundational embrace of Eurocentrism" could've occurred.

As a woman born in Somerset, England, Yola's awareness of how Eurocentric influences inspired by Black American creativity is less a "reductive" notion and one more representative of the "full wholeness" of namely the African-American female creative lens is profound.

"Obviously, we've got to (get Black women into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame) quickly," says Yola, with the slightest air of humor in her voice.

A 'genre-fluid modern vintage' evolution

Yola's keen to mention Beyoncé's "Act II: Cowboy Carter" album alongside her forthcoming EP release "My Way" (and work including Alice Randall's "My Black Country" project) as expanding a half-decade of seminal albums — 2018's Smithsonian Folkways banjo reclamation project "Songs of Our Native Daughters," Giddens' own three solo albums, Brittany Howard and Adia Victoria's two solo albums apiece and Allison Russell's award-winning duo of releases among them — as representative of a "genre-fluid modern vintage" series of releases where seminal rock influences rooted in what is now an entirety of Hall of Fame level influences, has emerged.

The "Stand for Myself" album creator presents a now-shifted paradigm where, for the past 25 years, Black women have been told that while their Blackness is not monolithic in scope when they creatively paint outside of a narrow set of expectations, they must again be closed in by monolithic expectations.

"All of us have grown from being told that we should stick to singing because we had no business picking up our instruments to being told that we're only artistic within a singular concept or genre. (These inductions prove) that this doesn't need to apply anymore.

"You can't invent something that already exists. A counterbalanced restoration of music's history allows for popular music's origins to surface as Black women are evolving it again."

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Rock Hall of Fame induction spotlights 'Big Mama' Thornton's influence