"It’s the biggest project I was ever involved with." How Steve Hackett made Genesis Revisited II

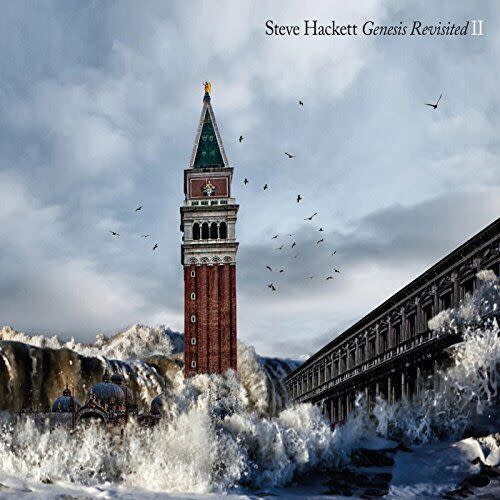

Back in 2012, Steve Hackett followed up his 1996 album Watcher Of The Skies: Genesis Revisited with a much larger undertaking, the star-studded Genesis Revisited II. Prog sat down for lunch with him at the time to get the inside story....

Steve Hackett sits in the bar of a London hotel and casts a glance towards his refreshment of choice. “Look what it’s come down to,” he says with mock ruefulness. “At one time it used to be a Scotch and Coke. Now it’s a weak decaf cappuccino. Not good, is it?”

The moonshine intake may have calmed down, but the workload and the output certainly haven’t. One of Britain’s most prodigious guitarists continues to write, tour and record at a rate that would challenge many a musician half his age. At 62, and looking unnervingly almost the same as he did 20 years ago, Hackett is on a hot streak.

No sooner have he and Chris Squire delivered the Squackett album A Life Within A Day, and seen its title track scoop the Anthem trophy at our Progressive Music Awards, than the finger-tapping guitar godhead is back, breathlessly delivering the double CD Genesis Revisited II. It’s been a race to the finishing line, but one of the most eagerly awaited albums in recent prog history is now with us, and what a mighty beast it is.

“With the Squackett album, there were other things going on at the same time, but that took four years,” muses Hackett. “This took from January to August, and considering its Wagnerian proportions, probably the longest album anyone’s ever done… it’s the biggest project I was ever involved with, but it was recorded in a compressed amount of time. There were a lot of balls in the air.”

To complete nearly 150 minutes’ worth of reinterpretations from his Genesis years in such a slender timespan is a gargantuan achievement indeed, especially with guest appearances from the likes of Steven Wilson, John Wetton, Simon (son of Phil) Collins, Neal Morse and Nik Kershaw, among a cast of dozens. As he says, with justifiable pride: “It’s like the whole of the music business is on it, saying, ‘We like

this stuff.’”

That’s before you mention the multi-format release orgy around the project, with a two-CD digibook, a quadruple vinyl edition and, of course, the digital incarnation. And yet, 16 years on from Watcher Of The Skies: Genesis Revisited, the unreasonable but undeniable question on the lips of many fans will be: ‘What kept you?’

“I wasn’t sure if I could justify it,” says Hackett, thinking back to the period after

the first album appeared in 1996. “I wasn’t in a position [to do another] at that point, especially when Genesis was firmly in existence. I feel we’re in a different era now, where the nice thing is, it seems as if music without limits is the new description of what progressive was all about. I’m very happy to subscribe to that.”

As before, there’s no intention to better a catalogue created during his Genesis tenure, which spanned seven years and ended all of 35 years ago. “I wanted to enlarge it, expand it,” he says, “so that occasionally, even though there’s not a real symphony on it, at times it has the panoramic sweep of that.”

The new set drills down deep into the material Hackett created with his bandmates, with new versions of such staples as Supper’s Ready and The Musical Box, plus four songs that he describes as “Genesis branches”, written for and even rehearsed by the group but never recorded.

“The reason it turned into two albums was that I had one idea of how it should be, and I’d chosen the songs and agreed that with Thomas Waber at Inside Out Records. Then I spoke to Jason Day at EMI, and he said ‘You should do songs where the guitar part is absolutely crucial to the plot.’

“I thought, ‘Yes, he’s absolutely right, he’s given me a truth there.’ I was going to try and be magnanimous about it and step back and say, ‘I just want to do the best songs.’ But I ended up doing two albums so that there’s plenty of guitar, and the other songs where there are not guitar heroics going on, where we’re all accompanying.

“Originally [in Genesis], it would be three 12-string players all sitting down together. I did all of those parts for this, with two exceptions. On The Return Of The Giant Hogweed, from Nursery Cryme, I’d played that a couple of years earlier at the High Voltage Festival with Transatlantic. I guested with them for their encore. Roine Stolt from The Flower Kings and I swapped phrases for that.

“I said, ‘Would you like to record this song, with Neal Morse on vocals?’ He did a great job singing, Roine sent back a solo and I said, ‘I don’t feel the need to fire salvos across all of that – why don’t we just let it run?’ So I gave him the floor for that. Similarly with Steve Rothery from Marillion. At the end of The Lamia, he kicks off the soloing and we do alternate phrases.”

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about the myriad contributions to the album is that they were all done as favours. “So much of it had to be done on location,” explains Hackett. “The idea of bussing everyone in to London was never going to be a goer, and a lot of people prefer to work at home in their studio, as I do myself. If people want me to be on their albums, normally they’ll send me something and most of the time I just do this for love, basically. I do it for the crack. I always think I play better if there’s no money involved. Use it if you like it, or cover the engineering fees.

“So we worked on a barter system with this. Lots of people working at home, different teams working at the same time, two drummers being recorded at the same time, while I’m off frantically trying to finish my guitar overdubs and vocals for the few things that I did sing. But I wanted to sidestep the vocal role here. I didn’t think it was about me. I thought what it was really about was 35-odd people who show up on this thing.

“Roger King, the engineer, I have to say, I can’t sing his praises highly enough. It was a hell of a lot of work for him. I saw him turning various shades of green towards the end. He was doing 12-hour days, as I was, to try to bring it in on time, and frankly I was amazed. We went over the schedule by two weeks, which isn’t bad.”

In his unassuming way, Hackett clearly likes to leaf through these most widely read pages from his extremely varied and expansive career, without being defined by them. “I like to think I’ve moved on since I left Genesis,” he says. “I try to cover every known genre. I did a classical album a while back that had six pieces of Bach on it. But you can be a musical time machine – you can go back, you can go forward, move to other countries, work in South America. It’s one of the things I do: I’ve worked with guys from Azerbaijan, I’ve been on tour with Hungarian fusion guys. I don’t have prejudice. Don’t disparage any genre because at some point, someone will change your mind.”

One of the features of September’s Prog Awards was the cordial conversation Hackett was seen to enjoy with Tony Banks and Mike Rutherford, who were on hand to collect the Lifetime Achievement gong. “Socially, between myself and the Genesis guys, it’s been warm for a long time,” says Steve. “But in answer to the inevitable question, ‘Why aren’t you involving the rest of the Genesis guys?’ [which your reporter hadn’t even asked] there’s always been a resistance to any attempt that I’ve had to involve them in anything for years. Other than the odd charity gig which we managed to do together in the early 80s, but that really is a very long time ago.”

But Hackett is more than happy to champion the creative roots of a style that continues to be woefully, almost wilfully, misunderstood in the mainstream media.

“I was interviewed at the awards for BBC2, and the interviewer was saying, ‘Well yes, but wasn’t it all about swords and sorcery, dungeons and dragons?’ and being very dismissive. I gave a much longer interview than the five seconds I got on camera, but I was saying it covered classical, jazz, pop, rock and social comment. Yes, there was pantomime and humour, but nothing was off limits – it did attempt to be everything.

“I feel as if I’m answering this list of charges,” he says calmly. “If Selling England

By The Pound in 1973 was an album that drew John Lennon’s interest, I think that was pretty good going. We were one of the bands he was listening to at that point, he’s on record saying that, in the WNEW interview. So I can’t disparage the early stuff, although I suspect the other guys in the band try to draw a veil over that and say, ‘That just appealed to students.’ Well, it also galvanised other musicians, so for me, that’s the real deal.”

Brian May, Eddie Van Halen et al, step forward.

So what sort of memories were conjured by volunteering to revisit the 1970s? “I think good and bad,” says Hackett matter-of-factly. “A great positive was that Gabriel called me up first of all to join Genesis, I was welcomed in as a full songwriting partner, and that was the band’s strength, that we were a songwriters’ collective. It’s the co-op, here they come.

“The term progressive was not in common parlance at that time. Latterly, everything we did during that period has been described as that. But there were these great collisions of styles going on, unlikely constructions that shouldn’t really have worked, songs that were allowed to meander, peter out and then come back. And there was not the emphasis on dumbing down that became so much a part of the video era, where in a way you had an extended Muppet Show going on everywhere.”

Tickets are selling briskly for Hackett’s Genesis Revisited II UK tour dates next May. “It seems to have gone through the roof already, so that’s lovely. It’ll be with a visual presentation, with lights and screens. Nurse, the screens!

“I’m not recreating the way it looked at that time – it’s new visuals and a new cast, of course. I’m anxious that it doesn’t present itself as a 70s show. The music from the 70s is where the similarity ends, I like to think, even though it was a golden era for us.”

With his own new selection of songs from those days back in the ether alongside the work of current bands bearing clear hallmarks, Hackett can be gratified about a certain legacy, and he is. “Bands like Muse and Elbow obviously have progressive roots,” he says. “I think we’re affecting the mainstream. Guys like me and my ilk, my ne’er-do-well pals, suddenly we’re the professors of prog. Weird, isn’t it? And yet for a while, it was a four-letter word.”