How Black Actors Broke Through in Old Hollywood — Day to Day, Role to Role

Before the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures opened its doors in 2021, even senior staffers were surprised by the depth of Black film history that dwelt in its archives. Looking through the film posters and memorabilia from race movies of the early 20th century, co-curator Doris Berger found herself amazed and chagrined. She had stumbled on a treasure trove and heritage she knew little about.

Berger is not alone and her experience isn’t surprising. The foundational titles most of us know and gravitate to first when we think of Black film tend to be the earnest classics of the 1960s, the blaxploitation movies of the 1970s, and the indie Black cinema of the 1980s and 1990s.

More from IndieWire

Lena Horne Inspired Better Black Images Onscreen - but Losing This Role Ended Her Hollywood Career

As Black History Month Ends, Here's the Case For Its Reboot: New Stories and Fresh IP

In those archives, Dr. Berger recognized a rich history screaming out for greater attention. The result was an exhibition, conceived and produced in partnership with National Museum of African American History and Culture film and photography curator Dr. Rhea Combs: “Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898 to 1971.” Now on display at the Detroit Institute of Arts through June, the show builds on decades of Black film scholarship, and is spectacular proof that Black artists created important, intriguing work, despite extraordinary barriers before and during the Hollywood’s vaunted Golden Age of the ’20s, ‘30s, and ‘40s.

Today we have more resources than ever to explore what these performers accomplished, and how they made art and made change. IndieWire talked to film scholars, curators, and several descendants of early Black film performers about this crucial period. Their stories about what happened behind the scenes are as telling as those projected on screen — and advance a more complete history of American film.

Movies: A Vehicle of Black Ambition

One thing is clear from any angle: Black Americans have been attuned to the power and the pleasures of visual storytelling since motion pictures were first projected in the 1890s. And from the beginning, they looked at it as a potential vehicle for social change. No less than African American educator and leader Booker T. Washington recognized the significance of motion pictures, using the medium to promote the Tuskegee Institute. He admired the power of entertainers. Of famed vaudevillian Bert Williams, who would become a star of Black film, Washington said: “He has done more for our race than I have. He has smiled his way into people’s hearts; I have been obliged to fight my way.”

That sense of possibility is striking. The barriers found in other industries were present in the nascent movie industry, but the birth of film was also a time of creative fervor and promise. Beginning at the turn of the 20th century, there were (at least) two film industries emerging in parallel but also eventually in tandem: the well-funded and white-dominated studio-driven establishment and Black independent film, exemplified by the work of Oscar Micheaux and Spencer Williams.

Black artists became masters of playing the inside and outside game, working within and outside of the mainstream infrastructure. As Rhea Combs explains, the systems were porous: “There was obviously this very robust independent film industry happening. African American film producers were creating films specifically for African American audiences.” And “there was a conversation and a cultural moment.”

An overlap starts happening between the black independent film scene and the white studios. This, Combs says, becomes more apparent “when talkies come into place, and Hollywood becomes an avenue in which these actors are able to work.” Combs describes an emerging “sort of ecosystem” that includes a “mechanism or environment of performers — dancers, actors, singers — that was being recognized by these maverick independent film producers who are doing this on a shoestring budget. And white producers acknowledging that there is this hunger from Black audiences for these films.”

In mainstream white films, in the early decades of the 20th century, the ugly truth is that racist depictions were ubiquitous. Movies of the 1910s and 1920s often included white actors in blackface, in what Ralph Ellison, writing for the NAACP, recognized as “subhuman portrayals.” The 1915 blockbuster silent film “Birth of a Nation,” with its lost cause revisionism, demonizing Black men and valorizing the rise of the Klan, is the most infamous and egregious example. But the practice was widespread. The first talking feature, “The Jazz Singer” centers a white artist, played by Al Jolson, who desperately yearns to perform black music and does so in burnt cork blackface.

Through the 1930s, Hollywood also reinforced their distorted version of Blackness by restricting Black actors to comic and subservient roles and through direction that demanded that Black actors perform stereotypically exaggerated expression and movement. But there’s something revealing even in these troubling images. As projections of power and ideology, early Black Film performances produced within Hollywood provide access to a history of ideas that few resources can provide, even when it’s a distorted African American experience refracted through white eyes.

As Academy Museum director Jacqueline Stewart argues, looking beyond those mainstream distortions, film preservation can be a lens through which to “recontextualize Black history” and to “recover ideas about Black artistry” and agency and find joy in small victories. Film scholar Donald Bogle’s recommendation and reading of the 1934 version of “Imitation of Life” is one example.

In addition to a multidimensional performance by the Black actress Louise Beavers in the role of Delilah, a contentedly submissive housekeeper to a widowed white single mother, there is something revealing in this white fantasy of interracial comity. The two women raise their daughters together and the white woman starts a pancake business based on the Black woman’s family recipe and labor. Delilah declines even the small fraction of ownership she’s offered and doesn’t want her own home though she can now afford it. It’s a delusional vision of voluntary Black subservience and racial capitalism that some scholars find repugnant. Still, as Bogle contends, in the portrait of the light-skinned daughter who rejects a life of second class citizenship you see inklings of racial injustice driving the younger woman’s unhappiness.

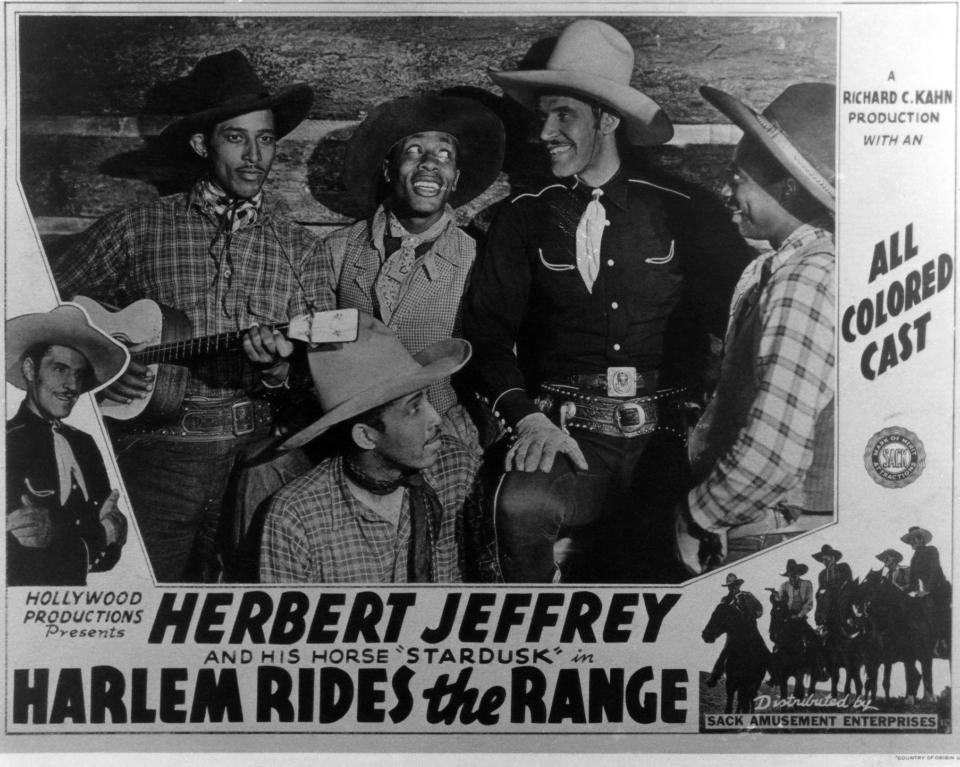

Thankfully, as unintentionally revealing as they were, white dominated images from studio films aren’t the only ones from the period. Beginning in 1919, independently produced “race movies” provided a counterpoint — Black-cast movies which centered Black performers and stories, often with an explicit aim of racial uplift but also in service of Black joy and entertainment. Many were Black versions of popular Hollywood genres like Westerns and musicals. Others were more ambitious. You can see this contest of ideas most clearly in “Within Our Gates,” Oscar Micheaux’s silent film rejoinder to Griffith’s racist epic “Birth of a Nation.”

Though Micheaux is the best known of these groundbreaking Black filmmakers, there were dozens of Black film companies by the 1920s. Even Lena Horne, who was to become a major studio star for MGM, made her debut in a mostly Black cast independent feature, 1938’s “The Duke Is Tops,” by Million Dollar Productions (later retitled “The Bronze Venus”), produced, and co-directed by its star, Black actor Ralph Cooper.

If you aren’t familiar with the stars and titles of early Black independent cinema, you aren’t alone. For decades, much of the history of race movies was thought lost or inaccessible or they were just overlooked, but these films are increasingly available online in digital streaming archives like Kanopy, Criterion, and on Youtube. Other titles are available via DVD. One of the great new resources on this history is the excellent documentary, “Oscar Micheaux, The Superhero of Black Filmmaking” (2021).

Within the Hollywood studio system, much of early Black cinema involvement was driven by the popularity of Black art in other forms. As Fordham professor Michele Prettyman explains, Black cultural expressions such as jazz and vaudeville were wildly popular in the United States in the early 20th century and abroad. At the dawn of the studio system, moguls were eager to capitalize on the magnetic Black cultural power on display in legendary spaces like Harlem’s Cotton Club, despite the challenge of Black stardom in a time of both informal/de facto and formal legal segregation. Even at the Cotton Club, performers dominated the stage but with few exceptions, Black people weren’t allowed in the audience.

Hollywood in the Golden Age was a mass of similar contradictions. Black musicians and dancers such as Fayard and Harold Nicholas commanded attention on the stage and became some of the cinema’s first and most revered Black stars. The brothers’ virtuoso dance performances in “Stormy Weather” and “Down Argentine Way” are a source of great pride for the family members who are the caretakers of the Nicholas Brothers’ legacy. As Nicole Nicholas describes, “when they were in their heyday, they were appreciated. They were beloved.”

Fayard Nicholas’s grandaughters remember him talking about how their acclaim and popularity was something akin to that of the Beatles with “people lined up” and screaming fans “when they came off the airplane.” But, that privilege only lasted for a time. Eventually, “things would change.” At other times, “the sting of racism” was so sharp they felt safer to live abroad, “because Europe was much kinder to them than the United States.” There are Nicholas brothers home movies in “Regeneration” dating back to that time in Italy, when Fayard’s son, Tony Nicholas (Cathie and Nicole’s father) was five.

Like Rosa Parks, Lena Horne Was Chosen

No one epitomizes the evolving politics and possibilities of Black participation in Hollywood’s Golden Era better than singer and actress Lena Horne. Her rise is inextricably intertwined with the events and turbulence of the day.

Just after the United States entered World War II in December 1941, the Black press and advocacy organizations began touting “Double Victory” for victory abroad and victory at home — Black soldiers hoped to parlay their military service into advances toward social and economic equality.

Mass media was also a battleground. Many in Hollywood and in the government believed that America’s best export was its movies and recruited industry to boost morale with Frank Capra aiding the war effort. Meanwhile, as the Nazis made inroads in Latin America and North Africa, Fascist propaganda from the Axis powers aimed to discourage Black soldiers — Imperial Japan even began a shortwave radio campaign aimed at an African American audience, with the message “No one’s gonna lynch you here,” and Germany dropped leaflets claiming “there have never been lynchings of colored men in Germany” in explicit contrast to the United States.

This was the context for Lena Horne’s rise and the 1943 release of two star-studded musical films that were a high-water mark for Black participation in their time: “Cabin in the Sky” and “Stormy Weather.” That year, Rex Ingram would also portray a Black allied soldier in the Bogart war movie “Sahara.”

Amid this media battle for hearts and minds, and as Black leaders pushed for change on screen and behind the scenes in production, the making of America’s first Black sweetheart of cinema was a calculated and politically charged affair. When 1940 politician and 20th Century Fox board member Wendell Willkie joined with the NAACP‘s Walter White on a pressure campaign to break the color line with the all white movie industry unions, the single studio to say yes, “we’re going to try and put a Black face out front,” was MGM. The face they chose was the young songstress Lena Horne.

As Donald Bogle explained in his book “Lena Horne: Goddess Reclaimed,” Walter White, the Executive Secretary of the NAACP was asking studio heads to depict African Americans in “a new way.” For civil rights leaders, Horne would become a kind of “test case” for how that would work. She was chosen by Hollywood moguls and activists, for what her granddaughter, screenwriter Jenny Lumet, characterizes as “a lot of very, very constrained and heavy and conflicting reasons” — in part “certainly because of her physical self.” With what was repeatedly described back then as “cafe au lait skin,” Lena was not someone who could pass for white; rather she was simultaneously visibly Black while fitting prevailing European ideals of beauty.

Then there was what they called “her bearing,” which radiated an ineffable upper class quality. The studio loved that she “spoke like a duchess.” The 23-year-old also had a squeaky clean image, and was as relatable to white folks as any Black woman could be in that day.

So, like NAACP secretary Rosa Parks, who would become a catalyst of the Birmingham bus boycott a decade later in 1955, in 1942 Lena Horne was chosen to represent and help advance the Negro cause (the same year Parks became secretary of her local NAACP chapter). What we now decry as the symbolic politics of respectability were carried in her body and her face. As a result, as Bogle says, Horne “is given the studio build up. She’s really the first Black woman in Hollywood to be fully glamorized. And fully publicized.”

The behind the scenes politicking and choreography remain vivid to her relatives today. As Lumet recounted in conversation, it was an enormous pressure to put on a vulnerable young mother.

Even as a newcomer to the dream factory, Lena Horne was aware of the sky-high stakes attached to her rise, so much so that she called in the big guns when it was time to make a deal. That meant family. When Horne signed her first MGM contract in 1942, her father took the lead negotiating the terms. Edwin “Teddy” Fletcher Horne Jr. was a prosperous hotel owner and the so-called “Black sheep” of an elegant and storied, Black establishment family descended from a close relative of the slaveholding, secessionist Vice President John C. Calhoun. (Lena Horne’s daughter and Jenny’s mother, Gail Lumet Buckley, traced this quintessential American family story in her acclaimed history “The Black Calhouns.”)

Jenny Lumet is unabashed about her great-grandfather. He was handsome, sharply dressed, a gentleman, and “a gangster.” By the time he set foot in that studio lot, Teddy Horne had befriended and/or partnered with some of America’s most infamous men, including Jewish mobster Dutch Schultz and Harlem strongman Bub Hewlett. Teddy’s outsize presence and connections altered the usual balance of power in the room. Horne laid down the law, telling Louis B. Mayer that his daughter was going to get a competitive wage and she wasn’t to play the subservient roles other Black actors had done. As film historian Donald Bogle has since reported, Horne told the white executive, “I can buy my own daughter her own maid.”

The sentiment was controversial and perhaps condescending to the men and women who did that work and played those roles. But Teddy Horne was representing more than his daughter and their family in that meeting. He was pushing existing boundaries.

In Practice, and Sometimes in Law, Hollywood Was Segregated

As both the Nicholas family and the Hornes saw, in the ’30s and ’40s, even Black nobility wasn’t welcome outside of the movie sound stage. Initially at least, Lena did not want to be in Hollywood. She had the support of the NAACP and special treatment from the studios, but off the set and after hours, she still had to contend with the de facto segregation that prevailed (and sometimes de jure as well when it came to housing).

Los Angeles wasn’t the Jim Crow South, but discriminatory covenants restricted who could buy homes in many neighborhoods. When Lena came west, a house had to be lent to her. Housing struggles persisted for years. In 1947, when Lena returned from Paris married to composer and conductor Lennie Hayton, their white neighbors objected to the interracial couple’s presence on their leafy white suburban street. As Jenny Lumet learned from her family, Humphrey Bogart, who lived nearby, responded with his own brand of pressure, going door to door “with a gun in his belt,”and instructing those white residents that Lena and Lennie were not moving and were not to be bothered. “If Lena and Lennie don’t get their newspaper in the morning, I’m gonna come see you,” he reportedly said.

Lumet calls Bogart, “a hero” and said that a couple others were heroic as well. But she also points out that this didn’t diminish the daily challenges Horne faced: “you’re on the set, doing the thing and the minute you leave, you are no longer an asset. You’re just a Negro taking up space. … No one was safe once they left the set.”

“You Have to Go Back”

Being a symbol for change is never an easy role, and it took a toll on Horne. As Lumet shared, for Horne’s family, the pride and memories of this time are often intertwined with pain. One feeling that is evoked is isolation. At the outset, in Los Angeles, MGM tried to keep Lena away from other Black people. The East Coast had been her home. It’s where her family and friends were. The West Coast was far away and, plainly, in some ways the experience was “horrible.”

Paraphrasing the story she’s been told (and one that has also been backed up by film historian Bogle), Lumet said that a group of activists and Black performers told Lena Horne that she had to stay in Hollywood. In essence what legendary performer and activist Paul Robeson (a close family friend and mentor) told her was: “You have to go back because they picked you and they never pick us. You have to go back to break the unions. You have to go back on behalf of the Urban League, and you have to go back because Nazis are making inroads in America, and you have to go back for all Black people.”

And yet, in doing so, in the short term, Lena’s unique position put her at odds with Black Hollywood. There was a feeling that she made things harder for Black performers making their living playing the servant roles the NAACP and the Horne family demanded that Lena Horne shun. In the 1930s and 1940s by choice or necessity, Black performers often lived and socialized together. But Black artists’ views on how to deal with the constraints of the industry weren’t uniform: Black performers disagreed over what roles to take, how much to conform and how much to push against those constraints.

Some feared losing work. Taking stereotypical roles paid. And sometimes playing a stereotype was the only opportunity in town, so performers made do and tried, when possible, to also imbue restrictive roles with humanity. Others, like Paul Robeson, repeatedly rejected the status quo, speaking out openly against injustice, and eventually paid a high price, not just in being blacklisted by Hollywood studios but also in having his passport revoked by the U.S. State Department for a decade.

In 1942 though, there was unease among some members of Black Hollywood when the NAACP started advocating for change and when Lena became the symbol of that shifting landscape. There was palpable resentment. There was gossip. There was even another meeting in which Black performers applied pressure to Horne to go along with the way things had always been. As Lumet recalls, “she was sort of sat down and called to the carpet by about 10 Black actors who said ‘If you’re not going to play maids, what are we supposed to do?’”

Ironically, when Horne was becoming persona non grata among Black performers, it was Hattie McDaniel, the actor who won an Oscar in 1940 for playing the stereotypical role of “Mammy” in “Gone With the Wind”, who stepped in.

Hattie McDaniel wielded influence within her community. And she used that, according to Lumet, to come to Horne’s rescue. Horne stayed and made two watershed Black cast films in 1943, “Cabin in the Sky” for MGM, and “Stormy Weather” for 20th Century Fox. These films also serve as a warning: They are a glimpse of a momentary Hollywood breakthrough. But after World War II ended, the desire to include Black artists on screen in meatier roles faded, and you wouldn’t have studio films with an all-Black cast for another decade. It’s a reminder that any progress — including the progress the industry has made today — needs to be carefully guarded.

READ MORE: 15 Essential Black Performers of the Golden Age

Launch Gallery: 15 Path-Breaking Black Performers of Old Hollywood — and Early American Indie Film

Best of IndieWire

Christopher Nolan Movies, Ranked from 'The Dark Knight' and 'Tenet' to 'Dunkirk' and 'Oppenheimer'

Where to Watch This Week's New Movies, Including 'Argylle' and 'How to Have Sex'

Christopher Nolan's Favorite Movies: 40 Films the Director Wants You to See

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.