Blinding speed and unbearable intensity: How King Crimson got started

It’s mid-August, 1969. The apocalyptic blast of 21st Century Schizoid Man is abruptly cut off in mid-flow as engineer Robin Thompson mutes the speakers in the London studio where it is being recorded.

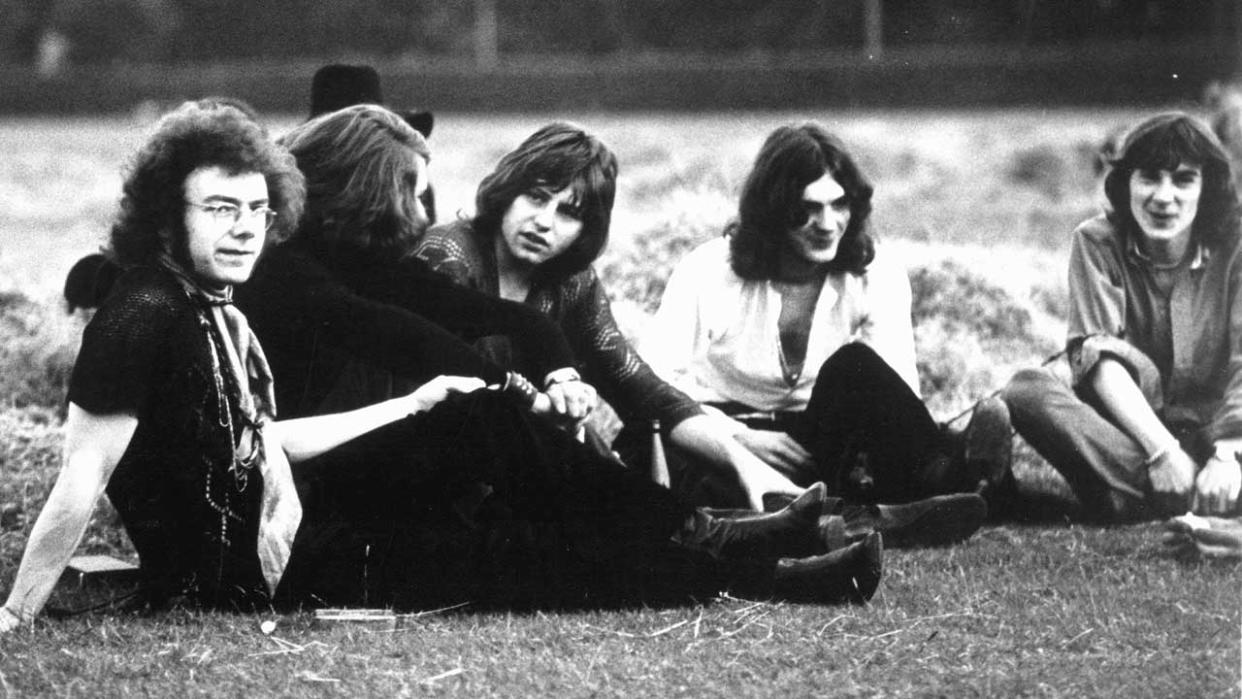

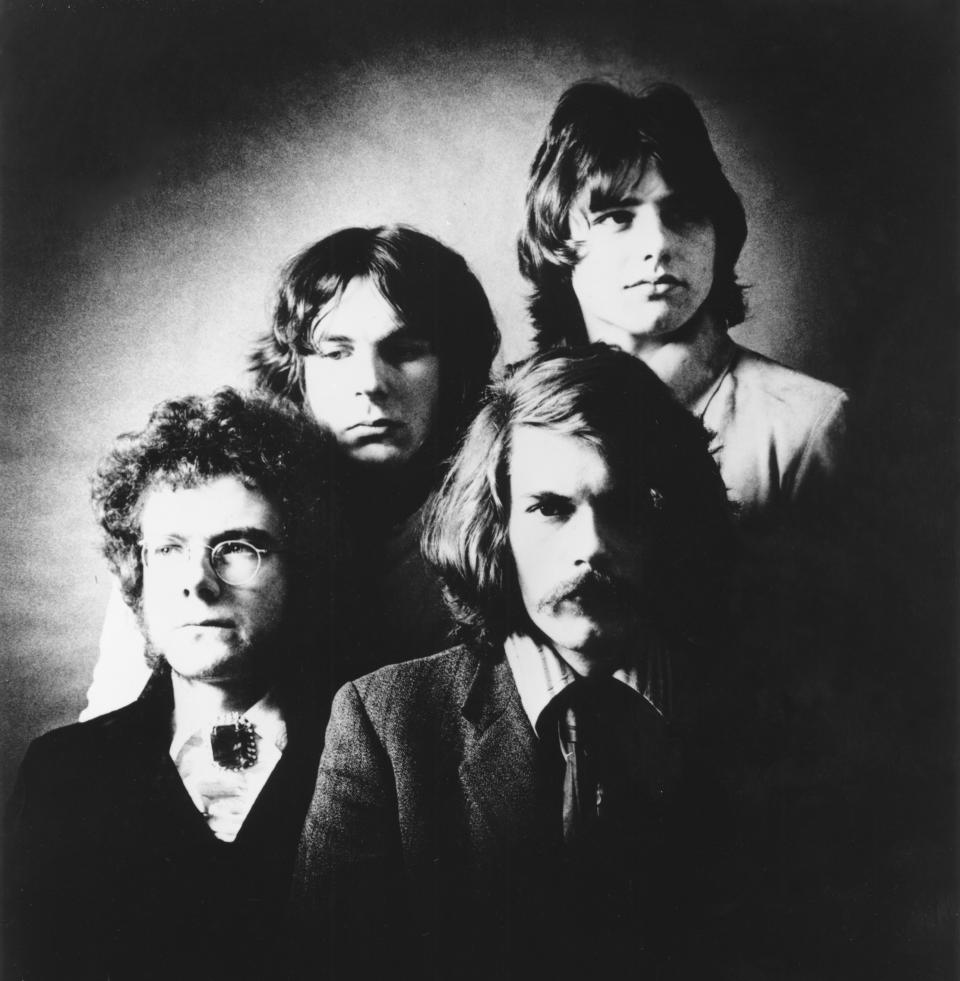

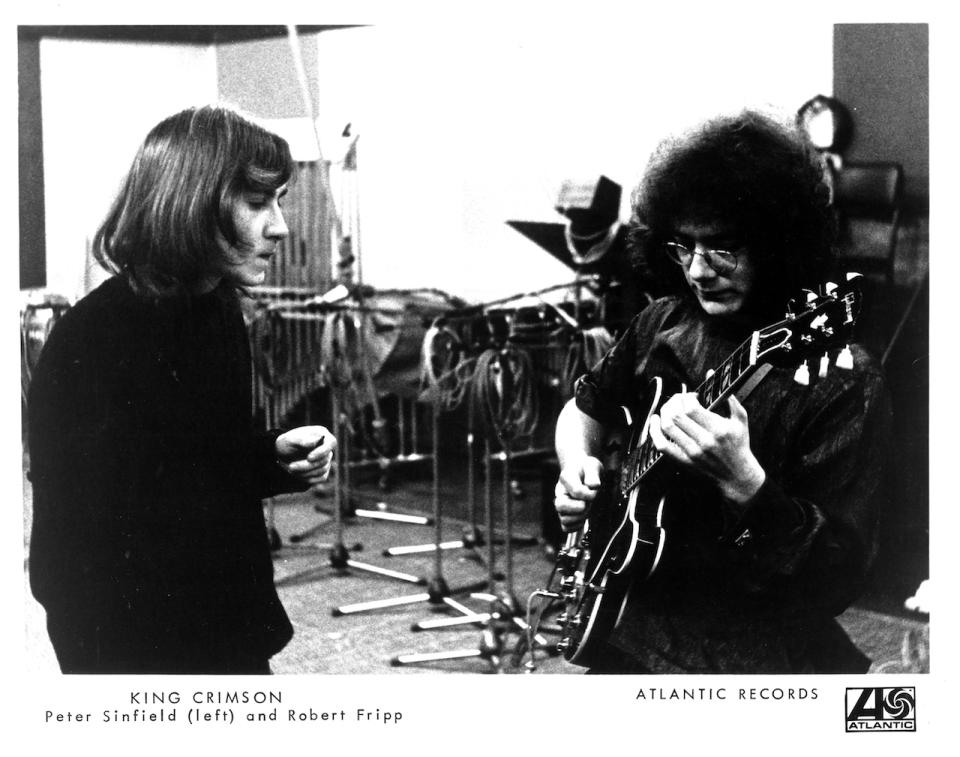

Gathered in the cavernous performance area of Wessex Studios, where their band King Crimson are recording, Robert Fripp, Michael Giles, Ian McDonald, Peter Sinfield and Greg Lake stop work to welcome the arrival of artist Barry Godber, who is carrying a large rectangular package wrapped in brown paper.

A few weeks previously, Sinfield had commissioned his friend Godber to come up with something for the cover for what would be King Crimson’s debut album.

“I used to hang around with all these painters and artists from Chelsea Art School,” says Sinfield, recalling the event 40 years later. “I’d known Barry for a couple of years. He’d been to a few rehearsals, and spent a bit of time with us. I told him to see what he could come up with. I think I probably said to him that the one thing the cover had to do was stand out in record shops.”

Godber tore off the brown paper and laid the painting on the floor as the band gathered around to see his handiwork.

“We all stood around it,” says Greg Lake, “and it was like something out of Treasure Island where you’re all standing around a box of jewels and treasure… This fucking face screamed up from the floor, and what it said to us was ‘schizoid man’ – the very track we’d been working on. It was as if there was something magic going on.”

Magic and King Crimson never seemed to be far apart during 1969. Even before they had played a proper gig there was an expectant buzz doing the rounds about the monstrous sounds emanating from the band’s rehearsal room in the cellar of a café on Fulham Palace Road in west London.

Exactly one month after their first proper rehearsal, on January 13, Decca Records A&R man Hugh Mendl, having been persuaded by Crimson’s managers David Enthoven and John Gaydon to sample the band, arrived at the rehearsal room with Moody Blues producer Tony Clarke, with a view to having Crimson sign up to the Moodys’ own Threshold label.

“We had taken various people down to see them, and everybody who saw them was blown away by them, apart from Muff Winwood, who was then A&R at Island,” Enthoven remembers. “I’ll never forget that he turned to me and said: ‘They’re a bit like the Tremeloes, aren’t they?’ I thought to myself: ‘What the fuck are you listening to?’”

While many bands were cranking up the volume, as the burgeoning ‘underground’ scene demanded, what distinguished King Crimson from most of their contemporaries was their lethal combination of claw-hammer brutality and surgical precision. They were summoning up musical forces not only possessing immense subtlety but also with the power to drive punters into the ground like tent pegs. It was this impressive combination that turned heads and got the word-of-mouth bush telegraph buzzing.

Almost every band starting out has a wish-list of hopes and dreams – getting good; getting in print; getting on John Peel’s radio show, getting big, getting signed; getting an album in the Top 10. In just 1969 King Crimson got the lot. Even now, looking at it from 40 years’ distance, the speed of their progress is breathtaking.

In April they played their first London gig, at The Speakeasy, to great acclaim. In May they recorded a session for John Peel. That same month, Jimi Hendrix saw them play at another hip London club, Revolution. Shaking guitarist Fripp’s hand, Hendrix declared excitedly to anyone who would listen that Crimson were the best group in the world.

With that endorsement still ringing in their ears, in June the band arrived at Morgan Studios with best-selling producer Tony Clarke to begin recording their first album.

International Times – the counter-culture ‘house magazine’ – interviewed the group at the start of recording, and it was evident that the mood in the Crimson camp was understandably upbeat. Fripp talks about doing a double album with one side per track; Sinfield wants to ensure that everything – music and album cover – is integrated as a total package.

The band had gone from complete zeroes to would-be heroes with a cocky master-plan, a double-page spread in the press, a growing reputation for killer concerts, and an album in the works. Not bad going in just six months.

Yet the sessions between June 12 and 18 didn’t go quite as smoothly as expected. Something about the sound at Morgan wasn’t working for them. As they relocated to the more spacious Wessex Studios, the band prepared for the gig that would seriously accelerate an already fast-track career – supporting The Rolling Stones at Hyde Park on July 5.

“Right from the off we knew that the Hyde Park show was absolutely important,” says David Enthoven. “It was going to be a huge gathering of people and a great opportunity for the band to play to that kind of crowd… and we were trying every means possible to bribe and corrupt dear Pete Jenner [of the event’s organisers, Blackhill Enterprises]. I was happy to give him quite a lot of money. They wouldn’t take the money, but they put us on the bill because of the sheer brazenness of us. I would’ve done anything to get on that bill.”

King Crimson stepped out onto the Hyde Park stage and faced an estimated audience of 650,000 – a nerve-racking experience for anyone, as bassist/vocalist Greg Lake remembers vividly: “I’d never seen that many people in my life – for any reason. I mean, you’d need a war to see that many people! They weren’t there to see me or King Crimson, they were there to see The Rolling Stones, so in a way it wasn’t that bad.

“All of a sudden we play …Schizoid Man at blinding speed and unbearable intensity,” Lake continues. “Suddenly everyone starts to take notice and stand up. Then we started playing the beautiful stuff, like In The Court Of The Crimson King and Epitaph. Well, by then it was game, set and match. It worked very well. I realised it was a turning point the moment I walked off stage, because you can’t go down that well at an event that big and it not be significant.”

Returning to Wessex Studios on July 7, Crimson and producer Tony Clarke had a second attempt to record the album. Almost immediately more doubts about the sounds they were getting resurfaced. Maybe it wasn’t the studio that was the problem. Maybe it was the producer. Clarke’s preferred way of working – slowly building up big backing tracks as he’d done with the Moody Blues – wasn’t suiting Crimson’s dash for dynamics and cocky, live-take bravura.

Drummer Michael Giles felt Clarke was trying to tame Crimson’s energies and shape the band into something they were not. Lake agrees: “The general sense we had was that his main motivation was to make us another version of the Moody Blues, and we didn’t want that.”

On July 16 they decided to walk away from Clarke and also the prospect of a Threshold label release that came with him.

It seems almost inconceivable that a young band who had only been together just over six months would take such a risk at such a pivotal point in their career. Another example of Crimson’s so-called ‘Good Fairy’ that they talked about looking after them, or testosterone-fuelled balls of steel?

“You’ve got to remember that all the people in King Crimson were very strong personalities,” Greg Lake explains. “They were very intelligent, very good musicians and all opinionated – not in a nasty way, but everyone was passionate about what they were doing. All very dedicated and all of us out to change the world in one way or another. The fact of the matter is that when it came to music making and the music we were making, really Tony didn’t know enough about it. We felt that we could make a better job of producing the record, because we knew more about it than he did.”

In order to finance the self-produced album, managers Enthoven and Gaydon swung a deal with the Thompson family (Wessex Studios’ owners) that guaranteed the £15,000 recording costs. To do this, Enthoven remortgaged his house. “A bit of punt, really,” he says. “It was either a test of commitment or bloody madness on my part! We knew it was going to be successful, so at the end of the day it was just down to money, and we had to find the money to do it.”

On Monday, July 21, 1969, as man first walked on the Moon, King Crimson walked into Wessex Studios, took control of their own fate and began work on their elusive debut album for the third time.

Over the next fortnight, in-between gigs, they spent three days laying down backing tracks for In The Court Of The Crimson King, one day apiece on I Talk To The Wind and Epitaph, a day on Moonchild and its improvised instrumental work-out, and, finally, Crimson’s magnum opus, 21st Century Schizoid Man, completed in just one, devastating, live take.

August was spent mixing the original eight-track tapes down to two in order to do extensive overdubs. Peter Sinfield recalls their no-nonsense approach to the task: “We weren’t one of those bands who rolled a couple of joints and had a Scotch before we started work at midnight, we used to get up there at lunchtime and work through until we were exhausted at around nine or 10 and not push it. We worked fairly hard and we did it very quickly. We could do it very quickly because everyone knew their parts very well, because we’d rehearsed it and played it, which helped a lot.”

The album’s final overdub – Robert Fripp’s one-take guitar solo for …Schizoid Man – was completed on August 20, with plans already under way for the finished album to be leased on Chris Blackwell’s Island Records label.

If the band and their fans (including Pete Townshend, who famously dubbed the album “an uncanny masterpiece”) thought things had been moving fast for Crimson prior to its recording, the whole adventure went into hyper-speed when the album was released in the UK in early October.

Going straight into the top five of the UK chart, the potent, ground-breaking music, with its iconic album sleeve – one of the first not to have a band name or record company logo on its gatefold front – demanded to be heard.

“Not having the name on the front cover meant that if you were fingering through the racks in the record shop and you came across it, you had to open it up to see who it was,” says Peter Sinfield. “You were being led further into our world. Hopefully then you’d want to hear it, and then buy it. It was exactly done that way. I remember being in Oxford Street just after it was released, and seeing a whole shop window full of them. I thought: ‘Strewth, what have we done?”’

The band had been together less than nine months at this point.

Running like the soundtrack to some epic, unreleased movie, the album was a decisive break with the blues-rock motifs that still dominated much of the underground scene’s output. There are no lengthy solos anywhere on the album. Instead their collective firepower is directed into beautifully crafted and detailed arrangements, symphonic allusions and a precocious ambition in a group so young.

The unrelenting pace of Crimson’s life on the road began to take its toll once the band arrived in the USA as the album entered the Top 20 there. In the midst of a kaleidoscopic American travelogue that covered the vast coast to coast distances, Michael Giles and Ian McDonald, homesick, lovesick and beginning to find the hectic pace more than they could handle, both decided to quit the band at the end of the tour.

When Crimson left the stage of San Francisco’s Fillmore West on Sunday, December 14 it was over. The whirlwind of 1969 had seen them play more than 70 gigs and get one album out in a mere 335 days from start to finish.

Though King Crimson would continue with different line-ups over the ensuing years, the one now iconic album by the original, short-lived group has become a touchstone and a defining moment in rock’s development.

Greg Lake: “It fired the starting pistol on progressive rock… I think there were other bands that you could also credit with bringing about a new attitude in music: Pink Floyd were one band that brought new stuff along. So I wouldn’t say Crimson were the only band to bring new things along, but we were certainly fundamental and important in the progressive movement. The album provoked a lot of changes.”

Peter Sinfield: “You don’t think about the legacy of an album as you’re doing it, but I have learnt – just by being around long enough – that it’s the greatest feeling in the world to have done something like that. To have written something that lasts and has a bit of a timeless feel to it. We didn’t philosophise about it at the time because we didn’t have time all those years ago. But here it is 40 years later, better than ever."