'The Blues Society': The story behind the new documentary about Memphis Blues Festivals

On July 21, 1966, the Ku Klux Klan held a rally in Overton Park. The chief speaker was Imperial Wizard Robert M. Shelton of Tuscaloosa, Alabama, who "told the crowd of about 400 Klansmen, supporters and curious onlookers to work for ‘conservative candidates’ in the coming elections,” according to the evening newspaper, the Memphis Press-Scimitar.

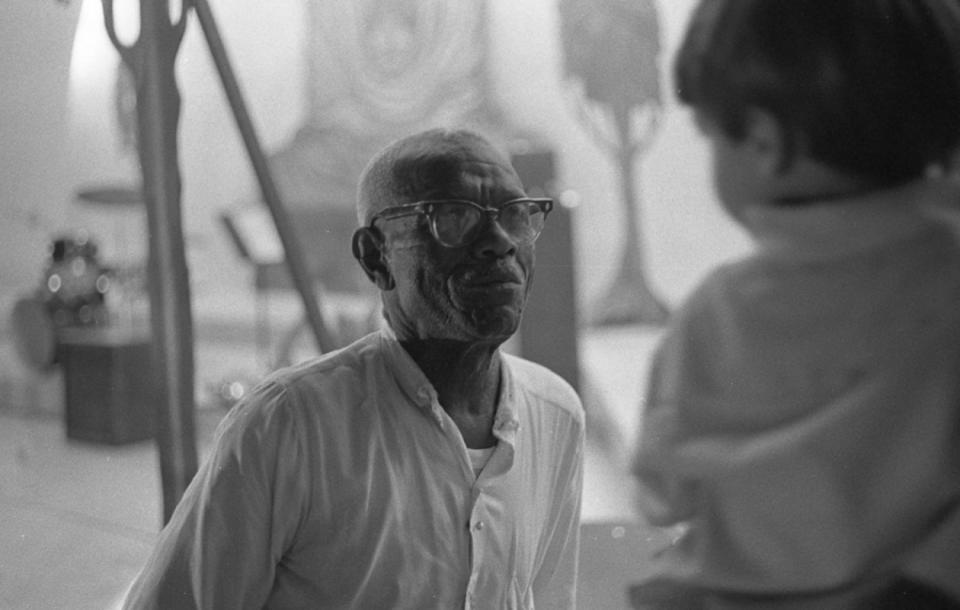

A little over a week later, on July 30, the vibe was entirely different as “all the freaks in town” gathered in Overton Park for the first Memphis Blues Festival, a celebration of Black musical expression that was organized by young white music lovers and that showcased such elder giants-in-our-midst as Furry Lewis, Rev. Robert Wilkins and “Mississippi” Fred McDowell.

As a Press-Scimitar headline about these so-called rediscovered artists explained a year later, in a paraphrase of a quote from Nesbit, Mississippi, musician Joe Callicott: “The Blues Ain’t Been Lost, Man — They Been Right Here.”

What was lost, for decades, was footage of any of the five Memphis Blues Festivals held at the Overton Park Shell from 1966 to 1970.

Also essentially missing was any serious reckoning with the racial, cultural and artistic significance of these mostly pre-Woodstock events, which eventually attracted national attention even as they remained rooted in the music of Memphis and the Delta, with lineups that included Gus Cannon, the Bar-Kays and Rufus Thomas.

A new feature documentary from director Augusta Palmer, “The Blues Society” digs deep into the fertile musical soil, cultural clay and, yes, literal hash — “a lump of hash the size of a softball” was a prime motivator, according to musician Jim Dickinson — from which the festivals sprouted.

Rich with rediscovered footage, the movie — which bills itself in an onscreen caption as "a Moving Image Mixtape" — will have its world premiere at 3 p.m. Sunday at Playhouse on the Square, on the closing day of the six-day Indie Memphis Film Festival. Palmer and other participants in the documentary will participate in a post-screening question-and-answer session, and a "Country Blues Fest Revival Concert" is set for 6 p.m. the same night at Minglewood Hall.

Palmer — whose father, the late music critic Robert Palmer, was an organizer of the blues festivals — said she has been working on her film "in earnest" for close to seven years. However, "Sometimes I Iike to joke that I've been making this movie all my life," she said, noting that her mother, whose voice is heard in the film in a recording made at the 1969 festival, was pregnant with her at the time.

Constructed by Palmer, Memphis editor Laura Jean Hocking and other collaborators from vintage and new material, "The Blues Society" may remind viewers of Questlove's "Summer of Soul," about the Harlem music festivals of the late 1960s, which last year won an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. But if the Harlem concerts pointed toward an unrealized Black cultural Utopia, the Memphis events were more fraught. "The Blues Society" pays tribute to the progressive and sincere enthusiasms of the festival organizers, but it also acknowledges the “paternalism” inherent to the racial “power dynamic” that separated much of the production team and audience from many of the performers.

The film also grapples with the legacy of the events, which set the stage for the Memphis in May Beale Street Music Festival and other attempts to capitalize on an art form that largely was born from what Palmer calls "pain and hurt and really hard lives," however joyous its expression and tourist-friendly its framing.

Whatever caveats accompany reminiscences of the festivals, "There was a camaraderie and a humanity that got shared that was above and beyond the ordinary," remembers Memphis musician Jimmy Crosthwait, in the film. "It was transcendental, in a sense."

MEMPHIS MUSIC ICONS: Meet the titans and pioneers of the blues, the city's defining genre

The Memphis Blues Festival (sometimes billed as the Memphis Country Blues Festival) initially was organized by a loose coalition of blues devotees and proto-hippies from Memphis, Little Rock and New York. These allies were gripped by what the late Memphis art-inciter Randall Lyon describes in the film as eroico furore: "We had poetic fury." "We want to preserve these musical forms so that the ‘Memphis sound’ will still live," the festival organizers wrote, in a mission statement.

Drawing shaved-head military enlistees as well as what Robert Palmer called "all the freaks in town" to see musicians who in some cases had been forgotten since their 1920s recordings, the events weren't highly profitable but were successful enough to earn favorable local and eventually national coverage from Rolling Stone magazine, New York public television station WNET and former "Tonight Show" host Steve Allen. But the festivals seemed to be more or less forgotten until Memphis writer/historian Robert Gordon devoted a chapter of his seminal music history book "It Came from Memphis" to the events.

Augusta Palmer, 53, first became interested in the festivals because of the involvement of her father and her mother, Mary Branton. Her documentary might not have been possible, however, if Maryland blues archivist Gene Rosenthal hadn't held onto some 17 hours of footage and 33 hours of audiotape from the 1969 festival, which he and a crew had shot for WNET.

Stored and forgotten in Rosenthal's basement, the footage first was exhumed for a 2019 documentary, Los Angeles director Joe LaMattina's "Memphis '69," produced for Fat Possum Records (and available for free on the label's YouTube channel). An almost fly-on-the-wall (weevil-in-the-park?) concert film, "Memphis '69" functions as a complement to Palmer's film, which provides history and context the other movie lacks.

"I was always a little more interested in the idea of a film that was about the time, and understanding what went on," said Palmer, whose previous movies include "The Hand of Fatima," a 2009 documentary centered on Morocco's Master Musicians of Joujouka, a Sufi trance band.

Born in Little Rock, Palmer has lived in Memphis on occasion (she attended Rhodes College for a year), but has mostly been based in New York. She earned a Ph.D. from New York University for a dissertation on 1990s Chinese cinema; now, she is a professor of filmmaking and media studies at St. Francis College in Brooklyn.

MEMPHIS MUSIC HISTORY: From Elvis to B.B. King, take a Memphis music history tour with stops at these statues

As a result of this geography, the experience of making "The Blues Society" echoed that of the festivals' original curators, as Palmer traveled back and forth from Brooklyn to Memphis to investigate the blues, with the help of people who were at the festival as well as younger cultural critics and scholars.

She also corralled footage from past interviews with folks who had passed away, such as Lyon and Dickinson. Said Palmer: "Things were hectic and there were a lot of drugs done, so I'm surprised anybody remembered anything."

Among the younger people who appear in "The Blues Society" are sociologist Zandria Robinson, who addresses the "power dynamic" that accompanies "cross-racial" collaborations, and writer Jamey Hatley, who questions why she used to feel "a little embarrassed" by the blues ("Me hating the blues is like a fish hating water"). Meanwhile, white blues acolyte Zeke Johnson acknowledges there was a "paternalistic" element to the white embrace of certain ancient-seeming and uneducated country blues artists.

Overall, however, the message is pro-Memphis, at least in its role as a crucible of art. As Memphis Blues Festival attendee John Larkin says in the movie: "All the hell Memphis has done is taught people how to talk, dance and play music — and we still do that."

'The Blues Society' at the Indie Memphis Film Festival

World premiere of "The Blues Society" — 3 p.m. Sunday, Playhouse on the Square, 60 Cooper. Director Augusta Palmer and others will participate in a post-film Q&A. Tickets: $12. (The movie also can be screened online Oct. 24-29 by those who purchase access to the "virtual" festival.)

"Country Blues Fest Revival Concert" — doors open at 5 p.m, show starts at 6, 1555 Minglewood Hall. Carrying on in the traditions of their Mississippi musical forebearers, Sharde Thomas (granddaughter of fife master Othar Turner) and her Rising Stars fife-and-drum band will perform, along with the Wilkins Sisters (daughters of Rev. John Wilkins). Tickets: $33.55, or free to festival passholders.

For passes, tickets to other events, and a full Indie Memphis schedule, visit indiememphis.org.

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: 'The Blues Society' chronicles Memphis Blues Festivals of the 1960s