In New Book, Johnny Marr Lets His Guitars Tell His Story

More from Spin:

Pretenders Welcome Johnny Marr, Dave Grohl During Glastonbury Festival Set

Former Smiths Bandmates Morrissey, Johnny Marr, Mike Joyce Salute Andy Rourke

Andy Rourke, Bassist For The Smiths And Morrissey, Dies At 59

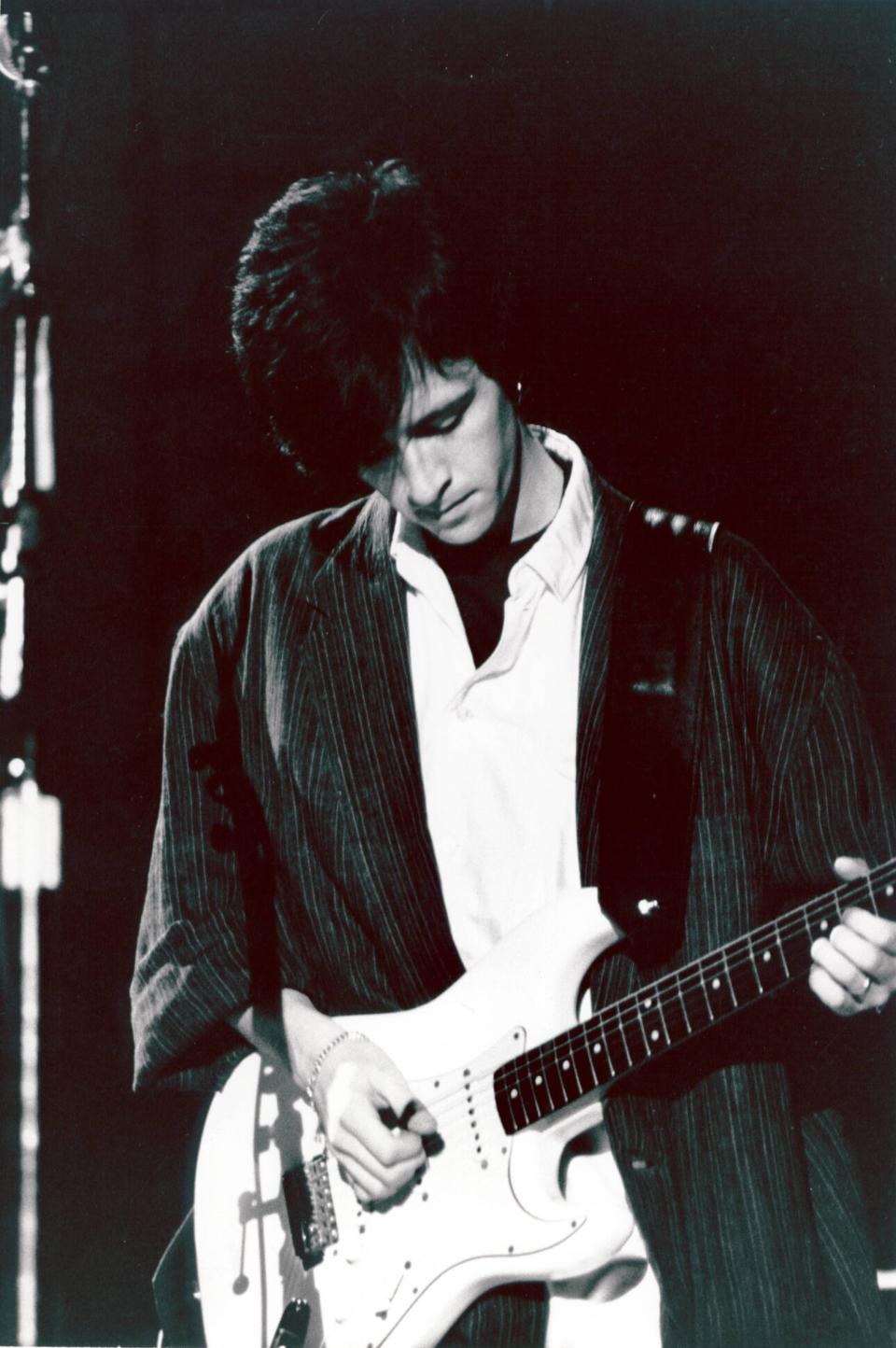

A coffee table book of stunning guitar photographs from Johnny Marr’s collection is long overdue. Marr’s Guitars arrives four decades after the release of the first Smiths single and tells the story of Marr’s life through his guitars.

The book moves chronologically, illustrating Marr’s experiences with artistically-shot images of his guitars positioned against amps, walls, and carpets by photographer Pat Graham. There are closeups showing the wood grain and the wear and tear, adding even more character to these beautiful instruments that carry so much history. Each photograph has brief details about the instrument and the songs on which it was used. As Marr says in the book, “I had a rule that if I bought a guitar, I would have to write a song on it to justify the expense.”

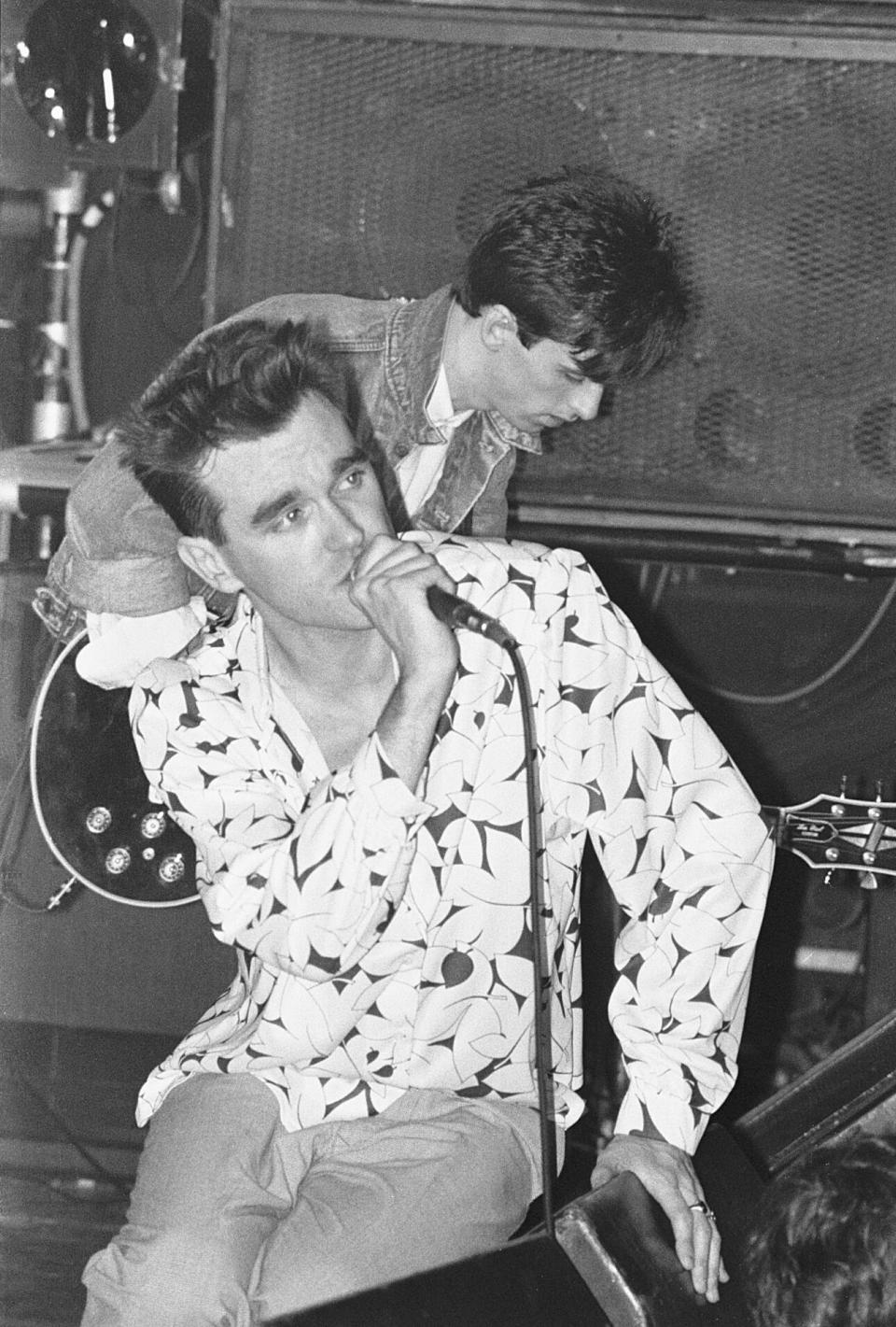

Complementing the guitar pictures are classic photographs of Marr himself. Some of these are familiar, many of them are not. There are also images of other musicians to whom Marr has famously given or lent his guitars, including Noel Gallagher, Ed O’Brien, and Bernard Butler. They share stories about their use of Marr’s instruments, further contextualizing Marr’s story.

In three sections, Marr himself is interviewed. His responses are not a rehash of his well-received 2016 autobiography, Set the Boy Free. Rather, they offer a different perspective on Marr’s experiences through the lens of his guitars. Marr’s Guitars has an unexpected emotional impact, which caught Marr by surprise, as he told The Guardian, the book stirred the kind of feelings he was expecting when he was writing Set the Boy Free, but which never came.

Marr’s Guitars is a book for Marr fans, for Smiths fans, for fans of guitars, but also for appreciators of art and photography. It’s made even more special with the involvement of Marr’s daughter, Sonny, who is in publishing, lending her expertise, and his son, musician Nile Marr, choosing the cover image of a young Marr with a cigarette hanging from his mouth. Says Marr, “If you’ve got smart kids, they get to a certain age, they’re not going to kiss your ass. Nile said, ‘Fans are going to want that photograph.’”

Marr is making a few appearances over the next month leading up to his landmark shows this December in his hometown of Manchester, UK. In addition to in-store signings and Q&A sessions around the UK in support of Marr’s Guitars and his upcoming greatest hits compilation, Spirit Power: The Best of Johnny Marr, Marr is hitting Brooklyn and Los Angeles for in-conversation events.

Ahead of these events, Marr sits down with us to do a some mental calculation about the 132 guitars he says he owns in Marr’s Guitars, determining that since wrapping the book, he might have a few less – and that he should develop an app to keep track of which ones he has out on loan.

How did the idea of Marr’s Guitars come about?

It started off a little bit upside down. My original vision was a book of abstract, beautiful Pat Graham photographs that used my guitars as the source material. A great coffee-table book of super close-up, dirty, rusty, scratched-up, almost industrial textures of my guitars and my equipment.

The next consideration I had was that, as a boy, my more middle-class friends’ houses had coffee table books in them. I used to love poring over these books, because we didn’t have those in my house. My house had rock ‘n roll records. It occurred to me that a beautiful coffee table [book] that people who would otherwise not have guitar books in their house would be a great idea.

I talked my good friend and art director Mat Bancroft into the idea, got him on board, which [meant it was] going to happen. Once I got the title, Marr’s Guitars, it was a no brainer. In the process of putting it together, it became obvious we needed straight pictures of the guitars. They were more difficult to do because of reflections and lighting and the colors of the guitars not being wrong because of lighting and reproduction.

The text of my stories and talking about playing with R.E.M. or recording Strangeways… or recording Pet Shop Boys, or New Order using my guitar on “Regret,” and Radiohead’s Ed O’Brien’s contribution, all of that came as a fourth or fifth thing down the line. The big thing that happened in the process was me remembering all these stories of what I used all these guitars on. I thought, “I’ll just mention I wrote “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now” on that guitar, and, “That’s the guitar I got from Nile Rodgers.” It became very in-depth. It’s become this very detailed visual reflection on what I’ve been getting up to, in and out of the studio, for 40 odd years. It’s the story of 1980 ‘till now. It’s also become very personal. This book has become quite a big thing in my life.

Without the written narrative, it would still be a beautiful book, but with those parts, it’s something else entirely with an added emotional pull.

Not being for guitar nerds, I wanted my conversation in the book to read like someone was sat on the sofa with the book next to me and asking, “What’s this about? Why did you use this? You had a job in a guitar shop as a kid? Tell me about that.” As a teenager, I guess Americans call it playing hooky, is that right? I used to go to my friends’ houses quite a lot. We used to have this very elaborate network. We had a matrix of houses where our mothers were out working. We’d go to one house on Wednesday afternoon and Tuesday morning we came to my house, to listen to records. As I said, I used to pore through those books. I have that associative memory of sitting on the couch and I wanted the reader to be sat next to me feeling like they were asking me the questions.

Your recall is astonishing.

I was also the producer, and I was writing the guitars down on the track sheets, particularly in the ‘90s. Because I owned the studio, I used to like writing that stuff down. It was part of my education, if it’s not too pretentious a word, my evolution to become a proper record producer.

Near the end of the book, I was going to bed really late one night, having worked on the book all day. As I was going to bed, I thought, “Hang on a minute, didn’t Bernard [Sumner] use the red Les Paul for ‘Regret’?” I WhatsApped him and he came back the next day and said, “Yeah, I did.” When he was in the studio at Real World working on that New Order record, we were on the phone, he said, “I used your red Les Paul,” and I remembered it. I’m so close to my guitars I remember those things. They’re important to me.

You have given and lent guitars over and over again, but nobody gave you one, at least not when you were starting out.

Guitars were much rarer, more valuable, expensive and exclusive back then. I did know of every guitar that was within the 10-mile radius of my house, maybe even wider. I could reel off a lot of the names of the people—nearly always older than me and nearly always guys back then—even now. As I say in the book, on occasion I turned up at their house to see their guitars. Because I was so young, they indulged me. That’s how much of a rarity those things were and how obsessive I was. But no one was going to give me one, absolutely not. The closest I got to that was Billy Duffy selling me his little practice amp for £15. He put his pink punk-rock shirt in the back of it, which was very sweet, because I used to really hassle him about his shirts. The most I got out of it was a shirt, but I had to pay £15 pounds for it. It’s a good shirt though.

How did you decide which amps to position the guitars up against for the photographs?

It was 100% [an] aesthetic decision in the moment. There was some pushback from my tech Rich, who is very academic about these things. He would say, “That’s a ‘60s amp and you’ve got this ‘50s guitar in front of it.” I would say, “I know, but the brown goes really well with the Tolex.” I’ve got many more amps and some of them are quite famous Smiths ones, but one of the many things I don’t like about all guitar books is you get information overload. I didn’t want to pack the book full of too many bits of gear. There’s not a ton of pedals in there, just my Smiths pedal board.

Having that one pedalboard makes it that much more special.

There’s a closeup from the TEAC tape machine that I recorded all those early Smiths songs on. The Smiths artifacts, I understand, have great interest because of the band’s legacy and because it’s the oldest and the ‘80s are fashionable and all of those things, but I think I got the balance right. Off the top of my head, the Smiths items are maybe 35% of the book. I’m really glad that didn’t tip over too much. I would have forgotten that I played with REM every night on a tour.

What are you going to do with a picture of a Rickenbacker double neck, which is unusual in itself? Put me and Peter Buck underneath it of course. Those three beautiful pages came about right near the end of the book. I was running and I just remembered that picture and my daughter chased it down. The photograph of the Rickenbacker with the real close up of the two knobs and the photograph of me with the mirror shades from 1985 opposite, some people have said to me, “Is that intentional?” Fuck yeah, it’s intentional. Those artistic creative moments are really fun.

The anecdote you share about making Sire Records’ president Seymour Stein buy you a guitar when/if The Smiths signed with him is priceless.

When I’m done with this book, it’ll be good to not have to tell that story again. But I know it’s a good story. Seymour really loved that story. Every four or five years or so when I was in New York, I’d get an email from him and I’d nip over to see him. I did see him shortly before he passed away. He would make a point of getting me to tell whoever was in the room that story. It wasn’t a cheap guitar, even back then, but I think he got his money back. Little things like that are why I went out of my way to sign my solo albums to Sire.

The process of creating the book sounds incredibly involved.

The two books I’ve done have been quite involved. I can’t leave it up to other people. Everything I get into, I have to really follow through to the nth degree. The autobiography was nine months of writing, which actually is pretty quick, but I was pretty wiped out mentally after doing it. Albums are like that with me. If I get a concept or an idea that I realize is a big one, I don’t just do it on a whim because I know it’s going to take over my life and my family’s life for the next couple of years. I feel like I’m still swimming in the whole process of the book. It wasn’t just a musician vanity project. It’s been a mission. I’m still dreaming about different guitar cases.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.