‘The Boy and the Heron’: How GKIDS Pulled Off One of the Most Important Dubs in Anime History

Founded in 2008, New York-based production studio and distributor GKIDS almost immediately established itself as the United States’ most valuable lifeline to animated cinema from around the world, and so — after earning 12 Oscar nominations for introducing modern classics like “The Tale of the Princess Kaguya” and “Wolfwalkers” to American audiences — it might seem a bit overblown to suggest that the label’s reputation could still hang in the balance of a single dub. GKIDS president Dave Jesteadt certainly didn’t expect that to be the case when he formally took the reins in January 2017, as the already thriving company was still on the verge of its greatest triumphs. And yet, by the end of the following month, everything that GKIDS had accomplished would seem like a long prologue for the challenge that would ultimately define it.

On February 24, 2017, Studio Ghibli co-founder Toshio Suzuki announced that legendary filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki was coming out of his latest retirement to make another “last” film (his first since 2012’s “The Wind Rises,” which Disney handled in the West), and by that point — after successfully partnering with Ghibli on minor releases such as “From Up on Poppy Hill” and “When Marnie Was There” — it was a foregone conclusion that GKIDS would eventually be responsible for its North American release. It was likewise a foregone conclusion that it would be the biggest and most important and high-profile project in the brief history of a company that had treated all of its films with the respect worthy of a titan’s farewell.

More from IndieWire

If done well, the dub would cement GKIDS’ importance to the animation industry, and invite a wider portion of the English-speaking world to surrender themselves to a surreal but summative masterpiece by the greatest animator the movies have ever known. If done poorly — if it betrayed even a hint of the awkwardness that crept into several of the sensitive but stilted dubs that Disney commissioned during the John Lasseter years — it’s possible that nothing GKIDS ever did would be enough for fans to forgive it. “The process is very similar to other projects,” Jesteadt told IndieWire over a recent Zoom call, his use of the present tense reflecting a job too massive to fit into the rearview mirror just yet, “but I’m more scared.”

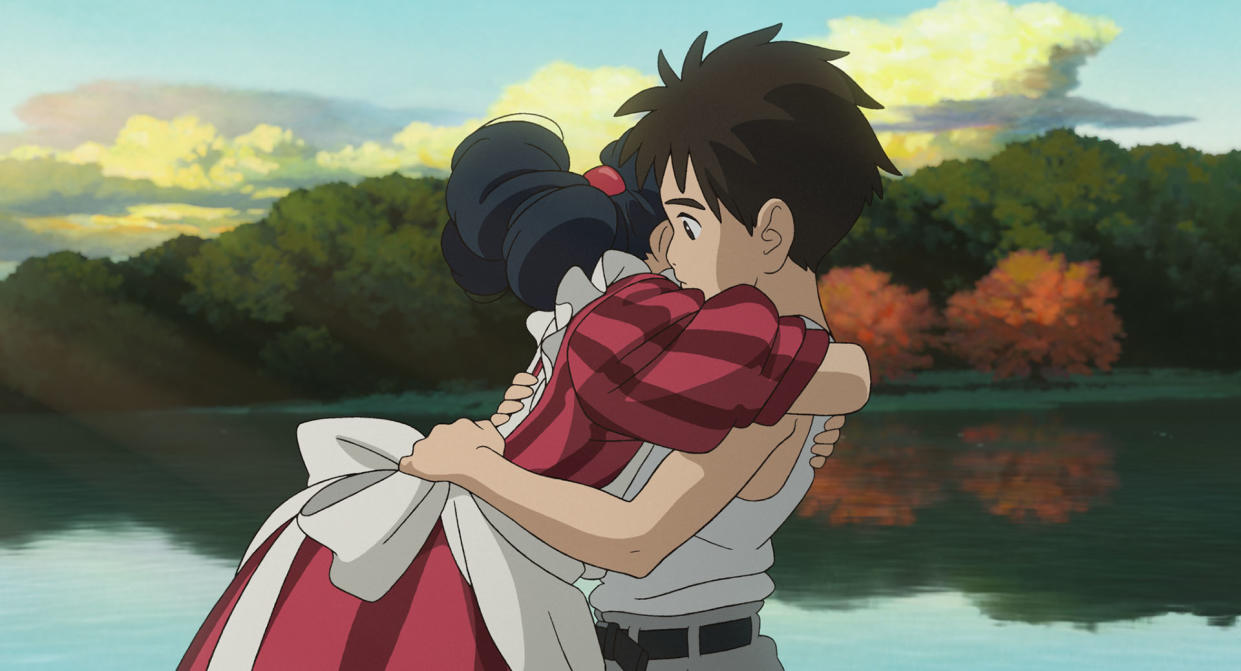

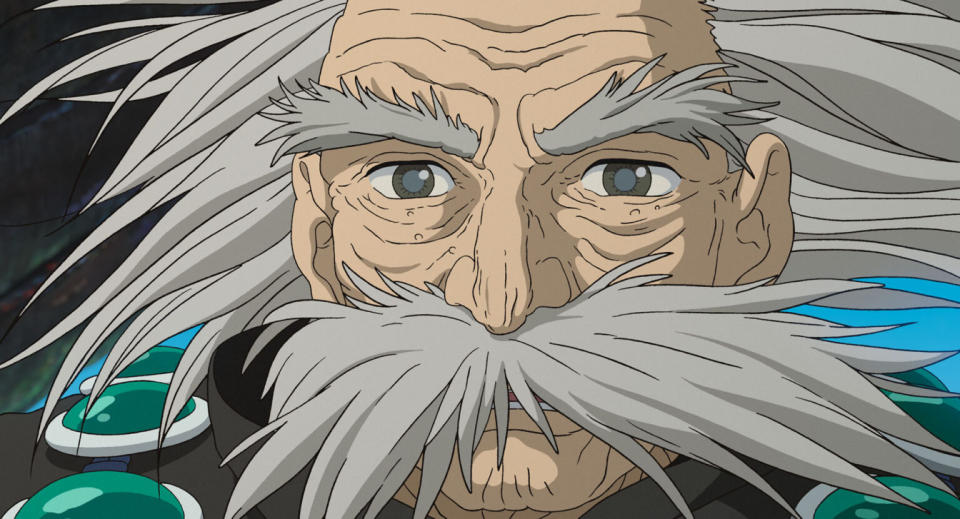

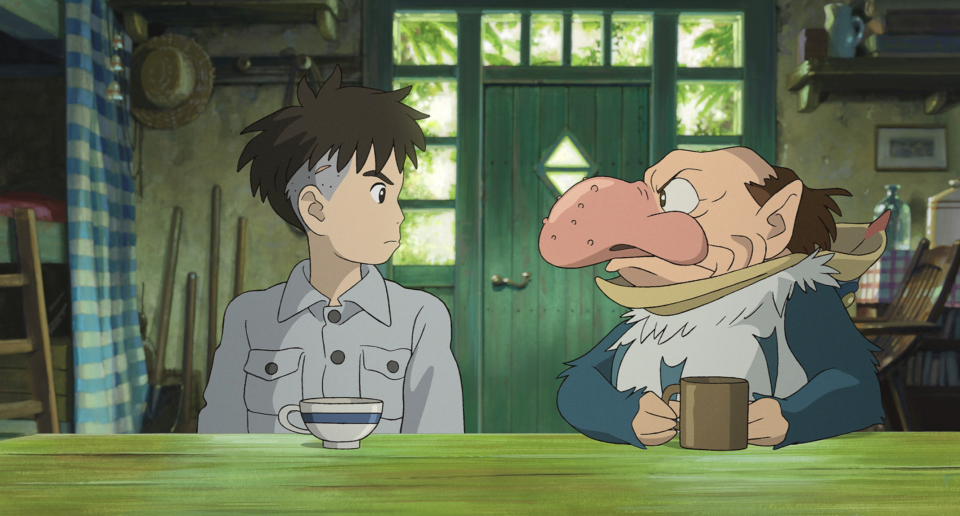

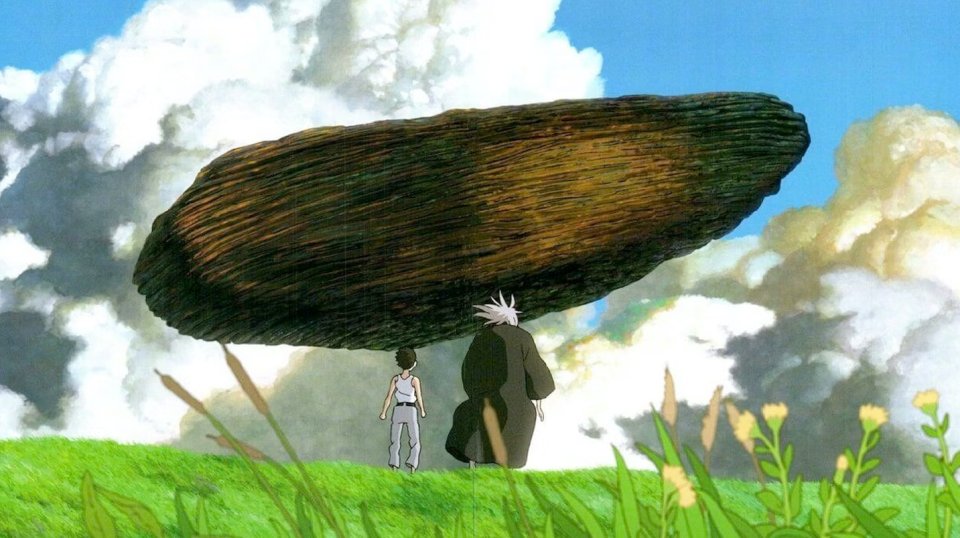

The pressure was high, but the degree of difficulty was even higher. “The Boy and the Heron,” as Miyazaki’s opus would come to be known outside of Japan, is both the most autobiographical and the most abstract of the filmmaker’s movies. The story of an embittered young boy named Mahito who moves to the countryside with his father and his aunt — his father’s pregnant new bride! — after his mother is killed in a Tokyo hospital fire at the height of World War II, the movie’s grounded first half gives way to a dreamlike second in which Mahito wanders into an alternate reality shared between the living and the dead; a place where the souls of unborn children are swallowed by hungry pelicans as they float up to the human world, and an old wizard — Mahito’s granduncle — is forced to save the dimension from collapse by rebuilding a wobbly tower of wooden blocks every three days.

That Jenga-like balancing act is all too familiar to anyone who’s ever been responsible for dubbing an important film, a process that requires people to recreate the essence of an entire universe with an entirely different set of pieces. In “The Boy and the Heron,” it becomes a bracingly simple metaphor for the moral order of the universe — one that arrives at the end of a film that constantly references the pain and beauty of Miyazaki’s previous work before leaving Mahito the challenge of imagining a better tomorrow for himself. For the team at GKIDS, however, that metaphor became an extremely literal challenge that confronted them from the start of the dubbing process: How would they honor the immortal history of Miyazaki’s imagination while also heeding his (potentially) final movie’s call to create something new?

On August 31, 2023, more than six years after “The Boy and the Heron” was first revealed but less than three months until GKIDS would open its dub in American theaters alongside the Japanese-language version, the team at GKIDS still wasn’t sure if they knew the answer. And that’s because they still hadn’t really started the recording process yet.

Which isn’t to say that Jesteadt and company had been twiddling their thumbs all that time. “The Boy and the Heron” had been a top priority for them long before the public even knew that Miyazaki was almost done making it. It was in the fall of 2022 — roughly nine months before Studio Ghibli would release a film with “Star Wars”-level hype in Japanese theaters without any promotion beyond a single poster — that Jesteadt was first invited to watch scenes from it under lock and key. GKIDS’ involvement was so secretive that it worked on the movie under the code name “Dakota.” In fact, it was so secretive that, for a while, the company could hardly work on the project at all.

“We were let inside very early, which is a fantastic privilege,” Jesteadt said, “but it means that we couldn’t tell people about it, so there was a delay in terms of when we could get to proper work on it.” The footage that had been screened for Jesteadt was totally silent, as Ghibli doesn’t record the Japanese-language dub or Joe Hisaishi’s score until the animation is finished enough for the talent to perform against; he would have to wait until the spring to get a fuller sense of Miyazaki’s vision. All he could do in the meantime was dreamcast the people who might be able to breathe life into the wordless characters he’d seen.

But it wouldn’t have behooved Ghibli to keep GKIDS completely in the dark. On the contrary, the two studios worked in close collaboration on “The Boy and the Heron,” even when everything about the project was still top secret. “This is a very complicated film,” Jesteadt said, “and I don’t think Miyazaki will ever do an interview where he lays out what it all means. But we asked a lot of questions, and we got a lot of answers back,” many of them from Ghibli co-founder and frequent Miyazaki producer Toshio Suzuki. “I feel really privileged to have what feels like a skeleton key for what things were supposed to represent or mean,” Jesteadt said.

Typically, Jesteadt and his team audition celebrity voices by editing audio from the actors’ past work to footage from the new movie, but in this case Ghibli provided a lot of helpful insight into its own casting process — insight that reflected Miyazaki’s intention to frame “The Boy and the Heron” as a culminating final work.

“They told us that casting was a really important aspect in regards to how they conceive this movie as being a love letter to the studio,” Jesteadt said, “and as perhaps the final Miyazaki film that there would effectively be cameos from people that audiences might recognize as voice actors from previous films. It was a big deal for them that the actor who played Howl in ‘Howl’s Moving Castle’ returned as Mahito’s father, and they told us it would be great if we were able to do a similar stunt. So we tried to do that as much as possible with people who had appeared in previous dubs.”

Sure enough, Christian Bale — who voiced Howl in Disney’s Pete Docter-directed dub of “Howl’s Moving Castle” — is back to play Mahito’s father. Willem Dafoe, who voiced the villainous Lord Cob in Goro Miyazaki’s much-derided “Tales from Earthsea” gives a moving single-scene performance as an anguished pelican, while a raspy Mark Hamill — of “Castle in the Sky” fame, among other fantasy adventure films — breathes magnificent life into the role of Mahito’s granduncle. “Earwig and the Witch” alum Dan Stevens is such a devoted Ghibli fan that he agreed to come back and deliver a few lines as one of the many different henchbirds that do the bidding of Dave Bautista’s Parakeet King (“It’s very cool to get a sneak preview of a new Miyazaki movie,” he told me, “and to be in the mix for what might potentially be the last one is just epic”). So did Tony Revolori and Mamoudou Athie.

It turns out that landing big names is a lot easier when it comes to casting a Miyazaki film. As Jesteadt explained it: “We’ve had a lot of communication with agents for years where they said, ‘I just want you to know that if another Hayao Miyazaki movie comes through, please give me a call before you talk to anyone else.’ So we had a pretty big arsenal of people who we knew were Ghibli fans, and might bring that energy into the performance.”

Karen Fukuhara of “The Boys” had frequently reminded her representation that she wanted to play a part — any part — in a Miyazaki film, and when the call finally came the actress was getting ready to attend a Joe Hisaishi concert at the Hollywood Bowl. She wound up landing one of the movie’s most crucial roles, fulfilling a dream she’d had since watching Ghibli movies with her mom as a child in Japan.

For the most part, Ghibli’s self-referential emphasis on continuity made things relatively straightforward, but the studio threw a major curveball when it came to one of the most crucial roles: The Gilbert Gottfried-esque heron who taunts Mahito with rumors that his mother is still alive and terrorizes the boy around his new house before revealing that he’s actually a giant-nosed little man wearing a heron suit as a disguise. The mere sight of the character was enough to give Jesteadt a clear indication of who to cast in the role: “Danny DeVito. Done.” But that isn’t exactly what Ghibli had in mind. “They said, ‘Oh no, in Japan it’s actually going to be played by a young, 30-year-old hot singer-actor guy [Masaki Suda],’” Jesteadt laughed. “I was like, ‘What!?’ They said, ‘Yeah, so for the English dub we want someone who matches that age and would also be unusual in the role.”

Enter: Robert Pattinson.

The “Batman” star was definitely a left-field pick, but he was on GKIDS’ radar for a reason. “One of the things that we were talking about with Ghibli was his role in ‘Good Time’ and his desire to play characters that don’t fall into a typical matinee idol filmography,” Jesteadt said, and even a quick glance at his body of work would suggest that Pattinson’s art-forward tendencies have only gotten stronger over time.

As GKIDS’ Director of Acquisitions and Development Rodney Uhler remembers, “When we introduced the film to him, he was, I would say, giddy with excitement. He was nothing but enthusiastic about the project, not only because of the film but also because of the prospect of doing this role in particular. We didn’t offer him a platter of roles — we offered him only the Heron, and he was very, very excited about being presented with a role as complicated and nuanced as this one.”

In fact, Pattinson was so excited about the role that he showed up to his first recording session in Los Angeles ready to prove that he was the right person to do it. Voice director Michael Sinterniklaas initially had his doubts (“When Pattinson’s name came up,” Sinterniklaas said, “I thought he’s a fine actor but there was nothing in his body of work to indicate that he could do this crazy thing”), but Pattinson was quick to dispel them. “When he came to our studio in L.A.,” Sinterniklaas said, “he was like ‘OK, I’ve been thinking about this role and I recorded some stuff. Do you want to hear it?’ And he whips out his iPhone and plays some stuff that he’s just been doing in the Memos app and it was already the voice. I was like, ‘Oh, bingo, you’ve already got the character.”

What Pattinson played for Sinterniklaas was the result of several weeks spent in pursuit of a nasal growl that sounds like a menacing cross between Gollum and the Cryptkeeper, but laced with pockets of softness that gradually allows the Heron — a puckish stand-in for Suzuki in a film about Miyazaki’s complicated friendship with his Ghibli co-founders (Takahata is represented by the great-uncle) — to soften into a reluctant ally for Mahito in his journey to the heart of another world. Not in a million years would you ever be able to guess the actor behind the bird, and even when you know who it is there are only a few moments in the movie you’ll actually believe it.

But Pattinson’s casting is hardly a gimmick. On the contrary, the taunting cruelty of his performance and the begrudging way in which that cruelty is embarrassed by Mahito’s flawed but genuine pursuit of a more loving future, reflects a deep understanding of Miyazaki’s creative ethos. Pattinson had never done proper voice work before, let alone a dub (after talking Pattinson through the process, GKIDS gave the actor an opportunity to opt out if he felt like he couldn’t do it), but he threw himself into the process with such vigor that recording the entire part only took a couple of days. “He knew he could do it,” Uhler said, “and he showed up and delivered magic.”

The role of the Heron is particularly important to Miyazaki’s film — and to its various dubs from around the planet, many of which were being recorded at the same time as GKIDS’ English-language version — because the bird acts as an intermediary of sorts between the real world and the fantasy realm inside the grand-uncle’s tower. And while Pattinson’s performance is rather faithful to the tone of the Suda one on which it’s based, his character speaks to the self-divided nature of the movie around him, which itself reflects the internal tension at the heart of any great dub: As Mahito discovers in his own way at the end of the film, truly honoring the spirit of an original sometimes requires you to put your own spin on it, or maybe even defy it altogether.

That delicate balance between translation and adaptation — between preserving the soul of Miyazaki’s work and treating it like a living thing — was at the forefront of Sinterniklaas’ mind from the moment he first watched “The Boy and the Heron” under extreme lockdown earlier this year. “I remember halfway through the movie going, ‘Oh my God, I think I know what Miyazaki is saying,’” Sinterniklaas said. “He’s saying goodbye and passing the torch.”

A lifelong Ghibli fan whose mother was born in Japan around the same time as Mahito, and who struggled through similar bouts of loneliness and dislocation, this project was already personal for the voice director, but now that he knew the movie was about the same transference implied by its existence, the stakes had been raised even higher. His job wouldn’t just be to bring the film to an English-speaking audience and bridge the gap between its grounded drama and fantasy elements; his job, if he really wanted to heed the message that Miyazaki seeds into this story, would have to be additive as well.

“My personal north star for every dub is to give the same experience to a non-native audience,” Sinterniklaas said. “So it’s really about serving the original intent, but doing so in a way that feels immediate and personal and not painted by numbers.” For Sinterniklaas, the greatest risk for a well-intentioned voice director is getting lulled by the sound of the voices they’re trying to dub over.

It was a trap that he almost fell into when working with Fukuhara, who plays the role of Lady Himi — a character Mahito encounters in the movie’s fantasy realm — and ultimately delivered the dub’s most poignant performance. Sinterniklaas previously collaborated with Fukuhara on “Star Wars: Visions,” and he had vouched for her ability to nail one of the trickiest parts in Miyazaki’s entire oeuvre, but halfway through the recording process, he realized that Fukuhara, the only native Japanese speaker in the cast, was so immaculately emulating what singer-songwriter Aimyon did in the Japanese version that she wasn’t quite jibing with the rest of the voices.

That kind of mismatch is the most common and damaging problem in the history of anime dubs, many of which have been impossible to engage with because it sounds like the characters aren’t really speaking to each other. “Dubbing is such a complicated magic trick of trying to make something seem organic,” Sinterniklaas said. “Not only are you putting something in a new language, but you’re also trying to make it sound like people were talking to each other when none of the actors were even in the same room.”

Fukuhara didn’t have any frame of reference for what the rest of the dub would sound like when she stepped into the booth (when she and Stevens spoke to IndieWire over Zoom for this article, it was the first time the two of them had ever met), and so it was up to Sinterniklaas to steer her in the right direction. “For dubbing,” Fukuhara said, “I usually try to emanate the essence of the original voice cast because I believe that’s why they were chosen in the first place, and so I was trying to match Lady Himi’s voice because I thought that was what I was being called upon to do. But eventually, Michael said, ‘That sounds too Japanese.’ The way I was saying the words, and also my reactions. He asked if we could make it more Americanized, and in doing so he gave me permission to fly free and really put my own twist on it. He pushed me to be more emotional — more vulnerable — than the original recording.”

And by embracing that vulnerability, Fukuhara tapped into a hidden well of strength in Lady Himi. Her performance isn’t broader or more instructive than Aimyon’s, but it’s emotionally lucid in a way that allows the most powerful moment in the movie to burn with new layers of feeling. Sinterniklaas is still awed by the depth of feeling that Fukuhara was ultimately able to suffuse into her character, and her ability to make it sound as if she were standing in the same room with the young actor who plays Mahito (Luca Padovan) and using his energy as kindling for her own performance.

In truth, Fukuhara had to act against the material that was available to her at the time, which meant a hodgepodge of the Japanese audio and whatever parts of the English dub had already been recorded. For some, that was a new challenge. For a guy like Dave Bautista, who spent three “Guardians of the Galaxy” movies talking to a tennis ball as if it were a sentient alien tree, not so much. But that inconsistency could have presented its own problems, if only because every member of the cast was forced to work under a different set of circumstances. “The heron got to hear the boy, but the boy never got to hear the heron,” Sinterniklaas said, as Padovan recorded all of his dialogue before Pattinson stepped in the booth.

If it was mind-blowing for the young actor to learn that he’d be sharing scenes with two different Batmans (and Sinterniklaas insists that he definitely was), you’d never be able to tell from the stoicism of his performance. “Ghibli’s version of Mahito sounds mature,” Sinterniklaas said, “and we had to match that. It’s a tricky character because he’s not a cute, cuddly, huggable lead like we’ve had in the past, and he makes himself more distant in the first half of the story. Luca did an extraordinary job of relating Mahito’s self-reliant streak.”

That ability was key to casting a role that was open to a wider number of candidates than any other. “Whenever I’m casting kids,” Sinterniklaas said, “I want to find people who are good actors and get the thought of the thing, not just the sound of the thing. We had a slogan at NYAV Post [the recording studio Sinterniklaas founded] that we used as a screensaver for years, and it said ‘choices > voices.’ Even though dubbing is a lot more about a result than most things in the arts, my approach is always as not result-oriented as possible.” There are all of these rigid constraints and specific targets that a voice performer has to hit, but they have to make hitting them feel like the most natural thing in the world, like a downhill skier carving the perfect slalom between two different pairs of invisible gates. And oftentimes the only way for actors to do that is to carve their own path.

For Bale, who plays Mahito’s father with a mid-Atlantic accent that splits the difference between an American twang and his natural speaking voice, that meant creating the character from the inside out. Mahito’s father is a Japanese business tycoon whose capitalistic pursuits have pushed him to adopt foreign attitudes and aesthetics (he assigns Mahito to live in the Western-style house that’s next to the main building on his property), and Bale and Sinterniklaas seized on the various syntheses that might erupt from that kind of culture clash; on the fault lines of a man who profits from death while doing everything in his power to make a better life for his son.

“Nothing is clear-cut and cartoonish in a Miyazaki film,” Sinterniklaas said,” and so Christian and I had a lot of conversations about the nuances of being an industrialist during wartime.” They focused on what kind of things a man like that might pay attention to, and how he might express his love. They softened his word choices around Mahito (Bale’s character refers to himself as “daddy”) but doubled down on the way that he sees the boy as more of a brand extension than a person in desperate need of his own empathy.

Florence Pugh effectively plays two roles — an old woman who lives at Mahito’s father’s estate, and a seafaring young badass who sails into the story once Mahito enters his grand-uncle’s tower — and the dual nature of her performance offered its own opportunity to go deeper into the basic fabric of Miyazaki’s film. “That was one of the parts we were most scared of casting,” Uhler said, “because it’s both an emotional heartbeat and a comedic highlight, and Florence spoke so authentically to both of those aspects. She did a phenomenal job.”

Pugh is flawless in each of her parts, but what is striking is how loose and funny she is as the frail granny in the first half of the movie. In a strange quirk of timing, GKIDS got permission to push the character a few stops further in that direction because — just a few days into the recording process — Ghibli had its first opportunity to watch the Japanese version with an English-speaking audience. Nobody in the crowd knew it at the time, but the TIFF premiere of “The Boy and the Heron” in early September was essentially the glitziest test screening of all time.

“I think that was really eye-opening for Ghibli,” Jesteadt said, “because we were in the middle of a lot of creative conversations with them at the time. They sat down with us the day after the premiere and were like, ‘Wow, everyone seemed to be laughing a lot more than we thought they would. Is this film funny?’ They got to compare the Western audience reaction compared to that in Japan, where people tend to be very stoic in theaters. At TIFF, a lot of stuff that local audiences liked was just killing.” It was a fortuitous moment for the folks at GKIDS, who had recognized how English-speaking crowds might respond to some of the film’s humor and were already nudging the material in a direction that might reassure local audiences that it was OK to laugh. After that screening, Ghibli was a lot more comfortable with the direction of the English dub.

The final recording session for GKIDS’ dub took place during the first week of October — or about six weeks before it was due to open in theaters. They sent it to Ghibli once it was finished and began the harrowing experience of waiting for a response. “I was definitely nervous,” Jesteadt said, “but to be honest, the whole thing was so low-key.” The verdict came in the form of a short email that Jesteadt paraphrased as saying: “Wow, it sounds great. Alright. Fantastic.” And that was it. Perhaps the anticlimax was to be expected; the English-speaking world might be Ghibli’s biggest export market, but the studio was also in the process of fielding dubs in other languages from all over the world.

More to the point, Ghibli knew what they were getting, as by then GKIDS had been working closely with them on the project for more than a year. The recording process itself may have been a whirlwind two months, but time had been on their side almost every step of the way. “Time was the real innovation on this project,” Sinterniklaas said. “In a world of streamers, it’s usually all about harder, faster, and cheaper, but something like this needs time. Ghibli took their time to make this film, and I feel like it would have been vandalizing to just slam the dub through. We had deadlines, but Ghibli was generous with them at every turn, and we ended up delivering [the final product] later than we thought we would.”

“The Boy and the Heron” is a stained glass window in the church of animation, and GKIDS had the luxury of treating it as such. Jesteadt had time to wrap his head around the big picture, writer Stephanie Sheh had time to script the adaptation, production manager Clark Chang had time to bring the pieces together, and so on. It wound up being the smallest team that GKIDS has ever assigned to a Ghibli film, but they worked on it with a focus that allowed them to plumb the deepest recesses of the text, and breathe it full of a new life all its own.

It can be hard to remember now, but the prospect of GKIDS putting its own spin on this film didn’t always seem like a good thing. When the company’s role in the project was finally announced over the summer, the welcome news was accompanied by the less welcome detail of a title change. Fans had spent years anticipating “How Do You Live?” (a mordantly delicious Miyazaki title if ever there was one, and also the name of a novel from his childhood that factors into the plot of this film), and now they were suddenly confronted with the much simpler “The Boy and the Heron.” It was an unexpected wrinkle that seemed more in line with the way Harvey Weinstein used to handle Ghibli’s films than it did GKIDS’ more reverent stewardship. But the truth — and its ultimate legacy — paints a much warmer picture.

“There was a total press blackout on the film in line with the release in Japan,” Jesteadt said, “but because of our long relationship with Ghibli, we asked if we would be able to announce that we had the rights, as we needed to be able to set up a big fall release. It was at that time that Suzuki asked for a title change. The call came from inside the house. I can’t speak to the exact reasons for the title change, but I think there was a desire to move away from the name of the book, as people were constantly mistaking the movie for an adaptation.”

Jesteadt and his team fiddled around with a few different ideas, all of them less than good. “We talked about ‘The Tower Master’ or ‘The Grand Uncle,’” he said, “and our feeling was that they felt a little too much like hard fantasy. We tried a lot of different permutations of ‘How Do You Live?’ but ended up choosing the option closest to Suzuki’s original suggestion.” “The Boy and the Heron” may not be quite as dramatic as the film’s original title, but Jesteadt has found some wicked poetry in it all the same. “Miyazaki based the characters in this movie on people in his life,” he reminded me, “and the heron is based on Suzuki. To me, there’s something very meta and very funny about this heron — this trickster — inserting himself into the situation and suggesting we give the movie an international title [with his name in it].”

It’s an argument tailor-made for the same Ghibli purists who scoffed loudest at the title change, but the movie itself might be all it takes to sway them in the end. As Jesteadt observed, there’s a fable-like quality to “The Boy and the Heron” that serves the moral dimension of Miyazaki’s latest and possibly final film. It speaks to the timelessness of a story designed — in the most explicit terms — to outlive its author. A story designed to be transformed by the people who tell it, even though its essence is singular in a way that no one would ever be able to erase altogether. It’s the story at the heart of a movie that will stand as a monumental achievement for as long as we can imagine, even as the world continues to turn its back on beautiful things, and the infrastructure that allows for their creation continues to crumble. “The Boy and the Heron” tells us to build our own tower, and GKIDS, with its bold and deeply personal English dub, has done just that.

“The Boy and the Heron” is now playing in theaters.

Best of IndieWire

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Solve the daily Crossword