‘The Boy and the Heron’ Review: Hayao Miyazaki’s Final Masterpiece Is the Dream-Like Farewell of an Immortal Man Preparing for His Own Death

Editor’s note: This review was originally published at the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival. GKIDS releases the film in theaters on Friday, December 8.

How does someone follow one of the greatest and most profoundly summative farewells the movies have ever seen? By definition, they don’t. They retire, or they die. Or they retire and then they die. In some rare cases, it even seems like they die because they retired.

More from IndieWire

And then there’s 82-year-old filmmaker and Studio Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki, always in a category of his own, who’s formally or informally quit the business no fewer than seven times of the course of his illustrious career, most recently after the 2013 release of his magnum opus “The Wind Rises.” A fictionalized biopic about aeronautical engineer Jiro Horikoshi, whose most visionary designs were built with forced Korean labor and deployed at the wasteful mercy of Japan’s World War II campaign, the film doubled as a devastatingly raw self-portrait of an artist struggling to reconcile the cost and value of his own creations — to reconcile the purity of his imagination, and the violence required to make it real.

It was the Ozymandian signoff of a cinematic titan looking on his works, ye mighty, with despair, and straining to convince himself that the ugliness of our world doesn’t invalidate the beauty of our dreams so much as the beauty of our dreams validates the ugliness of our world. “The wind is rising,” Horikoshi concludes, quoting a poem from the French writer Paul Valéry as he watches one of his glorious planes glide through the air. “We must try to live.” The only question that remained, of course, was how.

It was a question “The Wind Rises” posed implicitly but also rhetorically, as Miyazaki knew that it was also one that everyone would have to answer for themselves. And by “everyone,” I mean everyone; try as he might, the self-torturing Miyazaki just couldn’t let himself off the hook.

The movie world’s least convincing retiree had made a film that was clearly meant to serve as the period at the end of his peerless career, and yet he couldn’t help but turn its final moments into a taunting ellipsis. Shocked as some (i.e. me) were by the announcement that Miyazaki would dare to make another movie after “The Wind Rises,” that shock immediately softened into the stuff of head-shaking inevitability when the title of his new last movie was revealed in October 2017. It would, of course, be called “How Do You Live?” It would be the ultimate statement from someone who had left himself no choice but to make it before he left us for good — someone who had to unretire, for the eighth and final time, in order to die on his own terms.

Needless to say, he wasn’t thrilled about that. “There’s nothing more pathetic than telling the world you’ll retire because of your age, then making another comeback,” Miyazaki wrote upon starting work on “How Do You Live?” (excerpts from his journal were included in the film’s press notes). “Is it truly possible to accept how pathetic that is, and do it anyway? Doesn’t an elderly person deluding themself that they’re still capable, despite their geriatric forgetfulness, prove that they’re past their best? You bet it does.”

Well, yes and no. It’s true that “How Do You Live?” — which tells an original story that borrows its title from Genzaburo Yoshino’s 1937 novel of the same name, and has been inexplicably rechristened “The Boy and the Heron” for its international release at Studio Ghibli’s behest… despite the fact that Yoshino’s book acts as a crucial plot point in a film whose climax hinges upon an obvious stand-in for its writer-director literally asking the audience “How do you live?” — isn’t Miyazaki’s best film. It lacks the full kineticism of “The Castle of Cagliostro,” the fury of “Nausica? of the Valley of the Wind,” the adventure of “Castle in the Sky,” the Totoro of “My Neighbor Totoro,” the effervescence of “Kiki’s Delivery Service,” the romance of “Porco Rosso,” the grandeur of “Princess Mononoke,” the beguilement of “Spirited Away,” the floridness of “Howl’s Moving Castle,” the hamminess of “Ponyo,” or the emotional mega-wattage of “The Wind Rises.”

Crucially, however, “The Boy and the Heron” contains aspects of all of those things (in addition to more overt references to the anime godhead’s previous work). And while this dream-like warble of a swan song may be too pitchy and scattered to hit with the gale-force power that made “The Wind Rises” feel like such a definitive farewell, “The Boy and the Heron” finds Miyazaki so nakedly bidding adieu — to us, and to the crumbling kingdom of dreams and madness that he’ll soon leave behind — that it somehow resolves into an even more fitting goodbye, one graced with the divine awe and heart-stopping wistfulness of watching a true immortal make peace with their own death.

It should be understood that “The Boy and the Heron” is among the most beautiful movies ever drawn, and that being immersed in an animated world so lush and alive after a decade of “Minions” feels like… well, remember when Anton Ego tasted his first bite of that magical ratatouille? Now imagine that he’d almost exclusively eaten 3D-printed soy meat for an entire decade before sitting down for that fateful meal. It feels kind of like that.

But for all of their artistry and joy, Miyazaki’s films have always reflected a rather dim view of humanity, one typically expressed through his characters’ greed and penchant towards ecological suicide. They’re the ecstatic creations of a bitter man who’s devoted his time on Earth — often miserably, at the direct expense of his loved ones, and for reasons that not even he entirely understands — to making things of unsullied wonder. “The Boy and the Heron” is structured as a head-on collision between those seemingly incompatible mindsets.

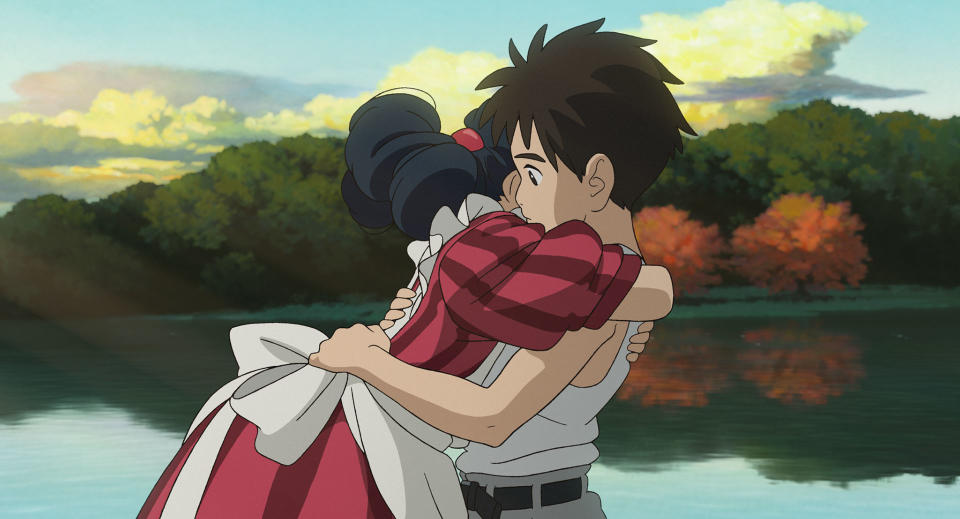

The first half of the story introduces us to Mahito Maki (voiced by Soma Santoki), a 12-year-old boy whose mother was killed in a 1943 Tokyo hospital fire. We’re introduced to Mahito through his dreams, where he’s surrounded by a city’s worth of silhouettes who watch as the boy’s mother erupts from the flames like a screaming phoenix (a fitting start for a film that erupted from the ashes, itself). In waking life, Mahito’s strapping father — who owns an air munitions factory — has already remarried his sister-in-law, thus making Mahito’s aunt Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura) his new step-mom. Also, she’s pregnant with his dad’s baby. Unsurprisingly, Mahito isn’t over the moon about any of this, which puts the already sullen tween in a most sour mood as he arrives at his new aunt-mom’s lavish country with a growing malice in his heart.

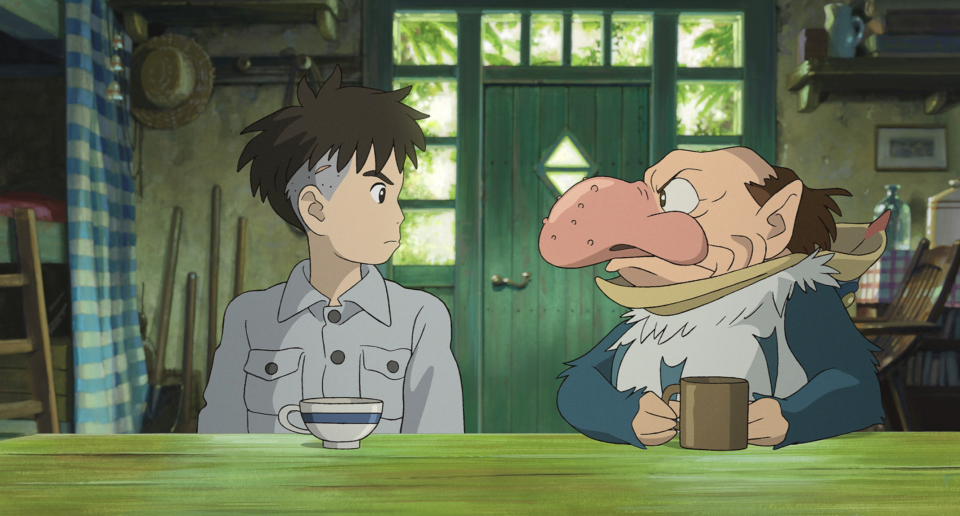

Waiting for the boy on the roof of the estate — which is split between a Japanese-style main house and the Western-style residence where Mahito stays, a cultural schism reflective of a film that will similarly come to straddle life and death, reality and imagination — is a gray heron (Masaki Suda). And while the long-legged bird may seem rather elegant from a distance, this particular creature soon reveals itself to be anything but. Not only is it an absolute menace, smacking its beak into the window of Mahito’s bedroom and cawing about his dead mom with a voice that sounds like a malevolent homage to Gilbert Gottfried, but it turns out it’s not even a heron, but rather a small man with a bulbous nose and horrifying teeth in disguise (memories of Jigo slithering through the third act of “Princess Mononoke” inside a boar carcass might come to mind).

The heron eventually speaks to Mahito, goading him towards a mysterious tower the boy’s late great-uncle built in the woods beyond the house (access to which requires crawling through a “Totoro”-esque garden path). The mischievous heron tells our hero that his mother is alive, and that she will guide Mahito should he dare to go inside the tower. Which, of course, he does at the end of the movie’s first hour, following Natsuko and accompanied by one of the many old maids who tend to her house.

And so what to that point has been Miyazaki’s most grounded film in many respects becomes his most abstract, as the second half of “The Boy and the Heron” plunges us and Mahito alike into a precarious fantasy world that maps onto waking life with the metaphorical uncertainty of a dream. Some connections are more literal than others. Mahito meets a seafaring woman named Kiriko, who appears to be a younger version of one of Natsuko’s maids. Standing on the bow of a massive wooden shipwreck one night, they watch as smiley little sprites called waru waru — imagine the Kodamas from “Mononoke,” but much cuter — ascend towards the sky, human souls hoping to be born into the world above. Later, the expressionless soldier who the boy saw marching towards war as he made his way from Tokyo is neatly extrapolated into an army of starving humanoid parakeets, all of whom are in the mindless thrall of their destructive king.

For the most part, however, the imagery that Miyazaki conjures here is more broadly symbolic of his lifelong pacifism and disgust for his fellow man, and the film’s threadbare story — patchy and moth-eaten in some ways that serve its purpose, and other ways that don’t, including a certain mid-scene cut so abrupt that I wondered if the DCP had suffered a glitch — is only carried along by the strength of the director’s signature undercurrents. Chief among them: The ambient tension between the dreams that bind our world together and the violence that threatens to rip it apart.

Stunningly gorgeous and wrenchingly tragic in equal measure, the waru waru sequence is only complete when a phalanx of pelicans swoop in and feed off the slow-floating souls. The birds are hellbent on flying high enough to touch the heaven-like human realm above the sky, but they singe their wings in the process of trying to achieve a goal so far out of reach that their babies have forgotten how to even get off the ground. The wind rises, but gravity always prevails in the end.

Split, as most dreams are, between obviousness and impenetrability, this second half of “The Boy and the Heron” sustains the ethereal unease of the ghost train sequence from “Spirited Away” for the better part of an entire hour, a connection that practically makes itself by the time Mahito is forced to do menial labor in order to pay for his passage through the underworld. Reflective as this film might be, however, it never leaves you with the feeling that Miyazaki is repeating himself.

On the contrary, “The Boy and the Heron” finds the anime legend standing atop the rubble of his almighty career — an unscalable mountain of stunning masterpieces and withering memes, of plush toys and private traumas, of singular brilliance and common frustrations — and squinting against the sunset to measure the worth of that creation before he leaves it all behind. He’s confronting familiar topics from a new perspective, and with the urgent disarray of someone who knows that he’ll never be able to address them again.

If “The Wind Rises” was a woundingly piercing work of self-examination, “The Boy and the Heron” is by contrast a crushingly poignant work of self-elimination. Once more, Miyazaki is questioning the purpose of artistic creation in a world so prone to ruin, but this time he’s asking it of us. Why do we do anything when everything seems to be crumbling before our eyes, and how do we find the strength to do it? If Miyazaki knew the answer, he would have told us by now; he wouldn’t have felt the need to devote the twilight years of his life to a painstakingly animated movie that he feared he wouldn’t be able to finish before war — or death by any other means — rendered the whole project a waste of time. It’s not “what will we do without Miyazaki’s genius?,” but rather “what will we learn from the legacy of his failure?”

That air of bittersweet futility is at its thickest during a climactic meeting between Mahito and his missing great-uncle, as the boy — in terms so basic they reflect both the naivete of a child and the wisdom of an old man — is given the impossible task of restoring equilibrium to a realm that’s lost any sense of balance. That might seem like a particularly cruel request from a filmmaker who’s spent the brunt of his life struggling to reconcile the beauty of our world and the ugliness that it provokes, but Miyazaki asks it of Mahito without expectation. “How do you live?” He doesn’t expect a response any more than Mahito’s mother did when she hid a note to her son in a certain book that he only found after her death. He only hopes, as she did, that his memory will inspire Mahito to keep searching for an answer, even if only in his dreams.

“Build your own tower,” grand-uncle pleads before the spire he’s lived in for so long begins to crumble into dust. And the last shot of Miyazaki’s last movie — the simplest image in a film bursting with spectacular wonders — leaves us alone with all of the tools we might need to do just that.

Grade: A

“The Boy and the Heron” aka “How Do You Live?” made its non-Japanese premiere at the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival. GKIDS will release it in theaters on Friday, December 8, with special engagements starting Wednesday, November 22.

Best of IndieWire

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.