'Your radio friend': This Phoenix DJ played what he liked. A generation couldn't turn away

It was June 21, 1977, when the car in which Bill Compton and his girlfriend had been traveling swerved to avoid a bicyclist and plunged into the canal just north of Osborn Road on 48th Street. He was 31.

It was a tragic ending to a brilliant chapter in the history of Phoenix broadcasting with Compton on the verge of launching his own station.

“It was like royalty passing in this market when he died,” recalls Danny Zelisko, a concert promoter in metro Phoenix who had a Sunday night specialty show on Compton’s most successful experiment in freeform radio, KDKB-FM (93.3).

“It felt like the end of an era, you know?”

'We tried to find the good music': Linda Thompson Smith recalls her days at KDKB

Little Willie Sunshine hits the airwaves

A pioneering force in freeform radio still thought of in some circles as “the Voice of God,” William Edward Compton hit the metro Phoenix airwaves in his early 20s as the host of KRUX-AM’s KRUX Underground.

At that point, he was known as Little Willie Sunshine, a freewheeling maverick whose specialty show was a head-spinning trip through a musical landscape free of artificial boundaries, from rock ‘n’ roll to folk, blues, jazz and all points in between.

If Compton liked it, Compton played it.

Linda Thompson Smith, who worked closely with Compton as music director at KDKB, recalls her first impression of the man she knew as Little Willie Sunshine.

“It was one summer at the end of high school, beginning of college,” she says.

“And here was this guy with a magical voice and such great taste in music and somehow the ability to go into deep cuts and music that no one had ever heard before and get away with it. That was just amazing to me."

KEYX: How a low-watt radio station in a strip mall became 'the key to your musical future'

The birth of the KRUX Underground

Born in Henderson, Texas, Compton got his start in broadcasting as a teen in Tyler, Texas, going on to work in several markets from Dallas to Nashville before making his way to Phoenix where, in 1969, he was hired at KRUX by Valley broadcast legend Al McCoy.

Marty Manning, an Arizona Broadcasters Hall of Famer who retired after 50 years in radio in 2019, recalls the impact Compton's show had on the market.

"That's where the underground radio concept really started here in Phoenix," Manning says. "All of a sudden, this top 40 station turned into what Bill called freeform contemporary."

KDKB DJ Lee Powell was an instant fan of Compton's style at KRUX, the way he'd build his sets around a theme and blend these unfamiliar songs together in an almost seamless fashion.

"It was great to listen to, especially as someone who was really into music in those changing times," Powell says.

"He was the real deal, very bright and charismatic. He had the ability to make the listener feel like he was right there in the room or in the car with them. Just a magical guy."

'It was our Fillmore': Metro Phoenix had never seen a club quite like Dooley's

'It sounded like the voice of God'

Almost any conversation about Compton will inevitably work its way around to that magical voice that earned him a blasphemous nickname.

"Because it sounded like the voice of God," John Dixon, a DJ at KDKB and KCAC-AM before that, explains with a laugh. "He just had such great pipes and such a deep voice, it got your attention."

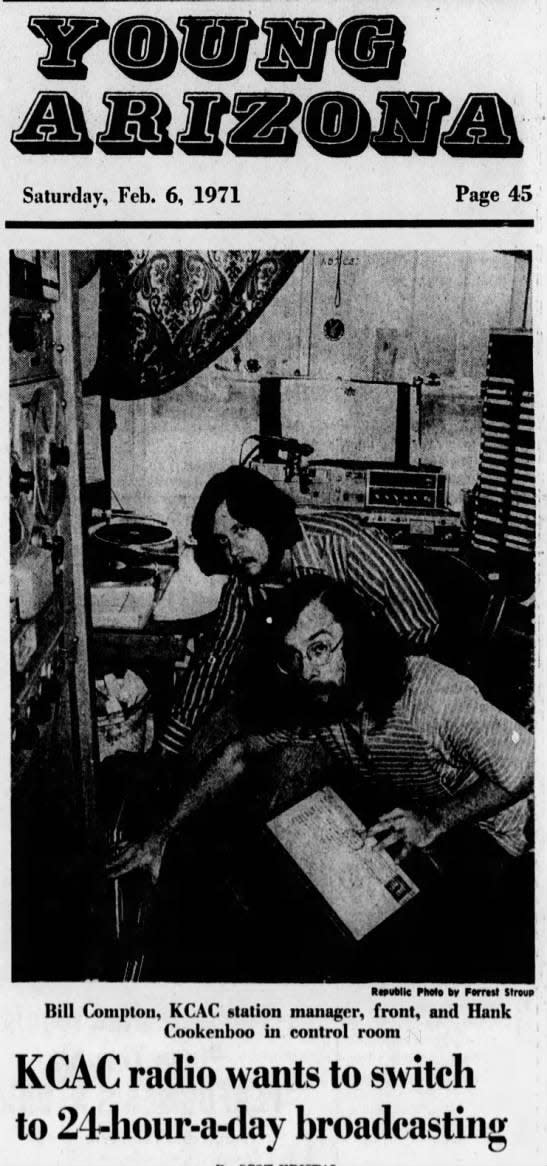

Compton briefly worked at KUPD-FM before finding a home at KCAC, a daytime-only, 500-watt station then housed on the south side of Camelback Road between Seventh and 15th Avenues.

KCAC was on the front lines of progressive radio in metro Phoenix, following several months of KNIX-FM testing the waters.

Compton was program director and an on-air personality, its format a natural extension of the freeform aesthetic he'd brought to the airwaves at KRUX.

As Dennis McBroom sums up the impact of what Compton did with those 500 watts, "He introduced the Valley to a type of radio we'd never heard before. Which was wide open."

Tommy Vascocu, who first encountered Compton as a KCAC sales rep long before he took over as general manager at KDKB, says Compton was a perfect fit for that emerging format.

"He was such a great spokesperson for the culture of young people at that time," Vascocu says.

Don't miss out! Your guide to all the best and biggest Phoenix concerts

KCAC: 'More than just a hit machine'

And he picked the perfect time to stage a sonic revolution.

"Bill was right there as radio was changing," Manning says.

"He had a background in Top 40 radio. So he was a professional. But what he brought to that was a sense of integrity — incredible integrity — and the concept that radio could be more than just a hit machine."

It's not that Compton was opposed to hits. Manning recalls the time he questioned KCAC spinning "Light My Fire" by the Doors.

"I asked Bill why," Manning says. "'It's a big Top 40 hit and we're the alternative station.' And he said, 'Because it's a good song.' It didn't matter to Bill that it was a hit. It was good."

As fate would have it, KCAC wasn't built to last.

"It was not a big signal," Vascocu says. "Day-timers had a more difficult time than full-time radio stations. And the fellow that owned it at the time was just about to go into bankruptcy."

But Compton made a go of it at KCAC, also known as Radio Free Phoenix, with an on-air staff that also featured Manning, Gary Kinsey (or Toad Hall, as listeners came to know him) and Hank Cookenboo, the childhood friend with whom he'd moved to Phoenix.

"The air talent played pretty much what they wanted to play," Vascocu says.

"It was freeform radio, a lot of call-ins and requests, which was really anathema to the Top 40 radio stations at the time, which were really tight-listed. So it was a totally different approach."

Stevie Nicks to play homecoming concert in Phoenix. Everything you need to know

'KDKB gave Bill a larger forum'

Dixon, who hosted a specialty show called R&B with Johnny D on Sundays at KCAC, says Compton's style of leadership was "surround yourself with good people, give them a lot of great music and let them go."

McBroom got his first taste of what it means to be a DJ thanks to Compton. He and Kinsey were attending Phoenix College at the time and Kinsey convinced him to drop by the station.

"That was actually my first time behind a mic," he says. "I wasn't paid but I got to sit down because Bill would let us go in and create."

In 1971, financial problems led to KCAC going off the air, with Compton and most of the staff going over to KDKB.

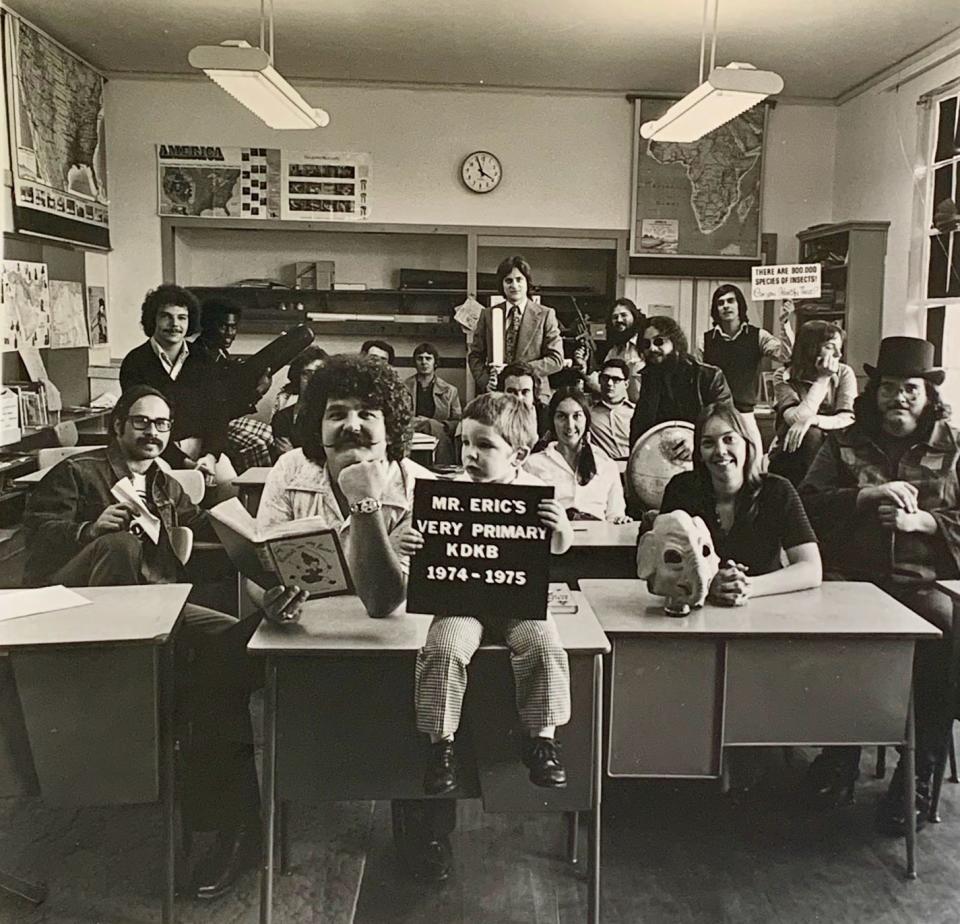

Dwight Tindle and Eric Hauenstein had met in Philadelphia after spending the weekend at Woodstock and immediately hatched a plan to launch what they believed could be the hippest FM station in the world as Dwight Karma Broadcasting.

The frequency they found was 93.3 FM, a struggling easy-listening station called KMND in Mesa, renaming it KDKB in honor of Dwight Karma Broadcasting. (The Krazy Dog Krazy Boy call-letter nickname came later.)

"Dwight came to Bill and the boys and said, 'I want to do a station,'" McBroom says. "And they literally took the KCAC staff with only a couple exceptions and went, 'Boom, we have a full-time FM station. Let's rock.'"

With that move, Compton's vision could be broadcast at 100,000 watts.

"KDKB gave Bill a larger forum, if you will," Powell says. "A larger stage, a larger audience. And Bill brought a lot of folks into the fold that had the same mindset."

'If we liked the music, it went on the air'

Thompson Smith started working the front desk at KDKB's Mesa digs (a former Safeway store on Country Club Drive) in November of '71, working her way up to DJ and music director.

"If we liked the music, it went on the air," she says. "And if the audience responded to it, it got played more. We let the people speak to it."

The sense of community Compton nurtured in that building often felt like family or what Thompson Smith refers to as a band of brothers.

"Everybody there was just so close," she says.

The vibe was somewhat more professional than it had been at KCAC, but Compton did his best to bring a human side to that increasingly professional environment.

"He was very open-minded, especially to people that knew and loved music," Powell says. "Obviously quite a leader. And he let you do your thing. Within certain parameters. If you were there, Bill trusted you."

Manning recalls a staff meeting at which Compton seemed to lose his cool.

"You had to sign logs in those days, and there was one guy who would just blow it off," Manning says.

"We had a staff meeting and Bill was really hard on him. When the meeting was over, I said, 'Boy, Bill, you were pretty rough on him.' Bill looked at me and said, 'Eric told me to fire him.' He was told to go in there and fire the guy. But he didn't. That's the way Bill was."

Zelisko was visiting Phoenix over Easter break his senior year of high school when he first experienced KDKB, which he credits as one of the primary reasons he moved here from Chicago.

"I could not believe this station," he says. "You'd find yourself just sitting in the car so as not to interrupt the set of music they were playing for you. You would wait for them to finish, whether it was 120 degrees outside or not."

When KDKB 'ruled the Valley'

With Compton at the helm as their program director, KDKB became one of the Valley's most popular stations.

"At that time, the station ruled the Valley," Powell says. "I mean, of course, there weren't that many stations. But we were getting huge numbers."

They were also breaking talented young artists, from Buckingham Nicks to Jerry Riopelle and a scruffy "new Dylan" from Asbury Park, New Jersey, named Bruce Springsteen.

"There was just so much great music going on and they were very, very open to it," Dixon says.

It helped that they were playing deep cuts.

"Most stations would just find one cut to play and they'd play that," Dixon says. "KDKB would play three or four cuts right away. So that was a cool thing, because it created careers."

In April of '74, Compton hired McBroom to join the fold.

"When I walked into KDKB, there were 10,000 albums on the wall plus another rack behind the DJ that was all the new music," he recalls.

"And these were Bill's instructions when I started: 'I want you to go in there and do the very best radio you can. And if you can remember the last time you played it, don't.'"

McBroom retired in 2017 after 47 years of "having fun" in radio.

"And the most fun I ever had, the best programmer I ever had, was Bill," he says.

"He gave us good direct advice. And he was nice. A lot of stations, the program director is the guy in the office upstairs or wherever. That was not Bill Compton. Bill Compton was a friend. That's how he treated us. We were friends. He was just the boss."

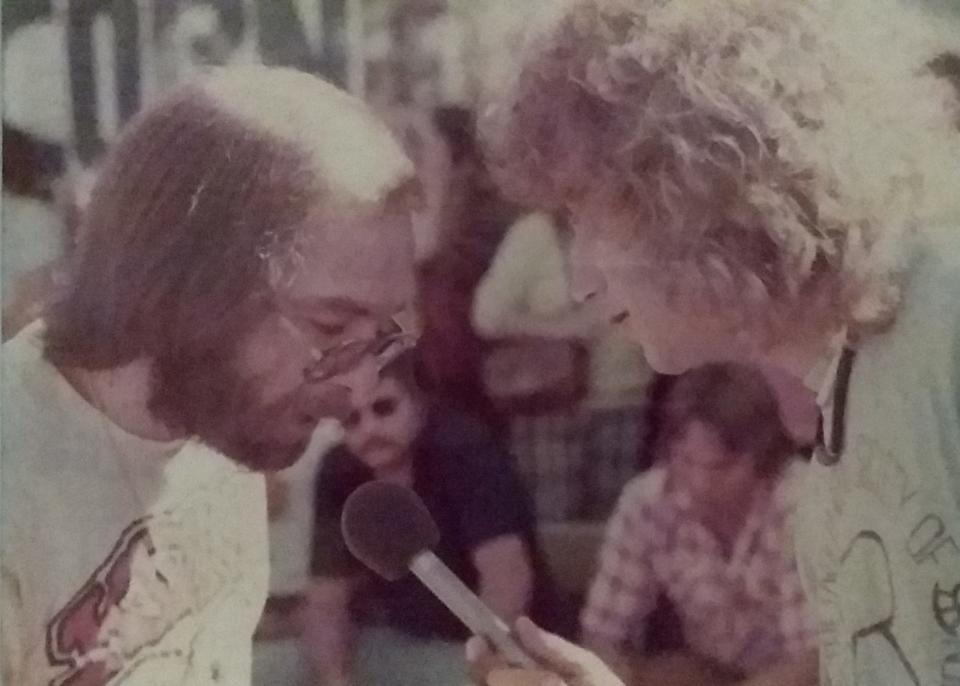

Working closely with local promoter Doug Clark and later Zelisko, Compton played a key role in landing many of the most important up-and-coming artists of that generation their first gigs in Arizona at the 2,650-capacity Celebrity Theatre.

As Vascocu recalls, "Bill would say, 'Doug, this is somebody you want to keep an eye on and think about bringing into the Celebrity.' Or Doug would get an inquiry from a booking agent and say, 'What about so and so? Can we make that work?'"

'KDKB singlehandedly broke Bruce Springsteen here'

Zelisko says that's how a lot of major artists broke into this market.

"Bill and KDKB singlehandedly broke Bruce Springsteen here," he says. "He was selling out the Celebrity when he was still doing 300, 400 people in New Jersey. That's how powerful the station was. And Bruce at the Celebrity was something to behold."

It didn't hurt that once the station got behind a show, it did its best to get the word out.

"You would hear the music on KDKB," Dixon says. "They would talk it up and promote the concerts. It was a very symbiotic relationship."

Powell remembers hanging outside the Celebrity with Billy Joel.

"I think it was the first time Billy came to town," he says.

"We were standing out front at the railing. And it's etched in my mind like it was yesterday. He climbed up on the first bar of the railing to see the cars coming into the lot. He was absolutely amazed at the amount of people coming in to see him. I remember those eyes of his, looking out, going, 'Wow, all these people.'"

The hub for everything that was cool in Phoenix

By that point, the station was part of the culture.

"It was unbelievable," Zelisko says. "Every bumper in this town had a KDKB sticker."

And it wasn't just about the music.

"It was a hub for everything going on in the Valley that was cool," Thompson Smith says. "And our public service commitment was higher than the FCC requirement. Because that's how Bill wanted it to be."

Every day at 6 p.m., they'd set aside their favorite records for an hour of news.

"That was unheard of back then," Powell says. "No music for an hour and public service programming?"

It's something Compton had been doing since his days at KCAC. He saw keeping listeners informed on issues of the day as a very important role a station could play in the community.

"When we were at KCAC, Bill and I were walking around the neighborhood one day, just talking," Manning says.

"I said, 'You know, a lot of people, they don't really like the fact that you break up the music to do this public affairs program. I was speaking for the average guy. And Bill said, 'Well, we're gonna do it anyway. Because they need it.'"

Manning laughs, then adds, "He had a really strong commitment to radio that mattered."

In 1976, the station won a Peabody Award for its public affairs program, Forum, which Thompson Smith says was a "pretty heavy-duty, in-depth" hour's worth of radio.

When Bill Compton split with KDKB

That same year, Compton parted ways with KDKB.

Thompson Smith says he was forced out.

"Most radio stations during that period of time wanted more control over what was happening on the air," she says. "They wanted Bill to come up with a format that they could control. And Bill refused to do that."

Zelisko and Vascocu say Compton quit after the station failed to deliver the ownership points he'd been promised.

"All of a sudden, he was off the air and people were calling," Thompson Smith recalls. "'What's gonna happen to the station?' 'Is the station gone?'"

At the time of Compton's death, he was about to purchase KDOT for $1 million and start his own station.

Zelisko had worked out a deal for Compton with Don Reno, the owner of Dooley's, the popular nightclub where Zelisko booked a lot of KDKB artists, to go in 50/50 on the million-dollar purchase price.

In exchange for his efforts, the promoter would get 5% and two weekend shifts at the new station.

"We got close," he says. "We almost got there. Then he had that accident."

McBroom says, "When he died, that whole thing went with him. It sucked for those of us that worked for him. It sucked for the listeners who were going, 'He's gonna do another one. He's gonna do another one.' It was a huge loss."

Thompson Smith was devastated.

"That's probably the first good friend I ever lost that way, out of the blue," she says. "I think I was in shock for a couple of days. Because that was my future. I was going back to work with him. And it was gonna be great."

In 1979, Jess Nicks, whose daughter Stevie was a KDKB staple with Buckingham Nicks and later Fleetwood Mac, opened an amphitheater on the grounds of Legend City, an amusement park on the border of Phoenix and Tempe, and named in Compton's honor.

"It was a fitting tribute, a musical tribute to this guy," Zelisko says of that first Compton Terrace, which closed in 1983.

A second Compton Terrace, a 20,000-capacity amphitheater, opened in 1985 next to Firebird International Raceway and remained in operation until 1997.

In 2005, Bill Compton was inducted to the Arizona Music & Entertainment Hall of Fame.

'We called him Mr. Phoenix'

"Not enough words can be said about the man," Dixon says.

"He had this wonderful ability to represent the hippies and the longhairs — the alternative people of the day."

To Zelisko, what Compton accomplished at KDKB is the gold standard to which every other station should aspire.

"They brought greatness to the masses without considering 'Is this a million-selling album or not?'" he says.

"It didn't matter. Did it fit the set? Was it entertaining to the audience in a way that made that audience come back again and again? And the answer was always 'Yes.'"

To Thompson Smith, his most enduring legacy may be the feeling of community he nurtured among listeners.

"For those of us who lived through that time, I think it was the pride of having a really good radio station in our town," she says.

"Like really good. And just having a go-to station that was your place. That you didn't flip the channel every 10 minutes. You were there for hours. It was your friend. Your radio friend."

It didn't hurt that that's how Compton viewed those listeners.

"I think he thought of the audience as a lot of human beings out there, not just numbers," Manning says.

"People talk about the Voice of God. We called him Mr. Phoenix. It was just because he was, in fact, important. And he carried that importance very well. He wouldn't ever tell you that he was important. But he led a certain portion of the population through a major change. It was true lifestyle radio."

Reach the reporter at [email protected] or 602-444-4495. Follow him on Twitter @EdMasley.

Support local journalism. Subscribe to azcentral.com today.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: How a Phoenix DJ playing what he wanted changed the game at radio