Carlos Santana on Woodstock, women and why he plays 'to get people out of their quicksand'

Ask Carlos Santana to describe his inimitable guitar tone, and the Rock & Roll Hall of Famer doesn’t hesitate.

“My sound is the sound of a woman,” says Santana, 75, adding his current playlist is heavy on Nina Simone, Etta James and the recently departed Tina Turner.

“Some people, like John Coltrane and Wes Montgomery, they sound like men,” he says. “But Miles Davis on his horn and me on my guitar, we sound like women because we got it from the greats like Billie Holiday and Mahalia Jackson.”

It’s fitting then that women play an outsized role in “Carlos,” a new documentary premiering on Saturday at Tribeca Festival in New York, which will be followed by a Santana concert. The movie will have a theatrical release this fall.

While two of Santana’s sisters, Maria Santana Vrionis and Lety Santana, along with wife and frequent drum collaborator Cindy Blackman Santana, all provide context for his improbable journey from Mexican barrio to global rock heights, the biggest presence is that of his late mother, Josefina Barragan de Santana.

“She was my GPS,” Santana says softly, recounting all the times during the heady and drug-filled days of his precocious success in late-'60s San Francisco when his mother’s voice would appear.

“I can still hear her saying, ‘No, that’s not for you,’” he says of parties where cocaine was the elixir of choice. “It helped me say, ‘No, that’s OK, I’m good. I’m already higher than an astronaut’s butt on my own trip.' People looked at me funny, but it guided me.”

From Woodstock to 'Supernatural,' with a winding spiritual journey in between

“Carlos,” directed by Rudy Valdez, takes viewers on a complete tour of Santana’s musical pilgrimage, anchored to reflective narration by its subject and buttressed by vintage concert footage and home video jam sessions.

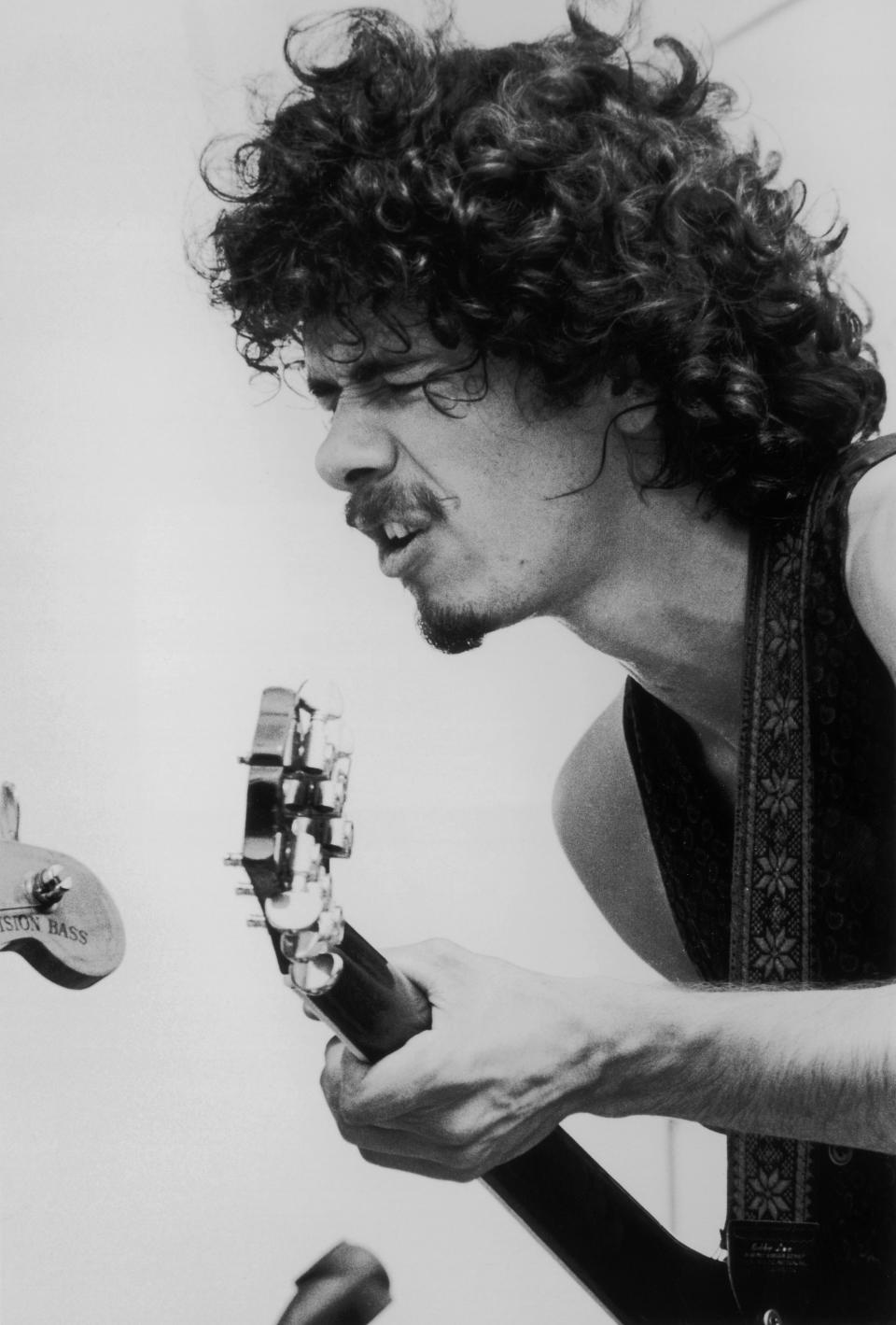

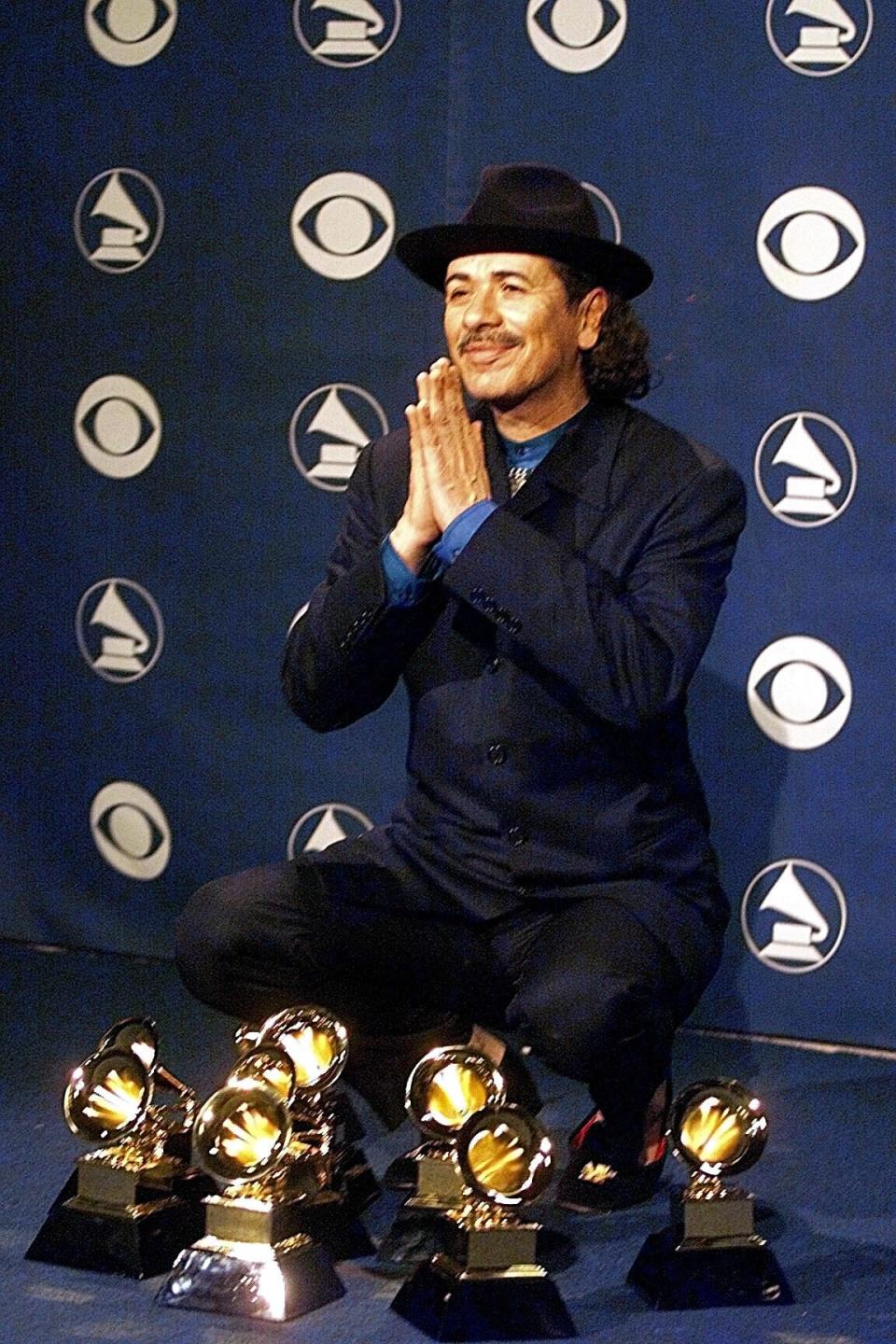

There’s Santana’s meteoric rise (he and his band played the 1969 Woodstock Festival before they even had an album out), transcendent detour (in the ‘70s he followed the teachings of guru Sri Chinmoy), and explosive hit-making return (1999’s “Supernatural” collaboration album equaled Michael Jackson’s eight-Grammy haul for “Thriller”).

Throughout, there were personal challenges as well. They included suffering sexual abuse as a young boy in Mexico (first recounted in his 2014 autobiography, “The Universal Tone”), a divorce from his first wife Deborah Santana (the couple share three adult children), and the 2020 passing of his brother Jorge (who led the band Malo).

What’s made clear in the documentary is music was and remains Santana’s muse, medicine, salvation and purpose.

Santana started out playing the violin under the tutelage of his violin maestro father, Jose, who would enter him in local contests. He sensed something was different from the start.

“I’d put the bow on the violin, hit a note, and people would stop and look,” he says. “It made me realize I had a sound that was beyond my years, beyond where I grew up.”

That sound soon would find its expression through the guitar, as Santana became entranced by the haunting blues sounds of future mentors such as John Lee Hooker.

“I was this young kid from Tijuana (on the border with San Diego) who winds up in San Francisco with tickets to Disneyland rides waiting for me, and those rides were B.B. King, Tito Puente, Eric Clapton, Miles Davis, Jerry Garcia,” he says. “America for me was this vast land of opportunities.”

Santana fused Latin rhythms with guitar-driven rock to create a signature sound

Santana intuitively alchemized tropical Latin rhythms with the emerging blues-rock scene being cultivated by San Francisco promoter Bill Graham, who insisted that the Santana Blues Band, with its 22-year-old frontman, be given a slot at Woodstock despite being nationally unknown. But not for long.

That debut 1969 Santana disc would land months later and feature the instant hit, “Evil Ways.” More big records followed in short order, with soon-to-be classics such as “Black Magic Woman” and his take on the Tito Puente tune, “Oye Como Va.”

But as “Carlos” recounts, financial success eventually caused Santana to double down on imbuing his music with spiritual impact, a quest that he says continues daily.

“Santana’s music assaults the senses,” he says of his songs. “What does that mean? It means you give people chills, they laugh and cry at the same time. The music is there to liberate people from the illusion that we’re not worthy of our own divinity and light.”

With a new tour launching in June, Santana sees no reason to stop delivering his sonic message

Speaking with Santana is an elliptical journey that’s as lyrical as one of his solos.

Speaking of his Cindy, he describes her as being like Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt, with “world-class athlete energy.” Ask if artistry is a gift visited upon the few, he says “there are only two kinds of people in this world, artists and con artists.”

Toward the end of “Carlos,” its subject quietly reflects on being sexually molested as a child, which brought him shame and anger. He says he has journeyed past those emotions.

“I’m not joining the pity party, there’s a way out to the best part of your life that’s a lot brighter,” he says firmly. “And I play music to get people out of their quicksand.”

Santana and his guitar will unfurl that lifeline once again on his new 1001 Rainbows Tour that starts June 21 in Newark, New Jersey, followed by dates in Ohio, Michigan, Maryland and other East Coast cities. The thought of stopping doesn’t cross his mind.

“There’s still more up ahead,” he says. “I am thirsty for adventure.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Carlos Santana doc explores fame, sexual abuse and spirituality