‘He was central to music history’: the forgotten legacy of Leon Russell

Over a decade before he died, Leon Russell began writing a never-completed memoir that highlighted a story of deep humiliation. Upon noticing, at age four, that his genitals looked different from those of his female cousin, the two began to examine each other in a secluded playhouse. That is, until a stern aunt discovered them and, instead of recognizing their play as innocent exploration, proceeded to parade Russell in front of his entire family while accusing him of any number of high crimes and heinous acts. “That incident affected me for my whole life,” wrote Russell, who died in 2016. “I tend to freeze up around any situation that involves people watching me.”

Related: Rock’s best kept secret: Tony King on life with John Lennon, Elton John and Freddie Mercury

How ironic, then, that such a man would wind up, for a certain time, in rock music’s spotlight. During the core years of classic rock – between 1969 and 1973 – Russell was music’s North Star, pioneering a distinctly American sound that changed the career paths of stars, including Eric Clapton, George Harrison and Elton John. In that timeframe, he created a band that became one of music’s most legendary live acts; made Mad Dogs & Englishmen, for Joe Cocker; stole the show from a white hot lineup of artists at the Concert for Bangladesh; became a star in his own right with solo albums that featured songs that became standards, including Song for You and This Masquerade; and inspired the icon Willie Nelson to create his enduring outlaw country persona. Even before he became widely known, Russell had an esteemed career as a first call session pianist, performing with the Wrecking Crew on recordings by everyone from Frank Sinatra to The Beach Boys to the rococo productions of Phil Spector.

Remarkably, he accomplished all this while suffering from what has alternately been described by friends, and by himself, as either bipolar depression, paranoia or Asperger’s syndrome, contributing to crippling bouts of stage fright. “Leon was a deeply insecure guy,” said Bill Janovitz, author of a new book that offers the first holistic study of the musician, titled Leon Russell: The Master of Space and Time’s Journey Through Rock & Roll History. “He struggled with his depressive side his whole life.”

“The way Leon’s mind worked was not like other people’s,” said singer Rita Coolidge, who performed with him on some key projects and who was romantically involved with him for a while. “In every way, Leon was different.”

The darker side of that difference, along with a clutch of other factors, contributed to a fall in Russell’s career as swift and steep as his rise. By his own description, that fall left him “in a ditch by the side of the highway of life”.

The hardships in Russell’s life go back to its very start. He was born with cerebral palsy, causing some paralysis to his right side which resulted in a limp. It made him the target of bullies while growing up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in the 1950s. “He wasn’t a sports guy in this jock-y southern town,” Janovitz said. “He was this nerdy guy with a limp, and big horn-rimmed glasses.”

His father was yet another bully who eventually abandoned the family. At the same time, Russell showed a remarkable facility for music from toddlerhood. By 14, he was playing in local clubs where his band was discovered by Jerry Lee Lewis, who declared him the better piano player and, so, took him and his group on the road. Because of the nerve damage to his right side, Russell had developed a unique playing style that relied on his powerful left hand, helping him create his own rhythms. Other musicians recognized it right away, leading to offers to come to Los Angeles to join its rich session scene. Russell’s piano work held such distinction, it even managed to stand out amid Phil Spector’s cacophonous Wall of Sound productions. According to Janovitz, Russell’s strength as a session guy was “that he could always find a place in the music. Herb Alpert once said that when Leon played, the whole rhythm section would start coming to him,” the author said. “He could change the entire direction or arrangement of a song.”

By 1969, Russell had become a musical octopus with tentacles spreading to his own record company (Shelter Records), a duo he formed called the Asylum Choir, and, most importantly, key contributions to albums by Delaney & Bonnie, the only white act signed to Stax. Their rollicking second album, Accept No Substitute, didn’t sell well yet it became, in Janovitz’s words, “a secret handshake. It was the album where all the major musicians said to each other, ‘You have to hear this.’”

The buzz on Delaney & Bonnie’s record was so intense, it inspired Eric Clapton, Dave Mason and George Harrison to join the group – which also included Rita Coolidge – for a UK tour. A then unknown Elton John found himself equally besotted. “Elton once said to me, ‘I would not be where I am today without Leon Russell and Delaney & Bonnie, and the music you all made,’” Coolidge said.

According to her, the top line of British stars were transfixed by them because, “we had something they didn’t – a mix of southern gospel, rock’n’roll and blues”.

If Russell’s style idealized it, his abilities as an arranger, band leader and songwriter made him the sound’s chief ambassador. “Everybody understood that Leon knew more about music and about the direction we all wanted to go in than we did ourselves,” Coolidge said.

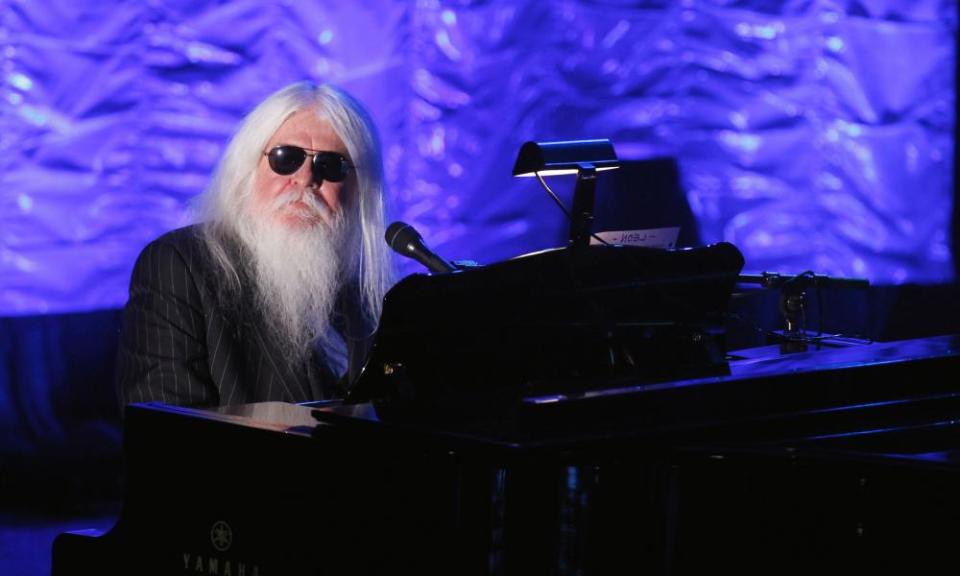

She found herself physically attracted to him as well: “He was such an extraordinary-looking man, with those piercing eyes.” Once they got involved, however, she discovered eccentricities as deep as his talent. “Leon was the most paranoid person I ever met,” she said.

When the pair took the long drive from Memphis to their new home in LA, “he wouldn’t get out of the car. He was so afraid of people looking at him,” he said.

When Coolidge told him she didn’t want to have a baby with him, he insisted on getting a monkey instead. “That monkey terrorized the whole house,” she said, with a laugh. “It was totally untamable.”

As much as Russell flinched from the gaze of outsiders, he loved to create large musical families that he kept close. “As soon as he had any money, he bought a big house and had a bunch of dudes living there,” Janovitz said. “They dubbed it ‘the home for unwed musicians’.”

The most significant family he created was on the Mad Dogs & Englishmen tour, which included nearly 50 singers, players and hangers-on. As musically thrilling as the tour was, it began in panic and ended in chaos. Cocker was fresh off a star-making performance at Woodstock but he didn’t have a band. Hellbent on exploiting his new fame, his mob-connected manager demanded that he tour, threatening physical harm if he didn’t. It fell to Russell to pull together a band pronto, which he did, in part, by taking the players who’d worked with Delaney & Bonnie. Russell didn’t just form the band and write its ecstatic arrangements, he also forged a persona for the show as the ringleader of the circus, decked out in a top hat and Captain America shirt. His look, sound and shtick made him “the ultimate Pentecostal cosmic preacher of rock’n’roll”, said Jesse Lauter, who directed a film, Learning to Live Together, that covered the Mad Dogs’ tour as well as a 2015 tribute concert to it that featured Russell’s final performance. “He was larger-than-life,” Lauter said.

Russell, and the rest of the band, were living large backstage, too. Drugs were a constant, as were orgies, the latter a favorite activity of the band leader’s. Coolidge broke up with him, in part, because of his invitation to have a threesome with him and the famed bassist Carl Radle. The sex at Mad Dogs became so incestuous, said Coolidge, that she would see the band lined up in the hotel lobby in the morning “to get shots because they got VD from all the orgies”.

Fed up with such behavior, Coolidge said she only saw the tour through in deference to Cocker. Another incentive was a solo showcase she had on the tour performing Superstar (The Groupie Song), which she co-wrote with Bonnie Bramlett and Russell. Yet, when the song came out, Russell cut her from the credits. “That was just a deliberate ‘gotcha’ because I’d left him,” she said.

Cocker was even angrier at Russell, who he felt upstaged him. In October 1970, it was Russell who appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone, not Cocker. Worse, due to the cost of the event, Coolidge said Cocker came out of it broke. “He didn’t have a place to live, he didn’t have a guitar. He didn’t have shit,” she said.

Neither Coolidge nor Janovitz believe that Russell intended to hurt Cocker. “To his dying day, Leon was wounded by the accusation of career profiteering from the tour,” Janovitz said. “The fact is Joe needed a band and Leon gave him a great one.”

In fact, Mad Dogs became the template for all the large-scale family bands to come, including Bob Dylan’s sprawling Rolling Thunder tour of 1975, Bruce Springsteen’s big band and the modern Americana group Tedeschi Trucks, who created the Mad Dogs tribute show captured in Lauter’s film. Meanwhile, Russell’s star soared, powered by the pop smash Tightrope, and a hit triple-album concert set, Leon Live that certified him as the biggest concert draw of 1972.

Within three years, however, Russell’s star was on the wane. His music veered from the style that made him popular by moving further into country music and by using drum machines. Also, he had a tendency to believe the wrong people. “If Leon was presented with a good opinion and a bad one, he always went with the bad one,” Janovitz said.

At the same time, his acolyte, Elton John, soared way past him. One of the choices Russell made wound up revealing something profoundly ugly in parts of his audience. He released two pop albums that billed him equally with his new wife, the gifted singer Mary McCreary, who is Black. When the pair toured, hundreds of fans threw nooses on to the stage; some yelled the N-word, which wounded them both. In subsequent years, the pair endured a bitter divorce and while Russell remained productive in the studio, he became ever more remote onstage, reverting to his core insecurities.

Finally, in 2010 Elton came to his rescue, creating a stirring collaboration album with him, The Union, followed by a sold-out arena tour for the two. More, Elton lobbied successfully to get Russell into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Regardless, Russell’s music seldom turns up on classic rock stations today. “Even when I ask active music fans about him, they say, ‘Is that Leon Redbone?’” Janovitz said. “They’re not even sure who he was.”

To the author, that’s a glaring hole. “People love Elton, the Beatles and Clapton but many of them don’t know how important Leon was to all of them,” said Janovitz. “People need to know that Leon was someone central to musical history.”

Leon Russell: The Master of Space and Time’s Journey Through Rock & Roll History is out on 10 March