“Chris and Jon often didn’t get on… I didn’t want to be the leader, but to be a strong voice on the team, brave enough to speak up”: Steve Howe learned to play peacemaker in Yes

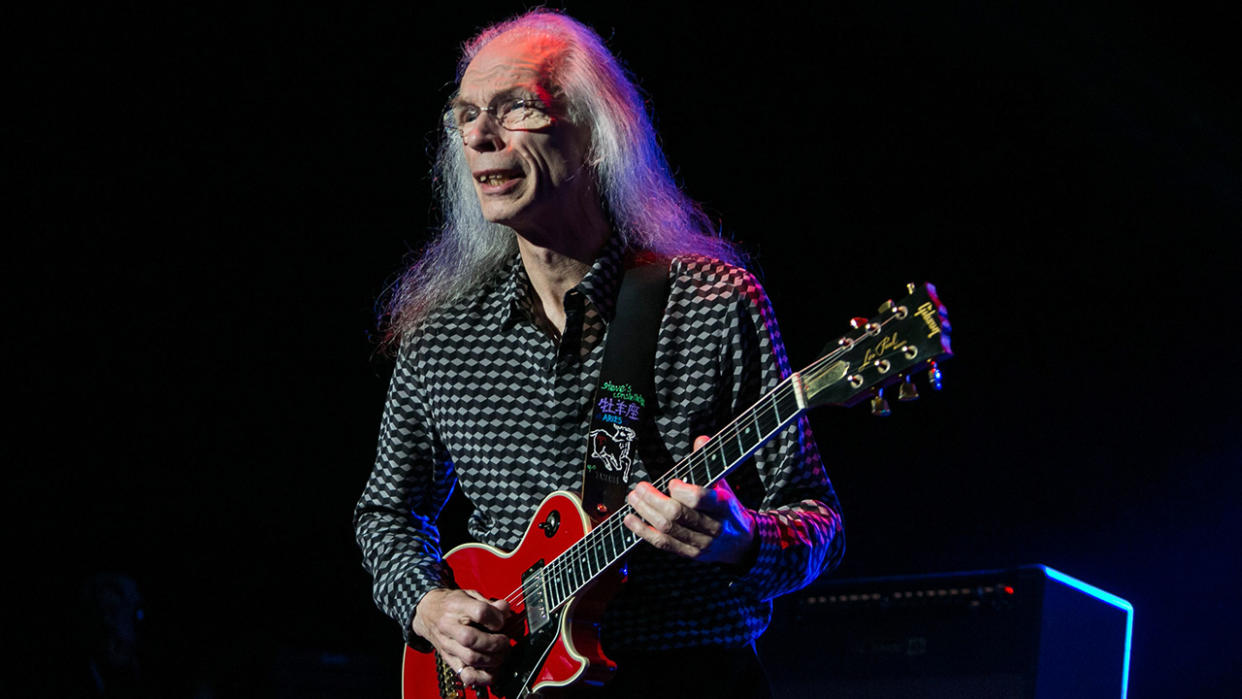

When Prog bestowed the Prog God Award on Yes guitarist Steve Howe in 2018, it was the perfect opportunity to reflect on what he and his various musical projects had achieved over the previous 50 years.

“It’s always nice to get an award, to get commemorated,” says Steve Howe. “Particularly ones that you can only get once, like the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame – and this! Prog God… I mean, it’s a funny title, it kind of makes me smile. It’s a nice moment – thank you so much. I’m going to be in London so I’ll be attending to accept, yes.”

Statistically, Howe must have said the word Yes as often as any of us. As the long-time guitarist with the enduring giants of cosmic rock, Howe has surely merited his place on the Mount Rushmore of prog. He joined the band in 1970, instantly galvanising their sound on the breakthrough The Yes Album and playing a key role throughout their inspired run of music across that decade.

When they briefly dissolved in 1981 after Drama, he enjoyed further success with supergroup Asia, whose 1982 debut was America’s biggest-selling album that year. He moved on to GTR with Steve Hackett, then Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe, which he describes today as “a red-hot band”. In 1990 they were swallowed up by Yes (“a bloody nightmare!”).

After that unwieldy incarnation blew up, he picked up his parallel career of solo and extracurricular work before finding himself again unable to say no to Yes in 1995. He’s been a mainstay with them whenever they’ve been active since, and in this year of their 50th anniversary, he now stands as their longest-serving member. Along the way there have been return visits to Asia, outings with the Steve Howe Trio and multiple other projects.

Howe has always been hungrily busy, from his youthful 60s days with The Syndicats (produced by Joe Meek), psychedelic ravers Tomorrow and Bodast. Even his occasional guest sessions with others reads like a wish list of era-defining music: Lou Reed’s solo debut, Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s Welcome To The Pleasuredome, Queen’s Innuendo. So it’s been a stellar career, and one that continues to move forward apace. He’s presently on a US tour with Yes where, the night before we speak, he’d enjoyed the setting at their Westbury, New York gig.

“It was nice for Yes to be back on a round stage after all these years,” he says. “The one in Phoenix also moves round. We’re blessed with these shows that are reminiscent of some of the best gigs Yes did in the round back in the 70s.”

Does it ever get dizzy for the band on that roundabout?

“Er, not really – it’s down to the mechanics. If it ever jerks, it puts everybody off, so it’s important it’s perfect. There was a very slight buzzing sound last night, but it was only noticeable to us. It was a fantastic gig.”

It’s been a jam-packed year for Howe, Alan White, Geoff Downes, Jon Davison and Billy Sherwood as they’ve marked the Yes half-century with shows and events on both sides of the Atlantic. With the Anderson-Rabin-Wakeman chapter also touring, Yes fans have been spoiled for choice – or, more probably, imploding in an endless grumpy debate as to which outfit is better.

Wisely, Howe swerves any conflict, happier to talk about the music his branch of Yes are making, and reflecting on the band’s past and present of pioneering sounds and roller-coaster regime changes.

“We’re very proud that we have the ability to root through our music and select different sets for consecutive tours, from Close To The Edge to …Topographic Oceans to Drama to you name it. We work pretty hard as we like to cover a lot of Yes’ music and reach those pockets. And we like to keep doing things that might not have been predicted. That’s how we’ve been celebrating the anniversary.

“On this tour we’ve had Tony Kaye on encores, Patrick Moraz is playing with us in Philadelphia [both on keyboards] and [bassist] Trevor Horn’s an occasional onstage visitor. He’ll be performing part of Fly From Here with us, which as you know we’ve reinvented. We always felt it was empowering for us to get Trevor involved again: his presence, in his multiple roles, was important. He has a great history with the band, and it continues.”

Howe recalls his own highly significant history with the band, and early on it involved diplomatically stepping in between Chris Squire and Jon Anderson.

“Most people join a band so they can wear tight trousers and wiggle about. I did it because I wanted to know if I could be a constructive part of a team. When I joined Yes, Chris and Jon… it’s got to be said, they often didn’t get on. They both wanted to run the band. Then I came in, and in a way I said, ‘Well, okay, I’ll run the band then!’ Now none of that went down in that kind of sentence, but I saw two guys squabbling, so I’d say, ‘This guy is right on this.’ And they’d be surprised, but take it. Then another time I’d go, ‘But today that guy is right on that.’ I’d side with the idea, not the person.

“I helped to make the group strong by bringing a balance. It needed it. I didn’t want to be the leader, but to be a strong voice on the team, brave enough to speak up. I wanted to be in the forefront, with enjoyable, serviceable ideas. I didn’t want to rule the world – I just wanted to be part of the story! To be useful, basically…”

Useful he was, as The Yes Album, the first in his golden run with the group, catapulted them to success.

“I mean, Chris and Jon had seen me in other bands. And when I was asked to join, we got along very well… the guys were great. I was amazed by Bill Bruford’s drumming: I’d always seen the drummer as a central figure in any band, and he knocked me out. And so we delivered The Yes Album, and started to collaborate with Eddy Offord, which was a great thing. And they encouraged me to put Clap [Howe’s solo acoustic guitar track] on the album, so I couldn’t have been happier.

“I wouldn’t say it was a piece of cake – we were dependent on income from live shows for a long time. There were periods of struggle. Those first two albums were highly creative and musical, but they hadn’t sold. Fortunately The Yes Album did, and we established ourselves. I think we put the stamp on there that this band was going somewhere and had a story to tell. We had our own sound, which was quirky and risky as hell. We stood out because we were kind of weird… which is a very good thing!”

From there, Yes soared through the 70s with a work ethic that saw them committed to a relentless touring and recording schedule.

“We were self-driven. We had a musical desire to be successful first, but let’s not beat around the bush – we wanted to have nice houses and nice cars too. I mean, it’s not illegal to want those things! And the fact it was an album era and we were an album band gave us a lot of comfort.

“We didn’t need a hit single. Okay, the edited Roundabout set us off well in America – that helped Fragile immensely. But we were trying to be obscure! We were trying to be less commercial, not more. We actually sat down and discussed ‘de-commercialising’ our music, so it didn’t repeat the same old fodder to get on the radio. We just weren’t into that. We were our band, so we did what we did.”

There were those, of course, who reckoned that when Yes started relaying Tales From Topographic Oceans, they took their “de-commercialising” tendencies too far. Yet for many loyal fans, this is when they really got going.

“Obviously if you make a piece of music like The Gates Of Delirium, you’re not kidding yourself that you’re going to be on Radio 1! But this was the joy, the empowerment, that Yes had. It was an anti-establishment idea. We were both of the times and ahead of the times. Relayer was full of our creative impulses, which were something to reckon with. Jon and I had developed such a close, beautiful writing relationship.

“Then that continuous workload for 10 years was partly created by managers and agents who wanted their buck. It got a bit out of control. But I can’t complain – you’re rarely going to be successful without people like that in your career, so you’d better get used to it!

“To our credit, we were capable of living up to the expectations of this fast-moving schedule – and to the artistic ones. We carried on, kept building. I mean, how hilarious is it that Bill [Bruford] left after Close To The Edge because he thought it was too commercial? [Laughs] We put the music first. Kept pushing on to the next story, the next era. The next album was always the most exciting one to us.”

Howe muses over Tormato getting “tonally difficult” and clarifies that the band had got “differing needs” by that point. “To me, it signalled problems. It became a bumpy road.”

But then Yes “discovered Trevor Horn and Geoff Downes, and developed Yes to go on again. Drama sits awfully well with me. I love that album, I’ll admit it, even if I’m not always sure who’s playing what on it…”

He later expresses his fondness for the studio tracks on 1996’s Keys To Ascension, which marked his third time of joining Yes. After the 1981 split, though, which he partly puts down to British audiences “undermining us” by showing unkindness to Horn, he’d moved out to conquer separate terrain. He teamed up with Downes, Carl Palmer and John Wetton for Asia, which swiftly grew to be almost as big as the continent. “John and Geoff started writing all these great songs together, and Geoff and I had musical chemistry, sparring off each other. That first album was bloody great.”

The bumpy road remained bumpy. “The 80s was about a loss of continuity. So you’d do something great, then not. Then something great again, then something not great. A win-lose-win-lose time. The second Asia album was… a mixed bag. GTR came together, did a nice tour, but became fragmented. And then Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe comes along, and the one album we do is pretty amazing. Great, we’ve established ourselves as a whole new entity to Yes. But no! Suddenly somebody in the band, or their manager, reckons it’ll be better to call it Yes. And that was the beginning of the end.

“We were just a great little band called ABWH – we could take on anybody! It felt like being in Tomorrow again! But it was all sacrificed, all taken to the slaughter – to quote a Yes song from Drama – because apparently we had to be Yes again. And at that time there was nothing there. No heart and soul. There were too many people, lawyers, accountants, drivers, pension schemes. It was a bloody nightmare!

“After that I popped back to Asia, and did more solo shows, and thought I was the new Chet Atkins… Then lo and behold, ’95, Yes invite me back, and this time it feels nice, like it had done before. I started to enjoy that we had years and years of credibility. From there Yes just kept on reinventing itself… We’ve got an awful lot to live up to now – you can’t rest on your laurels.”

And so Yes cruise – sometimes literally – into their second half?century. And let’s not forget that Howe had an intriguing career even before joining that journey. The Holloway-born Devon resident joined The Syndicats at 17, then moved on to The In-Crowd, whose singer Keith West made the cult classic Excerpt From A Teenage Opera. Morphing into Tomorrow, they had a hit with My White Bicycle and were hepcats on the UFO underground scene, playing with Pink Floyd, Soft Machine and Hendrix before splitting in 1968. Howe then joined Bodast, who appeared set up with a US record deal and an album produced by Keith West, but the record got shelved (until Howe excavated it years later). Some of Howe’s music and riffs for Bodast songs turned up in reimagined forms with Yes.

“America were chomping at the bit for Bodast, but the label closed and the album got buried, which was so depressing. When I joined Yes I figured that music, which I’d worked hard on, was never going to come out. So yes, there are at least three references to it in Yes music, most notably Würm in Starship Trooper, and if you listen closely, there are bits in Close To The Edge. I won’t hide good stuff away – it served us well and had another life. A twist of fate.”

And is it true that as part of Tomorrow, you did the first ever John Peel session? “I believe so. He took a shine to us – that psychedelic scene was really happening at the UFO. People were tuning in to that. Tomorrow was the first band where I felt we had a powerful, confident ego, where we believed in ourselves. We felt we could stand up to more or less anyone – Hendrix, Floyd, we’ll do it!

“We weren’t shy. It was very enjoyable. And great training. We even appeared in that film Smashing Time [a 1967 British comedy], where we’re in, of all things, a cream pie fight. I think my one line was, ‘Get him!’ That didn’t do us much good though!”

Howe’s other work across the decades, documented on the two consummately curated Anthology collections, ranges from solo albums (from 1975’s near-classic Beginnings to 2011’s Time) to music with the Steve Howe Trio, featuring son Dylan (who’s also played with Yes) on drums. Of course, there’s also last year’s Nexus album, which documented a collaboration with his son Virgil, who tragically died shortly before its release. “He wrote most of it, and I coloured it,” Steve says. “Basically I’m going to love that record forever. Bless his dear heart.”

As for those fruitful guest sessions with Queen, Lou Reed et al, Howe is “proud to have been versatile. That’s why I loved Chet Atkins – he cut across. I always wanted to mix up Chet, Wes Montgomery, flamenco, [Andrés] Segovia… which was a big ask, and somehow I morphed into a cross-bred guitarist. If you can’t do sessions, you’re not a very good musician. You should revel in the challenge.

“I have no idea how Rick [Wakeman] and I got asked to do Lou [Reed]’s debut solo album, except that we were in the same studio, at Morgan in Willesden. Thing is, he did it right: played us the demos and said: ‘Go out there and do them better than this.’

“As for Queen’s Innuendo, only David Bowie and myself – I say humbly – have ever been invited to play with Queen. Quite a privilege. And some people think it’s amazing that I’m on Frankie Goes To Hollywood. It means people’s expectations of me shift. Anything that surprises people and brings them in is great. It hopefully leads to them exploring the whole landscape of Yes and all my music.”

There’s no doubt it’s been a curveball career as dazzling and unpredictable as a Howe guitar line. What keeps him going strong at 71? His schedule with Yes and others would be enough to exhaust a man half that age. Is there a secret to surviving and thriving?

“Well, it’d take a long time to fully explain. One thing which surprises me is how much I still dearly love the guitar. But the fact that I’ve got energy and determination and some clarity, and I’m still prepared to make sacrifices, that’s got more to do with learning to make better decisions.

“When I went vegetarian in 1972, and then when I started meditating [Transcendental Meditation] in 1983, those two points have made a far more profound difference to my life than, y’know, what car I drive or what clothes I wear or how my haircut is!

“I allowed those decisions to make change. I wasn’t bothered if people sneered or joked back then. I called bullshit. Basically, me, [wife] Jan and my family decided we were going to live our lives the way we wanted to, while hopefully not upsetting anybody else.

“We’re not radicals, we’re not extremists. All we want is to pick a healthy, loving life. Now, certainly I can be pleased that I’m fit and slim and healthy and fairly sensible, but I don’t like to take anything for granted. Every day you need to take steps to make your life good.

“It’s not a case of you do one thing and you’re the luckiest guy in the world. You have to not let yourself down. My regular patterns and routines, my concern about the food I eat and the non-pharmaceutical things I prefer – these choices empower me, giving me energy and clarity. If I hadn’t made those decisions, I wouldn’t be here…

“Oh, I don’t mean I wouldn’t be on the Earth! I mean, you wouldn’t be talking to me as the long?term guitarist of Yes. I wouldn’t have done that so well. Maybe I wouldn’t have been able to bounce back so many times, or I’d have taken greater offence at things people connected to me have done, all that stuff.

“So very generally – look after yourself. Doctors and hospitals look after you when you’re sick, but it’s much better to avoid getting sick in the first place. Keep yourself on that plane, that level, every day. That’s what I’ve learned. Not long before he died, my dad, who was a master chef, told me he loved his routines. Said they were his channel, his route through life. So that taught me: don’t knock routine if it makes your life run smoother.

“Same with music, though I’m not an arduous practiser – I don’t need to like you do in your first 10 years. What I do is play, not practise. Find new things, improvise, muck about. And I explore an array of textures, a family of guitars – steel, acoustic, electric, Spanish, 12-string. I wasn’t just hearing Hank or Duane when I started, or any one style: I was happier with a multifaceted approach. I was hearing a different drumbeat… except on guitar!”

Steve Howe, Prog God: forever marching to his own guitar sounds.