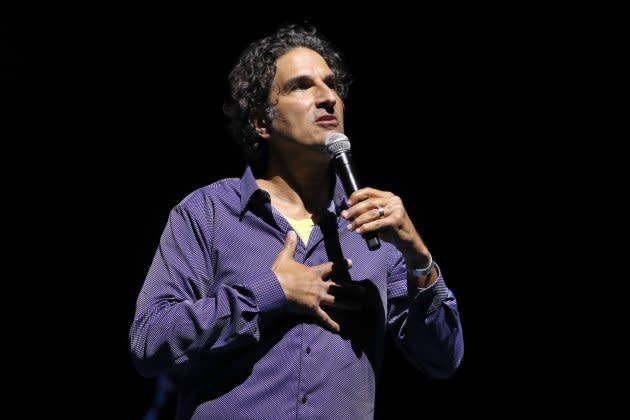

Comedian Gary Gulman Reveals the Time He Hit Rock Bottom

Some people skip the intro. I don’t trust them. It makes me wonder where else they cut corners, where else they’re phoning it in, what other flimflammery they’re perpetrating. If you didn’t read the intro, you didn’t honestly finish the book. Saying you read a book but didn’t read the intro is like saying you shoveled my driveway, but you left two feet of snow on the walkway. Or saying you took me out to dinner but let me leave the tip. I’ve been reading intros, forewords, and preambles since before I knew how to pronounce preface. You should always read the intro. “But what if I get four paragraphs in and the book seems like a downer?” Friend, you are reading this because either:

You’re familiar with my stand-up work.

If so, I believe I’ve generated some goodwill with you, and I promise not to squander it. Over the length of this book, I will entertain you in the way that you have grown accustomed. But first I need to take a couple of pages to let you know how bad things were when I started examining the events I recount herein.

More from Rolling Stone

'Jewish Space Lasers' Takes You on a Mindblowing Trip Into Conspiracy Madness

Hasan Minhaj Still 'One of Three' Finalists to Host 'Daily Show' After Bombshell New Yorker Story

Or,

B. You bought it based on the celebrity endorsements.

a. Shame on you.

b. You’ll have to trust the fact that the people on the back cover wouldn’t blurb some slapdash cash grab from a virtual unknown.

Now, at the very least you have an idea of the tone of this tome and are impressed by how deftly I deployed the Modern Language Association outlining format that I’ve retained since ninth-grade English, Mr. Crean. So, I’m going to return behind the fourth wall because this jaunty device, if not used judiciously, can come off cloying.

On a white-gray Thursday in March 2017, I was on my way to a 1:00 p.m. appointment with my psychiatrist. I was running late, the only running I could manage anymore. I was sick with worry and contempt for myself. Maybe he had another appointment, a more important one, right after me. Maybe I wouldn’t get to see him at all. I didn’t think I could survive a postponement. These meetings were the only thing I looked forward to, the only time I felt safe, during weeks of relentless misery. You lazy, pathetic, worthless zombie. It’s not like 1:00 p.m. is early. People are halfway done with work. High school kids have one class left. If it were the day before Thanksgiving, first graders would be home by now.

I was forty-six and living in midtown Manhattan with my girlfriend, now wife, Sadé. (Not that Sadé.) We’d been together for two and a half years. The first six months were perfect. Bliss. For the past two years, a sinister third wheel had joined: crippling depression and anxiety. That week, I had been to the emergency room twice within three days because I needed to be separated from spaces that contained anything I could use to harm myself. I felt guilty over how exhausting it was to care about and for me and regularly begged her to leave me. Maybe because I had been so damned delightful for our first 180 days, she had refused. More likely, and this was impossible to believe at the time, she loved me.

My anxiety was relentless. When I was awake, I was in agony, most intensely the moment after I woke and Oh yeah, my life is in shambles, I’m running out of money, and I hate myself flooded back into my consciousness. Then I’d walk our two Cavalier King Charles spaniels up Fifty-Sixth Street, to Lexington Avenue, right onto Fifty-Seventh Street, to Second Avenue, and then back to my apartment. A walk around the block; yet my feebleness dragged it out to twenty minutes. I shuffled about, grinding my teeth, chewing my bottom lip bloody, thinking about all the things I needed to do today but would procrastinate, then beat myself up for putting off. Just a couple of years before, I ran thirty miles a week. Now a two-tenths of a mile crawl drained me. I’d feed the pups, eat a giant bowl of Ezekiel golden flax cereal covered in maple syrup and almond milk, then go back to sleep until the dogs wanted another walk. When I wasn’t asleep, I was catatonic while my brain attacked every weak point in itself, attempting to criticize me into submission.

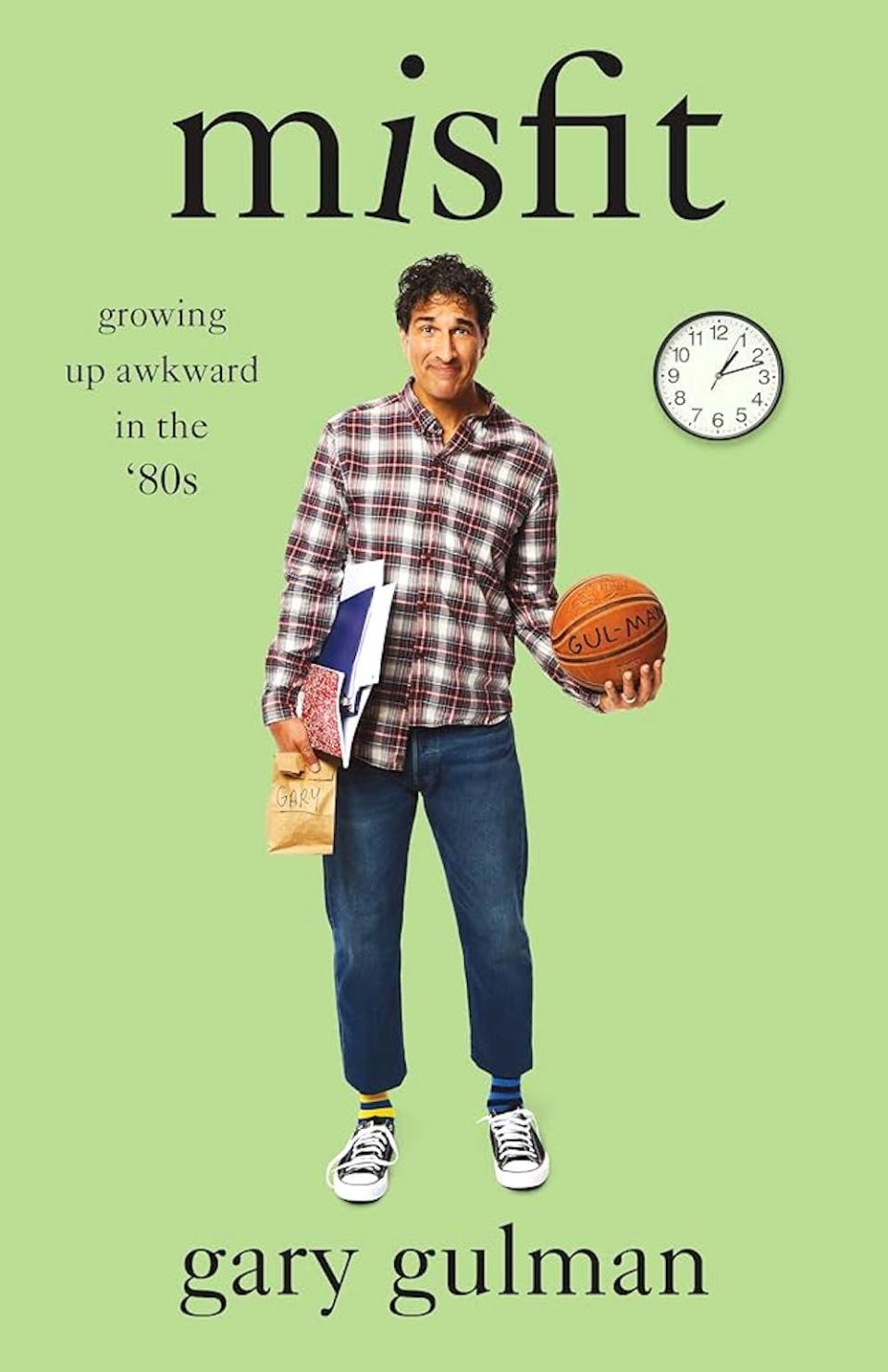

Order Misfit: Growing Up Awkward in the ’80s

I was finding it nearly impossible to do stand-up comedy, the only job I’d held since December 24, 1998. A job I’d started dreaming of and practicing in my bedroom in kindergarten. My brain insisted I was inept at it and getting worse. I had saved up enough money to not work for a year while I found a different job, an easier job. Easier than a job I could wear jeans and a Super Grover T-shirt to, make my own schedule, and took up only an hour of my day.

My lease was ending, and I didn’t have the energy to hunt for a new apartment. I didn’t have the energy to shower standing up. Never mind that my new place would have to be far cheaper and allow two dogs. Never mind that I heard that moving is nearly as stressful as the death of a family member and I prayed all my waking hours that I was that family member.

When I tried to think of reasons to continue, the best I could come up with was my desire to see how season three of AMC’s Better Call Saul, the ingenious prequel to the ingenious Breaking Bad, would end. But even that masterpiece didn’t always provide sufficient motivation for me to keep producing my own mordant drama.

Late one night I had pulled a plastic bag from the box a toaster came in over my head in an impulsive attempt at a painless exit. But it occurred to me, as my head emerged from the top, that this was not a plastic bag but a plastic sleeve. Funny.

Later that same week, in a furnished apartment on a rare trip out of town to perform in Denver, I removed the carving knife from the kitchen’s wooden knife block and held it against my wrists. Then I pictured the person who’d have to clean up on Monday and gave myself an excuse to refrain from ending things that way. I wanted to stop feeling like this, even if I had to die.

Throughout this Bedlam, monthly visits to my psychiatrist, Dr. Richard Friedman, were half-hour capsules of hope. He never gave up, never ran out of ideas, treatments, or offers to admit me into the hospital.

There isn’t a subway that goes directly to his office at Sixty-eighth and First-ish, and I didn’t have the brain function to figure out the bus combination that would get us there on time. What about Uber? I had resisted Uber for years. I didn’t feel safe riding with regulated, licensed, experienced New York cabdrivers. I’m just going to get in the back of a stranger’s black Camry? Not yet. A cab? Out of the question. I was not going to be able to work anymore. Until I found a new job, paying twenty dollars for a ride to a building I could walk to in twenty-six minutes seemed reckless. But we were running late. Depressives, as well as the angels committed to dragging them through life, are late for everything. Just to leave the house we need to overcome standard inertia compounded by the weight of a boulder of resistance in our minds.

Sadé had furthered our delay with a last-minute shoe change. She decided to put on a sturdier shoe, Doc Martens boots, calf-high, in magenta. I loved that my partner wore combat boots. Made me feel vicariously punk or emo. I’d been too timid to join in the august grunge era, so her bold Docs felt like consolation. This was going to make us even later. Unless . . .

We slid into a cab going across town at East Fifty-Seventh and Second. I never took my eyes off the meter as it soared, eating into my financial parachute at a sickening speed. It was already up to eleven dollars when we cut over around Sixty-Fourth Street and Third. Then the driver stopped short. Gridlock. The meter slowed as the dashboard clock raced.

We had fifteen minutes to get there. We weren’t moving. And we would still have to wait for the fickle elevator to the eleventh floor. Sometimes there’s a gurney or two squeezing the capacity further. Stairs? Eleven floors, dragging my boulder the whole way. Not today.

I started crying. Not gently rolling tears. I was heaving with sorrow. I felt guilty about crying in front of Sadé but more so the cabdriver. If anyone should be crying, it’s him. Here I am sobbing and I’m not even working a day job—never mind one that requires navigating the worst traffic on the planet in a seat with such flimsy lumbar support. Hopefully, because of our destination, he thought I was dying. I was dying, just not in the way I hoped he thought I was.

We had ten minutes to get there. The Google map said we’d need fifteen minutes to walk. And then the elevator packed with incoming wounded would delay us five minutes more. A thirty-minute session could be cut to ten. What if it took me that long to tell him how dreadful I felt? How sad, desperate, discouraged, unsafe. What if we had to reschedule for next week or further out? People vacation in March.

A decisive Sadé said to the driver, “We need to get out here,” and handed him twenty dollars. This exceeded my 30 percent tip policy by dollars, but psychiatrists’ meters rise in higher increments. If we were going to salvage a useful portion of the session, we’d have to accelerate our pace.

We got out of the cab and Sadé sprinted. For the past two years she’d had to shuffle alongside me to match my geriatric tempo. But in an instant, she was fast, supremely athletic. The sidewalks were crowded. Charging suit-and-tie men and pantsuit women swarmed the block. An elderly woman in a floral-print blouse and black pleated slacks walking a shabby gray schnauzer was walking toward us, just two strides from the galloping Sadé. Oy vey. Either the biddy or the hound would be trampled ’neath Beetle Bailey’s hooves. That will warrant a pause in our dash if not a 911 call. I’m screwed.

And then, before you could say Jack Be Nimble, Sadé hurdled the schnauzer. I laughed out loud, reflexively at Gail Devers in jackboots. For months I’d been begging her to leave me. “Save yourself,” I implored. Then she Super Mario-ed that scraggly pooch and scrubbed my plan. That leap made me so grateful.

We arrived fifteen minutes late. Dr. Friedman waved off my apologies. Such grace.

In a half hour we came up with a plan. We decided that I needed time away from the city and its intrinsic anxiety and landlord’s bills. I’d be able to save money while I regrouped and changed careers. I’d move back into my mother’s house, the place where I had grown up. The place I liked to visit. For limited stints. Knowing in four hours I could be back in Manhattan. Sadé would stay behind and move in with some New York friends.

On June 26, 2017, Sadé and I packed up the apartment and put it in storage. An act of hope, or possibly, delusion. In 2006 in Los Angeles I put an apartment in storage before a planned six-month experiment in Manhattan. A year later, during a separate episode of depression, I decided to remain in New York City and gave everything away to a friend of a friend. If you stand close enough to one-bedroom-accommodating storage units you can feel the despair through the corrugated garage doors.

Moving is stressful even for the highly functioning; for the acutely depressed it is torture. A harrowing gauntlet of fear, stress, and hard labor. We had loaded our one bedroom into a fifteen-foot U-Haul truck, a behemoth of a freighter I still can’t believe they breezily rented to a middle-aged Jew. We brought most of the furniture to the storage unit, then I drove four hours to Massachusetts, carting the four huge boxes that wouldn’t fit in storage, to my mom’s house. I got to her house after midnight and brought in my suitcases and backpack. I stood in the center of the cubicle I’d occupy until I was well enough to get back to life. I had first slept there in a crib.

During the previous two years, I’d checked myself into the psychiatric ward on two separate occasions about a year apart. For most that would be considered a firm bottom. This felt much lower. I find it easier to tell people that I’d been in the psych ward than to tell them that at forty-six I moved back in with my mother. Still, as I consider my journey out of that room, I can’t say that my return was inconceivable. The worldview I developed in that house all but ensured the conditions that brought about my return. Now I was counting on it to provide the temporary refuge I needed to fly away, for good this time.

EXCERPTED FROM MISFIT: GROWING UP AWKWARD IN THE ‘80S. COPYRIGHT ? 2023 BY GARY GULMAN. EXCERPTED BY PERMISSION OF FLATIRON BOOKS, A DIVISION OF MACMILLAN PUBLISHERS. NO PART OF THIS EXCERPT MAY BE REPRODUCED OR REPRINTED WITHOUT PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHER.

Best of Rolling Stone