Coronavirus listening: Finding comfort in the California sounds of '70s soft rock

During a moment in which the ability to remain calm is disconcertingly connected to the size of your Purell and paper towel stockpile, the sanitized pop sounds of 1970s Southern California can project an inherent comfort. Who needs musical aggression, after all, when there's a relentless, invisible enemy lurking outside your window?

The Grammy-nominated Los Angeles imprint Omnivore couldn't have foreseen the coming COVID-19 coronavirus when it commissioned a trio of soft-ish rock releases by America, Andrew Gold and the Righteous Bros.' Bobby Hatfield, but the timing couldn't be better for their release. Crazy times require non-crazy music.

Sanity permeates Hatfield's "Stay with Me: The Richard Perry Sessions." Recorded after the end of the Righteous Bros.' run of hits (most famously "Unchained Melody" and "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'"), the collection gathers extant recordings he made with famed Los Angeles producer Richard Perry.

Perry, whose early production credits include Captain Beefheart's "Safe As Milk," Tiny Tim's "God Bless Tiny Tim" and Harry Nilsson's "Nilsson Schmilsson," liked to add flair to his production. The first few measures of "Stay with Me" don't hint at the barrage to come: a stress-free guitar-and-keyboard duet glides in, courtesy of Al Kooper, as Hatfield's soaring, soulful tenor delivers a series of questions: "Where did you go when things went wrong, baby? Who did you run to and find a shoulder to lay your head upon? Wasn't I there and didn't I take good care of you?"

Apparently not, because Hatfield's singing this song as if his very existence depended on her, and she's got nothing to say. When the brass and full band kick in, sound roars from the speakers. (One clue on why she might have left comes in a later verse, when he insults her by singing, "Maybe I was too good to you," but whatever.)

Does the drummed rhythm of "Oo Wee Baby, I Love You" sound like the one in the Beatles' "Get Back"? Absolutely. That's because Ringo Starr does the pounding across the "Stay With Me" sessions, alongside Klaus Voorman (bass), Kooper (keyboards and guitar), Rolling Stones saxophonist Bobby Keys and more. In fact, at times "Stay with Me" is too hard to be a soft-rock record. But when it does move to gentleness, it's with purpose: Hatfield's take on Cole Porter's "In the Still of the Night" feels designed for quarantine comfort.

Best known for hits such as "A Horse with No Name," "Ventura Highway" and "Tin Man," the Los Angeles band America is an archetype of Southern California musical tranquility. With harmonies that soar like seagulls and a country-tinged twang that suggests wide open space, the trio was one of the most successful (and critically dismissed) bands of the early 1970s.

Nearly a half-century later, many of the previously unissued demos and takes on "Heritage II: Demos/Alternate Takes 1971-1976" hit with a certain weirdness. Since they weren't recorded for release, odd accents such as use of ARP 2600 synthesizer on the "Mandy" demo adds a surreality. The outtake of "Tin Man" is a revelation. As with the hit version, this one employed longtime Beatles studio-dwellers producer George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick. But this one strips away all of the singing save the backing vocals. The effect reveals the nuance beneath the singing — and makes it a hot pick for your next stuck-at-home karaoke session.

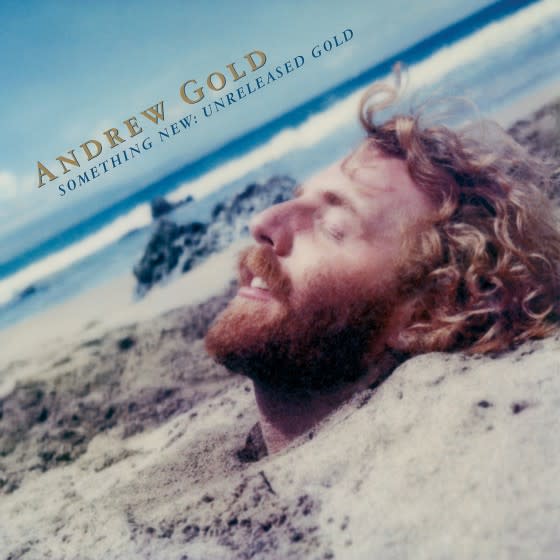

The Burbank-born Gold, who played on some of America's sessions over the years, was the son of Oscar-nominated composer Ernest Gold and landed two smash middle-of-the-road hits in the 1970s: "Lonely Boy" and "Thank You for Being a Friend." A prodigious instrumentalist, he played with Cher, Bonnie Raitt, the Eagles, Linda Ronstadt, Jackson Browne and dozens more before he died in 2011.

The stuff on Gold's "Something New: Unreleased Gold" rolls with Beatle-esque ease and sounds like Father John Misty minus the irony. A songwriter whose appreciation for a seamless pop song suggests a kinship with classicists such as Billy Joel, Randy Newman and Adam Schlesinger, Gold loved a good melody as much as he loved a hook, and these stripped-down versions reveal a writer who understood how to structurally engineer a song.