"The curtain across the control room went back and there was Rick with his dick in a wine glass going, 'Coq au vin, anyone?'." David Paton's life in music

Fomer Bay City Roller, founder of Pilot and member of The Alan Parson's Project, David Paton has also worked with Kate Bush, Camel, Jimmy Page, Rick Wakeman and Fish, to name but a few. When he released his new autobiography Magic: The David Paton Story in 2023 Prog just had to sit down for a chat with the man.

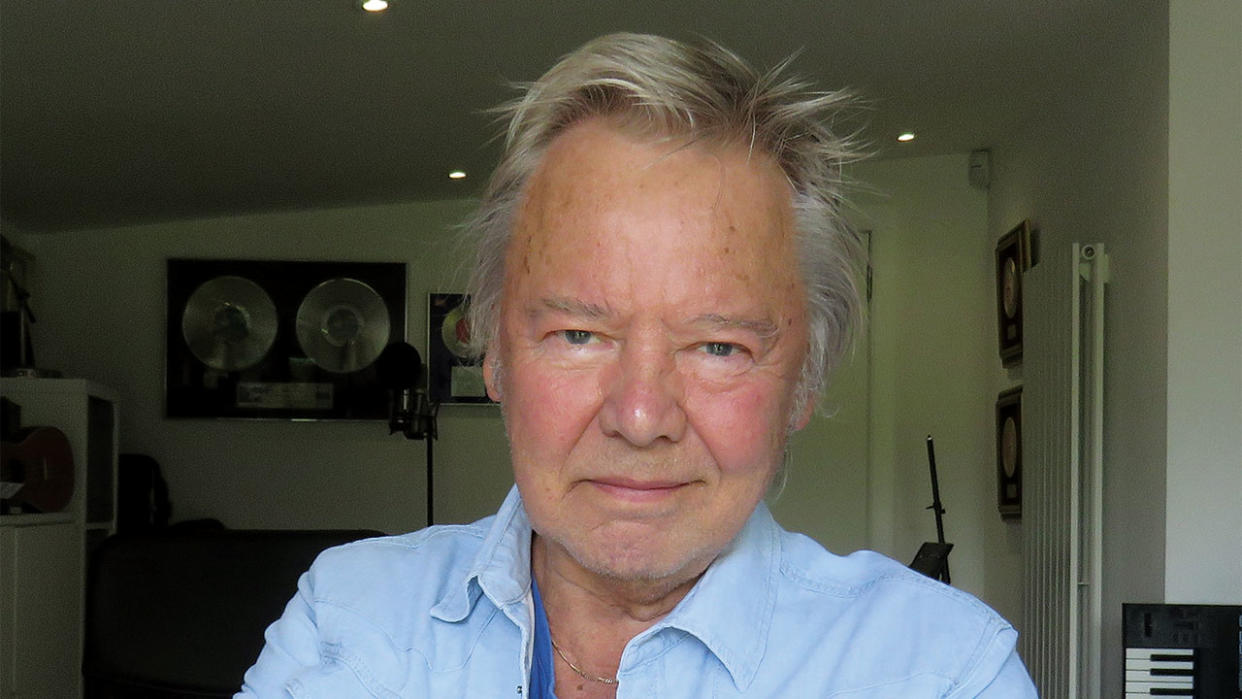

Edinburgh-born singer, bassist and guitarist David Paton has played on countless great records throughout his career. First striking gold as the voice and writer of Pilot’s 70s power-pop smashes Magic and January, he went on to work with The Alan Parsons Project, Kate Bush, Camel, Rick Wakeman, Fish, The Pretenders and more. Paton has played Scalextric with Paul McCartney, performed at Live Aid with Elton John, and once politely declined to join a surgeon in an impromptu rendition of Magic while having a tiny camera inserted into his urethra. Now 73, but still remarkably well-preserved, he’s just written his star-studded autobiography Magic: The David Paton Story.

Why publish your memoir now?

I found myself relating stories about my career at dinner parties and friends and family said, “Why don’t you put them in a book?” I started 20 years ago and eventually got up to 60,000 words.

Pilot songs January and Magic never seem to get old. Are they the gift that keeps on giving?

Even now, Magic still gets used for so many things. In the US the manufacturers of the drug Ozempic have been using it to spearhead their campaign since 2018. It’s a diabetes drug, but one of the side-effects is weight loss, so the Kardashians are [allegedly] using it!

You made nine albums with The Alan Parsons Project…

Eye In The Sky was probably the pinnacle. Everybody was really focused and after that we seemed to wane a bit because Eric [Woolfson, APP pianist] wasn’t writing songs of the same quality. He had a fall out with [record industry bigwig] Clive Davis and that was reflected in his writing. A few of the songs had a dig at Clive and I found it petty.

Which of the songs that you sang with APP is your favourite?

Maybe Children Of The Moon. It was very difficult to sing, and in those days you couldn’t tweak it after the event. You had to do it until it was perfectly in tune and perfectly in time, but Alan was brilliant to work with on vocals – he made you a perfectionist.

Your book expresses disappointment that the 1993 to 2013-era concerts by The Alan Parsons Live Project didn’t involve any original members other than Alan…

Yes, because that cheats the public. They think they’re going to hear The Alan Parsons Project, but they’re actually seeing Alan miming to a piano part. Alan’s not an accomplished singer, and his musicianship is not accomplished either. The Project was Eric, Ian Bairnson [guitar], Stuart Elliott [drums] and myself, and Eric is no longer with us. We created that sound and it can’t be recreated without us. But Alan would dispute that, of course.

What were your thoughts when you first met Kate Bush at Air Studios in 1977 to begin work on The Kick Inside?

I’d already worked with a lot of good songwriters, but Kate was brilliantly talented and we all saw it immediately. She was an English rose, an angel… totally fantastic in every way.

Your bass part on Them Heavy People is wonderful.

Thanks. If the song is great, you get inspired. I loved the reggae feel so to have a chance to express myself like that was a thrill.

Were you pleased to see Kate top the charts again recently?

Absolutely. I wasn’t involved in Running Up The Hill, but it’s something I could listen to over and over and it was great to see a younger audience grasp the importance of what she does. After playing on The Kick Inside and Lionheart I watched Kate’s career blossom and I bought each new album as it came out. I loved stuff like And Dream Of Sheep.

You worked with Jimmy Page on his soundtrack for Death Wish II. Was that daunting?

Yeah! I love his guitar playing, but Jimmy couldn’t have been more welcoming or enthusiastic. I remember he had no qualms about putting down his parts in front of the rest of us. Some artists can get a bit precious and ask the other musicians to leave the room, but not him. One night he took us for a Chinese meal and just wanted to talk about who we had worked with. He didn’t want to talk about himself.

Funny that, when singing your praises to Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell, Jimmy described you as a guy “from The Bay City Rollers”!

I know! Of all the things. That brief time I spent in The Rollers is the bane of my life. They were everything I was against, really. Even in Pilot we grew moustaches to rebel against the teenybop thing we’d been categorised as. We wanted to show we could play.

Which musician brought out the best in you?

That’s tough. But Rick Wakeman gave me a lot of scope to do what I wanted. I didn’t have to follow the parts on the records.

And a few laughs with Rick, no doubt?

He was funny all the time. I first worked with him on Time Machine. I forget which song we recorded first, but he said, “I’ll just leave you to it,” and I was a little worried because of all the time signature changes. Next thing the curtain across the control room went back and there was Rick with his dick in a wine glass going, “Coq au vin, anyone?” That certainly broke the ice…

Clairvoyance is a theme running through your book. You believe in it, then?

Yes, I was brought up with it. My grandparents would have séances on a Sunday afternoon and my dad felt a very powerful connection with the spirit world, but didn’t think it was right to use it.

What’s left for you to achieve?

Maybe I’ve retired too early, but I see the book as full-circle. I have a good family life and I try to stay fit. I remember Clint Eastwood saying, “It’s important not to let the old man in.” It’s good advice.