David Bowie: curator, mentor, nurturer, counter-intuitive collaborator, hard rock lover, surfer of the zeitgeist, Tin Machine genius

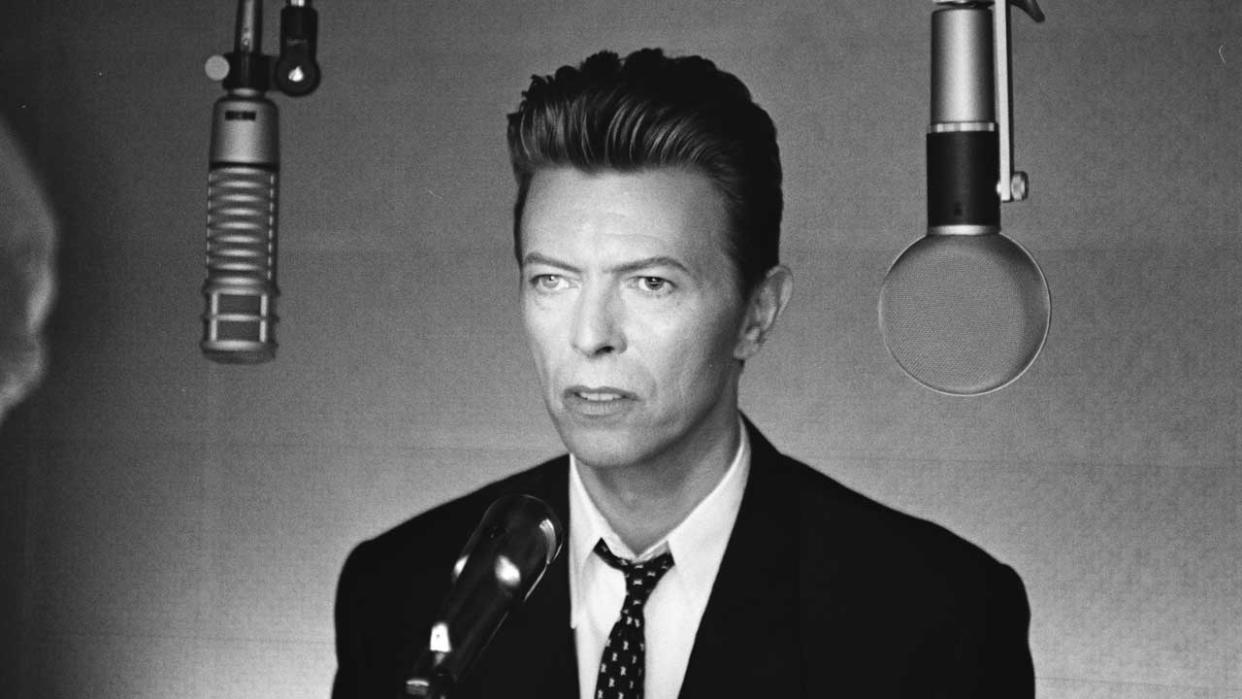

I spent one extraordinary day with David Bowie in London. The year was 1993, about halfway between Ziggy Stardust and Blackstar. He was 46, a slightly built, lightly tanned, fabulously good-looking man who chain-smoked with the decadent nonchalance of a bygone era.

Our mission was to spend a day visiting his old London haunts of the 1960s and 70s on a trawl for memories and meanings. We went to the premises that once housed Trident Studios in Soho where he recorded the albums Hunky Dory (1971), The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars (1972) and most of Aladdin Sane (1973).

We went out to the East End where he played his first gigs at pubs such as the Bricklayers Arms, the Green Man and the Thomas A Becket. We went to Heddon Street in the West End where he was photographed with his foot up on a rubbish bin underneath a sign that read ‘K. West’ – the iconic image on the inside cover of the Ziggy Stardust album.

We went to the Marquee in Wardour Street and to Hammersmith Odeon (since renamed Apollo) where we sat together on the stage, in the freezing cold of a winter afternoon, and Bowie recited verbatim the words that he spoke from the same stage in July 1973 on the last night of the Ziggy Stardust tour: “This show will stay the longest in our memories, not just because it is the end of the tour but because it is the last show we’ll ever do.”

In the aftermath of Bowie's sudden and unexpected death on January 10, 2016, I thought long and hard about that magical day we spent together. It was one of the most untypical celebrity encounters I can recall.

There was no PR minder or other intermediaries. Bowie had not merely agreed to be interviewed. He picked me up in a car with his own driver which ferried us around an itinerary which he had planned and mapped out. He had dug out old diaries and notebooks from the period, which we pored over afterwards in a nearby hotel over peacock soup and a cheese sandwich. And, while I wrote the resulting story (for Rolling Stone magazine), there was a sense in which he had helped to sculpt it on my behalf.

Bowie was a very emotional man. It was one of the reasons he adopted so many fabulous and remote personas – Ziggy, Aladdin, the Thin White Duke, the Man Who Fell To Earth, the singer in Tin Machine. Along with the drink and drugs, these roles were a way of camouflaging his feelings and distancing his true self from his art. “I felt I had to escape myself and the responsibility of my own feelings of inadequacy. I didn’t love myself, not at all,” he told me.

As our tour down memory lane unfolded, and he was confronted with the physical remains of his past, it turned into a very emotional day. Almost everywhere we went, the landmarks we sought had either been removed, replaced or, in the case of the Marquee and several of the other pubs, reduced literally to piles of rubble. Everywhere we went he was confronted with personal goodwill from the people who recognised him, tinged with a sense of sadness at the inexorable, careless march of time.

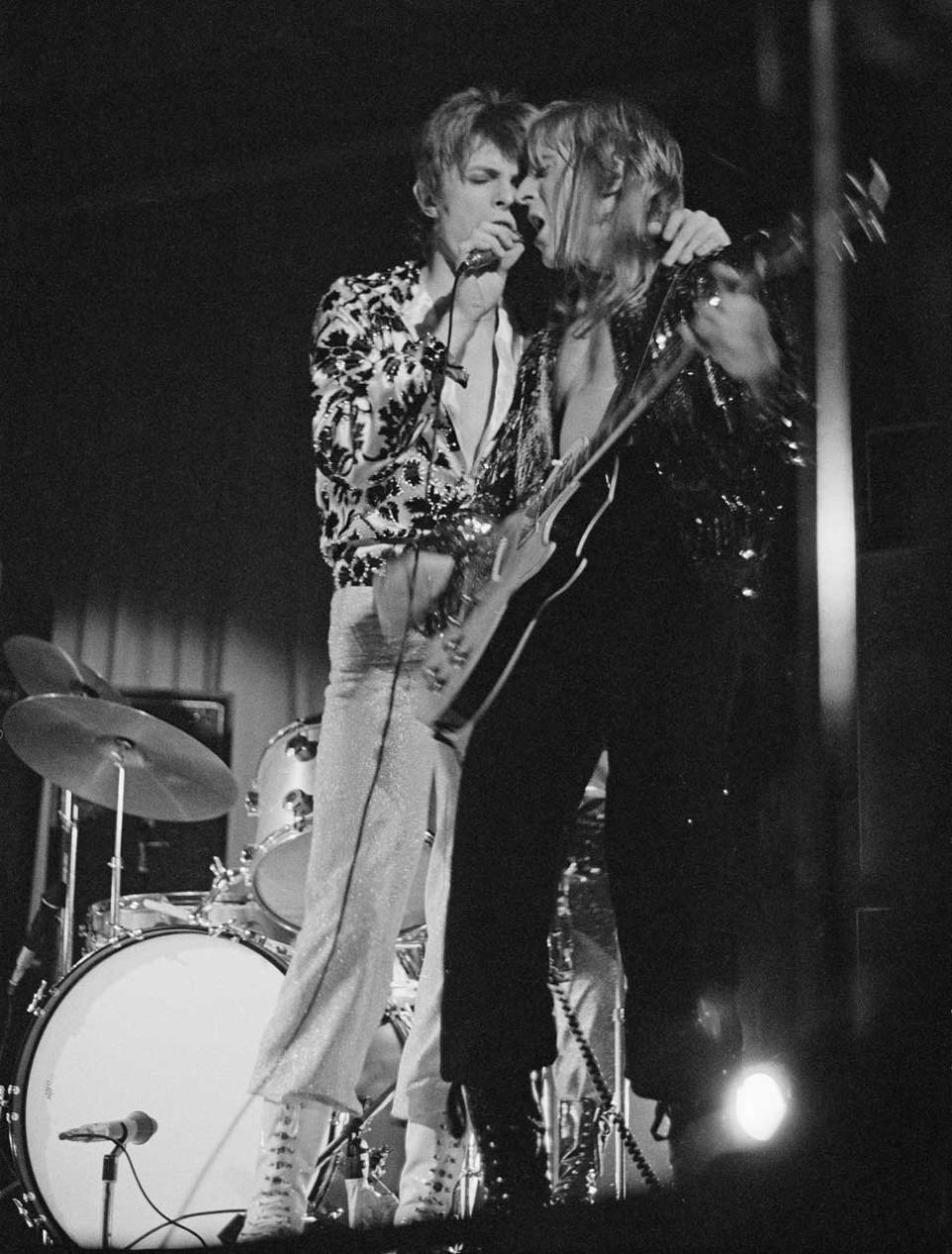

It was also a period of personal sadness. Guitarist Mick Ronson, the erstwhile chief Spider From Mars, was desperately ill, and would die within a couple of weeks of our meeting. Bowie and he had kept in contact. Indeed Ronson had played on one of the tracks on Bowie’s latest album, Black Tie White Noise. As we talked about his ailing comrade, Bowie struggled to keep from crying. “I’ve never bought in to any organised religion,” he said. “But now I have an unshakeable belief in God. I pray every morning.”

I saw many facets of Bowie during that day in London. I discovered that while he did everything else right-handed, he wrote with his left hand. I noticed his instinctive courtesy, and his impeccable, old-fashioned manners. How, when we both had to get in the car from the same side, he always stood back and waved me forward before jumping in himself. I also glimpsed something of Bowie’s uncanny ability to bring the best out of those around him. He was a creator, of course, one of the most talented and imaginative songwriters and performers that the pop world has ever known. But he was also a curator and mentor and nurturer of other people’s talent.

His antenna for locating raw talent was so finely tuned and his success at developing it was so consistent throughout his career that there is a tendency to take this side of his achievements for granted. Starting with Mick Ronson, he brought a succession of brilliant, imaginative guitarists from relative obscurity and launched them into the mainstream, most notably Earl Slick, Carlos Alomar, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Reeves Gabrels, Adrian Belew and bass guitarist Gail Ann Dorsey.

“He was very straightforward,” Mick Ronson said towards the end of his life, as he reflected on his time with Bowie. “He knew what he wanted to do and he got on and did it. He was a giving sort of person, a kind person. There weren’t any messing about. As soon as I met him I knew he was going to be a star. You get that vibe sometimes. And he had it. Later, after the Spiders were finished, he encouraged me to get into production and arranging.

"I remember a meeting we had with Dana Gillespie, and she wanted some string arrangements. And David said: ‘Oh, Mick can do that.’ I’d never done it before in my life. But he was very good at pushing you into doing things. David was always good at pushing you forward. It was one of the greatest things about him.”

Carlos Alomar, who along with Earl Slick was one of Bowie’s longest-serving guitarists, remembered his insatiable curiosity. “He wanted to know everything… He had this odd way of being rock’n’roll but still funky.”

“He completely, single-handedly altered the course of my life,” said Gail Ann Dorsey. “His image is that he would be a freaky guy that dressed funny. But he was a real gentleman. Nothing about him was flashy or ostentatious or over-the-top. He was very normal. It was just that everything around him was huge. But he was just a really gracious man.

"He was this incredible mentor. I feel so privileged to have had this opportunity to learn about music and being professional and stretching and doing things that I didn’t think I could do. Like Under Pressure. I said to him: ‘There’s no way I’m going to be able to sing and play that.’ He was like: ‘I’ll give you two weeks.’ And then he walked out of the room. So I had to figure it out.”

It wasn’t just guitarists. The late soul giant Luther Vandross got his first serious commercial break when he toured as Bowie’s backing vocalist in 1974, and shared a writing credit with Bowie for the song Fascination on Young Americans (1975). And there was Mike Garson, the pianist who is said to have played on more Bowie albums than any other musician. He first showed up on the track Aladdin Sane.

“It was just two chords,” Garson later explained. “And Bowie said: ‘Play a solo on this.’ I had just met him, so I played a blues solo. But then he said: ‘No, that’s not what I want.’ And then I played a Latin solo. Again Bowie said: ‘No, no, that’s not what I want. You told me you play that avant-garde music. Play that stuff.’ So I did the solo that everybody knows today, in one take. And I still receive emails about it, every day. I always tell people that Bowie is the best producer I ever met, because he lets me do my thing.”

When Bowie wasn’t discovering and nurturing new talent, he was rescuing the careers of those who had inspired him in the first place. He produced albums for Lou Reed (Transformer, 1972) and Iggy Pop (Lust For Life, 1977), and wrote hits for them and other acts, most famously Mott The Hoople, whose entire career turned around after Bowie gave them his (unrecorded) song All The Young Dudes to release as a single in 1972.

“He was a nice bloke, really generous with his time as far as my band was concerned, very helpful,” said Mott’s mainman Ian Hunter. “He was full-on. He was strange; one eye was a bit dodgy. You had a feeling he was slightly otherworldly but… he was perfectly normal. We didn’t know much about studios. David knew how to mic stuff and so did Mick Ronson. Working with him in the studio was a learning experience for us.”

In his long and constantly evolving career, Bowie ‘invented’ – or at the very least helped to popularise – the electronica music genre with his Berlin Trilogy of albums Low (1977), “Heroes” (1977) and Lodger (1979) recorded in collaboration with Brian Eno. Bowie’s UK No.1 single Ashes To Ashes was accompanied by a ground-breaking video incorporating cameo appearances by Steve Strange and others from the London Blitz scene who would go on to kick-start the UK New Romantic movement of the 1980s.

Bowie had a talent for collaboration that went way beyond the normal parameters. Everyone remembers the unintentionally hilarious version of Dancing In The Street which he recorded with Mick Jagger in 1985 on behalf of Live Aid, and the blockbuster hit Under Pressure which he wrote and recorded with Queen. But there were also more counter-intuitive collaborations, none more so than when, in 1977 at the height of the punk explosion, he recorded a TV special with the aging American crooner Bing Crosby. The unlikely pair sang a duet of The Little Drummer Boy, a Christmas song written by Katherine Kennicott Davis in 1941.

People thought Bowie had gone nuts. But there was a strange chemistry at work. Crosby was impressed with Bowie’s professionalism, and described him a few days after the recording as a “clean-cut kid and a real fine asset to the show. He sings well, has a great voice and reads lines well.”

The faintly surreal nature of the pairing was reinforced when Crosby died just five weeks later and the performance acquired a unique poignancy. When the song was eventually released in 1982, as Peace On Earth/Little Drummer Boy, it became a massive hit, prompting the Washington Post to declare that it was “one of the most successful duets in Christmas music history”.

However, if there was one project of Bowie’s which combined his collegiate instincts with his unerring genius for reading the lie of the musical land it was Tin Machine. In 1988, tired of being hemmed in by commercial and artistic expectations of him as a mainstream, stadium superstar, he realigned himself as the singer in a democratically organised, four-man heavy rock band featuring guitarist Reeves Gabrels together with the brothers Tony and Hunt Sales on bass and drums respectively.

I met Tin Machine in Dublin in 1991, when they were preparing for a European tour. It was a completely different experience from hanging with Bowie on his own. For one thing, he wouldn’t say or do anything without the explicit involvement and, it seemed, implicit approval of his bandmates. From shaking hands and saying hello to even the most important pronouncements about musical direction or lyrical content of Tin Machine, they imposed a strict philosophy of one for all and all for one – in an interview situation, at least. This was admirable in many ways, but also laborious and not an especially fruitful way of conducting enquiries.

The band chemistry and camaraderie seemed real enough. The Sales brothers had a typical brotherly (and rhythm-sectionly) knockabout sense of humour. Gabrels was altogether quieter and more cerebral. He and Bowie shared an art-school background.

“Bowie would say: ‘This song needs to have a gothic cathedral structure’,” Gabrels explained. “Or ‘This solo needs to be a bit Jackson Pollock.’ And then I could come back with something that was a take on the ‘splatter’ technique. When we weren’t in public he reminded me of the guys I hung out with, particularly one of my roommates. He was like an older brother to me. He taught me a lot about the industry and the way things work.”

And Bowie was Bowie. Talking to Tin Machine, all together, produced a situation that was reminiscent of those chaotic Beatles press conferences, where the interviewer would be faced with an overlapping barrage of in-jokes and deadpan one-liners. All very entertaining, but not revealing anything very much about anything. And, ultimately, swimming against the tide. For whatever they said or did, the reality of Bowie’s celebrity and charisma overshadowed any theoretical notion of an ‘equal’ group dynamic.

While the formation of Tin Machine represented a bold sidestep for Bowie, it was like waving a magic wand over the lives of the others. In the not too distant past, Gabrels had been sweeping floors in a music store and giving guitar lessons in the evening. The Sales brothers, whom Bowie met in 1977 when he and they played together in Iggy Pop’s backing band, had all but given up playing by the time they got the call to join Tin Machine.

While the obituaries and retrospectives all sidelined this period of Bowie’s career, there is no doubt that, musically, the Tin Machine albums are the moment when Bowie most closely and successfully aligned himself with the classic rock aesthetic. Bowie had an understanding of and affection for hard rock that was at least as great as his love of American R&B or electronica.

The Width Of A Circle (the track which opened The Man Who Sold The World) with its long, complex arrangement and Mick Ronson’s whiplash guitar solo, was an early foray into the genre. Songs such as Cracked Actor and The Jean Genie (from Aladdin Sane) had a similarly brash, rock approach, while Earl Slick’s wall of feedback at the beginning of the title track of Station To Station prefigured any number of similar efforts by bands from Screaming Trees to Sonic Youth.

Go back, right now, and check out the first self-titled Tin Machine album and you will find a collection of stark force and intelligent aggression. A huge, ambient drum sound and whip-smart, striding bass lines underpin the wailing, gnawing urgency of Gabrels’s heavily treated guitar tones. For Bowie it was clearly a tremendous release, and his vocal performances and lyrics are as strong and focused as any he ever produced.

‘I’m waiting on the fire escape/I’m not exactly well/I’m neither red nor black nor white/I’m grey and blown to hell,’ he sings on the album’s title track, a number with a typically urgent tempo and theme. Released in 1989, the year the Berlin Wall came down, the album reflects the sense of geo-political turmoil and tension that was in the air. Under The God was as explicitly political as Bowie ever got in his own writing (‘This is the West get used to it/They put a swastika over the door’), while a version of John Lennon’s Working Class Hero was spat out with true venom.

The first Tin Machine album reached No.3 in the UK chart and, by any sane calculation, was a huge success. Not only that, it also clearly heralded the grunge explosion that was about to take place. Indeed two weeks after the release of the second album, Tin Machine II, Nirvana’s epochal Nevermind album hit the shops.

Once again Bowie had been ahead of the curve, musically and sonically. Unfortunately on this occasion he was in the wrong place (not Seattle) and had chosen the wrong uniform (Tin Machine wore smart, middle-aged suits). Even Bowie was not a sufficient master of disguise to be able to cut it in plaid shirts and ripped jeans.

He had more zeitgeist-surfing tricks up his sleeve, of course. Having invented Brett Anderson, Bowie rather cheekily displaced Suede’s first album at No.1 in the UK with his own Black Tie White Noise album in 1993. His albums thereafter always reached the Top 10, whether he was turning out weird concept pieces with Brian Eno (Outside, 1995) or dabbling with drum and bass/jungle beats (Earthling, 1997).

The end came with Blackstar, released on January 8, 2016, Bowie’s 69th birthday. Produced by Tony Visconti and featuring a New York jazz band, the Donny McCaslin Quartet, as his backing group, the album was written and recorded during the 18 months that Bowie had been suffering – unbeknown to the world – from terminal cancer. As the Australian broadcaster Mark Pesce observed: “Bowie looked Death in the eye and thought: ‘I can use this.’”

Bowie died two days after Blackstar was released, a monumental tragedy – but also a feat of dark, theatrical timing as impressive as anything he had previously achieved.