'David Bowie: The Last Five Years' director talks icon's life and legacy

Jan. 10 marks the two-year anniversary of David Bowie’s passing, and Francis Whatley, for one, remembers exactly where he was the day the music icon died: in bed. “I slept in that morning,” the British documentary filmmaker recalls. “I don’t know why, because I never sleep in! But that morning something protected me, and I woke up to 27 messages telling me that Bowie had died. I think I was fairly numb; I couldn’t quite believe it.” Whatley’s grief wasn’t just due to his status as a lifelong Bowie fan. In 2013, he made the BBC documentary David Bowie: Five Years, and developed a cordial, if not necessarily close, relationship with the man behind the artist. “We were in email contact, but we didn’t talk about that film at all while I was making it. We talked about literature and art and that sort of thing,” he says.

In the wake of Bowie’s death, the BBC commissioned Whatley to make a follow-up film, thus allowing him to channel his sadness into something productive. The finished product, David Bowie: The Last Five Years, evaluates Bowie’s legacy through the prism of the prolific five years leading up to his death, when he recorded two new albums and oversaw a Broadway show even as he privately battled liver cancer. Premiering on HBO tonight at 8 p.m., the film should provide fans a way to process their lingering grief. It certainly fulfilled that function for Whatley: “I didn’t process [Bowie’s death] during the making of the film, but I did when I watched it back as a viewer rather than as the director.”

Yahoo TV: Having made a previous film about David Bowie, did you find it easier securing permission to make The Last Five Years?

Francis Whatley: Yes. I think if I had come in fresh, it would have been very difficult. I had a fair wind behind me from the first film, so his colleagues and the contributors knew the sort of filmmaker I was and that I was going to respect David’s privacy and concentrate on what was special, which was his music. That helped a lot, as did the fact that I was a fan, because I knew the subject.

Did Bowie watch the previous documentary? If so, did he speak with you about it?

He did. He asked me to send him a copy of the film before it aired [in England] on the BBC, and I had to say no. He understood how the BBC worked, and found it quite funny. I said, “What I will do is have the film delivered to your apartment in New York so you can watch it at exactly the same time!” He sent me an email immediately after it was finished saying — and this is verbatim — “Dear Francis: I’m very proud of you. David.” That was a big thing for someone who had been a fan since my teenage years. Both of my parents died a long time ago, so in a bizarre way he had seen more of my work than any other human being, and he critiqued it all. That he was proud of the film I made about him meant a lot to me.

Would you have preferred to make this documentary with his involvement?

It would be a lie if I said no, but I think you would have gotten a very different film. I’ve read so many interviews with him, and you realize that he does repeat himself quite a lot. Certainly by the end of “A Reality Tour” when he had his heart attack and disappeared from the public gaze, he had really said everything he wanted to say. So I’m not sure that if I’d worked directly with him on a film about him that it would have been more illuminating than the film we already had. To work with him on a film not about himself would have been amazing, and we did talk about that on various occasions.

What were some of the projects you discussed?

We’d been commissioned by the BBC to make a four-part, four-hour series on 20th-century British art. Sadly, there was a contractual problem that had everything to do with the BBC and nothing to do with David Bowie that put a spanner in the works. It was a great regret of my career that it never got made.

Because Bowie became such a private figure in the latter part of his life, what’s something you learned about him that would surprise others?

I suppose the integrity of the man. Right up to the end, he wasn’t going to use social media or the press to talk about his tragic battle with cancer. He was just going to do it in a very dignified way and carry on as if nothing had happened. He remained a very private and shy individual right up to the very end. He said to the world, “This is who I am through my music.”

Did he have any unexpected pop culture favorites?

He was a great SpongeBob fan, and played a king in an episode. He had this wonderful English accent in it. I guess his daughter was a fan, and that’s how he got into it. But who knows? He may have just gotten into it independently! [Laughs]

Throughout his life, he had a very carefully curated public image. Did you want to show viewers what lay behind the mystique of David Bowie?

I suppose there’s this tall poppy syndrome — a desire to pull down our heroes. I don’t have that desire. He was a human being with all the frailties we all have. He wasn’t a superman, but he was a genius. Concentrating on his professional career was the way to go; people’s private lives are their private lives, and what made him exceptional was the fact that he produced a body of work that will be listened to for hundreds of years.

But even in regard to the mystique of the artist — there’s a tendency to accept the idea that genius comes naturally to certain individuals. Were you interested in the work that went into his art?

I recently watched a movie about the photographer Mick Rock, and there’s a bit at the end where David Bowie is heard in voice-over talking about the divorce between the man and the artist. The artist is something independent, like in the Twilight Zone; it’s hard to talk to an artist about why they do something. It comes from their soul, and it’s hard to articulate that. He had a cut-up technique where he was throwing things from all aspects of his life — from his own personal history to the books he’d read and films he’d seen — into his lyrics. He may have been an amiable, genial, courteous, very amusing man, but I think he suffered the black dog like many of us do.

We hear different accounts in the documentary about Bowie’s attitude toward fame, with some claiming he welcomed it, while others mention his distaste for it. Do you have any thoughts on how he ultimately felt about his celebrity?

I think we all would like some of the trappings of fame. There are obvious advantages, financial being one of them, as well as a sense of validation. He wanted to be famous in the ’60s and early ’70s, no doubt about it, but there’s a reason why “Where Are We Now” is on [the 2013 album] The Next Day. One of the happiest periods of his life is when he was riding around on a bicycle in Berlin completely unnoticed when he had already made huge albums that made him a superstar. I was told stories that when he went to see his manager in London, he’d put a hat or hoodie on and take the bus. He was desperate to be like the rest of us.

At the same time, he must have been aware of the impact he had on people. How did he view his influence that way?

You’ll have to phone heaven to get the answer to that one! [Laughs]

Well, in your specific case then, did you tell him that you’d been a fan since childhood when you spoke with him the first time?

I was very careful not to say that. I thought I would embarrass myself and him more than I do normally. The fact that he put everyone at ease made it much easier. He called you by your first name and just appeared to be so normal that it was hard to see him as this superstar. He was a superstar, but he wasn’t. I don’t know if the superstar was David Bowie, or if the normal guy was the real David Bowie, or if it was someone else. He played many parts, and being Joe Normal may have been another role.

He certainly adopted a number of different identities in his music over the years. Was he able to keep a sense of self despite that?

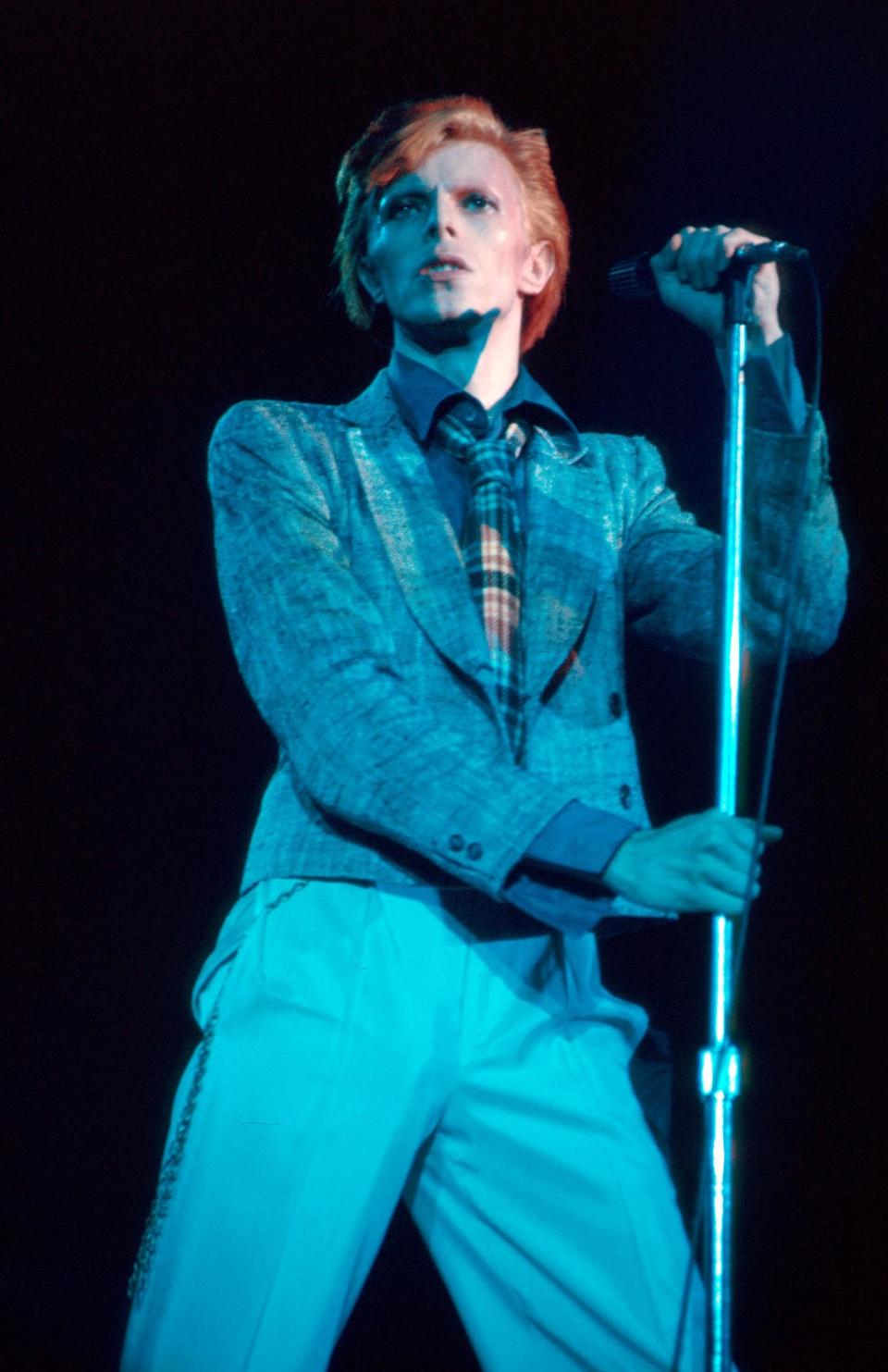

Of course. These were just parts and costumes. I don’t think he really believed he was Ziggy Stardust or the Thin White Duke. Although, the amounts of things going up his nose might have encouraged him to believe he was the Thin White Duke for a small amount of time! But he soon got out of that illusion. He sang a song on Ziggy Stardust called “Hang On to Yourself,” and that’s what he did: He hung on to himself.

Besides Bowie, 2016 also saw the deaths of music icons like Prince and George Michael. What does it mean for fans to lose these artists — to see that they’re not immortal?

It’s difficult, because Bowie was part of the first wave of rock, perhaps the golden age of rock. Lennon has passed away, but we’ve still got McCartney, we’ve still got Jagger, we’ve still got Neil Young. There are some giants to come over the next few years who will pass away. That he was the first of the golden generation to pass away in recent times meant a lot.

Is there another artist whose inevitable passing will cause that level of worldwide mourning?

Bob Dylan and Paul McCartney. But I think a lot of the public thought that David Bowie was talking directly to them. I don’t know whether people feel that about Bob Dylan. Maybe they do. About Paul McCartney? I’m not sure. There was a resonance people had with Bowie that was fairly unique, and that’s why his passing has meant so much to so many people.

Are there any current musicians you see having the same resonance as Bowie?

No. [Laughs] I’m trying to be generous here and not be an old man. But I seriously can’t. Of the current generation, there are people I genuinely respect, like Kendrick Lamar. But whether we’ll still be interested in Kendrick Lamar in 10 years, I don’t know. Maybe we will!

I’ve got to ask — what’s your favorite Bowie song?

That changes from day to day. I love “Drive-In Saturday,” I love “Heroes,” I love “Scream Like a Baby,” “Absolute Beginners,” “I Would Be Your Slave” — we could be here a while! [Laughs]

David Bowie: The Last Five Years premieres Jan. 8 at 8 p.m. on HBO.

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment: