Let's Dance: How Nile Rodgers transformed David Bowie from arty outsider to global superstar

A new David Bowie was born on a beach near Hastings in the summer of 1980. Bowie was on location filming the video for Ashes To Ashes, the song that would become his second No.1 single, when something happened that, he said, profoundly changed him.

Director David Mallet was filming Bowie as he walked up the beach dressed in the pierrot outfit he wore on the cover of Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), when an old man and his dog walked into shot. The director and crew yelled at the guy, asking him to get out of the way. The man – who probably walked there every day – was unfazed: “Screw you,” he said, “this is my beach”.

So Bowie took a seat next to Mallet and waited for it to blow over. Eventually the old guy is walking past and Mallet says to him, “Do you know who this is?”

The old guy looked Bowie up and down. “Of course I do,” he said. “It’s some cunt in a clown suit.” Bowie thought it was hilarious (“That was a huge moment for me,” he said later. “It put me back in my place and made me realise, yes, I’m just a cunt in a clown suit”) but it had a wider impact. When he told the story years later, Bowie said the incident “profoundly changed” him. The “whole facade”, he said, “came crumbling down”.

Things were changing in the world of David Bowie. His relationship with manager Tony DeFries and Mainman finally ended in 1982 after a protracted split. Scary Monsters had been his last album for RCA, the label that had been his home since Hunky Dory in 1971. The label was milking his back catalogue with compilations – Changes One, Changes Two, Rare. For Bowie, a new multimillion-dollar deal with EMI offered a fresh start.

In an interview with The Face magazine before the release of Let’s Dance, writer David Thomas suggested that EMI would be banking on Let’s Dance repeating the success of the Rolling Stones’ Some Girls album, a hugely successful record inspired by New York’s disco scene.

“Absolutely,” said Bowie. “The kind of enthusiasm they’ve shown is peculiar for me. I mean, I’ve never had that kind of thing shown to me for years!”

He talked about his older albums as sounding like historical artefacts. “I want something now that makes a statement in a more universal international field,” he said.

A year earlier he’d bumped into Nile Rodgers in New York. “To me,” Rodgers wrote in his autobiography Le Freak, “Bowie was on the same level as Miles and Coltrane, James Brown and Prince, Paul Simon and Jimi Hendrix, Joni Mitchell and Nina Simone. In other words, he was a genuine, creative artist, doing what I called ‘that real shit’.”

The two men bonded over a love of jazz. Rodgers had been brought up in a bohemian household where he’d come home to find “Thelonious Monk, Nina Simone, Miles Davis hanging at our apartment”. As a guitar player he had been infatuated by jazz legends like Wes Montgomery and Django Reinhardt, and later the guitarists of Motown, and funk players like Eddie Hazel, Jimmy Nolen, Willie ‘Beaver’ Hale. Like Bowie, he was a walking musical encyclopaedia and loved it all: rock, pop, soul, R&B, blues, jazz.

The meeting was a coincidence, but a lightbulb must have flickered in Bowie’s head. Nile’s band Chic – formed with bandmate and bass player Bernard Edwards – had become one of the most influential bands of the late 70s and early 80s. They had huge international hits – slick, funky, stylish tracks like Good Times, Everybody Dance, Le Freak – and, with their astonishing bass lines and mercurial guitar playing, had inspired everyone from Queen to the Sugarhill Gang, from The Clash to the Blockheads. Elegant and cool, with grooves that could raise the dead, Rodgers was fresh from producing and co-writing Diana Ross’s biggest album, 1980’s Diana. People were calling him The Hitmaker.

The pair set about making a record together, Rodgers excited at the prospect of pushing boundaries with a big star who was plainly unafraid of experimenting. They listened to records they might take inspiration from. Bowie told The Face that he listened to “much older stuff” before making Let’s Dance because he wanted to avoid modern trends. He said he wanted “things that I wasn’t going to pull apart… Things like the Alan Freed Rock’n’Roll Orchestra and Buddy Guy, Elmore James… Albert King, Stan Kenton.”

“We searched around listening to all these different records,” Rodgers told the Rolling Stone podcast, Music Now. “We were just looking at everything from Hapshash And The Coloured Coat, Mott The Hoople, Peanut Butter Conspiracy. Like ridiculous stuff, from the hippiest hippie stuff to The Ventures.”

Eventually, Rodgers played Bowie some material for a solo album he was working on. He explained how he had been trying to innovate and experiment, how he believed artists had to push boundaries, when Bowie stopped him. “I want you to do what you do best,” he said. “I want you to make hits.”

The first song they worked on was Let’s Dance. Bowie strummed it on an acoustic to Rodgers, who says it sounded like “Donovan meets Anthony Newley. And I don’t mean that as a compliment.”

“I felt that a lot of his songs were lacking in ear candy,” he told Rolling Stone.

The song was so basic that Rodgers wondered if it was a test. “I just thought that he was [testing] me to see if I was a sycophant.” He asked Bowie if he could try and arrange it differently. In video interviews since, Rodgers has demonstrated how he took the folk song, and made it first jazzy (“I knew that he liked jazz”) before making it brighter and choppier – into the weird mutant funk track we know today.

“I explained to him that every song I’ve ever written starts with the chorus,” says Rodgers. “He says: ‘Really? That’s crazy. You build to the chorus.’ I said: ‘Yeah – well, if you’re white you build to the chorus.’”

Nile’s theory was that radio stations gave black records less time to impress them, so you had to cut to the chase – don’t bore us, get to the chorus. He won the argument: on the track, after the Isley Brothers/Beatles Twist And Shout-inspired build-up, the chorus and the title are the first words out of Bowie’s mouth.

Bowie had another secret weapon up his sleeve. At the 1982 Montreux Jazz Festival he’d caught a performance by an up-and-coming blues guitarist called Stevie Ray Vaughan, whose Albert King-inspired playing was in sync with Bowie’s listening at the time. “He completely floored me,” Bowie said. “I probably hadn’t been so gungho about a guitar player since seeing Jeff Beck with his [pre-Yardbirds] band The Tridents.”

Was Stevie Ray a Bowie fan? “To tell you the truth, I wasn’t very familiar with David’s music when he asked me to play on the sessions,” he said later. “David and I talked for hours and hours about our music, about funky Texas blues and its roots. I was amazed at how interested he was.”

Nile Rodgers had been tasked with putting together the band for the album. Worried that his Chic bandmates – bassist Bernards Edwards and drummer Tony Thompson – were too deep into their drug use, he brought in Omar Hakim (at that point famous for Weather Report and Carly Simon) and bassist Carmine Rojas (then with Rod Stewart). Recording at New York’s The Power Station, they nailed the title track in two takes. In Rodgers’s eyes, he’d been trusted to put the band together.

“And then [Bowie] brings in this guy Stevie Ray Vaughan, who none of us had ever heard of.”

The two guitar players soon became friends – Vaughan broke the ice by having barbecue from Texas flown in for all the musicians; Rodgers would later produce SRV’s final album before his untimely death in 1990.

Vaughan laid down fiery guitar parts on Let’s Dance, reworkings of two older tracks: China Girl (co-written with Iggy Pop for Iggy’s 1977 album The Idiot) and Cat People (co-written with and produced by Giorgio Moroder in 1981). His playing is the highlight of cover version Criminal World. It was a perfect collision of sounds, Vaughan bringing passion and grit to a project that could sometimes have seemed slick and clinical.

The finished album divided Bowie fans. At just eight songs long, tracks like Ricochet, Shake It and Criminal World seemed a bit like filler. On Without You – backed by Bernard Edwards and Tony Thompson of Chic – they channel Avalon-era Roxy Music. The new version of Cat People was more muscular. The singles did all the heavy lifting.

As well as the title track, there was Rodgers’ reworking of China Girl, transformed from Iggy’s muddy-dirge into a widescreen romance. Modern Love was a rock’n’soul pastiche with an infectious call-and-response structure.

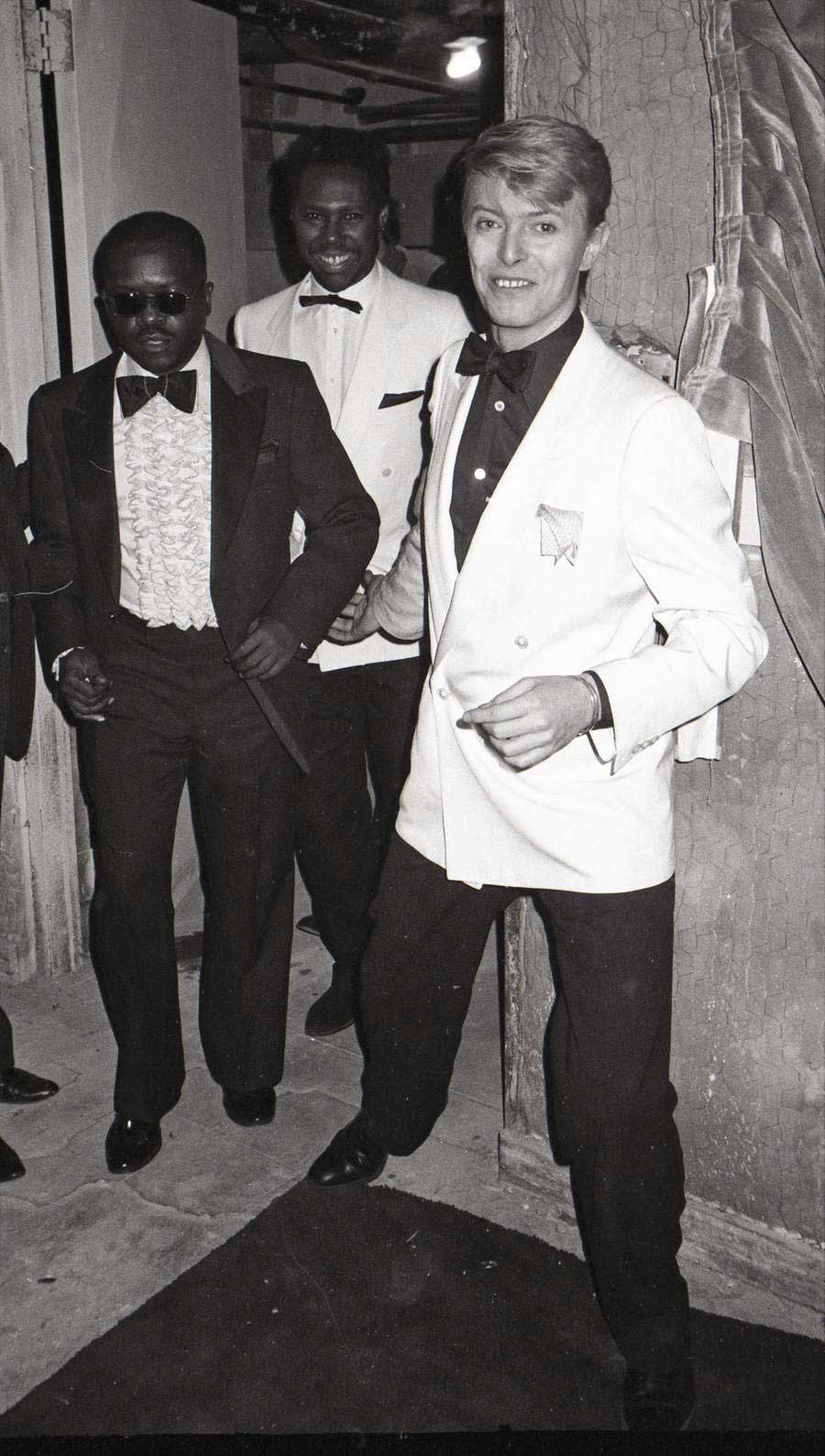

All three singles featured large on MTV. The TV channel was changing the landscape of pop, and the video for Let’s Dance unveiled the new Bowie. No longer “a cunt in a clown suit”, he was tanned, with a blond quiff and dangerous white teeth, singing an accessible, danceable pop classic. The David Bowie of Let’s Dance was a world away from the guy in the Ashes To Ashes video. Clean-cut, healthy, handsome, he was also unambiguously hetero: the video for China Girl featured him shagging on the beach, in a nod to the 1953 film From Here To Eternity.

To the disappointment of many, in an interview with Rolling Stone headlined “Straight Time: No more masks or poses” he disavowed his past. “The biggest mistake I ever made [was saying] that I was bisexual,” said Bowie. “Christ, I was so young then. I was experimenting.” It was pure revisionism for a more conservative age. “He is not gay, whatever he may have blurted out in 1972,” wrote interviewer Kurt Loder, “nor was he ever a transvestite, thank you.”

A generation of gay fans had felt liberated by Bowie’s claim to be bisexual a decade earlier. Now, it started to look like a PR stunt, or like he was moving back into the closet to appease middle America. In 2002 he admitted as much to Blender magazine: “America is a very puritanical place, and I think [being known as a bisexual] stood in the way of what I wanted to do,” he said. “I had no inclination to hold any banners or to be a representative of any type of people."

It was there on the record itself. Criminal World was a cover version of a song by British art-rockers Metro. Released as a single in 1977, it had been banned by the BBC for its ‘sexual content’: allusions to cross-dressing and gay sex. Bowie’s cover made plain his nervousness about his image.

The original’s lyrics ‘I’m not the Queen so there’s no need to bow/I think I see beneath your mink coat/I’ll take your dress and we can truck on out’ are changed to ‘I guess I recognise your destination, I think I see beneath your makeup/What you want is sort of separation’, and Metro’s later reference ‘I saw you kneeling at my brother’s door/That was no ordinary stick up’ was changed to ‘You caught me kneeling at your sister’s door.’ In the words of Bowie expert Chris O’Leary, he had “turned a gay-themed line into one that Vince Neil could’ve written”.

Metro songwriter Peter Godwin had been influenced by Bowie fan and was confused at the changes made to his lyrics. “It was a satire on androgyny, sexual ambivalence, posturing, pretending to be gay or whatever,” says Godwin. “It was just a light-hearted sort of fun exploration of what Bowie had launched when he came out as bisexual.

“'Kneeling at your brother's door’ – that could have just been voyeurism. It's all in the interpretation: you could be kneeling watching your older brother having sex. It could be anything and that's what I intended it to be. I wanted it to have more than one meaning.”

It looks like Bowie didn’t. “That's exactly what it is, isn't it?” says Godwin. “That's it.”

With all those sexual ambiguities out of the way, the door to the mainstream was kicked open. Let’s Dance became Bowie’s only single to go No.1 in the US and UK. The parent album went on to sell 11 million copies and turned Bowie into the international star he had wanted to be. By the end of 1983, it’s estimated that he earned around $50 million.

Nile Rodgers didn’t appear in the video for the title track or the follow-ups – China Girl, Modern Love – and Bowie didn’t invite him to go on the road for his Serious Moonlight Tour. In fact, as Rodgers pointed out: “If you notice all the interviews that he did, very few of them talked about me.”

Stevie Ray Vaughan had a similar experience. Originally, he explained later, he was just brought in for the album. “And then he asked me to do the tour, with [SRV’s band] Double Trouble opening up. It stopped because Double Trouble was really never ever included on the shows. He just wanted me to play with him.”

Bowie had form, of course. In 1970 he had been a struggling singer-songwriter with two novelty hits behind him – The Laughing Gnome and Space Oddity – watching with envy as his friend Marc Bolan reinvented himself as a glam-rock superstar. Mick Ronson and the Spiders From Mars reinvented Bowie musically and created some of rock’s best-loved albums, only to be fired after an argument over money. Bowie was an amazing talent spotter, but he could be cold and callous when it came to the people who helped make him.

“I don’t think that David had anything against me,” Rodgers told Music Now. “I think that he had what I would call survivor’s guilt. Like: you’re so successful you might be defined by this one record when your body of work is so vast.

“Looking at it from my perspective: that record [Let’s Dance], I made. Period. End of story. I mean, yes, David sang. Yes, he wrote songs, but basically, the way we made the album? Here’s what we did: we had a brand new studio and it had a really nice lounge. He went into the lounge, I made the record. He would walk in after we cut the track, and he would listen and give a nod of approval. I never once had him say: ‘Do that song again.’ He never said that. If you look at all the years that have gone by, you’ve never heard any outtakes from Let’s Dance.”

Bowie had worked the same way previously on Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane, giving sketches to the band on an acoustic guitar, leaving them to work them up into the rock songs we know and love. The Jean Genie, for example, “was knocked out in an hour on the second or third take,” according to bassist Trevor Bolder.

“He didn’t know one musician on that album,” said Rodgers, “other than me and Stevie Ray Vaughan. He had never heard Omar Hakim, didn’t know anybody.”

Maybe some of the critical responses to the album stung Bowie a little. From being the arty outsider, he was now a global superstar. Critics sniped that he had sold out, as though Nile Rodgers had forced him into making some terrible disco album. Back then, the mostly white music press was sceptical about pop music and dance music, which meant a genuine talent like Nile Rodgers could struggle to be taken seriously. Pop geniuses could look like Brian Wilson or Phil Spector, but not Nile Rodgers.

In fact, Let’s Dance helped break down divisions between black and white music. Famously, Bowie gave MTV a hard time for not showing enough black music on the channel. Let’s Dance was atthe vanguard of that, pioneering a post-punk dance music sound that defined the 80s. As Bowie commented: “At the time, [Let’s Dance] was not mainstream. It was virtually a new kind of hybrid, using blues-rock guitar against a dance format. There wasn’t anything else that really quite sounded like that at the time. So it only seems commercial in hindsight because it sold so many.

“It was great in its way, but it put me in a real corner in that it fucked with my integrity!” he said. “It was a good record, but it was only meant as a one-off project. I had every intention of continuing to do some unusual material after that. But the success of that record really forced me, in a way, to continue the beast. It was my own doing, of course, but I felt, after a few years, that I had gotten stuck.”

But it was his own doing. And it’s revisionism to suggest that Bowie hadn’t looked for hits in the past: Space Oddity was designed to cash-in on the Moon landing. From Starman to Fashion and Ashes To Ashes, Bowie wrote hits. He wasn’t some avantgarde artist with no interest in the mainstream.

“David said to me in no uncertain terms that he wanted me to make a hit album,” Rodgers said later. “Let’s be very clear: a hit album. Meaning he wanted every song to be popping like a Chic record or Sister Sledge.”

He got what he wanted and more.

For more stories like this, Bowie: The Complete Story is a special issue from Classic Rock, out now and available direct from Magazines Direct.