“David Gilmour doesn’t show anger often… that night, if he knew karate he’d have broken the table”: Fight over Comfortably Numb’s inclusion on The Wall was key moment in Pink Floyd’s history

The two shows Pink Floyd played at London’s Earls Court in May 1973 marked a quantum leap for the group out of the ballrooms and theatre circuit into the arenas, stadiums and fields, where their concerts would remain for the rest of their career. Thanks to the worldwide allure of their eighth album, The Dark Side Of The Moon, their controls seemed to be set; any intimacy and direct connection with the audience – never something highest on Floyd’s priority list – was over. Prog explores those shows and their impact on the group in the following years.

In 1980, Pink Floyd took to the stage at Earls Court, the cavernous 18,000-seater exhibition centre in west London. Booked for six nights in early August, the group performed a show that systematically parodied the very notion of an arena concert, introduced by an over-the-top MC, before sending four musicians onstage wearing Pink Floyd life masks; a surrogate band, proving that audiences at that distance could actually be watching anything. If that wasn’t enough to emphasise the dislocation, a physical wall was built between artist and audience made of 450 cardboard bricks.

The Wall became Floyd conceptualist Roger Waters’ most complex idea, a reaction to the general isolation in his role as conflicted multi-millionaire socialist, but specifically at the dislocation he felt as his group played live to ever bigger, increasingly soulless arenas. Always a band received with earnest silence from their fans, since the global success of 1973’s The Dark Side Of The Moon, rowdy elements of the crowd, especially in North America, asphyxiated the already slender rapport Waters felt with his audience.

But how did it come to this? How did a band, so experimental, stately and well-mannered get to this point? It all begins in exactly the same place, Earls Court, seven years earlier in May 1973.

There was much talk in early 1973 of Earls Court opening its doors to live concerts, yet there were few acts that could fill a hall of such size and scale. Built between 1935 and 1937, the storied venue was constructed on a triangle of land between train lines that had been used for entertainment grounds since the late 1880s. Its spectacular Art Deco/Moderne style was designed by American architect Charles Howard Crane, famous for his ‘movie palaces’ of North America, most specifically in Detroit.

The venue opened on September 1, 1937 – 40,000 square feet of space, complete with an indoor pool – with a chocolate and confectionery exhibition. From then on, it became the go-to venue for large-scale events such as the Royal Tournament, the Ideal Home Show, the 1948 Olympics and the Boat Show, where the indoor pool would be filled with almost eight million litres of water. But not live performances by rock bands. Yet.

For large concerts, London was served by Olympia, just up the road from Earls Court, with its 10,000 capacity. Jimi Hendrix and Floyd themselves had played there as part of Christmas On Earth Continued and, later, in one of his few ill-fated solo gigs, so did Syd Barrett. There was also the Empire Pool Wembley – again a 10,000-seater – which had opened its doors to concerts since 1960 with the NME Poll Winner shows.

After The Beatles had played to 57,000 at Shea Stadium in 1965, plus Woodstock in 1969 and the Isle Of Wight Festivals of ’69 and ’70, rock promotion became big business. And ‘big’ was the operative word – the bigger the better. The idea of festivals was now established, so if they could draw tens of thousands, surely the right band could fill a mere 18,000 seats in an arena. To facilitate this, a new breed of UK concert promoter was coming through, such as John and Tony Smith, Harvey Goldsmith, Maurice Jones and Mel Bush.

The idea to put on live shows at Earls Court came from showbiz impresario Robert Paterson and boxing promoter Jarvis Astaire (the man later responsible for bringing WWF to these shores). “Patterson came from the classical scene, very old-school,” former London agent and Thin Lizzy co-manager Chris O’Donnell recalls. “I used to see Jarvis around town a lot. I don’t think there was a pie that he didn’t have a finger in. He once claimed he was offered the management of the Fabs but turned them down because his wife didn’t like them. Pure fantasy!” But, of course, an element of fantasy is what is needed to pull off feats on such a large scale.

Firstly, Mel Bush was contacted about which acts of his he thought he could promote there. He had not one, but two of such magnitude: David Bowie and Slade. At opposite ends of the glam phenomenon, both had ardent fanbases that could guarantee sales. If the teenyboppers could potentially fill it, so could Pink Floyd’s fans, especially as The Dark Side Of The Moon looked as if it would be their biggest release yet. Negotiated by the team at housing and homeless charity Shelter, Floyd agreed to play a benefit concert. As ticket sales (priced at £2, £1.75 and £1) far exceeded capacity, a second date was added.

And so, on May 18 and 19, 1973, the group played two nights there, among only three shows they played in the UK in that particular year. They already had a taste of larger shows as they had played Wembley’s Empire Pool the previous October, and understood that the sound was so important to these halls. Their US tour in March saw them playing venues between six- and 12,000-seaters.

Although Slade had been booked first, at the end of their UK tour on July 1, David Bowie was announced first and opened Earls Court to rock audiences on May 12. Whereas his Hammersmith Odeon concert in July that year is revered by the world and its gnome, Bowie’s Earls Court show is frequently swept under the carpet. By all accounts, it was a shambles. The stage was too low, the PA inadequate and the show had to be stopped for 15 minutes to quell the excitable stage-charging crowd.

“There was a good deal of apprehension about the group playing at this enormous exhibition hall,” Pink Floyd biographer Rick Sanders wrote in 1976. “Some weeks previously, David Bowie had done a concert there, the first time the venue served as a rock palace, and both fans and critics had been unanimous in their verdict. The show was a disaster, with terrible sound and nobody able to see what was happening on the distant stage. Earls Court was definitely not for rock, everyone thought.”

Pink Floyd would be leaving nothing to chance. Their live shows had been building in scale for a couple of years, especially with the addition of lighting and effects technician Arthur Max, who would introduce cherry pickers cascading rose petals, or burning gongs to enhance the band’s desire to focus on ‘son et lumière’ rather than the group themselves (as Floyd academic David Pattie notes, “The band, with the occasional exception of Roger Waters, were static to the point of self-effacement”).

Even though it had been played live for over a year, the press were calling the Earls Court show the “première” of The Dark Side Of The Moon, which had been released that March. It was certainly the first time that UK audiences had seen the group augmented with Dick Parry on saxophone and female backing vocalists – on this occasion, Vicki Brown and Liza Strike. Thunderbirds (and later James Bond) special effects technician Derek Meddings coordinated a crashing Spitfire to shoot over the audience’s head, and Max worked on the lighting effects, as well as introducing the inflatables that would become so central to Floyd’s performances. A huge mirror ball rose behind Nick Mason’s drums and opened out – not unlike the jewel-encrusted satellites shown in Diamonds Are Forever, the then-recent Bond film – and sent laser light beaming across the auditorium.

Most importantly, given the criticism of Bowie’s shows, the sound team led by Chris Adamson employed the latest quadraphonic technology to exploit the auditorium’s vastness. “What I always found amazing was the sound in the room, how that took the music around,” Gilmour’s first wife, Ginger, who was there that night, recalls. “You didn’t just have it coming at you. You were enveloped into it. Rick’s keyboards were amazing. It was really special.”

Bootleg recordings of the concerts demonstrate how accomplished the group had become. From the hits’n’bits of the first half, opening with Obscured By Clouds and When You’re In, they sound enlivened by their US tour and happy to be scaling up that size of venue, filling the empty space with layers of well-mixed sound. Waters introduces Careful With That Axe, Eugene as another “extremely oldie.” A leisurely Echoes closes the first set. Then The Dark Side Of The Moon is presented straight, with little improvisation. A storming encore of One Of These Days sends the crowd home in rapture.

The second night’s performance is a lot roomier, with jams stretching out. If it had been able to stay this way during subsequent tours, maybe The Wall would never have happened. “It wasn’t, ‘Here’s a bit of a Spitfire,’” Ginger Gilmour continues. “It was bringing the multi-dimensional aspect of the music and the visuals more into one. It was theatre. It wasn’t a gimmick. It intensified the reality of the music, the experience and the oneness. It made the audience feel like a kid: ‘Wow!’ I remember the unity and the beauty of it, a beautiful concept. I loved it.”

The band were broadly happy with the way the show had gone. “All the elements came together, as we presented the piece in its most developed version,” Nick Mason wrote in Inside Out. “The music had been rehearsed enough to be tight, but was new enough to be fresh. The lighting, thanks to Arthur, was dramatic. There were additional effects including a 15-foot spotlit plane shot down a wire over the heads of the audience to crash onstage in a ball of fire in sync with the explosion in On The Run.”

Rick Sanders continued: “Their material might have been familiar but they put on the show of their lives for 18,000-strong audiences whose appreciation bordered on religious fervour. Floyd’s amplification amply filled the cavernous hall with quadraphonic magic, aided by visual effects of dramatic power. Roger Waters’ gong exploded in flame during Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun, an inflatable man loomed behind Nick Mason during Careful With That Axe, Eugene, his luminous green eyes glowing through dry ice clouds.” It was, as Melody Maker said, “A perfect moonshot, faultless in every department.”

Waters spoke to ZigZag magazine the week after the gig and still seemed in awe at the scale of what his band could achieve: “When we were setting up, I thought that it did look a bit like a circus with all these wires going into the audience. And the plane we used at Earls Court was very like those circus space rockets that people whip round and round in. It was silver and red and about six feet long, like a bloody great aluminium paper dart, flashing lights and smoke. Amazing.”

A bar had been set. The shows changed the band – thoughts of how subsequent records would scale up for performance became as much a consideration as what the sleeve would look like, what the music would sound like and what the concept would be. Never the most prolific of touring bands compared to their peers, their new-found success enabled further scarcity. Before now, Pink Floyd’s appearances had incorporated the experimental, moving forward with light and sound, cooking breakfast and sawing wood, yet these all seemed am-dram, even the original liquid lights, compared with what they had arrived at.

The very fact that Pink Floyd weren’t going to be coming to your town meant getting your money’s worth when you did see them. While each performance was to become a treasured memento for European fans, their reception in North America after they had hit the bigger stages was to lead to something altogether darker. In May 1973, 10 days before the Earls Court shows, Capitol US did what the group wouldn’t allow in the UK – release an edited version of Money as a single. The sarcastic blues-boogie taken out of context made Pink Floyd sound like everything they were not: a good-time bar band. Although its success didn’t greatly affect their remaining North American and European dates of the year, as time passed, it became an issue.

“Roger started getting really upset later, after Money became a success. We became more famous and the gigs got larger; intimacy was lost,” Ginger Gilmour says. “In earlier gigs, people listened. They allowed themselves to be taken by the music and they didn’t have to be on drugs to do it.”

Aside from commitments to a short French tour in June 1974, Pink Floyd reappeared onstage at Usher Hall in Edinburgh on November 4 that year, playing a 20-date UK winter tour that mixed multiple nights in smaller capacity venues with four consecutive nights at Wembley Arena. There was tremendous excitement for the group’s first UK tour in over two years. Demand was high. For example, the Cardiff concert at the town’s Sophia Gardens Pavilion received 9,000 applications for 2,000 tickets.

The weight of expectation of the live return weighed heavily on Pink Floyd. When this tour was announced, it was back to ’72 in terms of premièring new material in the first half of the show, before returning to familiar territory. And frankly, hearing Shine On You Crazy Diamond, and early versions of Dogs (Gotta Be Crazy) and Sheep (Raving And Drooling) cold was quite a big ask. And by now, although The Dark Side Of The Moon was becoming a tad hackneyed for Floyd, people had paid their money to hear their softly spoken magic spells.

For these 1974 shows, one of Pink Floyd’s most recognisable stylistic devices was added: the circular screen on which films could be projected – known colloquially within the group as ‘Mr Screen.’ Films were made for each number including director Ian Emes’ animated clocks for Time, and shots of Dark Side... being pressed up for Money. Pictures taken of the band by Jill Furmanovsky backstage show them positively at ease with each other.

“They were an organism,” Ginger Gilmour says. “Each one had a character, a quality that made it work: Roger was the outspoken visible person, Nick was the glue, David was more of the heart and the floating, Rick was even more introverted, but brought in a certain quality.”

The volume of the cheers at the first thud of The Dark Side Of The Moon’s heartbeat after the interval drowned out anything that was played in the first half, yet UK fans were respectful and knew how to behave. Tour manager Mick Kluczynski, who was also part of the group’s sound team, the ‘Quad Squad,’ said in 1976: “Pink Floyd fans come to a concert, sit down, shut up and listen, and go home quietly. The group have a very good reputation among hall managers.”

This was becoming less of the case in North America, where on the short two-part tour they undertook in April and June, at the gig at Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh, fights broke out in the 50,000-strong crowd. They detracted, as The Pittsburgh Press was to write afterwards, “from the mood so vital to appreciating Pink Floyd’s music.” Not even the brand-new Mark Fisher and Jonathan Park-designed inflatable pyramid could calm the nerves.

A despairing Waters was later to say: “I cast myself back into how fucking dreadful I felt on the last American tour, with all those thousands and thousands and thousands of drunken kids smashing each other to pieces. I felt dreadful because it had nothing to do with us. I didn’t think there was any contact between us and them.”

The tour ended with an enormous outdoor show at Knebworth Park on July 5, 1975, the only major outdoor concert they had performed in the UK since the Hyde Park show in July 1970. “Knebworth looked, initially, like a repeat of one of those glorious festivals that marked the zenith of progressive rock development in the late 60s,” Robin Denselow wrote in The Guardian. “The vast audience was sprawled across the English countryside, banners waving like a medieval battlefield, while the homely droning of Mr John Peel announced an impressive cast of musicians who used to be leaders of the so-called underground, and still retain their cult appeal. The underground has long disappeared, rock has become big business and respectable, and audiences are now more passive, demanding slickness and professionalism rather than experiment.”

When they did take the stage at Knebworth, the first hour was material completely unfamiliar to most of the audience – unless they had been to previous shows on the tour or bought a bootleg. To think a group would conclude their tour ahead of an album that had yet to be released today seems unthinkable. To go that long before ‘the hits’ would test the patience, and as seemed commonplace at this point, the show received mixed reviews. However, there was much to look at.

Sadly, technical delays hampered matters, as the band had to take to the stage as two Spitfires, flown in from East Midlands airport, buzzed the crowd. The electricity supply to the stage was variable, the band were tired, and the sound beset with issues. Rick Wright’s keyboards were out of tune, and, losing foldback to the stage, Waters sang out of tune. However, with pyramids and lights and explosions there was still enough warm thrill of confusion for the 100,000-strong crowd to enjoy.

The band spent the first half of 1977 on the final ‘proper’ tour they undertook with Roger Waters. This would be the one where their superstardom really hit home, with sales of Wish You Were Here – which arrived three months after Knebworth – proving a worthy successor to The Dark Side Of The Moon. Yet the band were determined to keep their anonymity – there would be no showboating or foot-on-the-monitor shenanigans.

As David Pattie notes, Pink Floyd “did not take advantage of the technologies they helped pioneer to declare themselves, unambiguously, to be stars. Instead, they allowed themselves to disappear behind the images they created; in fact... the stage technologies they employed came to stand in for the band in performance.” They were, in the stadiums at least, a surrogate band – people came to look at the lights.

To coincide with the release of Animals in January 1977, the group undertook a European tour, arriving in Britain in March for five nights at Wembley’s Empire Pool and four at Stafford’s Bingley Hall. Although keeping Dick Parry on sax, there would be no backing vocalists, thus removing any sweetening of the sound – instead, second guitarist Snowy White helped Gilmour recreate his multi-tracking from the Animals album. By now the spectacle was complete – beyond the usual explosions and projections one expected from the Floyd as a matter of course, there was now one of the most-loved aspects in Floydology: the inflatable pig. As seen on the cover of Animals, it would majestically hover above the audience’s heads.

Dave Bandana, writer and performer with prog outfit The Bardic Depths, was in the audience at the Empire Pool shows in March 1977. “Having seen Genesis perform The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway two years earlier at the same venue, I was expecting something similar, but without the costumes.” For Bandana, it was not to be. “My abiding memory is one of disappointment and I would tell people it was the most boring concert I ever attended. Maybe I expected too much.

“The music, of course, was wonderful but there was no interaction with the audience. It all felt very sterile, played exactly like the records. There was, of course, one theatrical moment: the pig on a wire. But I remember little else. Today I might appreciate it more, especially as I never saw them live again. But at least I saw them and witnessed a bit of musical history.”

As the European Animals tour became In The Flesh in the US from May to July 1977, all the dark forebodings of previous excursions coalesced. A pall seemed to hang over the band, and all the shows seemed to be downbeat. The staging had complex hydraulic lights rather than their usual ‘square rig’ illumination; these had umbrellas attached that could also protect the band from the elements. In addition to Mr Screen, the mirror ball, the pyramid and the pig, Fisher-Park designed a huge inflatable nuclear family to hover out over the audience in Dogs.

“The Floyd were mere puppets, it seemed, on the stage and in the distance,” Ginger Gilmour wrote in Behind The Wall. “I admired this, for it gave an opportunity to listen instead of adulating upon our stars. Taken on a journey, because that was the Floyd they loved. Admittedly, I wished that there was less tragedy, less angst. It was as if Beauty had become a whisper. The music was just about audible amongst the props and the click track. It was not to David’s liking, nor Rick’s, as the click track took over.”

Ginger added, “Sometimes I’d come out telling them it had been a really great gig and they’d go, ‘It was terrible.’ They’d have their headphones on, the click track and all that stuff. Sometimes they were almost doing covers to them. But it still transcended, at least for me.”

The final show of the In The Flesh tour was at the recently built Olympic Stadium in Montreal on July 6, 1977. Anyone with even a passing knowledge of Floyd lore knows where it all reached breaking point, with Waters reacting to the rowdy crowd with phlegm. It’s fascinating to think that in 1977, with all the ‘I hate Pink Floyd’ sentiment from punk, Floyd themselves would be the ones to gob on their audience rather than be spat at. David Gilmour had had enough as well, retreating to the mixing desk for the final encore.

“I’ll never forget the moment when David appeared at the mixer,” Ginger Gilmour says. “Poor Snowy White. He didn’t know that traditionally, at the last gig of every tour, they always did this breakdown. Little by little, all the equipment leaves and there’s poor Snowy, suddenly David’s gone and everything’s been taken away.”

The irony of the final thing that this line-up of Pink Floyd would play in a stadium was a listless blues jam, not unlike something that they would have played at UFO when starting out just over a decade previously. But, here in the brutalist Olympic Stadium, both UFO’s liquid lights and the band’s spirit had gone.

The effects of the In The Flesh leg of the Animals tour were deep and long lasting. “The last show we did under those really bad circumstances was in Montreal at Olympic Stadium to 90,000 people and my sense of it was that it was a bad joke,” Waters later recalled of that night. “It really had nothing to do with a group of people playing music and another group of people listening to them. It was a weird kind of religious rite and it made me very uneasy – I didn’t want to be involved in it.”

Ginger Gilmour, from her vantage point at the mixing desk, could see it slightly differently: “The energy was terrible. But at the same time, the unity of people – apart from the ones in the front row that were drunk, out of it on marijuana and making a lot of hoo-ha – they wanted intimacy. They wanted people to listen, because if you don’t listen, you don’t hear it. You need to become one. The majority of fans were sitting, listening, wanting to get lost in music and not partying.”

Relationships within the band had been slowly, almost impenetrably deteriorating since The Dark Side Of The Moon. Never a band of brothers as such, as success meant they had to spend less time together, it was almost as if strangers were reconvening every time they gigged or recorded. “There was terrible conflict,” Ginger Gilmour recalls. “Roger and Carolyne, his new wife, would always be in a separate limo, separate hotel... always separate. She was building up his belief so that he could break out of the chains that he felt we had.

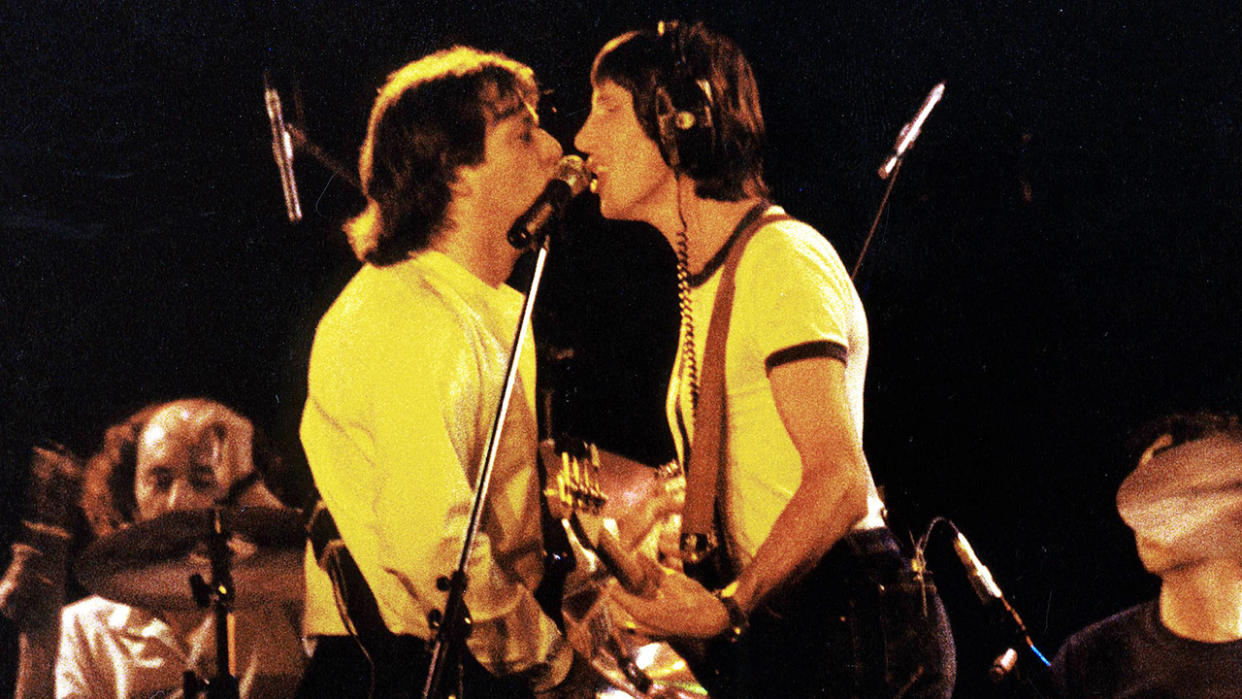

“We were in LA and they were working on finishing the album. They were talking about royalties, and we all met up at a Japanese restaurant. The day apparently had been really tough because Roger didn’t want Comfortably Numb on the album. David doesn’t show anger very often, but on that night, in the Japanese restaurant, if he knew karate, he would have broken the table with how hard he hit it. He said, ‘That fucking has to be on the album.’

“Well, for me, having gone through that summer where there was so much angst in the demos, and watching it evolve into something that we could watch, it represents the archetypal journey of us with chaos. When Comfortably Numb comes, it’s the release, it’s a hope. He’s up there, the light totally shifts and you’re absolved of all the angst. If that wasn’t there, it would be a terrible album.”

The Olympic Stadium would be Pink Floyd’s final show playing old material. When they returned to the live arena in February 1980 it would offer something completely different: a show based entirely around their new album, which contained two versions of a track called In The Flesh – one with a question mark and one without. Its opening line was: ‘So you thought you might like to go to the show...’

Designed specifically in three parts – an album, a live show and a film – The Wall channelled everything, good and bad, of what had been learned in the seven-year trajectory since Pink Floyd took to the stage at Earls Court in May 1973. It took all of Waters’ angst, and all the cutting-edge skills of the light, sound and construction team to create a show so grandly preposterous that it could only be staged in its original incarnation 31 times.

The band played it at Earls Court twice: for the six-night stint in 1980, and then a further five nights, for potential use in Alan Parker’s forthcoming film of the album, in June 1981. The show on June 17 that year would be the last time the four core Pink Floyd members would play together until their brief reunion in 2005.

Tales of The Wall, and what the size and scale of the concerts meant for the entire live concert industry, are legion. Sounds reported that “they dwarfed the biggest indoor rock venue in the country with a dazzling array of effects and a 360-degree sound system that was the finest I have ever heard anywhere, let alone the cavernous wastes of Earls Court.”

Earls Court always had a special place in Pink Floyd’s mythology. Nick Mason wrote in Inside Out that it was “one of our favourite venues, a place with plenty of character, right in the heart of London.” It was where the Roger Waters-less Floyd ended their live career with their run of shows in October 1994 to complete The Division Bell tour, and Waters played there again in 2007.

Tragically, the exhibition centre was demolished in 2017 and is now an empty space awaiting long-promised development. It was a venue that was far from perfect, but the group had an affinity with it – being less soulless than Wembley. The shows Pink Floyd played there between 1973 and 1981 bookended the most fascinating, not necessarily for all the right reasons, period in Pink Floyd’s career.