Did a tarot card reading predict the Rolling Stones’ Altamont disaster 50 years ago?

Fifty years ago, on Dec. 6, 1969 — "rock ‘n’ roll's all-time worst day… a day when everything went perfectly wrong,” according to Rolling Stone magazine — one of the greatest tragedies in music history occurred, at the Rolling Stones’ free festival at Northern California’s Altamont Speedway. The event had been billed as the “West Coast Woodstock” — just four months after the original Woodstock fest had taken place in Bethel, New York — but as it turned out, it was hardly a peaceful celebration a la the Summer of Love. In fact, Altamont came to symbolize, as the Village Voice once put it, the “death of the Sixties dream.”

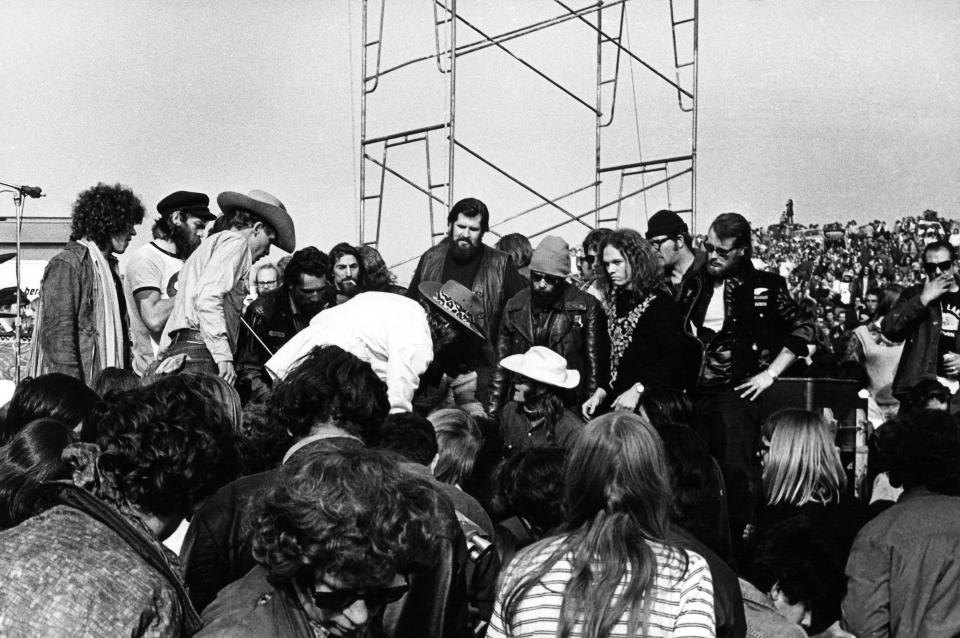

Altamont resulted in the actual deaths of four young attendees, among them 18-year-old Meredith Hunter. During the day, the festival — which along with headliners the Stones included performances by Santana, Jefferson Airplane, the Flying Burrito Brothers, and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young — devolved into violent chaos after members of the Hells Angels, who’d been hired as security guards, clashed with the rowdy, 300,000-strong crowd. Hunter was eventually fatally stabbed during the Stones’ performance of “Under My Thumb” by a Hells Angel named Alan Passaro (who was charged with murder, and later acquitted on the ground of self-defense); the horrific incident was captured on camera by renowned filmmakers Albert and David Maysles and used in the Stones’ tour documentary Gimme Shelter.

There were early signs that the poorly planned event, which was announced with just 10 days’ notice, would lead to disaster. A venue for the concert wasn’t even secured until Dec. 4 (after the Stones were denied a permit by San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, and then a deal to hold it at the Sears Point Raceway fell through at the last minute). And Mercy Fontenot, a member of the Frank Zappa-masterminded girl group the GTOs, recalls getting a bad feeling when she hung out with the Rolling Stones three days before the catastrophe, when she read the band members’ fortunes.

That evening, Fontenot and her bandmate Pamela Des Barres, a.k.a. the famous groupie and future author of the memoir I’m With the Band, were hanging with the Stones at the home of Monkees member Peter Tork, after they’d all attended a solo concert by their mutual friend Gram Parsons of the Flying Burrito Brothers. Even then, Fontenot knew something wasn’t quite right.

“The whole night had this feel of edginess, of agitation, even though we were having fun,” Fontenot recalls. “I had my tarot cards with me, and for some dumb reason decided I was going to do a reading for the Stones. First I read Mick [Jagger]’s cards, and I was scanning them nervously, thinking to myself, ‘OK, this is not good.’ The whole read-out was an utter tragedy. There was the Devil card, of course, which represents greed and obsession with power, and the final card was the Tower, which is a symbol for ambition constructed on faulty premises. I read Keith [Richards] and Gram's cards next, and it was same alarming result. Just no, no, no — ‘no’ was the one word going through my mind. All of the tarot cards looked horrible.”

Fontenot considered telling the Stones what she saw in the cards and expressing fears about the festival, but she knew there was no point. “The Stones kept babbling about Altamont and how great it was going to be, how it was going to be the most fantastic festival of all time. And there I was with my cards, thinking, ‘Oh my God, this is going to be just f***ing hideous.’ But I decided not to tell them what I saw, since I wasn’t going to be able to change their minds about going through with it anyway. Mick in particular was not going to listen to anything I had to say, because he clearly felt so above the law. Plus, Mick was a paranoid type as it was… and I didn’t feel like upsetting him. So I just lied my ass off and told them everything would be awesome. But I knew there was trouble ahead.”

Des Barres later wrote in her column for Please Kill Me that Richards had actually seen the Tower card and he knew that it symbolized destruction — but when he pointed this out to Jagger, the Stones singer replied with a shrug, “It’s too late to cancel.” So, three days later, against their better judgment, Fontenot and Des Barres attended the festival, where she Fontenot noticed yet another bad omen.

“The first thing that I saw was Mick with a bloody mouth. He’d been slugged in the head by some fan the moment he stepped out of his helicopter,” she recalls of Jagger’s assault by an intoxicated concertgoer — who’d raced up to Jagger screaming “I hate you!” upon the singer’s 3 p.m. arrival to Altamont Speedway. “I said, ‘Oh hey, Mick,’ and he had blood dripping from his lip. That certainly set the tone for the day. It all felt very dark and very gloomy, like a cloud was coming over everything, and I knew those tarot cards had been right.”

The crowd was restless and the air was charged with bad energy. The Grateful Dead, who’d been slated to perform, actually pulled out and vacated the premises after Jefferson Airplane singer Marty Balin was knocked unconscious by one of the Hells Angels in an altercation that transpired during his band’s performance. Fontenot also wisely decided to get off the grounds before the scene got too ugly.

“When the trouble started, there was lots of tugging and pulling. It looked like a mosh pit. Mick kept pleading with the crowd, ‘You’ve got to stop fighting. This is not right.’ I was already looking for an exit, so I wouldn’t get killed,” Fontenot says. “Mick tried to prevent me from leaving, but I didn’t feel any guilt about getting the hell out of there before disaster struck. I was despondent later when I heard about the stabbing, but mainly I was relieved that I didn't witness all that.”

Later, back at San Francisco’s Fairmont Hotel, where the Stones and their entourage were staying, Fontenot says she witnessed Jagger “losing his mind over what had happened at Altamont — pacing, freaking out, claiming he was never going to perform again.”

During the Stones’ Altamont set, the band had stopped their third song, “Sympathy for the Devil,” when a fight broke out in front of the stage. Clearly believing in the supernatural, Fontenot says the Altamont tragedy reminded her of another time when she’d had a premonition – “or some sort of sixth sense” — while attending a Rolling Stones’ playback session of that song at Hollywood’s Sunset Sound studio the year before.

“When I heard Mick intoning, ‘Who killed the Kennedys?/After all, it was you and me,’ I thought, 'What is he doing? He is tempting fate. He's really messing with some Kenneth Anger-type s***here,’” she says. “It was satanic mastery. I don’t believe Mick was seriously into the occult or devil worship, but I think he was toying with it because he thought it sounded mysterious and cool. Maybe he was just playing, but he was playing with fire, and it was all too heavy for me. So, when Altamont went down, I think it was all tied in.”

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment:

When Sha Na Na opened for Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock: 'Hippies thought they were on a bummer!'

Bill Wyman remembers 'absolutely brilliant’ Rolling Stones bandmate Brian Jones, 50 years later

When riots erupted at Woodstock '99: 'We looked like we were the bad guys'

Jagger, Richards talk 'Some Girls' 40th anniversary: 'Punk rock was a kick up our ass'

Want daily pop culture news delivered to your inbox? Sign up here for Yahoo Entertainment & Lifestyle’s newsletter.