What Disney’s Beach Boys film doesn’t tell you about Brian Wilson’s broken brain

In November 1969, the American network television channel CBS set up their cameras and microphones for the filming of a Beach Boys special introduced by none other than Leonard Bernstein. The timing was less than optimal: the group as a whole were in disparate straits, while their principal songwriter, Brian Wilson, was in the foothills of the kind of mental disrepair that would imperil his wellbeing for decades to come. Even so, when Wilson played an unaccompanied version of the unreleased Surf’s Up on a grand piano, Bernstein described it as being nothing less than the “the most brilliant piece of contemporary music [he’d] ever heard”.

This resonant endorsement from America’s most prominent composer blew minds, and not in a good way. According to an 81-page essay in the book The Dark Stuff, by the music writer Nick Kent, “Brian Wilson broke down there and then. Freaked right out and ended up phoning his astrologer, a woman named Genevlyn, who told him to beware hostile vibrations. So he stayed in bed for five days, eating candy bars, smoking pot and brooding to the sound of wind chimes.”

If you happen to be one of the people keenly anticipating the arrival of the documentary film The Beach Boys, available now on Disney+, please be advised that this remarkable account fails to occupy a single moment of its near two-hour running time. Never mind that in marrying wild acclaim – from Leonard Bernstein, of all people, not some stoned hack from Creem or Hit Parader – with crushing insecurity, the story handily typifies the triumphs and terrors running wild behind the group’s sun-kissed exterior. For the life of me, I cannot account for such an obvious omission.

While it wouldn’t be quite fair to accuse Beach Boys of entirely overlooking definitive and sometimes grisly details, it is right to accuse the film of seeking to place a positive spin on even the ugliest moments. Worse still, it seeks to imply that talent of the group’s members was, to some degree at least, evenly spread. But it really wasn’t.

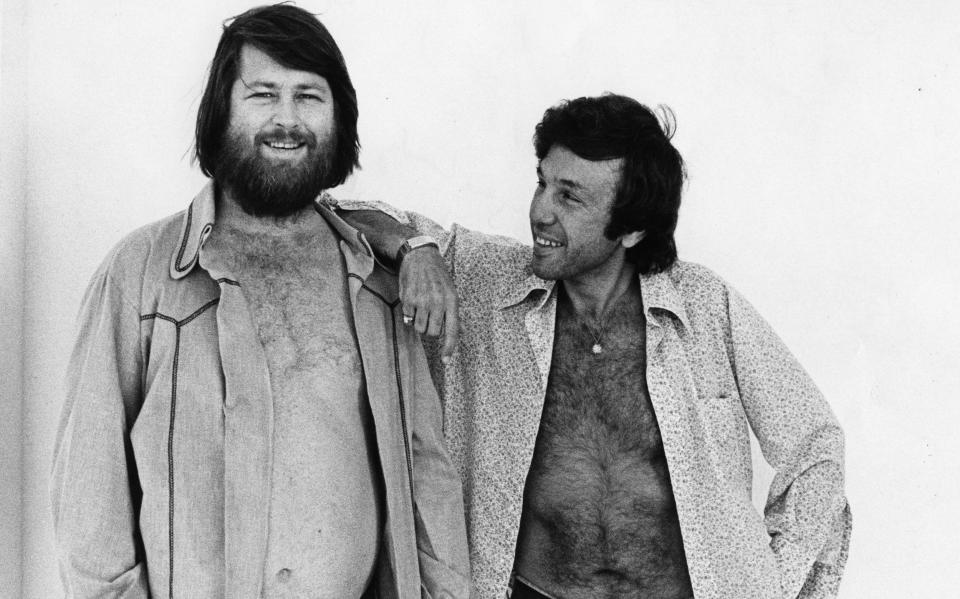

Without wishing to discard notable moments from younger brothers Carl and Dennis, I don’t think it’s a spoiler to note that it was Brian Wilson who shaped their scene. By dragging rock and roll from the American South to the West Coast, he even defined the modern image of California as a sun-kissed idyll ideated the world over. Beat that.

With its devious sleights of hand, though, Beach Boys is practically a magic show. It’s only in the credits, for example, that viewers who have just emerged from comas lasting half a century are informed that Carl and Dennis Wilson are long dead. There’s certainly no mention of the recent conservatorship request filed in a Los Angeles court by family members who described the now 81-year old Brian Wilson as an “easily distracted” man who is “unable to properly provide for his own personal needs for physical health, food, clothing, or shelter”. Not a word is said about the other times the courts have been asked to rule on who controls his life and estate, either.

Of course, any serious attempt to tell the full story of the life of Brian Wilson would require Beach Boys to clock up more episodes than Coronation Street. Sad to say, though, that the cutting of corners seems to be about more than merely saving time. In one particularly startling omission, the name Eugene Landy, the American psychologist who glommed onto his life, off and on, for three decades of coercive and sometimes brutal treatment, merits not a single mention.

Eventually disbarred from practising in the state of California, Landy charged up to $430,000 a year for his services, as well as a cut of publishing rights. At times, the dominance was total; he reportedly had a minion stood over Wilson with a baseball bat as he tried to write songs. His stricken patient once described the shrink as “my master”, before adding, ominously, that “a good dog always waits for his master”.

“I want to go places, but I can’t because of the doctor [Landy],” Wilson once stated in a revealing interview in Oui magazine. “I feel like a prisoner and I don’t know where it’s going to end… he would put the police on me and he’d put me in the funny farm.” Eugene Landy even ghost-wrote Wouldn’t It Be Nice, an autobiography from the early 1990s credited to Brian Wilson himself. In a fiercely contested field, it remains the most dishonest and depressing music book I’ve ever read.

The most generous interpretation regarding the chaos of the Beach Boys and their stricken artistic engine is that no one really knew what to do for the best. In the entertainment game, people rarely do. A more reputable psychologist than Landy once told me that “the creative mind is a vulnerable mind”, an evaluation which suggests that, for some, talent and instability are inseparable. The music industry doesn’t require people go mad, but it will certainly tolerate those who do so. Family life, meanwhile, is often less forgiving. In the midst of terrifying drug benders in 1970s, Brian Wilson’s wife insisted he live in the small changing room of their swimming pool so as to avoid contact with their children.

Possibly he was doomed from the start. Raised in the LA suburb of Hawthorne, his childhood home was a place of danger, oppression and alcoholism. Patriarch Murry Wilson was a frustrated but talentless songwriter whose blows to Brian’s head were so frequent as to be creditably identified as the reason he went deaf in one ear at the age of two. The father saw his son’s genius as a means of swapping his lot in the machining business for a hop with the rock biz jet set. When his tyrannical tenure as the Beach Boys’ road manager came to an end after a beating at the hands of singer Mike Love, in 1964, he retained control of the songs. The decision to sell the group’s publishing for a relative pittance saw his eldest son once more retreat to his bed in shattered dismay.

“You go through your childhood and you have a mean father that brutalises you and terrorises you – and Dennis and Carl – [and] he knocked the hell of out of us,” Wilson once said. “In fact, I asked myself, ‘What in the hell was that all about?’ A mean father who turned us into egomaniacs, ‘cos we felt so insecure our egos just jumped up. It was such a scary feeling.”

With the seeds of madness germinating early, he was certainly never in any kind of shape to deal with the demands of life on the road. The Beach Boys documentary mentions a nervous breakdown en route to a concert in Houston, in 1964, but fails to acknowledge several other acute episodes in its immediate aftermath.

Brian Wilson never enjoyed playing live; the studio was where he felt most alive. But when bandmates and executives from Capitol Records first heard the songs that would grace the Pet Sounds album, both parties were unconvinced. Despite being a masterpiece, the LP duly underperformed in the US charts.

In a field in which image and marketability are key, inevitably, the reluctance of music executives and creative dependents to fully support Wilson’s progressive instincts dealt a terrible blow to his already fragile sense of self-worth. Tellingly, as was the case with Leonard Bernstein’s remarkable endorsement, effusive encomiums proved equally damaging. When Paul McCartney (on whose talents the principal Beach Boy obsessed) opined that he sometimes believed that God Only Knows was the perfect song, its author swan-dived into yet another plummeting funk at the prospect of being a washed-up has-been who would never write anything as good again.

It should be borne in mind that some of the stories about the eccentricities of Brian Wilson are not that far removed from other “out there” artists and public figures from the laissez-fare 1960s and 1970s. As Carol Kaye, who played session bass guitar for the Beach Boys, told the writer Jeremy Gluck, “There’s a lot of slander going round even yet, many false things that never happened. So what if he was in his robe at his big house? Hugh Hefner lives in his robe. And so what if he wanted to record in the bottom of his empty pool? [Flautist] Paul Horn went to the pyramids for the same reason – great echo.”

Also, it wasn’t as if other members of the family didn’t exhibit their own alarming tendencies. After allowing Charles Manson into the group’s orbit, the always heedless Dennis Wilson (who died in 1983 as a penniless and homeless drunk and drug addict) earned death threats following the Manson Family murders in Los Angeles in 1969. Suitably spooked by the mayhem, brother Carl moved with his own family to his parents’ home, much to the alarm of his alcoholic mother. “I don’t know why you brought them here, son,” Audree Wilson whispered through a thick fog of whisky. “Those Manson people are bound to know our address too.”

Somehow, though, Brian Wilson stood out even in this deranged ecosystem. After filling a recording studio with smoke during sessions for the long-aborted Smile album, he believed he’d “mystically” managed to start a fire in a house two doors away. He once fled a cinema in panic after believing a character onscreen was talking to him directly in the voice of Phil Spector (another musical titan, this one equally troubled, on whom he obsessed). Believing himself underserving of happiness, throughout, he filled his life with troubled parasites and lost ne’er do wells whose sole purpose, it seemed, was limiting his own already diminished circumstances.

Then there were those who fixated from a distance. “Woodwork squeaks and out come the freaks,” noted the writer Bill Holdship in a 1995 article for Mojo magazine. “There are fans who feel it’s their role in life to protect Brian’s image. Something about the vulnerability of the finest Beach Boys music must act as a beacon for unbalanced people, fans who project their demands onto Brian in a way that’s unique among performer/fan relationships. When I did that 1991 cover story on Brian for BAM [magazine]… I actually received several death threats.”

Throughout it all, of course, whether he wanted them or not, he always had the Beach Boys. “They’re all I’ve got,” he once said. In a relationship that produced transcendental music and (often, at least) acute personal acrimony, they too were unable to wrest themselves free from the teat of Brian Wilson.

“They’re like birds with their mouths open for a worm,” he told Nick Kent. “They’re all so groovy, they’re real good at music, but they also know how to really f___ me over. Mike, Carl and Al [Jardine, the group’s rhythm guitarist] are the three guys that stomped my head in. Over the years they managed to stomp my brains out. They knew the secret formula [of] how to f___ Brian Wilson over. And they still do.”

Not that you’ll hear anything of this kind in the Beach Boys documentary, you understand. What you’ll get, instead, is Mike Love saying that “if I could, I’d probably just tell [the rest of the band] that I love them, and nothing can erase that.” The film ends with the surviving members greeting each other beneath a cloudy sky at the lip of the Pacific Ocean. As music fills the screen, one is left to wonder whether the singer took the opportunity to do even that.

The Beach Boys is available now on Disney+