Does the Maximalist Novel Still Matter?

The maximalist novel—also referred to as the “systems novel” or the “Mega-Novel”—towers, it looms, it stands upright on the bookshelf and intimidates readers, daring them to endeavor, to understand, to finish. These works began in earnest in post-WWII America, with novels like William Gaddis’s The Recognition and Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, and all share certain qualities (in Stefano Ercolino’s phrasing): length, encyclopedism, exuberance, polyphony, paranoia, ethical commitment, and hybrid realism. In other words, they’re long, dense, and ambitious, told from numerous points of view, interested in morality, awash in conspiratorial machinations, and framed in a narrative filled with over-the-top characters and unlikely scenarios.

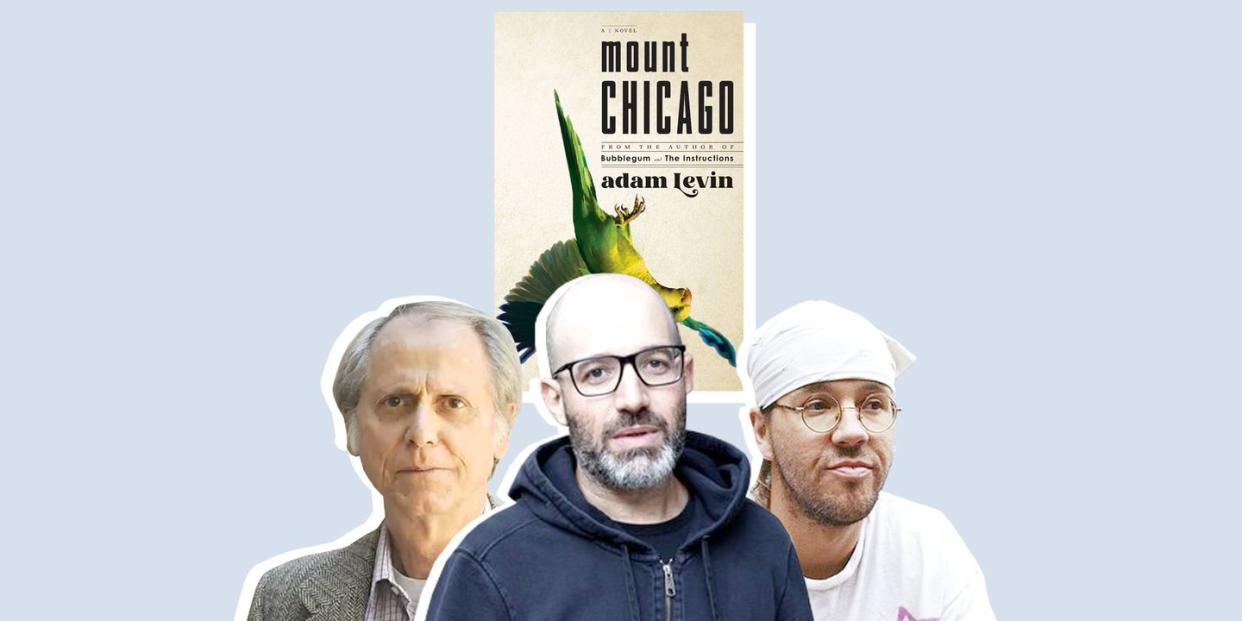

Adam Levin writes exclusively maximalist novels. His first, The Instructions, is a 1,000-page epic about, as Levin himself puts it, “a ten-year-old Jew who might be the messiah [and who] leads what is either a violent uprising or a terrorist attack or both.” Bubblegum, his second novel, takes place in an alternate world that never invented the internet. Now, we have Levin’s third novel: Mount Chicago, a 600-page satire about a comedian, a mayor, and an aide grappling with the fallout of a giant sinkhole swallowing an enormous chunk of Chicago. As with all maximalist novels, it’s stuffed to the brim with digressions, asides, varying points of view, nonlinearity, monologues, and all manner of other fictive techniques.

Once, the publication of a maximalist novel drew much publicity and attention, but now the market teems with them, to the point where a book like Matthew McIntosh’s 1,600-page theMystery.doc can come and go with little fanfare. The revolutionary techniques that distinguished them are now more commonplace, the public much more savvy to their narrative tricks and experiments. How can a novel be challenging if we already know the features that define it? You can only break a mold so many times before becoming a mold yourself.

But maximalism is not dead; it’s just being utilized for different ends.

There are a few scenes in Mount Chicago that speak to the issue of the maximalist novel's relevance today. The mayor’s aide mentioned above is a young man named Apter Schutz, and his sister Adi works for the publisher Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. She’s dismayed because her boss dismissed a novel called Money Changing Hands that she hoped to acquire; as he explains:

…it was just too long. The sales force, he insisted, would not get behind it; reviewers wouldn’t have the patience to contend with it; and according to the coverage Adi’d written of the book, it was neither young adult, nor dystopian, nor written by a person with an “interesting point of view."

When Adi protests that the novel’s point of view is in fact “truly unique,” her boss’s response is that the author “is a middle-aged cis white man who has published fiction for fifteen years. The world has heard from him before.” Moreover, he continues:

The world has heard from many just like him before many thousands of times. His point of view is therefore not interesting, would not be celebrated, would not, if we published his book in the current climate, lead to our house being celebrated, therefore would not garner any prizes, and so wouldn’t have a prayer of earning out.

Although the editor-in-chief admires “the ambition [the novelist is] showing… the market calls for someone with his background to be humble. The very times we live in call for that.” This scene, by the way, is set in 2015. Money Changing Hands is a maximalist novel, but the editor’s reaction to it goes beyond its style—it is not the maximalist novel that merits objection, but its author.

Mount Chicago opens with an “introduction” from Adam Levin himself, in which his intention is to separate himself from the text. He writes that although he and his characters may share some similarities, the novel is purely fiction. Despite his fiction being filled with impossible events and wild characters, readers still ask Levin whether his work is autobiographical. But what they’re often really asking for, he says, are Levin’s “credentials,” his “bona fides” to write about whatever it is he’s writing about. Does he have, in other words, the “authority”?

Levin, though, is “not interested in that stuff.” Here’s his take: “That I want the lies I write down to feel truer and realer than facts even as I admit they are lies via calling them fiction is, I believe, the only biographical information about me that a reader of my fiction should need to possess to be thrilled by my fiction.”

Levin refers to this as an “introduction,” but it’s given a title just as the other chapters are, and, moreover, throughout the book, Levin’s “I” interrupts the narrative a handful of times (as in, “…the information I’ve chosen to include in the paragraph above,” etc.), so it’s not a huge surprise when Levin turns up again with more “autobiographical” asides in the form of chapters. He mentions his previous novel Bubblegum, published in 2020 by Doubleday, which “had already been rejected by twenty-seven publishers” and would go on to be rejected “fifteen more times,” a process which left him “hopeless and embittered,” before the novel of course sold to a major publisher and was even printed with a jacket made to smell like bubblegum.

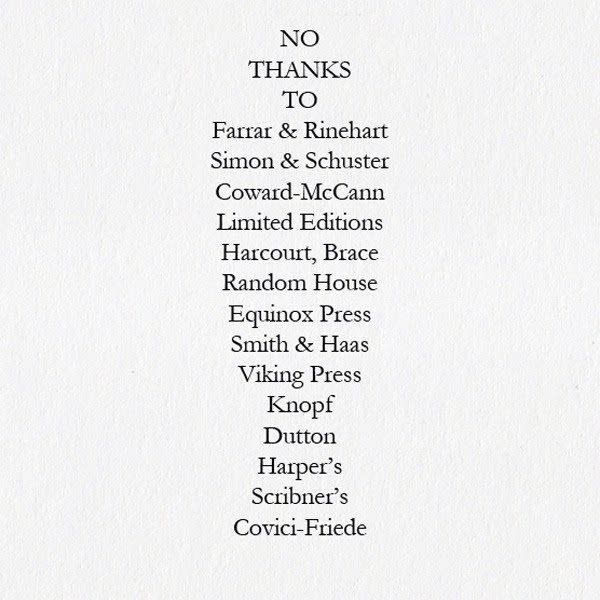

Clearly Levin is toying with the notion of metafiction—becoming a character in his own novel, but doing so as a faux ploy to assert authorial distance. But how does a reader not link these two mentions of much-rejected long novels by mid-career white men? Did any of the publishers who turned down Bubblegum say anything like Mount Chicago’s editor-in-chief did about Money Changing Hands? Did Levin feel “embittered” enough to exact revenge in the pages of his following novel? Writers have been known to do such things. After all, who can forget E.E. Cummings’s dedication page to his poetry collection No Thanks, which he self-financed after being rejected by numerous publishers. With the title, he expressed “no thanks” to:

If you’re wondering about the shape in which Cummings designed the dedication, it’s a funeral urn. Sick burn, Estlin.

The editor’s dismissal of Money Changing Hands is meant to reflect our contemporary political landscape—one in which white men are increasingly irrelevant, with the gatekeepers of art far more interested in work by historically marginalized voices—the very same landscape Joyce Carol Oates meant to reflect in her recent tweet about “a friend who is a literary agent [who] cannot even get editors to read first novels by young white male writers, no matter how good.” But maybe Levin including this scene stems merely from personal experience and is not meant as a takedown on “woke” culture?

Well, no. Because immediately preceding the Money Changing Hands scene is a general description of the present climate in which “any number of sharp, energetic, analytical people who seemed to earnestly wish to lessen their suffering and the suffering of others” stood next to “overwrought people who seemed to want to suffer…to be invested in their suffering,” the “safe-space people and trigger-warning people.” Then, there is a series of sequences in which young college students of the social justice warrior variety are lampooned for their over-reactionary sensitivity, pompous language, and smug sanctimony. There is an exchange between a group of Bernie Sanders supporters involving Apter’s idea to sell a daily calendar with positive and negative facts stated on each page to raise money for the Sanders campaign. The other members worry that they’ll inadvertently send the wrong message and appeal to the wrong demographic. Apter says, “In a word, who gives a fuck who buys it?” Either way, the money ultimately goes to their cause.

“It’s bad optics,” one kid named Braden remarks, to which another member (named Jessic) responds, “That was fucking violent, Braden.” When Braden expresses confusion, Jessic says, “It’s not my job to educate you, Braden!” Then, another member explains that Jessic has an “unsighted cousin” and that the phrase “bad optics” is “ableist as hell.” Some of the group react to Braden with “double-fisted finger-snaps,” but Jessic explains that they are “triggered” because Braden is clearly a “trauma tourist.”

Apter quits the group and spends some of his trust fund money to create his own “Real America” anti-woke calendar, which he then goads Jessic into publicly decrying, claiming that he (Apter) saw “a blue-eyed middle-aged prick” selling them, which turns the calendar into a huge success with Trumpers (Apter profits $1,350,000 by the end). Realist, straight-thinking, not-distracted-or-too-sensitive-about-identity-to-see-the-bigger-picture Apter pulls one over on those crazy liberals, all the while tricking the MAGA crowd into giving their money to Bernie Sanders.

Perhaps all of these opinions on wokeness are merely Apter’s and not Levin’s—after all, such collapsing of fiction and autobiography is what Levin began the novel by lamenting. But consider this: in the novel, we’re told about a long novel dismissed by FSG’s editor-in-chief purely because it’s too long and the author is a straight white male, therefore he should show more humility. Then, we’re shown a group of college students who embody that same philosophy saying absolutely ridiculous things about seemingly minor things. Then, Levin tells us about how his long novel was rejected by many publishers, which caused him to feel temporarily “embittered.” How do we not read these sections as his “takedowns” of wokeness? If they are not meant this way, then what other purpose can they possibly serve? If Levin thinks mockery of triggers and safe spaces and personal truths is funny or original or daring, then he is simply mistaken. Unless, of course, he really is as relevant and with-it as, say, Jeff Foxworthy.

And if it is meant as such, how then should we interpret Levin’s personal affront regarding his own fiction? In other words, how much is Levin bothered by wokeness because it’s “screechy and sanctimonious,” and how much because he, as a straight white male, believes he is excluded from it—or, worse yet, the target of it? And if wokeness aims to correct centuries of systems that privilege straight white men, is it possible for Levin to be both right and wrong?

Big, ambitious novels were once, by cultural default, mostly the realm of white men: from Gaddis and Pynchon first, then along to the likes of David Foster Wallace, Don DeLillo, and Neal Stephenson. Though there are of course numerous examples from the post-WWII era of similarly ambitious, complex, and exuberant texts by non-white-men— like Marguerite Young’s Miss MacIntosh, My Darling, or the novels of Marge Piercy—the twenty-first century has by comparison flourished with brilliant and thorny maximalist epics by women: Karen Tei Yamashita’s I Hotel, Zadie Smith’s White Teeth, Helen DeWitt’s The Last Samurai, Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries, Namwali Surpell’s The Old Drift, and Lucy Ellman’s Ducks, Newburyport, just to name a few.

Whereas Pynchon and company often focused their paranoid visions onto general concepts like addiction, entertainment, Americana, and the enormity of institutions, these maximalist novels by women have wrested the scope and techniques from the maximalist novel to aim them at hyper-specific, real-world issues: English colonialism in Zambia, the gold rush in New Zealand in the 1880s, the fight for civil rights in San Francisco in the 1960s, the thoughts of one woman living in Ohio. The Luminaries made Catton the youngest-ever winner of the Booker Prize. New York Magazine named The Last Samurai the best novel of the 21st century. Ducks, Newburyport won the Goldsmiths Prize. Maximalism is alive and well; it’s just under a wider and more eclectic stewardship.

In a Hollywood Reporter writers roundtable from 2019, the subject of “political correctness” came up, and one of the guests, Paul Schrader (famed screenwriter of Taxi Driver) suggested that “trigger alerts and all of that” are “bad for the creative process.” Then Bo Burnham said, “There’s a lot of elephants in the room right now, as there should be. Maybe there were elephants there the entire time… and I think it’s slightly unfair for us to expect the solution to these inequities to be perfectly fair.”

This is the bitter pill many white men find difficult to swallow. In order for space to be made for others, then space that before was given to them must be relinquished or shared. Moreover, equality isn’t just about replacing X amount of men with Y amount of women—or white people with POC, or cis people with trans people—but about deliberately carving out space that is entirely theirs.

As the above list of novels by women attests, publishers aren’t afraid of length or complexity or density; they are—at most—perhaps more selective about who gets that space, but nobody is telling novelists, men or otherwise, not to be ambitious, particularly if that ambition has something new to offer. Adam Levin’s handwringing over woke culture reads empty and shortsighted and personal not because he’s wrong, exactly, about the idea that men may one day lose what they believed to be their spaces; no, Levin’s satire of present-day culture strikes one as petty and limp because he’s wholly wrong about its severity. Many people on Twitter pointed out to Joyce Carol Oates just what an avalanche of debut novels by men have been published in the past few years, so I needn’t rehash those stats, but even if what Levin is suggesting were true—even if, in other words, publishers were uninterested in novels by white men—then so what? Isn’t that a business decision? Are we truly to believe that a publisher, owned by a corporation, would make acquisitions based purely on moral grounds? If the literary landscape was so anti-white guy that a company truly believed publishing a white guy would hurt their reputation or their profits, would that be considered political in nature? Or merely pragmatic?

Perhaps this isn’t about publishing at all, but rather the political reality these publishing choices are believed to represent. If publishers truly believed the public didn’t want a book written by a white man and made decisions based on that belief, then the issue is ultimately with the public, right? But when the scope of a grievance moves from a specific field to the general culture, the complaint feels all the emptier. I’ve never understood artists who gripe about audiences losing interest in their art. An artist can lament the changing of cultural tides, but to assert that a new lack of interest somehow indicts the public as dumb or wrong or short-sighted—to me, this seems the height of arrogance, a way of saying, If they don’t like what I make, then they have bad taste.

Of course, Levin’s novel doesn’t quite go so far as to explicitly state any of this, although it’s in that territory. But it’s certainly the case with many bellowing men who have become convinced that the only reason they aren’t successful is the world is dead-set against them. They’re so convinced, in fact, that they make it the subject of their art.

It's appropriate that Mount Chicago has a stand-up comedian (who’s also an award-winning novelist) at its center, because comedians are often the (unintentionally) funniest objectors to wokeness. There was even a 2015 documentary called Can We Take a Joke? entirely devoted to this subject (featuring Jim Norton, who dismisses PC outrage as “an attention-seeking device” before getting up on stage and performing for hundreds of people). Comedians famously have the tightest relationship between their work and their audience’s reaction to it; if no one laughs at a joke, comics usually cut it or rework it. In this way stand-up is a kind of collaborative form, with the audience functioning as a quasi-editor, telling the comic which jokes land and which do not. A young comic, after performing for a “PC crowd” that didn’t laugh at any of their jokes, would have left the stage thinking, I’ve got to be better. But some older, established, even famous comics seem to think, the audience needs to be better.

Readers are down for unwieldy fiction that wears its idiosyncrasies proudly. They’re not, obviously, exclusively interested in them, as they take a long time to read and require more mental focus than many people can often give to any endeavor, let alone pleasure reading. But that audience is there, and perhaps when confronted with two titles of comparable ambition, these readers may pick up the one not written by a dude, because as citizens of our culture, they’ve probably read one or more novels by dudes before. Novels are, after all, meant to be novel.

Artists should have integrity and not bow to every whim of the audience, but they should also have the integrity to change and adapt. They shouldn’t do so for mere survival or financial reward, but because the skill of not assuming that your way is the right way is a basic tenet of good art-making, particularly good fiction writing. Novelists tell stories that often feature many points of view, and the best ones don’t take hard and fast positions on them; rather, they seek the humanity in the polyphony, the unifying threads that connect us. Those threads are fluid, ephemeral, and capricious, and they move wildly over a vast existential terrain. Thus, they can only be witnessed by those whose point of view isn’t fixed. What better form to accomplish this than the maximalist novel?

This isn’t new at all. Jerry Seinfeld, himself a comedian who doesn’t like “PC” culture, still acknowledges reality from time to time. In a conversation with Ricky Gervias on SiriusXM, when Gervais suggests that there are jokes comics no longer tell because they might offend someone, Seinfeld says, “We’ve always done that. The court jester had to do that… The mental agility that is required to execute this job is an essential part of it. Comedians complaining, Oh I can’t do this joke because so-and-so will be offended? That’s right, you can’t. So do another joke. Find another way around it. Use a different word. It’s like slalom skiing; you have to make the gates.”

You Might Also Like