Eighty Years Later, Richard Wright's Lost Novel About Police Brutality Speaks Across Decades

In July 1941, Richard Wright, then America’s leading Black author, began writing the novel he felt was his masterpiece. Written “at white heat,” as Wright’s close friend, the Harlem Renaissance poet Arna Bontemps, described to Langston Hughes, The Man Who Lived Underground was drafted in just six frenzied months, with Wright rhapsodizing of the book, “I have never written anything in my life that stemmed more from sheer inspiration.” Wright saw The Man Who Lived Underground as a creative breakthrough: an allegorical and existential novel that stood in stark contrast to the literary naturalism of his name-making bestseller, Native Son. But despite Wright’s bullishness, The Man Who Lived Underground didn’t see the light of day in the form he intended. Following a crushing rejection from Wright’s publisher and a truncated publication as a short story, the novel was shelved for eighty years—until now.

At the time he was writing The Man Who Lived Underground, Wright's star couldn't stop rising. Native Son, published just one year earlier, was a national sensation, with critic Irving Howe proclaiming, “The day Native Son appeared, American culture was changed forever. No matter how much qualifying the book might later need, it made impossible a repetition of the old lies. In all its crudeness, melodrama, and claustrophobia of vision, Richard Wright’s novel brought out into the open, as no one ever had before, the hatred, fear, and violence that have crippled and may yet destroy our culture.” In his many books to follow, Wright laid bare the heinous oppression and degradation Black Americans experienced, inaugurating a tradition of protest literature that would inspire Black writers for decades to come. To this day, he continues to loom large in the American literary pantheon as a force of nature, lighting the way for writers seeking to question power and identity on the page. The publication of an undiscovered novel from an American master will always make news, but in the case of The Man Who Lived Underground, the novel’s resurrection raises powerful questions about the racist forces that conspired to bury it.

The Man Who Lived Underground is the blistering story of Fred Daniels, a Black man apprehended and brutally beaten by the police, who coerce him into signing a false confession for the murder of a white couple. Desperate to return to his pregnant wife, Daniels seizes an opportunity to escape police custody by fleeing into the sewer system, but soon enough, Daniels’ attachments to life above ground fall away. While taking refuge in an underground cave, Daniels tunnels into a church and various businesses; what he observes from the periphery of public life leaves him profoundly changed. When Daniels finally surfaces, eager to share his epiphanies with an indifferent world, the novel barrels toward a gut-punch conclusion. Eighty years after Wright drafted The Man Who Lived Underground and sixty years after his death, Library of America has resurrected the long-lost novel in cooperation with Wright’s descendants: Julia Wright, his daughter and literary executor, and Malcolm Wright, his grandson.

The novel’s path to resurrection began in 2010, when Julia Wright traveled from her home in Portugal to Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, where the majority of her father’s archive is held. There she uncovered The Man Who Lived Underground and concluded that it must be published, so startling was its contemporary relevance to an America still riven by rampant police violence.

“Julia was the catalyst behind bringing this project into the light of day,” said John Kulka, editorial director at Library of America. “She recognized long ago the significance of a novel-length version of this story, with its graphic depiction of police brutality against a Black man. She also recognized the artistic merits of the novel apart from those of the short story.”

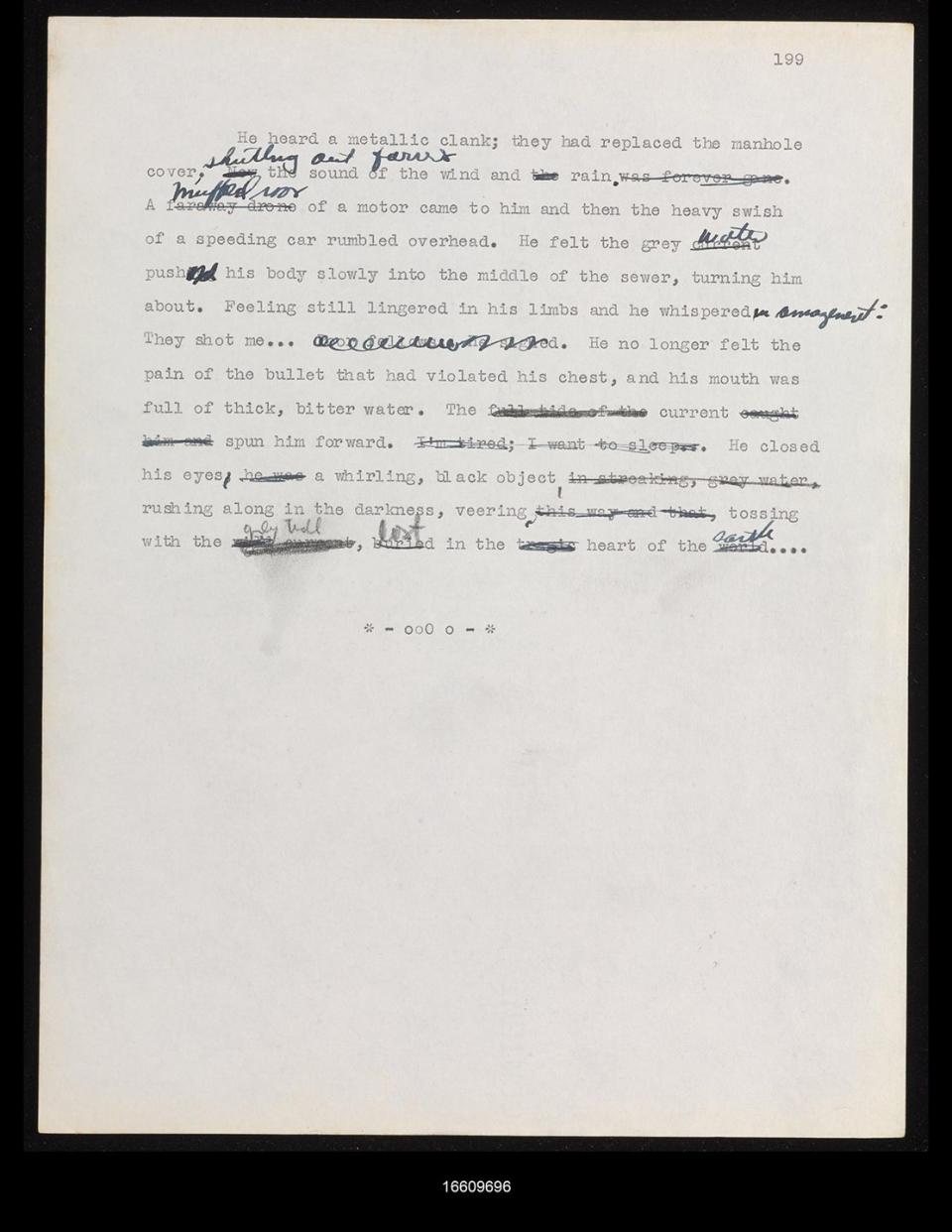

Yet shepherding The Man Who Lived Underground into the twenty-first century wasn’t so simple as salvaging a pristine manuscript from a desk drawer. Between the Wright archives at Yale and Princeton, six different typescripts existed, some featuring handwritten emendations from Wright himself; this led to a slow, painstaking editing process for Kulka, who examined and collated the various typescripts to establish the final text. These typescripts reveal not only Wright’s genius at work, but the dispiriting publication process that long buried the novel.

In December 1941, Wright’s agent, Paul Reynolds, submitted The Man Who Lived Underground to Edward Aswell, Wright’s editor at Harper & Brothers (now HarperCollins), who declined to publish it. Why Aswell rejected the novel remains uncertain, but one typescript provides clues. The copy Reynolds submitted to Aswell, now held at Yale, features marginalia from reader Kerker Quinn, the editor of the prestigious literary quarterly Accent, who noted the brutality of the scenes in which Daniels is tortured by the police, describing them as “unbearable.” Kulka believes that the novel was “too hot to handle”; similarly, Wright’s biographer, Hazel Rowley, argues that the novel was rejected because it “portrayed all too clearly the arbitrary ‘justice’ of the world.” Though it seems clear that the novel’s scorching truths scandalized the white imagination, so too must it be noted that The Man Who Lived Underground was not the chaser to Native Son’s megawatt success envisioned by Reynolds and Aswell, who were eager to capitalize on their star author’s growing acclaim.

“Going back to the winter of 1941, we have to remember that Richard Wright was a rock star,” Kulka said. “He was Harper & Brothers’ most important author, and the leading Black writer in America. Native Son was a huge success for Harper & Brothers, selling over 215,000 copies in its first three weeks on shelves. Reynolds and Aswell were very concerned about protecting their investment in Wright. They didn’t recognize this short, strange, allegorical novel as a worthy successor to the bestselling Native Son.”

After Aswell’s rejection, Quinn published two short excerpts of The Man Who Lived Underground in Accent, each pulled from sections of the novel set in Daniels’ underground cave. In 1944, a novella-length version of the story, with the police brutality scenes excised, was published in an anthology titled Cross Section, which also featured new writing from Shirley Jackson and Arthur Miller. When Wright’s short stories were anthologized in Eight Men in 1961, a similarly truncated version of The Man Who Lived Underground made the cut. Julia Wright described this series of alterations as “dismemberment,” while Malcolm Wright likened them to censorship.

“I have absolutely no doubt in my mind that someone took a look at this novel and said, ‘This isn’t going to fly. I want this author to publish, but not like this,’” Malcolm Wright said. “This is the kind of velvet violence that happens behind closed doors. Not just when we publish books, but when we have one-on-one discussions about race in America. We have to learn to talk about it. The places where we refuse to go perpetuate the issues.”

This was not the first time Wright was pressured to sanitize his vision, nor would it be the last. In 1940, the then-all powerful Book of the Month Club agreed to make Native Son a Book Club selection if Wright would agree to tone down language the organization considered to be graphic. Wright also agreed to excise an early scene in which Bigger Thomas, the novel’s antihero, masturbates in a movie theater while viewing a newsreel about Mary Dalton, the socialite he will later go on to kill. When Black Boy was later published in 1945, Book of the Month Club again agreed to select the book, on the condition that Wright essentially cut the text in half. Book of the Month Club was eager to feature Black Boy’s first half, in which Wright recounts his childhood and adolescence in the Jim Crow South, but they refused to spotlight the second half, in which Wright relates his move to Chicago and growing involvement with the Communist Party. In 1991, Library of America published, for the first time, the unexpurgated versions of Native Son and Black Boy, restoring the texts to the condition Wright intended.

“There’s no question these books would have looked different if Wright had been allowed to publish them the way he wanted to,” Kulka said.

As this long-delayed novel arrives in its original form, it invites us to reconsider our understanding of Wright’s life and legacy. Kulka describes The Man Who Lived Underground as “the missing link” between Native Son and The Outsider, Wright’s high-flying 1953 novel about a Black man’s disastrous search for existential meaning, noting that The Man Who Lived Underground shows Wright developing the “allegorical method” he would later employ in The Outsider. Accompanying Library of America’s full-length edition of The Man Who Lived Underground is “Memories of My Grandmother,” a second previously-unpublished work from Wright, which Kulka describes as “a significant addition to the Wright canon.” Intended as a preface or afterword, Wright structures the essay to explain his methods of composition and inspiration, which included his grandmother’s fervent Seventh Day Adventist faith, surrealism, blues lyrics, and the Invisible Man film series of the 1930s. So too does the full-length publication of The Man Who Lived Underground reveal the shockwaves the novel sent through the literary world—namely in the life of Ralph Ellison, a friend and contemporary whom Wright selected as his best man at his 1939 wedding.

“The Man Who Lived Underground changes the way we see the canon of American literature,” Kulka said. “The novel-length version reveals just how powerfully the story influenced The Invisible Man, another novel featuring an underground protagonist. When Accent ran two excerpts of The Man Who Lived Underground, Ellison felt compelled to write a short note of congratulations to Kerker Quinn. Looking at the typescript of the novel, Wright actually used the words ‘invisible man.’ The influence on Ellison was profound.”

For Malcolm Wright, The Man Who Lived Underground shades in decades of family lore, offering a fuller understanding of Wright’s seismic decision to expatriate in 1946 (a perceived desertion of Black America for which some critics never forgave him). Born fourteen years after Wright’s death, Malcolm Wright, now a filmmaker whose “secret and not so secret” aspiration is to adapt The Man Who Lived Underground for the screen, describes his grandfather’s works as his “biggest window on the world.” Though it was not apparent when he first read the novel at age sixteen, he now understands The Man Who Lived Underground as a foundational text in his family’s history.

During the book’s composition in 1941, Wright and his wife were expecting their first child (Julia Wright), much like Fred Daniels. Though he lived in New York City, where he hoped to experience more equitable treatment than he had in Chicago or in the South, Wright continued to be targeted by virulent racism, with taxicabs declining to transport him and Manhattan restaurants refusing to serve him. Years later, he would tell Aswell, “In all of this pointless racial business, I found that my being a rather well-known writer did not help me any. In fact, it hindered, for many whites felt that by refusing me they were ‘putting me in my place.'” Weary of American racism’s daily dehumanizations, Wright began to contemplate leaving the United States and settling his growing family elsewhere.

“Think about Richard considering making this leap away from everything he’s ever known,” Malcolm Wright said. “He did this before, when he left the South and struck up in Chicago. But the leap doesn’t get easier—each time, it’s like facing a black hole. I think that Richard, while writing this novel, was allowing himself to stand in front of that fear. Through imagining what happens to Fred Daniels in the underworld, he explored it and he embraced it. The exploration of that freedom, in my imagination, was probably exhilarating for Richard. I feel that exhilaration when I read it. Suddenly all that oppressed Fred Daniels is gone. Time falls away. The values of society fall away. He's able, for the first time in his life, to make his own path. Beyond the question of race, I think that theme is universal and transcendent. It's the reason why we love prison break movies. It's the reason why we’re so exhilarated when we see someone explore the edges, strike out alone, and bring back something unknown.”

As The Man Who Lived Underground surfaces into the light of day, it’s not lost on anyone involved in the novel’s resurrection that the world it rises to meet is so different from the world its author lived in, yet so very much the same. Considering how his grandfather would react to the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement and the global groundswell of activism following the murder of George Floyd, Malcolm Wright is confident that Wright would be heartened, but consider the work ongoing.

“Richard was a big picture person,” Malcolm Wright said. “I think he knew that some form of progress was inevitable. I don’t think he would be terribly surprised to see that the country has been able to awaken—in fact, he would have been extremely pleased—but he had a strong understanding that the demons we face run deep. I think he would say, ‘Let’s keep working. We’re not there yet.’”

In the summer of 2020, Black Lives Matter demonstrators marched past Wright’s onetime Brooklyn home at 11 Revere Place, where he drafted The Man Who Lived Underground during those fateful six months so very long ago. If the throngs of activists in the streets are any indication, it seems we may finally live in a world ready to receive Wright’s message.

“We’re becoming aware of the bubbles we live in because of social media and online culture, but in the United States, we’ve always been in a bubble,” Malcolm Wright said. “Becoming aware of that is the first step to growing out of it. Maybe the publication of The Man Who Lived Underground is a sign of a willingness to expand—to look at the pioneers among us, who realized long ago that there was a bubble we needed to grow beyond. It’s never too late to start paying attention to what those pioneers had to say to us.”

You Might Also Like