"An era of decadence began with a hope, passion and joy centred on music": how Los Angeles in the 1980s became the hair metal mecca

No man is an island, and (almost) no band is without its imitators. Proof positive: the 1980s Los Angeles rock/metal scene, long the scintillating and sometimes scandalous topic of books, documentaries and nostalgic rear-view gazing from those who were there – and those who wished they were. Hearing the siren-call of record deals and fame, not to mention girls and booze by the gallon, Poison were early transplants to the West Coast scene, driving from Pennsylvania to LA in 1983.

From the early 80s onwards, imitators, each version paler than the last, flocked to the Strip. The 1986 release and rise of Poison’s Look What the Cat Dragged In inspired another tsunami of hopefuls. So many, in fact, that by the early 90s even many of those who cared most about heavy music were ready to call it: “Grunge killed hair-metal!”

Frankly, by 1991 it deserved to die. The Strip metal scene had been limping along for years, the influx of acts from all across the country proving themselves umpteenth-generation photocopies of the local originators. Thanks to Van Halen, initially a local backyard party band who made it big in 1978, a ton of kids growing up in SoCal thought they could be the next Van Halen. Would-be guitar innovators and flamboyant frontmen proliferated.

The seeds of the scene were a suburban Valley bumper crop of rabid music fans who grew up listening to Deep Purple, Aerosmith and Rainbow on vinyl with friends, ditching school and driving around sunny SoCal in vans with radio stations KLOS and KMET cranked up, and drinking beer. The driving was too often done drunk and with powder under noses, hair spray always at the ready. An era of decadence began with a hope, passion and joy centred on music.

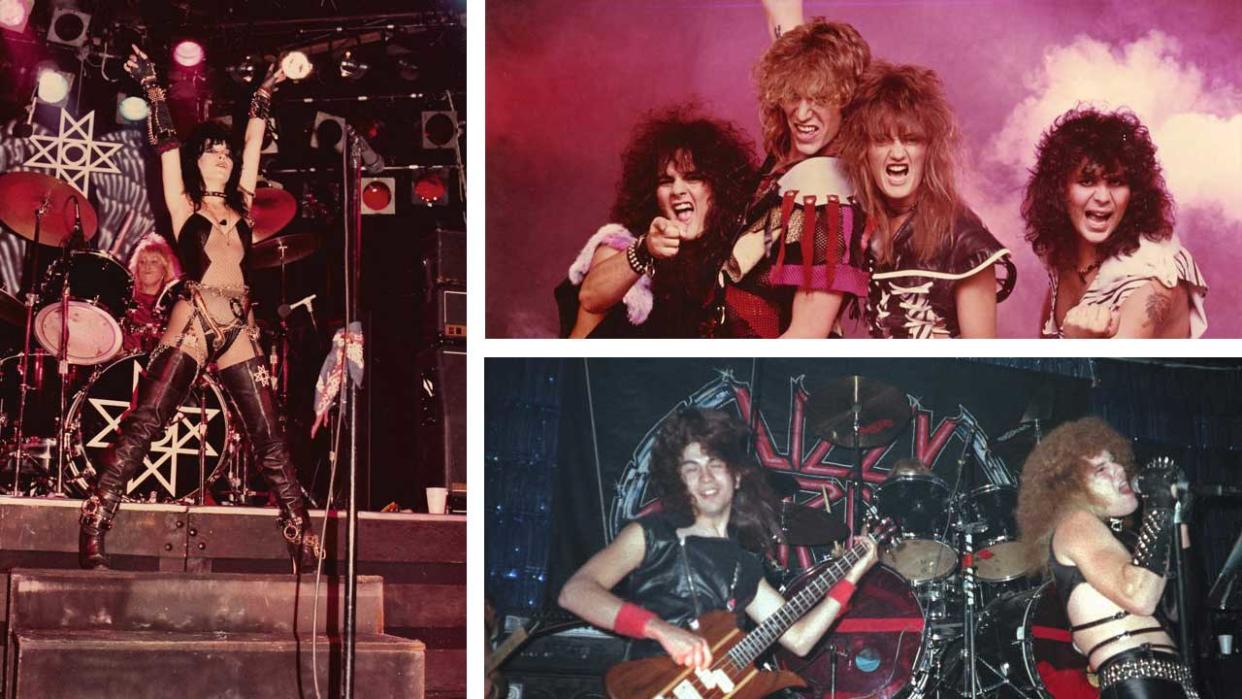

The Los Angeles strain of heavy metal emerged from unheralded locales such as Altadena and Lakewood, from the musically fertile San Gabriel and San Fernando Valleys and the South Bay, not to mention Orange County. Legions of high-school kids packed backyard parties to watch their schoolmates’ bash through freshly minted classics by Black Sabbath, Scorpions, Iron Maiden and Judas Priest. California’s own heavy metal parking lots were outside the mighty Forum awaiting Led Zeppelin or Kiss, and those same increasingly long-haired kids filled the 500-seat Starwood for local heroes like London, Snow, V.V.S.I. and Dante Fox.

Sure, some actually made it: M?tley Crüe, Quiet Riot, Ratt and Guns N’ Roses, to name a few. But for every band that succeeded, dozens didn’t. That’s not to say the music or stories from these line-ups were any less than those by the platinum superstars they aspired to be. The fans were still rabid, the memories made still shining, or shocking, the hope springing (almost) eternal.

Sometimes it was simply timing or luck that derailed a band’s ascension, the brass ring always just out of reach. Between the grooves of every hit record are the sagas and songs of the lesser-knowns. Van Halen shout out ‘Top Jimmy’, a local blues player, in a song on their 1984 album; most smaller-than-stadium bands don’t get even that kind of recognition.

As the original crop of 80s rock bands and fans get nostalgic and younger rock fans search for lost gems, compilations like Bound For Hell: On The Sunset Strip are there to fill the void. The album’s more than 20 bands, including Steeler, Jaded Lady, SIN and Angeles, are only a few of the scene’s lesser-known but not-forgotten line-ups who are only too glad to share songs and set the record straight.

Those of a certain age will recall that back in 1982 Ozzy Osbourne bit the head off a bat; his virtuoso guitarist, Randy Rhoads, died in a plane crash; The Who kicked off their first farewell tour; future Queen singer and American Idol star Adam Lambert was born; John Belushi died… Without the internet or cell phones to fuel the mythology, Southern California was bearing witness to an aural and visual tempest comprised of screeching FlyingV guitars, double bass drums and sky-high teased hair.

These bands sang salacious rock songs, mostly about girls, partying and… more girls. It wasn’t music purveyed by poseurs. In their stiletto boots and ripped-up fishnets, the leading lights of a movement walked it like they talked it. And songwriters in jeans and T-shirts played and partied cheek-by-jowl with performers in leather and codpieces.

The Sunset Strip sang an irresistible siren song to young metalheads, the stretch from Tower Records at Horn Avenue west to the Geffen Records headquarters at Doheny their club-studded stomping grounds. The Strip at large also counted the Troubadour among its cornerstone clubs, as well as the Valley’s Country Club, Perkins Palace in Pasadena, and a constellation of outlying venues.

The Rainbow and Gazzarri’s were ground zero, both inside and on the sidewalks out front. Dudes handing out flyers to gaggles of girls tottering on sky-high pumps was at once a conversation-starting mating dance and a sales-pitch mass ritual, lubricated by beer, bravado and blind ambition.

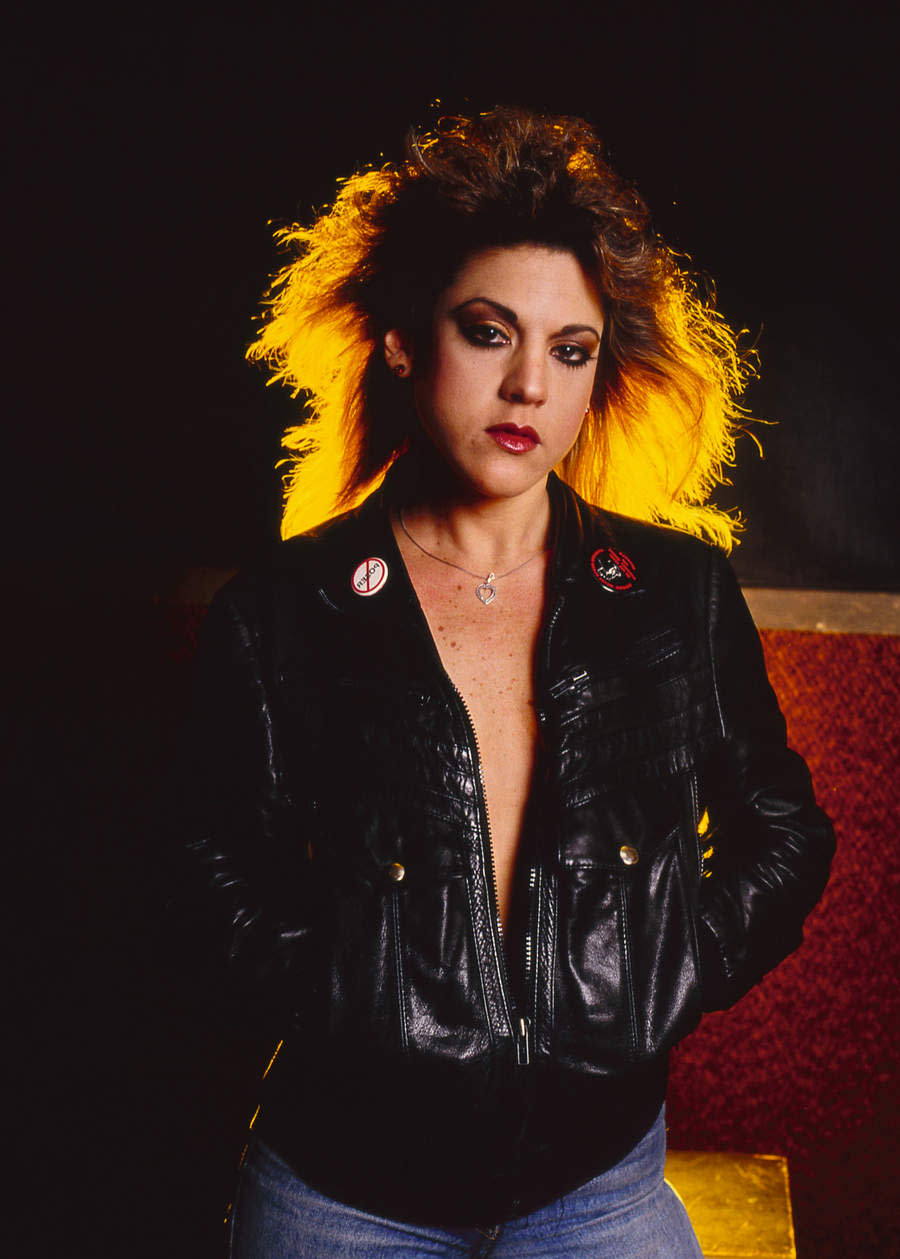

For the most part, the Sunset Strip was no less a woman’s workplace, although there was an undeniable dearth of women in bands. Locals such as (transplanted from Washington) Ann Boleyn of Hellion and Bitch’s Betsy Bitch reaped an array of rewards, feeling empowered on stage, earning the respect of fans and male co-combatants, collecting the horror stories of unpaid door takings and unscrupulous management that were common to all.

Sure, the songwriting rarely offered Dylanesque gravitas, but that was of a piece with the music. And as such it was easily scoffed at by those not into heavy rock’n’roll and its trappings. On the other hand, it made for a colorful and fiercely loyal core group, bonded by a certain outsider status. Fiery, sacrilegious stage shows flipped the bird to 60s hippies and 70s soft rock. It spoke to and of a deliberately chosen lifestyle. It was serious fun and a deadly serious vocation for thousands. And it generated major money for the lucky handfuls of bands who broke big after scoring a coveted record deal; it made millionaires out of M?tley Crüe and Poison.

Built before heavy metal splintered into a million subdivisions, rabid fan bases endure even 40 years on, allowing the fortunate few ongoing careers to go with faded photos of their skinnier Spandex-clad selves. Egos need to be fed. And there were egos – massive, laughable egos. Documentaries like The Decline of Western Civilization Part II: The Metal Years and mockumentaries like This Is Spinal Tap examined and skewered LA glam specifically and the delusions of heavy rock in general.

Players went shamelessly, promiscuously, shuffling lineups incessantly, hoping to hit that perfect combination of riffs, looks, audacity and timing. Near-hits piled atop long misses, talents and train wrecks alike got famous, or moved on, or gave up, or refused to ever, ever stop even when the lights went down. But the cyclical nature of music could not be stopped. Pop-metal bands from elsewhere playing in the ‘hair-metal’ garden – say, Trixter, Baton Rouge, Sleeze Beez – all released records in 1990, but despite a hook or three the sound and image was played out.

The scene as it had been in the youthful half of the 80s was on life-support. And if some of the bands that moved to the city circa 80 or ’81 felt unwelcome at first, it was nothing compared to the arrivals of ’87 and onward, in search of fame, fun and fortune, the music itself playing second fiddle. The repeat MTV Buzz Bin sea-change of Smells Like Teen Spirit was just a Nevermind nail in a Cherry Pie coffin.

It’s been suggested that AIDS played a part in the scene’s demise, that the lethal realities of sex and drugs had a chilling effect on the scene and its devotees. How chilling, exactly, is unclear. Rather, times change, tastes change, and both fans and record companies were ready for something new and fresh, even if it meant taking a hard look at all the fun everyone was having. Armies of Sunset Strip-styled bands – wherever they’d popped up on the planet – had had their time under the spotlights or lit by flaming pentagrams. A new generation had arrived to take its rightful place in music’s evolution.

The book Bound For Hell: On The Sunset Strip collects a rogue’s gallery of integral entries to the vital early Los Angeles scene. Some came from other states, most line-ups are homegrown. One guitarist might remember every detail of every show and drag out the set-lists to prove it, while his drummer’s memory is like a worn-out Dio cassette stuck in a Camaro’s tape deck.

Was there a unified sound to that first wave of Los Angeles metal bands? One LA native suggests that while a lot of musical influences came from the UK and Europe, for some reason the LA bands didn’t sound like their inspirations.

“In some weird way,” he mused, “I guess it kind of created its own sound, if you will, and it became the LA sound.”

What is certain, though, is that every band loved the music they made, and believed in it, as they’d tell you, “a hundred and ten per cent”. They made lifelong friends. They wax nostalgic about the times, their fans. The stage brought out a self-confidence that only a few years previously was lacking in the unasked-for role of a high-school geek.

With the halcyon days now fading in the rear-view mirror, “We’re all like high-school buddies who survived graduation, so to speak”, one Sunset Strip survivor opined. “We’re all the best of friends with all those guys in that fraternity, but at the time it was very competitive.”

Perhaps it’s David Lee Roth who best summed up the rise and fall of the Strip, on Van Halen’s 1981 album Fair Warning: ‘Change, nothing stays the same. Unchained, yeah you hit the ground running.’

Bound For Hell: On The Sunset Strip is available via Numero.