Even If I Can't Be With Family for Thanksgiving, I Can Be With Their Food

I cried a little bit last week. Not an earth-shattering cry or anything, but a good ol’ fashioned “sit in a room by yourself and let the tears come as they will” cry. I was supposed to go home and visit my family in Tennessee back in March; it was going to be the first time my boyfriend Andrew met my parents. But that got pushed to June, and then October. Rescheduled plans started to look like that cliché movie sequence where calendar pages dramatically fall off the wall. The latest visit was penciled in for Thanksgiving, but it soon became evident that Thanksgiving—like birthdays, unfortunately timed weddings, and the Fourth of July—would go in the way of cancelled plans.

Andrew and I pivoted and decided to host a Thanksgiving for friends in Brooklyn, but even that was called off. The risk wasn’t worth the reward, which means the holiday intended as a celebration of people and thankfulness will instead be me, my boyfriend, and a cat coming up with inventive ways to eat the 13-pound turkey I impulse-bought in a fit of blind optimism. That’s enough tryptophan to stop a rhino, and I don’t even like turkey. So, fine. I’ll admit it. I cried. Cried because this year has been a lonely road and cried a little bit for how much turkey we’d be stuck with. Cried because I miss my family.

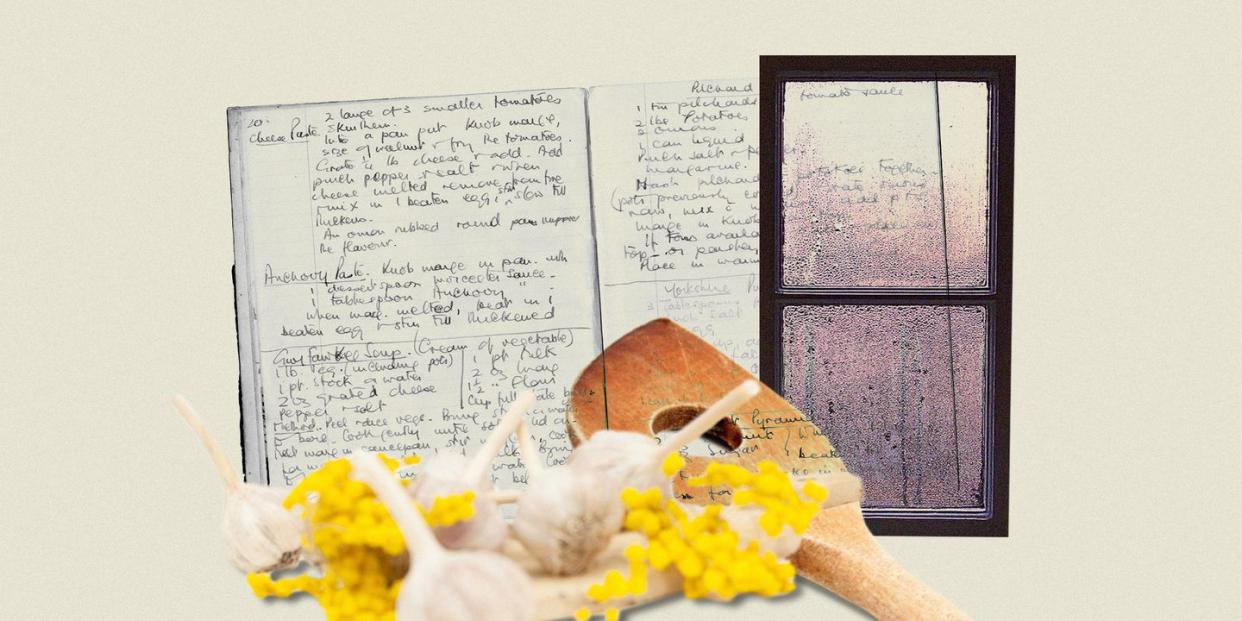

But mid-cry, I looked up and remembered this red book sitting on the shelf above my computer. I pulled it down and flipped to a page somewhere in the middle. I call it my food journal, but it’s really just a diary of handwritten recipes from my family, transcribed exactly in their voices with their measurements. I started it in April, when everyone else was making sourdough starters. I wasn’t interested in bread; I don’t have the patience for it. But for years, I’d meant to ask my parents for the recipes that defined my childhood. I’d planned to do it this past Christmas when I was home last, but I forgot. You always think there’s time later, and then you end up stuck in place for a whole calendar year.

So instead of waiting any longer, I resolved to make it a habit to call home—something every mom has been asking for since Alexander Graham Bell got handsy with a rotary dial. I’d ask my mom if she had 15 minutes to relay everything that goes into her fried chicken breading. I’d bother Dad for his secret chess pie recipe. And now, months later, I’m left with a whole collection of recipes that require a “good pour” of hot sauce or a “portion of dough the size of a cathead.” It’s written in our language.

My whole life, food has been a fifth member of our family. Even with two working parents, even if we didn’t sit down to eat until 10 at night, every meal felt intentional. The way you season a piece of meat or flavor a pot of greens says more about your family than any ancestry tree could. And though we didn’t always have the finest cut of steak, we played with flavors and spices, turning a deer ham into something better than filet mignon. Thanksgiving was weird in that way: fried squirrel next to wild turkey, and far too much food for a table that was usually only set for my mom, dad, brother, and me. But that’s how we celebrated—plates with impressionistic deer printed in the middle, filled to the edge with jellied cranberry and deviled eggs. The four of us, miserably full from our own creations.

People talk about Thanksgiving like it's a bloodsport, where families converge to throw down at the dinner table. I don’t agree with everything that my dad believes, God knows that. But we all have always shared respect of food, Thanksgiving or not. And while nothing could replace actual family, there sure were a lot of antidotes for lonesomeness in the 40 pages of that red journal.

Flipping through it, I knew good and well I could make a more appropriately sized Thanksgiving meal for two people this year. There was also the option of ordering out, because, hey, it’s New York, baby. But isolated and irritated heading into a holiday that’s predicated by the gathering of family, however you define it, I was drawn in by the Thanksgiving staple that is my mom’s Velveeta mac and cheese—practically a brother to me at this point. Sitting alone with the journal, I announced to myself, “Fuck it. I’m making the whole thing.” The mac and cheese, the other sides, the 13-pound turkey. There may be no squirrel (Dad said, “New York squirrels are probably too greasy,” anyway) and there may be no deer, but there'll still be plenty.

I started planning the meal out. The macaroni and cheese will take years off your life. A couple pages back are my dad’s mashed potatoes, akin to a happy polygamous marriage of butter, whole milk, and potatoes. Flip a few pages the other way, and you’ll find the cornbread my mamaw used to make. All in all, I decided, it would take about six hours, four sticks of butter, and a couple bottles of wine to create this feast. I announced my plan to Andrew, who looked as concerned as he was excited for what would appear on the table come Thursday. And I know I’ll be tired when it’s all said and done, but we’ve all been so tired anyway. At least I will know it was of my choosing, guided by the words of people who I can’t be with right now.

On Thanksgiving, when I’m sautéing up the green beans, I’ll ask Andrew for a couple fingers of grease. He won’t know what that means at first. But in a year when he can’t meet my family, there are recipes. Weird instructions. Vague measurements. And that’s about as close as you can get to the real thing.

You Might Also Like