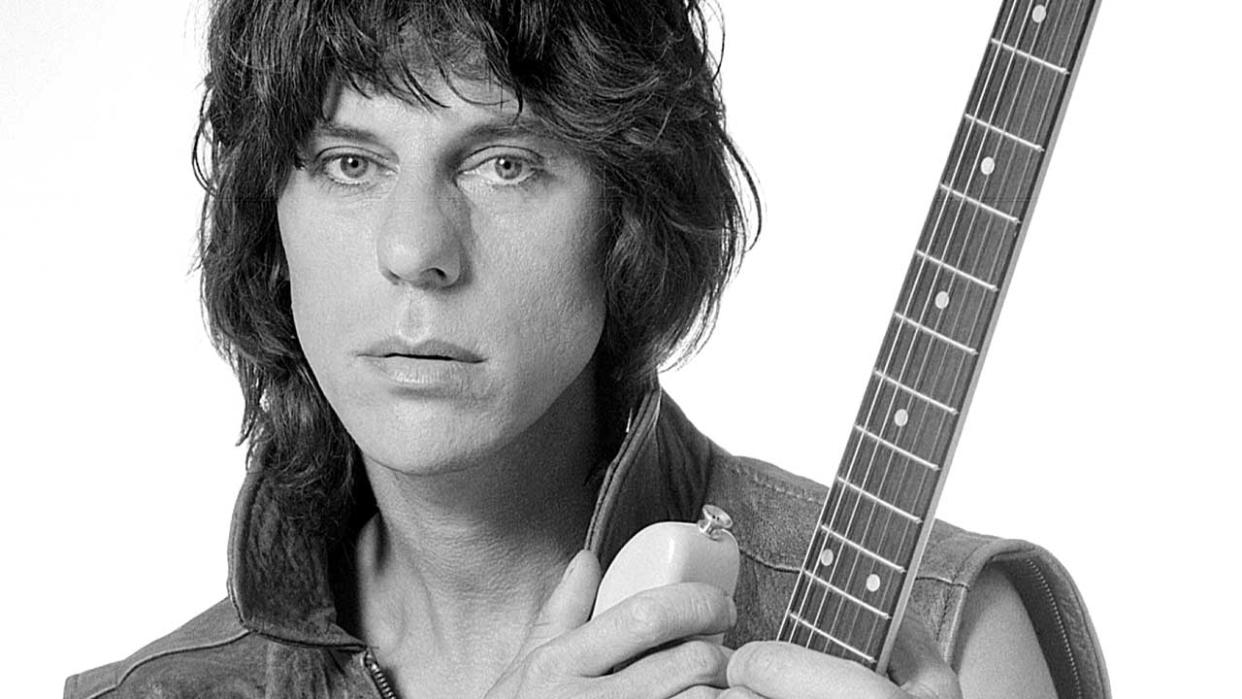

"Every single note he played could kill me with its beauty": Celebrating the life of a man regularly described by his peers as the greatest guitarist of them all, Jeff Beck

It wasn’t the number of records or concert tickets that he sold, and it certainly wasn’t his rock-god image that defined Jeff Beck – although he was plentifully endowed in all these departments. Rather, it was the unique depth and durability of his artistry that elevated him to the status of perhaps the best electric guitarist the world has ever known – and certainly the best over the distance.

Rather like Pelé or Michael Jordan or Roger Federer, Beck transcended statistical measures of greatness, to arrive at a state of grace where it was his peers who most enthusiastically acknowledged his supreme skill. David Gilmour called him “the most consistently brilliant guitarist”. Brian May declared himself to be “absolutely in awe of him”. And, as Steve Lukather put it, “No one will ever come close [to Beck]. One note is all he had to play and it was game over.”

“You’d listen to Jeff along the way and you’d say: ‘Wow, he’s getting really good,’” recalled Jimmy Page, when he was inducting Beck into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame (for the second time) as a solo artist in 2009. “Then you’d listen to him a few years later and he’d just keep getting better and better and better. And he still has, all the way through. He leaves us mere mortals just wondering.”

Given his generally robust condition and enduring presence among the classic rock greats, Jeff Beck’s sudden and unexpected death in 2023, from bacterial meningitis at the age of 78, cast a long shadow over the rock world and threw a new light on a career of sometimes explosive and always surpassing excellence. He had just finished one of his more industrious years, undertaking a lengthy stretch of dates in the UK, Europe and North America throughout 2022, promoting what turned out to be his final studio album, 18, released in July the same year.

The album was recorded with Johnny Depp, who joined him on tour – a collaboration that certainly underlined Beck’s continued willingness to offer unexpected challenges to his audience. He also performed a run of shows with ZZ Top and singer Ann Wilson which elicited more traditionally outstanding performances from all concerned. Check out the footage of Beck performing Rough Boy with ZZ Top, and marvel at how he converts a southern rock ballad into music of the spheres.

Thanks to his pioneering work in the 1960s with The Yardbirds and his own group, Beck was anointed alongside Page and Eric Clapton as one of the ‘Holy Trinity’ of English guitarists – all three of whom had passed through the The Yardbirds. But while Clapton subsequently retreated from his role as a virtuoso steeped in the blues tradition, and Page channelled the overwhelming majority of his energies into driving the Led Zeppelin juggernaut (which ground to a halt after the death of their drummer John Bonham in 1980), Beck never stopped his quest for mastery over all aspects of his instrument and new avenues for expressing himself on it.

Beck was a guitarist in the purest sense. He was not a singer (apart from his reluctant vocal performance on his 1967 hit single Hi Ho Silver Lining, and one or two tracks tucked away on his solo albums). And although he scooped up a few songwriting credits here and there – particularly on the Jeff Beck Group album Rough And Ready (1971) and his 2016 studio album Loud Hailer – he was not a lyricist and never really a songwriter per se.

His guitar was his voice and means of expression. His core creative mission was to attend in infinite detail to the touch, the sound and the playing of his instrument to ever greater degrees of excellence. You could describe the process as a lifelong spiritual quest or calling that he pursued, while leaving “mere mortals”, as Page put it, to wonder how he had done it.

Geoffrey Arnold Beck was born and grew up in Wallington, Surrey, where as a teenager he learned to play on a borrowed guitar. His primary influences were American blues guitarists such as Muddy Waters and Buddy Guy. Once he had got hold of an electric guitar, he started off with a brief stint in Screaming Lord Sutch And The Savages before joining local R&B group The Tridents.

His big break came when his 21-year-old friend Jimmy Page – who was already making a name for himself as a session musician – recommended Beck as the replacement for Eric Clapton in The Yardbirds in 1965, just as the band embarked on a string of trans-Atlantic hits starting with For Your Love.

Although he was a key figure in the British blues boom, Beck took an early exit from what Carlos Santana called “the BB King highway”. Beck’s first single with The Yardbirds, Heart Full Of Soul, was notable for the Indian-influenced bends in the guitar hook which he provided (which was originally written to be played on a sitar).

His solo on The Yardbirds’ 1966 hit Shapes Of Things was a further harbinger of the incredibly imaginative and revolutionary dimension he brought to his instrument. Inspired by the sitar sounds that The Beatles had recently introduced to the pop world, on Shapes Of Things Beck took off on a crazy, raga-type exposition, full of odd bends, “micro-sitar sounds” and atonal squalls of feedback that was unlike anything that had come before.

Pete Townshend had introduced the idea of harnessing the extraneous noises that could be coaxed from an overdriven guitar amp, on The Who’s single Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere, released in 1965. But it was Beck’s sortie on Shapes Of Things and the B-side, Mister You’re A Better Man Than I, that brought the idea into focus and put down a clear marker for what could – and soon would – be accomplished, at least six months before the unknown Jimi Hendrix arrived to play his first gigs in London.

Hendrix himself was an early subscriber to the Jeff Beck appreciation society. “Hendrix was fascinated by Jeff Beck’s playing,” recalled ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons, who toured with Hendrix in 1968. “He would put on one of his records and say to me: ‘Man, how do you think Jeff Beck is doing this?’”

It wasn’t just his groundbreaking technique that marked Beck out. A quiet and often reserved character off stage, he liked a drink but had little interest in drugs. “I didn’t like the idea of losing who I was. I had to stay sane. I watched everyone else fall down and it was so boring. Every night it was: ‘Who’s got the stuff?’” But he nevertheless brought a ton of attitude to the gig.

His status as a figurehead of the Swinging Sixties was underlined emphatically by his role in the film 1966 Blow Up, directed by Michelangelo Antonioni, in which The Yardbirds were featured playing on a set that was a replica of the Ricky-Tick club in Windsor. Beck was required to smash his guitar to pieces during Stroll On – an adaptation of the old rockabilly song The Train Kept A-Rollin’. He understandably refused to destroy his own guitar, a 1954 Gibson Les Paul.

“So they got Hofner to bring down these shitty guitars,” Beck later recalled. “I had this tea chest of twenty-five-pound joke guitars, and I went right through them with this Hofner rep watching at the side. He thought it was all great fun.”

According to The Yardbirds’ manager, Simon Napier-Bell, the experience of making the film gave Beck a taste for smashing up equipment on stage during the group’s ensuing US tour. “Gig after gig, he tottered round the stage, ramming the neck of his guitar through the speakers and crashing his feet into the delicate electrical controls. I was left a prisoner in my suite at the Chicago Hilton, phoning round America trying to find the location of every Marshall amp in the country and chartering planes to fly them to the next evening’s gig, only to be destroyed by another night’s bad-tempered Beck-ing.”

No doubt there was an element of exaggeration in Napier-Bell’s account. But maybe not that much. “Those amps never worked,” Beck later recalled. “I threw this amp out of the window once. It was in Phoenix or Tucson. The air-conditioning had broken. It was a hundred and forty degrees, unbearable heat, and the amp was crackling and then the heat just blew it up. It was a Vox, I think, and I just tossed the whole thing out the window. The power amp had a fixed cannon socket, so it wouldn’t pull out, and it was only that which prevented it from hitting this passer-by underneath. The amp was swinging above his head. God, we were tearaways.”

Beck left The Yardbirds midway through a US tour in 1966, pleading “inflamed brain, inflamed tonsils and an inflamed cock”, and soon embarked on a solo career.

After an unlikely string of hit singles, including Tallyman, Love Is Blue and the strangely unsinkable Hi Ho Silver Lining all masterminded by producer and pop Svengali Mickie Most, he formed his own group with Rod Stewart (vocals), Ronnie Wood (bass) and Mickey Waller (drums).

The debut album with this lineup, Truth (credited simply to Jeff Beck), released in August 1968, paved the way for the invention of the heavy rock genre, with tracks including You Shook Me, Rock My Plimsoul and Let Me Love You providing a virtual blueprint for the first Led Zeppelin album.

Such were the similarities in approach, Beck felt that with Zeppelin his old friend Page had borrowed over-freely from his stock of ideas. He vividly recalled the mixture of emotions he felt on hearing the first Led Zeppelin album, released the following year: “I was stunned, shocked, annoyed, flattered and just a bit miffed by the whole thing. But they had the lead singer that was going for the kill. But Rod… Maybe if I’d handled myself a bit better, kept Rod on the rails a bit. But things just happen. Every day is like a year back then, you don’t have much long-term view of things. You just fight for tomorrow all the time.”

After follow-up album Beck-Ola (1969), the Jeff Beck Group (Mk.1) disbanded with typically maladroit timing just before they were due to play at the Woodstock festival. Looking back in more recent times, Beck took a philosophical view. “I have to be grateful that I didn’t succeed, because you’re then lashed to the whipping post. I wouldn’t swap places with Jimmy [Page]. As much as I’d have loved to have been in Led Zeppelin and enjoyed all those amazing shows, in hindsight I’m much better off being a scout, going out in the field. That’s what I see myself as.

"Ironically, Page had an album called Outrider – and I was the outrider! I never, ever envisaged having massive success. And I’m glad I didn’t, otherwise people would be pointing at me in the street."

Beck put together a new line-up and recorded two interim albums with the Jeff Beck Group (Mk.2), the line-up being notable for the inclusion of keyboard player Max Middleton alongside Cozy Powell (drums), Clive Chaman (bass) and Bobby Tench (vocals/guitar). He also convened the short-lived supergroup Beck, Bogert & Appice (with the Vanilla Fudge rhythm section of bassist/vocalist Tim Bogert and drummer Carmine Appice) who released one self-titled studio album in 1973.

While the musicianship on these recordings was always of the highest order, there was the nagging sense of a supreme talent being employed in the service of less than stellar material. Then in 1975 Beck, together with Middleton, joined forces with George Martin, producer of The Beatles, and recorded Blow By Blow, an instrumental jazz/fusion album that set him apart from his superstar peers and pointed him on the path that would lead to the ultimate blooming of his artistry.

Fondly remembered for Beck’s spine-tingling interpretations of Stevie Wonder’s songs Cause We’ve Ended As Lovers and Thelonius – along with the Middleton composition Freeway Jam which quickly became one of Beck’s most reliable calling cards, Blow By Blow became his most successful album, reaching No.4 in the US and selling a million copies.

“That album was really a turning point,” Beck later recalled. “It gave me wings I never thought I had. It opened up the doors. It was red carpet, you know. Following it was difficult.” But follow it he did, with the equally remarkable and refined Wired (1976), again produced by George Martin, which marked the start of a liaison with keyboard player Jan Hammer along with Middleton (keyboards) and drummer Narada Michael Walden. Among the high points were the infectiously funky Come Dancing (written by Walden), an eerie Hammer composition Blue Wind, and a stunning version of the Charles Mingus standard Goodbye Pork Pie Hat given the full-screen Beck treatment.

“George Martin was probably the best producer I’ve had – the guy who could framework what I do without interfering,” Beck said, looking back on that period.

Beck concluded a trilogy of jazz fusion albums with There And Back, released in 1980, which remains one of his most underrated albums. With both Jan Hammer and Tony Hymas on keyboards, Mo Foster on bass and the superhuman Simon Phillips on drums, Beck took an uber-technical yet super-catchy melodic format to its outer limits.

The opening track, Star Cycle, a typically taut and edgy rumble written by Hammer, became the theme music for the zeitgeist-defining UK music TV show The Tube, while the supercharged, double-bass-drum-driven Space Boogie (written by Hymas and Phillips) took the virtuoso prowess of trailblazers like the Mahavishnu Orchestra and Billy Cobham into a thrilling new, accessible dimension.

Beck became something of a recluse – by rock star standards – during the 1980s and 1990s. While Clapton, Page and many of his other contemporaries were bestriding the stages in London and Philadelphia during Live Aid in 1986, Beck was content to follow events on a TV in the corner while he worked on one of his vintage hot rods in the garage of his estate near Tunbridge Wells.

“I didn’t want to go, because I hate large crowds,” he said afterwards. “I don’t mind playing to them, as long as you can get away quickly afterwards. But I wouldn’t have fitted in there anyway.”

Beck freely admitted at the time that his 1985 album Flash was recorded in response to record company pleas for “something we can sell”. Nile Rodgers was brought in as someone with a commercial ear to help with the production, and Beck was even persuaded to sing on a couple of tracks. The album was memorable for a reunion with Rod Stewart, who sang a heartfelt version of Curtis Mayfield’s People Get Ready, and for the track Escape, written by Jan Hammer, which won a Grammy for Best Rock Instrumental Performance. But regardless of the accolades, Beck’s heart didn’t seem altogether to be in it.

It was around this time Beck started to become known as an elite gun-for-hire, a role that he was happy to embrace but never took too seriously.

He contributed to Tina Turner’s breakthrough album Private Dancer (1984). “I played a pink Jackson guitar, and she sang Private Dancer once and Steel Claw once and that was it.” He worked on two of Mick Jagger’s solo albums, but dropped out of the band that Jagger was putting together to tour in Australia and Japan because “I didn’t want to play a load of Keith Richards licks”. He performed a supercharged slide solo on Jon Bon Jovi’s debut solo single Blaze Of Glory, a US No.1 hit in 1990. And he contributed to Roger Waters’ album Amused To Death (1992).

“I didn’t know what the hell the album was about,” Beck said. “[Waters] did explain it to me, but I wasn’t really listening. We just blazed away for about fifteen minutes, had a cup of coffee and went home. Forgot all about it. Next thing, it wound up as the lead track on the album.”

Beck’s blithe demeanour and seemingly offhand approach belied a steely determination to excel at everything he did, while never taking the accolades that were routinely heaped on him and his work too seriously. He was a connoisseur of musical styles and sounds, so much so that it seemed nothing was beyond his reach. Crazy Legs, an album he recorded in 1993 with the Big Town Playboys, was a spectacularly authentic homage to the guitarist Cliff Gallup who played with Gene Vincent on his first two albums, Bluejean Bop! (1956) and Gene Vincent And The Blue Caps (1957).

“Cliff Gallup’s guitar playing was absolutely phenomenal,” Beck said at the time. “His solos are so packed with dynamite on the wild numbers, and yet they’re full of knowledge and fluidity, melodic as hell.”

Beck’s command of the old-school finger-picking, rockabilly style employed by Gallup set him apart from the other rock guitar heroes of his – or indeed any – generation. As he continued to move through genres – from jazz rock to the more experimental sounds of electronica and 21st-century production methods – he never stopped improving, refining and exploring a playing style that gradually became little short of supernatural.

He continued to maintain a practising regime of anything between four and 10 hours daily. And somewhere along the line he ditched his plectrum completely and developed a way of micromanaging the pitch and tone of his Stratocaster by wrapping his fingers round the whammy bar while picking with his thumb. The technique gave him an uncanny ability to sculpt the shape and sound of the notes he was playing in an extraordinary style aptly summed up by guitarist Steve Lukather’s observation: “One note… and it was game over.”

By the time he reached the new millennium, Beck could acquit himself with distinction in virtually any musical environment. He was an incredible slide guitarist, as evidenced by his astonishing performance of the Nitin Sawhney composition Nadia captured on Beck’s album You Had It Coming (2000), in which he returned to his instrumental brief and extended it to encompass the realms of electronica, drum & bass, you name it.

He regularly got some of the finest musicians in the world to play in his bands. His live album with the Jan Hammer Group (1977) was an early landmark, while the trio comprising Tony Hymas (keyboards/bass) and Terry Bozzio (drums) with whom he toured and recorded the 1989 album Jeff Beck’s Guitar Shop were like ninja warriors.

But it was a run of dates at London club Ronnie Scott’s in 2007 that found him close to the absolute peak of his powers with one of the greatest and most sympatico line-ups he ever assembled: Jason Rebello (keyboards), Tal Wilkenfeld (bass) and Vinnie Colaiuta (drums). The sound and atmosphere in the venue on those nights was like nothing else – especially when Colaiuta and Beck sparred on the Billy Cobham tune Spectrum and the double-bass drum roller-coaster ride of Space Boogie. Beck’s wondrous interpretation of the Lennon/McCartney song A Day In The Life captured on the resulting album Live At Ronnie Scott’s (2008) won him yet another Grammy for Best Instrumental Rock Performance.

Beck’s 2010 album Emotion And Commotion (which netted him two more Grammys) found him stretching out in more unexpected directions (neo-classical, orchestral, soul) in the company of various singers including Joss Stone and Imelda May. Soon after it was released, May joined him at a special concert at the Iridium, New York in honour of guitar legend Les Paul. One of the songs they performed that night, a version of Remember (Walking In The Sand), a sixties hit by the ShangriLas, was a performance beyond compare.

“He inspired, supported and encouraged me with every whoop, cheer, gasp and tear when I sang with him,” May wrote on social media soon after the news of Beck’s death broke. “He was the genius in the room yet he made everyone else around him feel special. He was dedicated to making pure art. Every single note he played could kill me with its beauty. His light was so blindingly bright it already feels dark without him. The greatest guitarist that ever lived. The finest friend you could wish for. Thank you Jeff Beck.”

His old bandmate Ronnie Wood expressed similar sentiments: “Now Jeff has gone, I feel like one of my band of brothers has left this world, and I’m going to dearly miss him. I’m sending much sympathy to [his widow] Sandra, his family, and all who loved him. I want to thank him for all our early days together in the Jeff Beck Group, conquering America for the first time. Musically we were breaking all the rules, it was fantastic, groundbreaking rock’n’roll! Listen to the incredible track Plynth in his honour. Jeff, I will always love you. God bless.”

“Jeff you were the greatest, my man,” Rod Stewart said. “Thank you for everything.”