“The fans understood I was the price they had to pay to hear the band they loved, so they put up with me. It’s not like you’re joining the Sex Pistols”: Trevor Horn on fronting Yes – and how it later made 90125 possible

Six decades into his career, Trevor Horn has released a third album under his own name. Echoes – Ancient & Modern finds the musician and superproducer infuse a second collection of reimagined pop songs with his magic. He discusses reworking 80s anthems with Steve Hogarth and Robert Fripp, the Yes years and why he loves nothing more than making mischief.

“I always try to put two things together that don’t normally fit,” says Trevor Horn by way of trying to sum up a hugely diverse career as producer, musician and songwriter. That would explain the latest release to bear his name, which sees a number of curious marriages of artists and repertoire on a new album of covers.

Who else would commission Toyah Willcox and her prog-aristocrat husband Robert Fripp to tackle Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s Relax? Or persuade Rick Astley to take on Yes’s 1980s prog-pop chartbuster, Owner Of A Lonely Heart? Elsewhere, Steve Hogarth offers his reading of The Cars’ haunting, Live Aid-associated lament Drive, alongside numerous other curious match-ups.

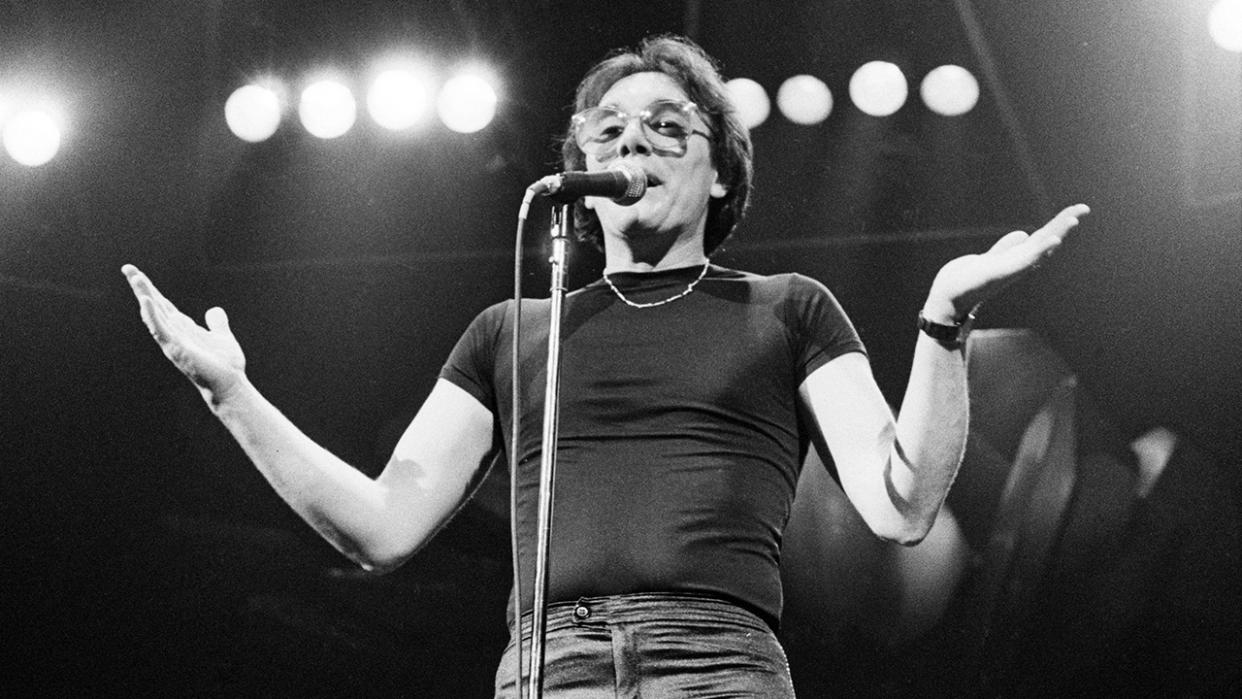

It’s a convenient jumping-off point from which to discuss a career that has been reliably unpredictable. He may be best-known to most as the producer who helped define the 80s with a string of ingeniously engineered pop releases – while wearing none-more-80s horn-rimmed specs – but he also played a notable cameo role in the history of prog as singer, then producer, of Yes.

The now 74-year-old’s new project is Echoes – Ancient & Modern, something of a follow-up to his 2019 set Trevor Horn Reimagines The Eighties, which also featured Hogarth among the line-up and also included a take on Owner, on that occasion with Horn on the mic. The impetus behind it was Deutsche Grammophon.

“We were talking about doing an acoustic record,” Horn explains. “But then I thought, ‘There’s plenty of other people that can make boring acoustic records, and I don’t need to join them.’ So I went back to do what I normally do, and although quite a few of the songs start out quite sparse, they then build up into something else.”

A case in point being his bossa nova-tinged reimagining of Joe Jackson’s jazz-inflected 1982 synthpop hit Steppin’ Out, with Horn’s old protégé Seal fronting a less urgent affair than the original. “The original is very fast,” Horn says. “A bit like: ‘You’ve just done a line of blow and you’re going out in New York.’ This new version is more like: ‘You just took some magic mushrooms and are going out in LA.’”

More radical overhauls ensue, such as Tori Amos’s repurposing of Kendrick Lamar’s Swimming Pools and Lady Blackbird’s loungey torch-song interpretation of Grace Jones’s Slave To The Rhythm. But it’s Toyah and Fripp’s camp strut through Relax that’s probably the most startling moment, the result of Horn’s approach of ‘if it ain’t broke, fix it anyway and see what happens.’ “At least it’s different, you know?” he says. “And I love Fripp’s guitar solo on it.”

I’m a connoisseur of voices and I think Steve Hogarth’s got a great one… one of the reasons Marillion are still going is because of him

As a long-time Yes fan, was he also a King Crimson devotee in his formative years? “I really liked In The Court Of The Crimson King, and I liked Starless And Bible Black and Red; I bought both of those. Then, probably like a lot of people, I lost track of them for a while. But then I saw them a couple of years ago and I’d never heard such expertly orchestrated chaos in my life!

“I’ve got a lot of respect for Robert Fripp,” he adds, “because when he goes out on the road with his band, he really looks after them. And that’s quite a rarity for artists to be so considerate to their musicians.”

And there we were, imagining Fripp to be a schoolmasterly presence conducting his charges with ruthless precision, the prog answer to James Brown, rapping his band’s knuckles for the slightest hint of a bum note... Horn grins. “You’re confusing him with Roger Waters.”

OK, then. The storied producer’s appreciation of Steve Hogarth, who fronts Drive on this album and tackled Joe Jackson’s It’s Different For Girls on Trevor Horn Reimagines The Eighties, has been a recent development. “My girlfriend’s a big Marillion fan, and I’ve grown to like them too,” he reveals. “I’m kind of a connoisseur of voices and I think Steve’s got a great one. He’s also a lovely fella. I think one of the reasons Marillion are still going is because of him.”

The presence of Owner Of A Lonely Heart on both those albums is a reflection of its prominent place on Horn’s CV. The version of the track sung by Rick Astley is a relatively faithful rendition of the song; the Yes original was a masterpiece of progressive pop – even if its birth was a traumatic one to say the least. By that time, though, Horn had earned the respect of the band, after having previously been a full member – frontman, in fact, for a faintly surreal spell.

Chris Squire had a way of talking. I thought, ‘Oh my God! Is he thick?’ … It was just a way he had of disarming people

After he and Geoff Downes shot to brief fame as the Buggles via their deathless 1979 chart-topper Video Killed The Radio Star, the manager they shared with Yes, Brian Lane, had the startling idea of the pair replacing Jon Anderson and Rick Wakeman after the latter two had walked out of Yes during early studio sessions for Drama in March 1980.

As it turned out, it was something of a youthful dream come true. A bass player by trade, Horn had long been in awe of Chris Squire in particular. “I thought he came up with more original bass lines than any other player. The first time I met him was pretty memorable. He was so big, like 6’5” or something. And he had a way of talking, kiiiind of liiike thiiis... and I thought, ‘Oh my God! Is he thick?’ Of course, I was totally wrong. It was just a way he had of disarming people.”

Although the newcomer held his own creatively in the band, he always felt daunted by stepping up to the same mic as his predecessor. “Jon Anderson’s a hell of a singer, you know? He must have a range beyond mine. Still, it was one of the great experiences of my life. And what a moment, being in a rehearsal room and listening to Alan White, Chris Squire and Steve Howe play close up. I never heard anything like it. I mean, the intensity of it...”

Contrary to some accounts (Rick Wakeman once quoted Chris Squire as having told him it was “an absolute nightmare from start to finish” due to their fans’ adverse reactions), Horn doesn’t remember receiving much flak. “I think people were reasonably accepting. I think they understood that I was the price that they had to pay, you know, to hear the band they loved. So they put up with me. I mean, they’re a pretty civilised lot, Yes fans. It’s not like you’re joining the Sex Pistols!”

Yes splintered further after the tour, with Downes and Howe leaving to form Asia. Meanwhile, Horn met the increasing demand for his services as an innovative producer, helping to sculpt post-modern pop par excellence with Dollar and ABC while also mentoring a new Liverpool band called Frankie Goes To Hollywood, signed to his own label ZTT.

At the time I was probably one of the most successful producers in the world… I would never have worked with Yes again if I hadn’t loved them

Around the same time, though, he was working with the band renamed Cinema by Squire and White, who had now hooked up with South African guitarist Trevor Rabin and original Yes keyboard player Tony Kaye. And when Anderson returned to the fold and they readopted the Yes name, Horn retained a significant creative input.

“I would never have been able to have the input I had as producer on 90125 if I hadn’t previously been in the band,” he says now. “They kept trying not to do Owner Of A Lonely Heart. One day, when I got to the studio, there was a deputation waiting for me saying, ‘We’ve all decided that we’re not doing it.’

“I got on my hands and knees on the floor, pulled at everybody’s trouser legs and made a noise and shouted, ‘Pleeease pleeease, please have one more go. Let me programme the drums! It’s got to be simple. It’s just got to go, “Boom, chick, boom boom, boom boom” – it can’t go “doo de doop dook doop, doo dook, chick chick doop boof...”’ like everything we’d been trying.

“I made such a fuss, saying, ‘I only took this album because you said you’d do this single!’ They were so embarrassed – and maybe amused at the same time – by my display that eventually, they grudgingly agreed to have one more go. This time, programming it. I could never have done that if I hadn’t been in the band.

“At the time I took that job on I was probably one of the most successful producers in the world. And I would never have worked with Yes again if I hadn’t loved them, because they were a pain in the neck! But, when I listen to that record now, I am so glad I did it because they were also fuckin’ brilliant, you know?

“Alan, the drummer, all that stuff he did with the samples in the middle of Owner Of A Lonely Heart. A talented musician is a talented musician, it doesn’t matter if he’s on a sampler or a fucking banjo. And they were great, Chris and Alan. Trevor Rabin was no slouch either; he played all the keyboards and all the guitars.”

That wasn’t the end of the conflict surrounding that landmark single – Horn walked out on the project for around six weeks in a stand-off over a snare sound in the final mix, until legendary producer Ahmet Ertegun stepped in on his side and demanded the band reinstate Horn’s version.

You have total control in the studio; live, it’s a car crash and when it actually works it feels kind of like a minor miracle

But that’s a story for another day. Fast-forward to the present, and while we await the verdict of Horn’s former bandmates on Rick Astley’s version of Owner, another guest from the prog world who is set to feature on a bonus track on forthcoming expanded editions of the album is King Crimson’s Jakko Jakszyk. He takes on Visage’s 1980 synthpop noir classic Fade To Grey. “We changed it quite drastically,” is all Horn will say about that one, joking, “because the original was quite sketchy.”

Meanwhile, the musician in Trevor Horn still keeps his hand in. The band he formed as Producers in 2006 with Lol Creme and initially Chris Braide, which made 2012’s very tidy prog pop album Made In Basing Street, is now The Trevor Horn Band, and Horn reports that the LP is to be reissued at some point this year. “We’re talking about maybe doing a couple of shows together. I’ve got to try and persuade Lol...”

He has also toured recently with tribute act Dire Straits Legacy, and admits that being onstage is a very different thrill to the buzz he gets from his studio work. “Performing is like instant gratification,” he says. “You have total control in the studio; live, it’s a car crash and when it actually works it feels kind of like a minor miracle.”

He even opened for Seal recently alongside erstwhile Yes colleague Geoff Downes as Buggles, and in their set was Owner Of A Lonely Heart and Horn’s Art Of Noise hit Close To The Edit. That title’s reference to his former band was probably lost on pop-pickers in the 80s. But that’s Horn all over.

“I like to make a bit of mischief sometimes,” he says with a grin. You can take the boy out of prog.